January 11, 2022

One hundred years ago, we were in the midst of a Nisei baby boom, and thus, there are many Nisei whose 100th birthdays deserve some special celebration in 2022. These are people who were around twenty years old when the U.S. entered World War II, and the war years played a large role in each of their lives. To begin the new year, let’s look at a few of these Nisei notables.

Nisei Veterans Stories

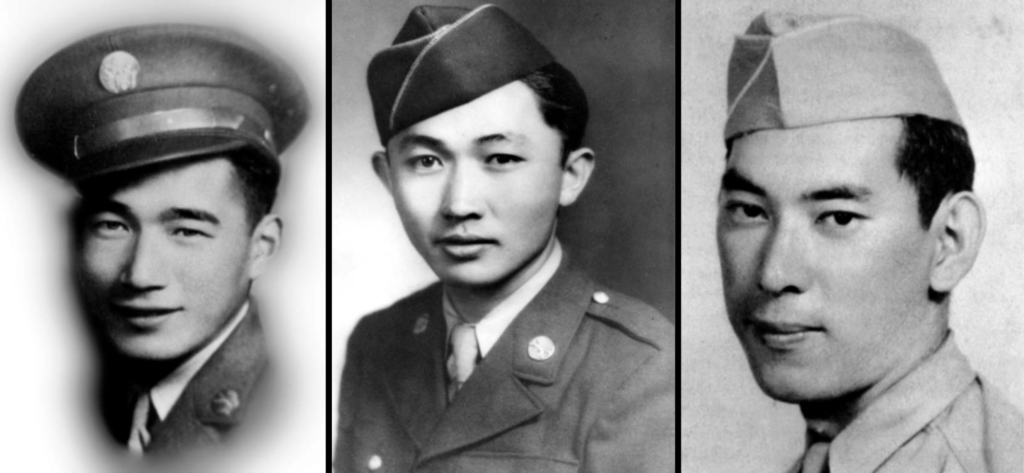

A great many of the Nisei who served in World War II were born in 1922, including four of the twenty who were awarded the Medal of Honor, the country’s highest military honor. Tragically, each of the four were killed on European battlefields in the course of the actions resulting in their honor.

The best known of the four is undoubtedly Sadao Munemori of Glendale, California, the only Japanese American to be awarded the medal at the time. He died in Italy, on April 5, 1945, when he smothered a grenade with his body, saving two other men. Because of his unique status as the only Japanese American WWII Medal of Honor awardee for over fifty years, his story has been told many times in recounting the exploits of the Nisei soldiers. A troop ship, a highway interchange in Los Angeles, and a building at the U.S. Reserve Complex in West Los Angeles are all named after him.

The other three were among the group who had their awards upgraded in 2000. William Nakamura of Seattle was incarcerated with his family at Minidoka concentration camp, from where he volunteered for the army when Nisei eligibility was restored in 1943. He was killed on July 4, 1944, near Castellina, Italy. Years later, a Seattle courthouse—the one in which Gordon Hirabayashi had been convicted of disobeying curfew orders—was named after him.

Kiyoshi Muranaga of Gardena, California was incarcerated with his family at the Amache, Colorado, concentration camp when he volunteered for the army. (It is notable that Nakamura and Muranaga were in the two camps that had by far the largest number of volunteers for the army, indicating a much more positive attitude in the community towards military service than in the other WRA camps.) Muranaga was killed near Suvereto, Italy, on June 26, 1944 as part of the mortar squad of Company F of the 442nd. As with the notorious case of Hood River, Oregon, the Gardena VFW chapter banned Japanese American soldiers from its service plaque, and Muranaga’s name was thus left off despite his heroism.

Robert T. Kuroda was the seventh of nine children of an Aiea, Hawai`i family that ran a well-known service station. Kuroda had graduated from vocational school as an electrician, but was rebuffed by the navy, which refused to hire Japanese Americans, when he tried to get a job at Pearl Harbor. When Nisei eligibility to serve was restored, Kuroda was among those who volunteered for the 442nd. He was killed on October 20, 1944, near Bruyères, France. In 2003, the SSGT Robert T. Kuroda was dedicated; ironically, it was to be based in Pearl Harbor. The Kuroda family’s auto repair shop remains in operation today.

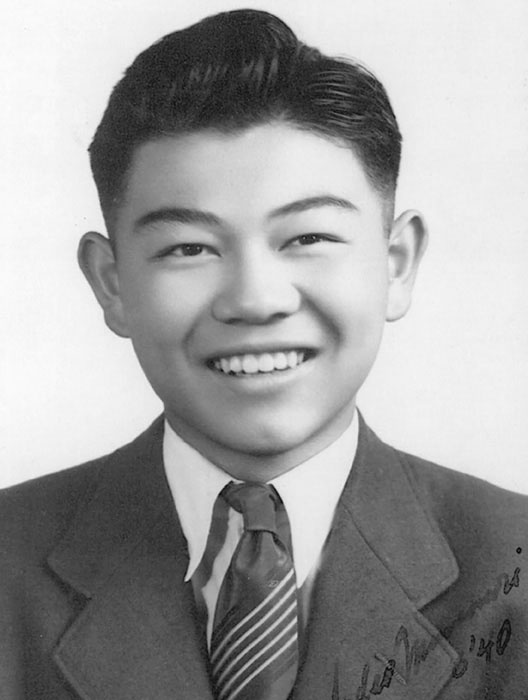

Though his story is not as well remembered today, Frank Shigemura’s was one of the most publicized Nisei veterans stories in the 1950s. From Seattle, Shigemura had graduated from Broadway High and had just started at the University of Washington in the fall of 1941. Forcibly removed to Puyallup and Minidoka with his parents, he was among the first Nisei to leave camp for college with the assistance of the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, departing in October 1942 for Carleton College in Minnesota. He enlisted when Nisei eligibility was restored the next spring, joining the 442nd. Tragically, he was among the Nisei killed in the rescue of the Lost Battalion in October 1944. After Carleton published a booklet honoring Shigemura and other students who had died in military service, his parents began sending regular donations to the school which the school used to set up a scholarship in his name. Despite their modest income the donations continued, to the point where College President Lawrence M. Gould had to gently tell them to stop the donations when he saw the poverty they lived in. The story was featured in Reader’s Digest in 1950 and on the TV show We, the People a year later, as well in other outlets. In 2010, Carleton Professor Fred Hagstrom produced an artist’s book on the story, reviving interest in it. The scholarship continues to this day.

Legal and Political Leaders

Other Nisei veterans who survived the war built substantial legacies in the postwar world, including two of the stars of Daniel James Brown’s book, Facing the Mountain, Katsugo Miho and George Oiye. Born and raised on Maui, Miho enlisted for the 442nd in the spring of 1943 and eventually became an artilleryman in the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion. After completing his law degree at George Washington University, he embarked on a legal and political career back in Honolulu that saw him elected to the state legislature and later appointed as a family court judge. He also became well known locally for promotion of sumo, serving as an advisor to local youth who went on to groundbreaking careers in sumo in Japan. Oiye was born and raised in Montana and also ended up in the 522nd after enlisting in the spring of 1943. He later became an engineer in California and became known for the many photographs he took documenting his wartime experiences that are now in the collection of the Japanese American National Museum.

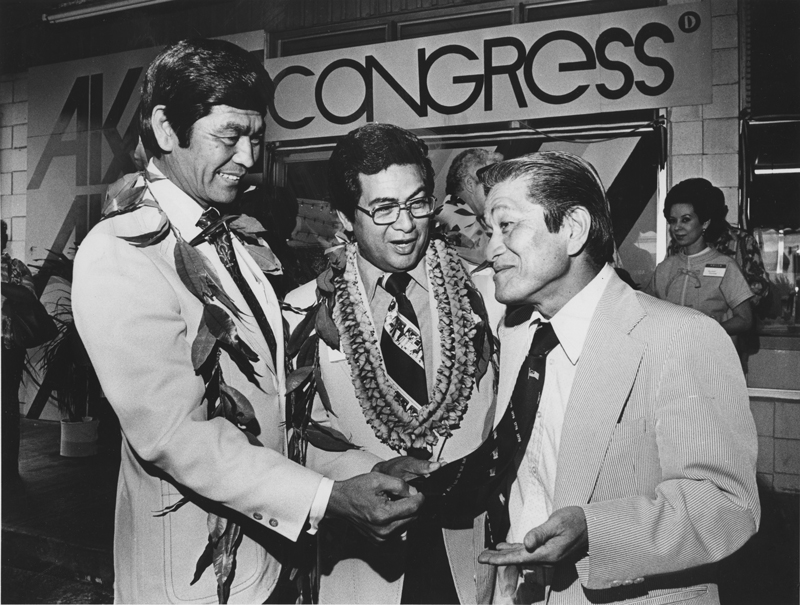

Yoshimi Hayashi was among the Hawai`i Nisei who formed the Varsity Victory Volunteers when they were kicked out of the army, and he went on to serve in the Military Intelligence Service in the Philippines and in occupation Japan. Attending law school at George Washington University, where he followed other Nisei veterans from Hawai`i, including Katsugo Miho and his older brother Katsuro as well as Daniel Inouye. Hayashi returned to Hawai`i and eventually became the first Japanese American U.S. Attorney and later served on the Hawai`i State Supreme Court.

Other Nisei born in 1922 who made their mark in politics included Nelson Doi and Nao Takasugi. The iconoclastic Doi was born and raised on the Big Island of Hawai`i, and after serving as a state senator and judge, won election as the lieutenant governor of Hawai`i in 1974. Born and raised in Oxnard, California, Takasugi was incarcerated at the Tulare Assembly Center and Gila River concentration camp with his family, leaving the latter to college back east in February 1943. After finishing an MBA at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, he returned home to run the family grocery store for decades. He entered local politics in the 1970s and served as mayor of Oxnard for ten years, then election to the California State Assembly in the 1990s.

Artists, Writers & Musicians

Several Nikkei artists born in 1922 also made their mark. Harry Yoshizumi was born and raised in Watsonville, California and became known for his watercolor paintings depicting scenes from his incarceration at Poston, where he studied art. He gained fame for his modernist paintings after the war in New York and the San Francisco Bay Area.

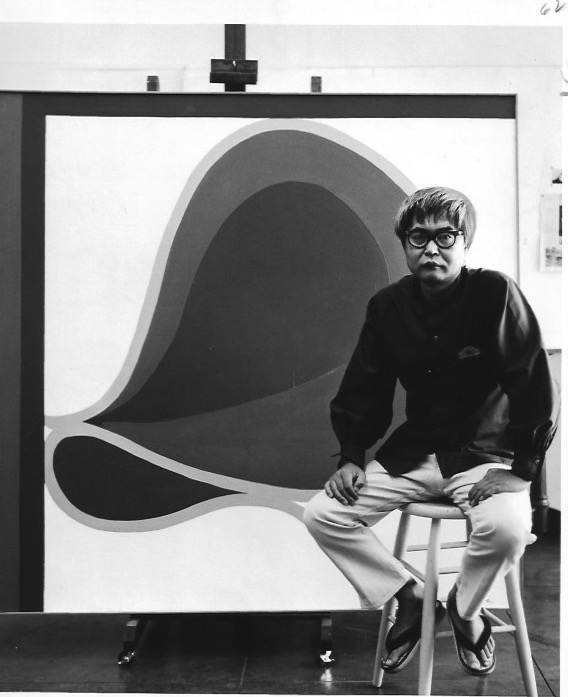

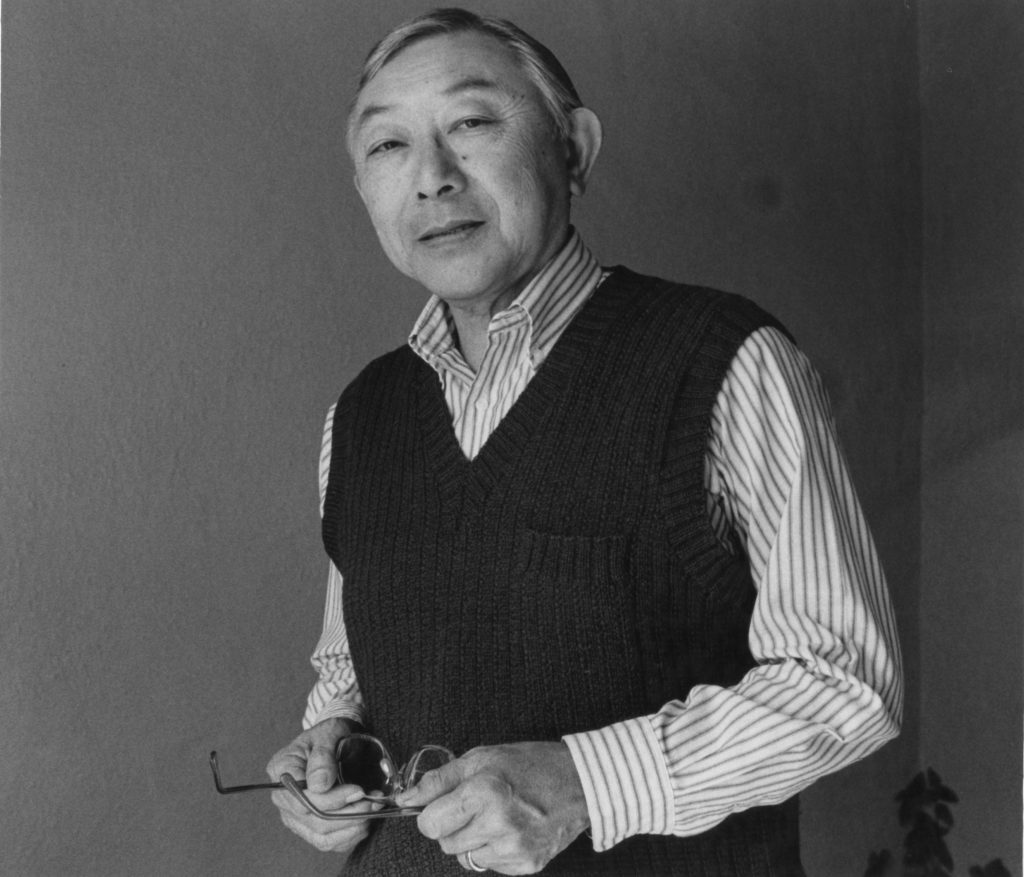

Kibei artists Matsumi Mike Kanemitsu and Margie Masako “Koho” Yamamoto are both known for their postwar work that incorporates Japanese ink techniques into modernist abstraction, and both were based in New York for a time. Yamamoto—who attended the well-known art schools at Tanforan and Topaz—has seen her fame grow in her 90s, as she became a fashion icon while continuing to run a school of Japanese calligraphy. She is still going strong as she approaches her 100th birthday.

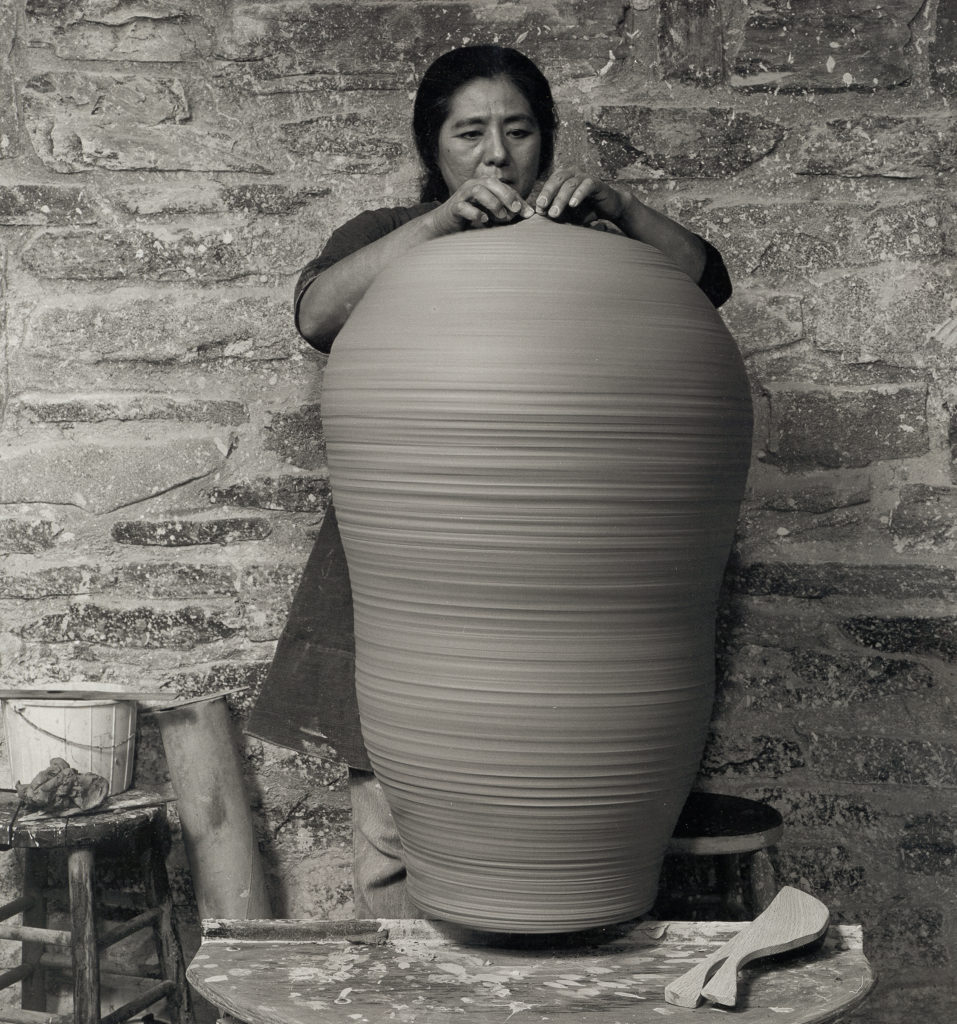

Toshiko Takaezu’s life was a remarkable journey that saw her go from the Big Island sugar plantation town of Pepeekeo to one of the world’s most acclaimed ceramic artists, known for her large closed form pieces that helped transform ceramics from craft to fine art in the mid-twentieth century. Though based in New Jersey for most of her adult life, where she was also a beloved teacher and mentor, most notably at Princeton University, she retained close ties to Hawai`i and taught regular classes at the Richards YMCA in Honolulu.

Highlighting the literary and performing arts arena is Hiroshi Kashiwagi, a beloved playwright whose plays were among the first to explore the impact of the wartime incarceration and its aftermath. Two notable Nisei musicians, Tak Shindo and George Yoshida, were also born in 1922. Shindo taught ethnomusicology at Cal State Los Angeles, recorded several albums that incorporated Asian instruments into Western big-band arrangements, and composed music for Asian themed movies and TV shows. He also produced a pioneering film on the incarceration, Encounter with the Past: American Japanese Internment in World War II (1980). A saxophonist in the Poston dance band the Music Makers, Yoshida was a teacher in Berkeley after the war while also playing in a variety of bands and later authoring a history of Japanese Americans in popular music, Reminiscing in Swing Time: Japanese Americans and American Popular Music, 1925–1960 (1997).

Community Activists and Public Figures

Among the many Nisei who played significant roles in their communities were Rev. Lloyd Wake and Marjorie Matsushita Sperling. After his wartime incarceration at Poston, the former left camp to attend college at Asbury College in Kentucky before becoming a prominent Bay Area Methodist minister at Pine United Methodist Church and Glide Memorial Methodist Church. A human rights activist throughout his life, Wake also supported the Third World Liberation Front Strike at San Francisco State University in the 60s, led efforts to secure a fair trial for Wendy Yoshimura in the 70s, and was active in the redress movement in the 80s. Sperling was from the Yakima Valley in Washington State and was incarcerated at the Portland Assembly Center and Heart Mountain. Like Wake, she left camp to go college—Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota, in her case—before embarking on a career in recreation and volunteer services. Later in her life, she was a key figure in the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation and played an important role in the acquisition of the land that camp once sat on.

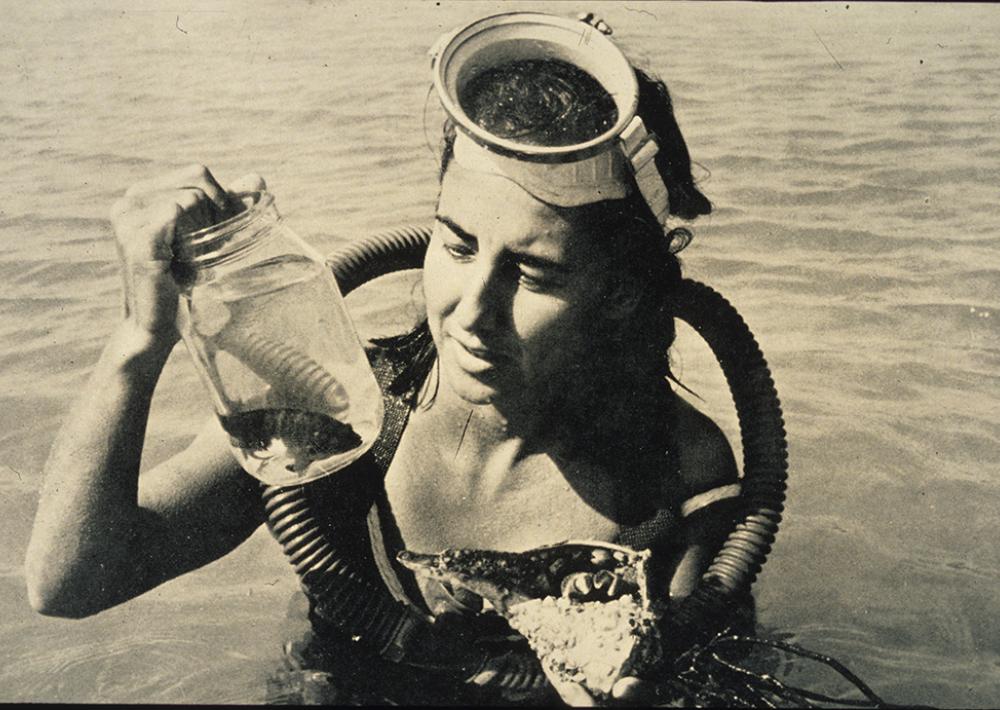

We’ll close this brief summary of notable 100th birthdays with the unusual Nisei story of Eugenie Clark. Born and raised in New York City, the daughter of a white father and Issei mother, she avoided any direct connection to the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans, though she certainly experienced the racism of growing up non-white and Asian American. Inspired by a childhood visit to a local aquarium, she developed a love for the sea and its biology and became a marine biologist at the University of Maryland and a well-known public figure. Her two memoirs—Lady with a Spear (1953) and The Lady and the Sharks (1969)—along with articles in National Geographic, raised public awareness about marine life and conservation. As someone who literally swam among sharks to great success and acclaim, she seems like a person we can all aspire to be in the shark filled waters of 2022.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

[Header: A group of friends posing for a photo. Courtesy of the Milton and Molly (Kageyama) Maeda Collection.]