January 10, 2023

The early 1920s were the peak of the Nisei baby boom and, according to War Relocation Authority records, the year 1923 saw the second largest number of Nisei (and undoubtedly a handful of Sansei) births in any year. In the 2023 edition of our Nisei Notables series, Densho Content Director Brian Niiya introduces us to a few of the remarkable Nisei who were born one hundred years ago.

Having just turned eighteen as World War II broke out, the war loomed large in the lives of each of this year’s Nisei Notables and, in many cases, shaped the contributions they made to our collective history. (Though I use the term “Nisei” here broadly, note that some of these individuals may not technically be Nisei, e.g. Mitsuye Yamada, who was born in Japan, but considers herself to be Nisei.)

Artists and Writers

Several notable artists and writers are among this group. John Okada was a librarian and technical and advertising writer by day who wrote the legendary novel No No Boy on the side. Received indifferently by the Nikkei community upon its 1957 release, it did not sell well and was largely forgotten until the 1970s, when a new generation of scholars and activists rediscovered it. It has since become a classic of Asian American literature and a staple of Asian American Studies courses. A recent anthology and biography edited by Frank Abe, Greg Robinson, and Floyd Cheung has filled out Okada’s story and other writings. He died young, at age 47, in 1971.

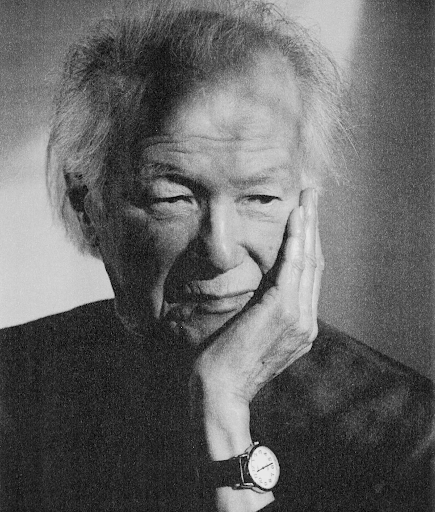

In contrast, Mitsuye Yamada has led a particularly long life as she prepares to celebrate her 100th birthday this year.

The acclaimed poet, teacher and activist—who is the mother-in-law of Densho’s Oral History Program Manager/Grants Manager Virginia Yamada—is technically an Issei, since she was born in Japan to an Issei mother who happened to be in Japan at the time of her birth, but had a quintessentially Nisei life. Shaped by her father’s internment and her family’s subsequent incarceration at Puyallup and Minidoka, she eventually embarked on a teaching career while also pursuing her own writing and activism, her poetry and essays reflecting on her family’s wartime incarceration, feminism, social justice and many other topics. She and her brother were the subjects of Diane C. Fujino’s recent book Nisei Radicals: The Feminist Poetics and Transformative Ministry of Mitsuye Yamada & Michael Yasutake.

Like Okada, Milton Murayama published an early novel that illuminated little known aspects of the Japanese American experience that was later rediscovered by scholars and activists and has since become a classic. First published in 1959, All I Asking for Is My Body was set on Hawai`i sugar plantations, capturing Issei and Nisei life there and the language and mores of the islands. While working as a US customs agent—where he was a friend and colleague of one of my uncles—he wrote several plays and novels that continued to shed light on the Nisei experience in Hawai`i.

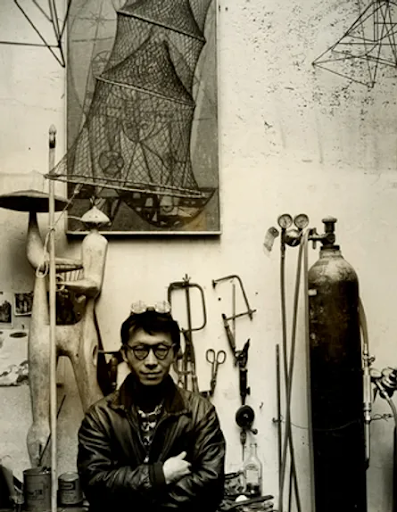

Three notable Nisei male visual artists were also born in 1923. Tadashi Sato was part of a cohort of Nisei artists from Hawai`i—many of whom, like Sato, were also World War II veterans—who studied in New York in the early postwar years and were part of the abstract expressionist movement of the time. Sato is best known for his mosaic work “Aquarius,” which is the courtyard of the Hawai`i State Capitol building. Kibei painter Taneyuki Dan Harada studied art at the Tanforan and Topaz Art Schools and later pursued an art career after the war. He is perhaps best known for his oil paintings that depict his wartime incarceration. Nisei artist and World War II veteran Shinkichi Tajiri took the extraordinary step of leaving the United States in 1948, embittered by his and his family’s wartime incarceration and the continuing discrimination Nikkei faced after the war. Eventually settling in the Netherlands, he became well known for his sculptures that include one located in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles and one in Bruyéres, France, the latter a tribute to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team that had liberated that city.

In the performing arts arena, dancer Michiko Iseri parlayed her prewar Japanese dance training into a postwar career that included being part of the original Broadway cast of Rogers & Hammerstein’s The King and I alongside fellow Nisei dancer Yuriko Amemiya Kikuchi. She appeared in the entire three year run of the show as well as being part of the touring company in 1954–55.

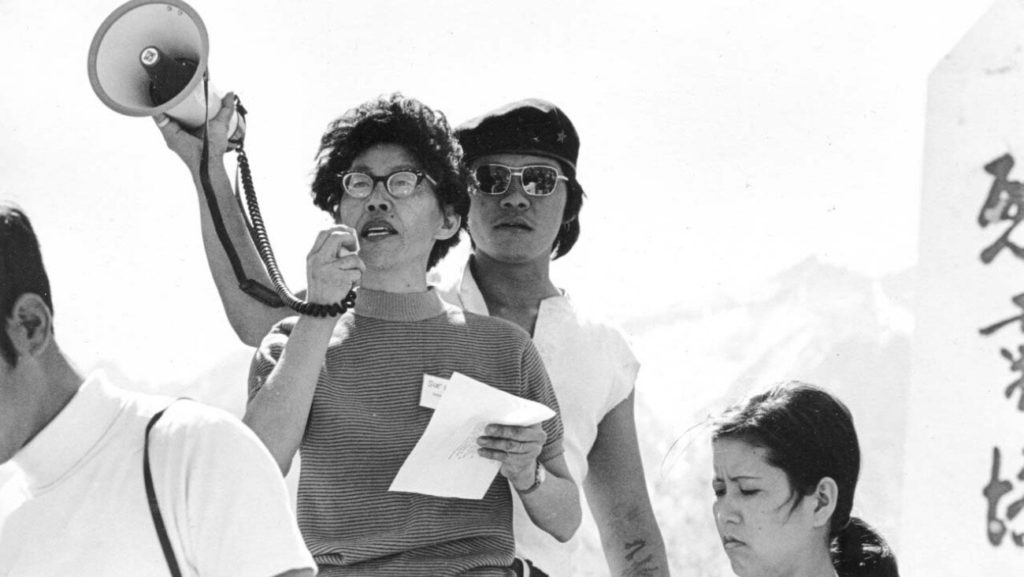

Activists

Several notable activists were also born in 1923. Though probably best known for her role in starting the Manzanar Pilgrimage—which led to the formation of Manzanar Committee and the larger phenomenon of camp pilgrimages in general—Sue Kunitomi Embrey‘s political involvement goes back to the 1950s when she was a core member of the Nisei Progressives. She remained active in labor and women’s issues throughout her life.

After her incarceration at Poston, Nikki Sawada Bridges Flynn worked as a legal secretary while becoming active with the AFL-CIO and the Berkeley Interracial Committee. She later married labor leader Harry Bridges, challenging bans on interracial marriage in the process. She later became an acclaimed writer and essayist and was active in the Redress Movement.

Cherry Kinoshita and William Marutani were other key figures in the Redress Movement. Kinoshita was active with the Seattle JACL, becoming its president and also serving on the national JACL board. She also played a key role in the push for reparations for Japanese American Washington state employees who had been fired during World War II. Marutani was the lone Japanese American member of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Active in the JACL before that, he was one of that organization’s most ardent supporters of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, even going to Louisiana in 1965 as a volunteer lawyer to help enforce the Voting Rights Act. He was appointed a judge of the Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia and after his retirement served as the board chairman of the National Japanese American Memorial Foundation.

Yosh Kuromiya was one of the Nisei draft resisters at Heart Mountain and was a key figure in reviving the story of the resisters in the 1980s and 1990s and beyond. He was also a successful landscape architect in Southern California. His memoir, Beyond the Betrayal: The Memoir of a World War II Japanese American Draft Resister of Conscience, remains the only memoir by a Nisei draft resister.

Veterans

In addition to the various World War II veterans already mentioned above, there are a few others of note. Yoshiaki Fujitani was a student at the University of Hawai`i when war broke out and was among the Nisei who were activated as part of the Hawai`i Territorial Guard and who later joined the Varsity Victory Volunteers when the Nisei were discharged from the HTG. He later made the difficult decision to volunteer for the Military Intelligence Service despite the fact that his father, an Issei Buddhist minister, had been arrested and interned. After his military service, he became an ordained Jōdo Shinshū priest and was later elected bishop of the statewide Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawai`i in 1975. He remained active in Buddhist education after his retirement and was also part of the Hawaii Nikkei History Editorial Board that published several books on the experiences of Nisei veterans in Hawai`i.

Lawson Sakai served in the 442nd and took part in the rescue of the “Lost Battalion,” where he was badly wounded. He later was a key figure in organizing veterans reunions and other activities and was a willing and lively spokesman for the Nisei veterans in his later years. He is featured in “The Interactive StoryFile of Lawson Iichiro Sakai” at the Japanese American National Museum, an interactive exhibit that allows visitors to have a conversation with Sakai.

Frank H. Ono was one of the twenty members of the 442nd or 100th who was awarded the Medal of Honor, the country’s highest military honor, in 2000. Born to an Issei father and a white mother in Colorado, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions during a July 4, 1944 battle near Castellina, Italy. He spent most of life in Indiana and died there at age fifty-six in 1980.

Chroniclers

Paul Takagi and his family were among the four hundred or so Nikkei from the Florin/Elk Grove area who were sent to Manzanar, where he worked alongside Sue Kunitomi on the Manzanar Free Press. After serving in the 442nd and MIS, he became a renowned criminologist and activist at UC Berkeley. His work, and that of his colleagues, so angered Governor Ronald Reagan and state officials that the state eliminated the School of Criminology in 1974. He went on to become a key figure in the founding of Asian American Studies and was active in the campaign to repeal Title II of the Emergency Detention Act, a precursor to the Redress Movement.

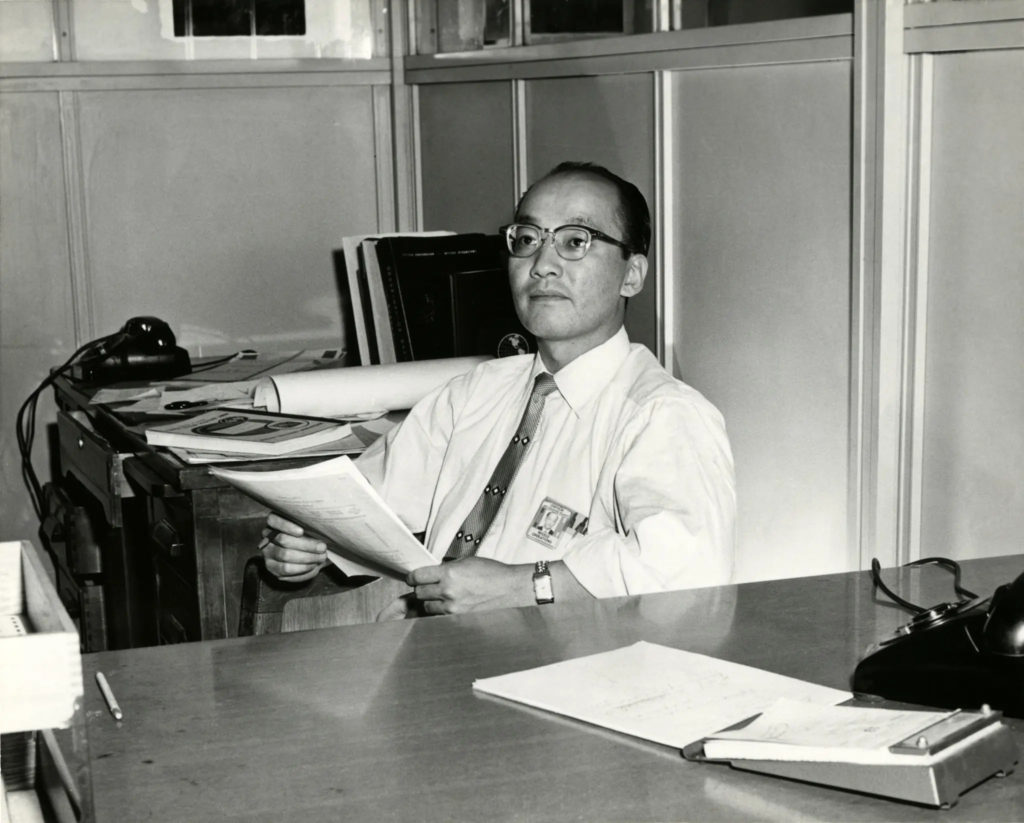

We end this year’s roundup with photographer Hikaru Iwasaki. He is best known in mainstream circles as a news photographer whose work has appeared in such publications as Time, LIFE, and Sports Illustrated. But he began his career as a young photographer for the WRA Photographic Section (WRAPS). First hired as a darkroom technician at age nineteen while incarcerated at the Heart Mountain, Wyoming camp, Iwasaki became the third full-time WRAPS photographer a year or so later, and the first Japanese American. He spent much of the next two years taking the “happy” photos of Japanese American resettlement in places outside the West Coast restricted zone that you have no doubt seen. Iwasaki settled in the Denver area after the war and years later, Lane Hirabayashi, then teaching at the University of Colorado, tracked him down. The pair (along with Kenichiro Shimada) collaborated on a 2009 book, Japanese American Resettlement Through the Lens: Hikaru Carl Iwasaki and the WRA’s Photographic Section, 1943–1945, that reevaluates the work of Iwasaki and the other WRA photographers.

Reactions from scholars, students, and knowledgeable community members have ranged from those who view the photos as propaganda and Iwasaki as “selling out” his community, while others see the larger mission the photos contributed to of getting Japanese Americans out of the concentration camps as worthwhile. But I think we all agree that the photos are valuable as documentation of a historic event if viewed in the proper context.

As we mark the centennial anniversary of so many of our Nisei elders and ancestors, our country is as divided as ever. Let’s take a cue from Iwasaki’s legacy as we continue seeking the right context for viewing the sometimes bewildering events that are happening all around us.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

Sources:

Most of the information in this piece comes from relevant Densho Encyclopedia articles on that person. On John Okada, see Frank Abe, Greg Robinson, and Floyd Cheung, John Okada: The Life and Rediscovered Work of the Author of No-No Boy (University of Washington Press, 2018); on Shinkichi Tajiri, see Greg Robinson, “Shinkichi Tajiri and the Paradoxes of Japanese Identity” in Helen Westgeest, ed. Shinkichi Tajiri’s Universal Paradoxes (Leiden University Press, 2015) and shorter version of that essay on Discover Nikkei, Sept. 17, 2019; on Michiko Iseri, see Dyke Miyagawa, “Two Misses in a Hit Musical,” Scene, Dec. 1951, 8, Bill Hosokawa, “From the Frying Pan: Sunshine Makes Her Itch,” Pacific Citizen, Sept. 10, 1954, 12, and Hana C. Maruyama, “Getting to Know You: Broadway Meets Heart Mountain,” The Margins (Asian American Writers Workshop), Oct. 15, 2015; on Yosh Kuromiya, see Yoshito Kurumiya, Beyond the Betrayal: The Memoir of a World War II Japanese American Draft Resister, ed. Arthur A. Hansen (University Press of Colorado, 2021); and on Lawson Sakai, see his 2019 Densho interview by Patricia Wakida and “The Interactive StoryFile of Lawson Iichiro Sakai,” Japanese American National Museum; on Frank H. Ono, see 1930 Census at https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:X4B4-NZ3, 1950 Census at https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6XLH-XR8Z; and Find A Grave Index, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVVQ-M3FJ.

Want more Nisei Notables? Read Brian’s previous roundups from 2022 and 2021.

[Header: A child’s birthday party in June 1956. Courtesy of the Okano Family Collection.]