June 2, 2025

Densho Education and Public Programs Manager Courtney Wai examines why teaching the history of Japanese American wartime incarceration is especially urgent, particularly as civil liberties are threatened and immigration policies echo past injustice. At the same time, this history offers students the chance to learn about traditions of resistance and this history’s connection to inclusive education.

As educators, we have a moral responsibility to teach the full and honest history of our country — especially the stories that disrupt dominant narratives of freedom, justice, and democracy. At the same time, I know how hard this work is becoming. We’re living in a moment where the current administration is working to dismantle the Department of Education, where the right wing calls to censor uncomfortable truths, and where a vocal minority of parents are banning books — especially those centering LGBTQ+ stories and communities of color. The field of education is under attack, and the histories we’re being told not to teach are often the very ones our students need most.

It is a scary time to be an educator. But it is precisely because of this fear — because of the erasure, the censorship, the rewriting of history — that we must commit even more deeply to teaching all our histories. That includes the history of Japanese American incarceration during World War II.

More than 125,000 Japanese Americans — two-thirds of them U.S. citizens — were forcibly removed from their homes and incarcerated by their own government. This wasn’t a tragedy caused by war; it was the result of racism, wartime hysteria, and political failure, all upheld by the Supreme Court. And it’s not just a story in the past — it’s a lens for understanding our present.

The incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II shows how quickly civil liberties can be taken away — especially for communities of color.

Japanese Americans were targeted not for what they had done, but for who they were. Their incarceration was justified through rhetoric about “national security” — language that continues to be weaponized today.

I used to live and teach in Mission, Texas, along the U.S.-Mexico border, a hyper-militarized area where constitutional protections are often suspended. Within 100 miles of the border, basic rights like protection from arbitrary search under the Fourth Amendment are limited. My school was less than a mile from the border, and every day I drove past an overwhelming number of Border Patrol and law enforcement vehicles. This militarization wasn’t about safety — it was about fear, about control, and about who gets to belong.

“National security” is still used today to justify deportations without due process, to authorize raids that intimidate immigrant students, and to strip away protections that once designated schools as sensitive locations. Plyler v. Doe may guarantee that all students, regardless of immigration status, have a right to education — but what good is a right if fear keeps students from ever stepping into the classroom? And when we invoke “national security,” we must ask: whose safety and security are we actually protecting — and at whose expense? As Gordon Hirabayashi, who challenged Japanese American incarceration at the Supreme Court, reminds us, the Constitution “is nothing but a scrap of paper if citizens are not willing to defend it.”

Japanese American wartime incarceration connects directly to recent policies — especially recent policies targeting immigrants.

When we teach this history, we help students recognize these patterns of injustice, racism, and xenophobia. The current administration, along with other political leaders, has normalized many of the same, harmful tactics used during WWII. The Muslim Ban mirrors the suspicion once cast on Japanese Americans. Family separation and the detention of migrant children recall the trauma of wartime incarceration. There is even a piece of the original Crystal City Internment Camp fence now repurposed as part of the U.S.-Mexico border wall — a haunting yet literal connection between past and present.

We’re also seeing renewed attention to the Alien Enemies Act, a law used to justify the imprisonment of Japanese immigrants during WWII, and now discussed as a potential tool for further criminalizing entire communities. Even the language is familiar; the rhetoric of “enemy alien” and “invasion” has always been used to dehumanize and justify racial violence — whether it’s used against Japanese Americans in the 1940s or against immigrants, Muslims, and other marginalized communities today.

The Japanese American community offers powerful examples of resistance and resilience, equipping students with various ways to act against injustice.

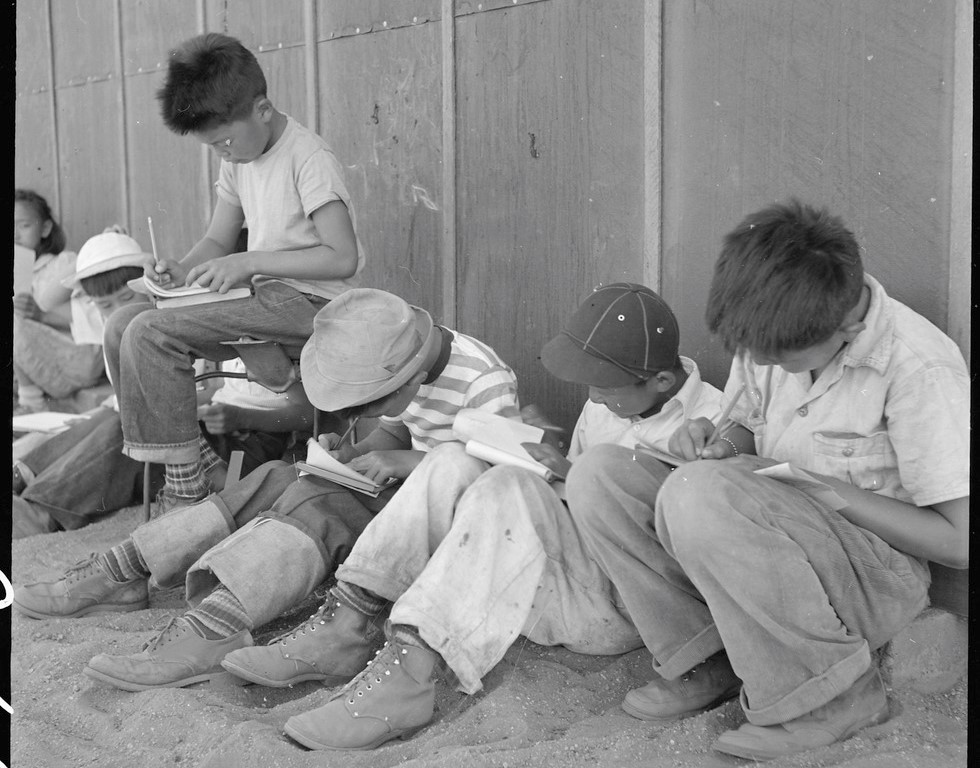

Japanese Americans resisted their incarceration in countless ways. Although most people are familiar with court challenges like Korematsu v. United States, Japanese Americans challenged their exclusion in big and small ways. They used work stoppages, hunger strikes, and protests. Some refused to serve in the military, citing their opposition to fighting for a country that was unjustly imprisoning their community. Even students criticized the hypocrisy of learning “democracy” while imprisoned behind barbed wire.

Resistance wasn’t always loud — it looked like organizing schools in the camps, planting gardens, creating art, and holding on to culture and community in a place designed to destroy both. When students learn these stories — the full range of resistance, not just the iconic ones — they learn that resistance can take many forms. They learn that ordinary people can take extraordinary stands for justice in the ways that feel right for them.

Teaching this history supports inclusive, culturally responsive education.

Teaching the history of Japanese American incarceration ensures students learn a history often erased from textbooks. It also affirms that Asian American histories are American histories — vital, complex, and necessary.

When we teach the legacy of incarceration, not just the facts, students see that this history isn’t over. Japanese American survivors — some who were incarcerated as children — are still saying “Never Again” today. They protest the detention of migrant youth at places like Fort Sill. They stand against Muslim bans and the Alien Enemies Act because they remember what it means to be targeted and surveilled based on identity. They advocate for Black reparations, standing in solidarity because they remember their own community’s fight for redress.

As educators, we must help students see how our histories are intertwined — and how our collective liberation depends on teaching the very stories that are being banned. Let’s ensure our students know how to recognize the rhythm of injustice and how to break it. Join us in teaching the full story of Japanese American incarceration. Not just for the sake of history, but for the sake of our future.

—

By Densho Education and Public Programs Manager Courtney Wai