June 29, 2020

Guest post by Sara Onitsuka

The last few weeks of protest, sparked by the murder of George Floyd and rising out of 400+ years of slavery, genocide, and other white supremacist and anti-Black violence, have shattered previous ideas of what we thought was possible. More than a dozen cities across the country have proposed to cut some funding from police, and Minneapolis, where the protests began and continue with strength, has taken it a step further by voting to disband the police department. This is a time where we have been called to urgently continue learning and expanding our own political understanding and practices.

One of the most exciting developments is that police abolition has entered mainstream discourse. Calls to defund and disband police departments are ringing in every city, and platforms such as The New York Times have published articles urging that we “literally abolish the police.” It is important to name that, as surprising as it feels to some, the push for abolition is not a spontaneous or nascent thing. We are having these conversations thanks to decades of work by Black abolitionist organizers—many of them Black women such as Angela Davis, Mariame Kaba, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Rachel Herzing, and more—who have studied, imagined, organized, and created alternatives to bring us ever closer to a liberated future.

As this moment awakens the potential for abolition in mainstream consciousness, I have been reflecting on my own community and family history. As a yonsei Japanese American with three grandparents who were incarcerated during World War II, I have come to realize that being an abolitionist honors my own family history. I believe that the only way I will ever get justice for my grandparents and all other members of my community who were wronged, is to abolish police and prisons and end the culture of policing that permeates this society.

I want to talk about what abolitionists mean when we call for abolition, what we mean when we describe “the culture of policing,” and why this is important for all Japanese Americans.

What is the Prison Industrial Complex?

I am noticing that mainstream discourse focuses a lot on police abolition, and less on prison abolition. But when we talk about abolition, it includes both police and prisons, and the whole industries and institutions that support them. This is known as the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC), described by the organization Critical Resistance as “the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems.” In other words, the PIC includes the whole criminal justice system, from arrest to incarceration to parole. It includes the corporations that use prison labor, provide weapons and technology to police and prison guards, and even the ones that operate prison food services. It is truly a ‘complex’—a complicated ecosystem of sorts that is entangled into our everyday lives in terrifying and easily overlooked ways.

The PIC continues to exist because we have internalized and legitimized the idea that we need policing to keep us safe, i.e. the culture of policing. Angela Davis said, “The prison is considered so natural and so normal that it is extremely hard to imagine life without them.” So when we talk about PIC abolition, it is not just abolishing external structures such as police forces or physical prison buildings. It is also about ending the culture of policing and building a society that cares for its people.

We have been made to believe that there really are “good” and “bad” people, and that “bad” people must be caught by the police and sent to prison. We believe that “bad” people deserve to be punished, and that locking them away, out of sight, will make our communities safer.

This could not be further from the truth. I will not go into detail here, because there are many articles and books that have explained already how policing and incarcerating people does not make us safer, and how it is neither accountability nor justice. The PIC continues to fail us and puts marginalized communities—especially Black, Indigenous, and undocumented communities—in greater danger.

How does this relate to Japanese American history?

As Japanese Americans, we know personally and painfully how a community can be unjustly demonized, criminalized, and sent away to suffer, as punishment for simply existing. The government sent us far away into rural areas, and in the cases of Gila River and Poston, against the wishes of the Indigenous people whose land they were occupying. The Tule Lake Concentration Camp, where my grandfather on my mother’s side was incarcerated, had a jail built within the camp to contain the people who were deemed even worse than the rest of those already imprisoned. When my mom and I visited Tule Lake during the Tule Lake Pilgrimage in 2018, we were able to walk through the jail, which was a little dilapidated but still standing. I cannot begin to describe how much pain was there—it seeped out of the ground and the carvings in the walls. It is almost funny, in a sick way, how they built another jail within a jail. One was not enough, apparently. That is how embedded the culture of policing is in our society.

During this era of anti-Japanese suspicion, Japanese Americans were seen as dangerous and threatening to the US—again invoking the narrative of good versus bad people, or law-abiding citizens versus criminals. There were many specific examples of the ways Japanese Americans were not only policed, but deeply harmed throughout the whole process of the so-called “justice system,” all branches of the prison industrial complex. The FBI arrests of over 8,000 Issei after Pearl Harbor is one such example.

Prior to incarceration, discrimination against Japanese Americans was already well underway. The FBI and other government agencies had been conducting surveillance on Japanese American communities for over a decade. When Japan attacked US military bases in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the FBI arrested Issei and ransacked their homes, tearing them from their families. The arrested Issei were “businessmen, Buddhist priests, Japanese language teachers, and other community leaders,” and most were imprisoned as “potential threats” with no evidence and without due process. These arbitrary arrests continue today, when even in this current moment we have seen cities establishing curfews (thereby manufacturing criminality where there is none) and then using said curfews to enact violence or arrest protesters who defy them. In Chicago and other cities, many of the protesters arrested during the curfews were Black. Police and FBI also surveil social media to track down and arrest protesters, indicting people “on charges of incitement to riot solely on the basis of social media posts.”

Another example of the danger of policing culture and the failure of the law were the Lordsburg Killings. Lordsburg imprisoned the U.S. Army’s largest number of Issei, with the population peaking at 1,500. On July 27, 1942, a Lordsburg guard shot and killed two physically disabled Issei who the guard said were “trying to escape.” Other internees testified that they were physically disabled and therefore could not escape, but the guard was still found not guilty. The Lordsburg Killings were not an isolated incident, and there were other cases where camp inmates were murdered by guards who were also never convicted. Today, we see many calls for murderous police officers to be convicted in court. Most of them walk free, and are re-hired in other jurisdictions even if they are fired by one.

Working towards a safer and more just future for everybody

Abolitionists understand how the rotten patterns of the prison industrial complex are the very core of the system. As Japanese Americans, our families were demonized due to racism and xenophobia, yes, but we must realize that racism and policing go hand-in-hand. The police originated as slave patrols, and we see Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities policed and sent to prison at staggeringly disproportionate rates compared to white people.

ICE “detention centers,” where immigrants are imprisoned under horrific conditions that many have also classified as concentration camps, are another example of this. The government continues to criminalize and incarcerate people that they don’t like, people that they view as a threat, people that they want to keep down. We therefore will not eliminate racism without eliminating these sites of racism, and without eliminating the mentality of policing from our own minds.

We need to get to a place as a society where we do not draw lines between “good” vs “bad” people, along racial lines or anything else. And we need to dispel the myth that incarceration is the solution, even for rapists and murderers (including killer cops). Incarceration does not stop these acts from happening. Any attempts to incarcerate people only gives the PIC more legitimacy, and the police and prisons are actually institutions that themselves perpetuate rape and murder by police officers and prison guards. So to quote Angela Davis again: “We have to talk about liberating minds as well as liberating society.”

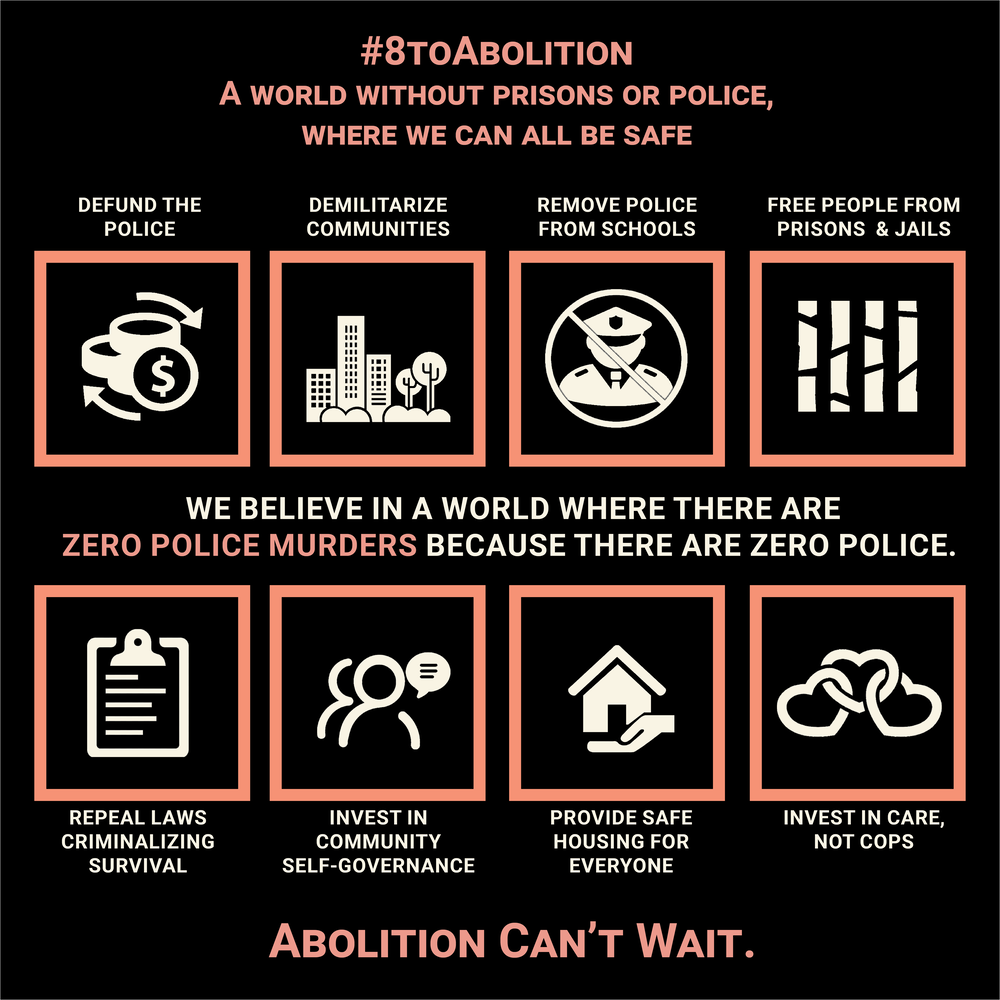

Abolitionists dream of a safer and more just future for everybody. In this future without prisons and police, resources would be invested into housing, food, healthcare, education; all sectors that build a healthy society where everyone’s needs are met. In this future, marginalized communities would not be forced into poverty, and poverty would not be criminalized. As Dean Spade says, “Being in prison has less correlation to dangerousness and more to race, poverty, and disability.” The fact is that we have an abundance of resources already. We have more than enough, but it is not being invested in communities. Abolitionists believe that by abolishing the PIC and meeting people’s needs, this world would be a much safer place.

When violence does occur in this policing-free world, justice would not mean punishment by incarceration, but accountability and healing. Abolitionists are already taking steps to make this world a reality. They are building alternatives to calling the police, creating processes for community accountability and healing outside of the state such as transformative justice, mapping support networks, running community-based murder investigations, and much more. As Ruth Wilson Gilmore and James Kilgore remind us: “Abolition is thriving.”

I do not think that we should center ourselves in this struggle, but I want Japanese Americans to recognize that we have a stake in this fight. It is also true that our community has internalized policing in many ways, by working with the police and perpetuating anti-Blackness. The harm that our community has done and our complicity in policing culture could likely be an article of its own, so I will say this—it is of the utmost importance to gain historical consciousness around the ways that we have been harmed by policing, to avoid advocating for or participating in this violence against others.

So when we talk about anti-Blackness in the Japanese American community, in addition to calling out anti-Blackness when it occurs and calling in our families, we must also think about how we can leverage our position in society and be in solidarity with Black folks. This includes acknowledging the presence of our ancestors and the intergenerational trauma that still aches in our hearts today. This includes educating ourselves in radical politics like ancestor Yuri Kochiyama and allowing ourselves to imagine and dream beyond what we have been told is possible.

“The prison system attempts to re-define who can be human. We know that we are human, and abolition requires me to ask, ‘how can the human in me see and honor the human in you?’”

—K. Agbebiyi, from the webinar “Unlock Us: Abolition in Our Lifetime” hosted by Dream Defenders

Though progress is being made, those in power are still largely only making concessions that will keep the status quo intact. Even after the protests are over, the work will continue. Although we call ourselves ‘abolitionists’, it is more accurate to call ourselves students of abolition, because we are building this new world together and there is always more to learn. Let us join the fight and organize as abolitionists, never ceasing until we obtain the future our families deserved.

—

Sara Onitsuka (any pronouns//mix it up//they/them) is a genderqueer Yonsei from Portland, OR, moving to Milwaukee, WI in the fall for a Masters in Sustainable Peacebuilding. With a background in neuroscience, they are passionate about restructuring science away from western and institutional domination and towards an accessible, anti-colonial, anti-imperialist, and anti-capitalist framework. They love to write, read, sing, and imagine and re-imagine, and are trying to understand how these pieces interact within themselves and the world. They currently organize with Asians for Black Lives Portland. Follow them on Instagram @sara_iume.

[Header photo: A photo of the author standing outside of the Tule Lake jail, holding an Abolish ICE sign made by Kelly Akemi Groth. This was during the 2018 Tule Lake Pilgrimage, where the 400+ Pilgrimage goers held a #NeverAgainIsNow rally.]