February 4, 2025

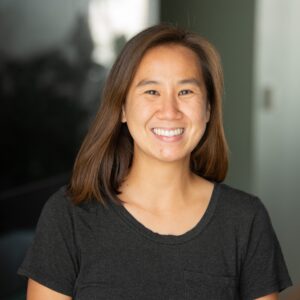

Courtney Wai began her career as a middle school English Language Arts teacher in the Rio Grande Valley and later taught English as a Second Language in San Antonio ISD. Her dedication to social justice education has driven her previous work with Teach For America, Learning for Justice (a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center), and The Asian American Education Project — and we are thrilled to welcome Courtney as Densho’s new Education and Public Programs Manager.

In a conversation with Densho Media and Outreach Manager Nina Wallace, Courtney reflects on the power of education to equip students with the knowledge they need to navigate the challenges of our present and build a more just, inclusive future.

Nina Wallace: So Courtney, can you tell me a little about your background and what made you want to be an educator?

Courtney Wai: I feel very fortunate because I grew up in Hawai`i and I had an educational experience that, at the time, I kind of took for granted, but now I realize is just very rare for most children of color in this country. I got to really see myself reflected throughout school in a lot of different ways. I got to take classes like Hawaiian history and Asian Studies. I remember in fourth grade we had this history of Hawai`i class, and we’re reading the textbook and I remember my teacher saying right away, “Captain Cook didn’t discover Hawai`i. I know that’s what it says in the book, but that’s not what happened.” I also just had a lot of teachers who looked like me growing up and shared my cultural background and lived in my neighborhood, and I didn’t realize how empowering that was until I became an adult and went to predominantly white institutions and met other peers of color who had just completely different experiences.

So even growing up, because I loved school so much and I was feeling so affirmed, I was feeling so welcome, I always knew I wanted to be a teacher. And then fast forward to college, I got a chance to take ethnic studies, including Asian American Studies, and I think all of those experiences and all of that content helped me really imagine what’s possible in K-12 education, especially when you have spaces that are welcoming, affirming, inclusive, and liberatory. I don’t think I would be so excited about doing social justice work in my everyday life, and so passionate about it if I hadn’t had those formative experiences, not just in college, but as early as elementary school.

NW: So how have you used Densho resources in your education work? Are there resources that you’ve found yourself returning to?

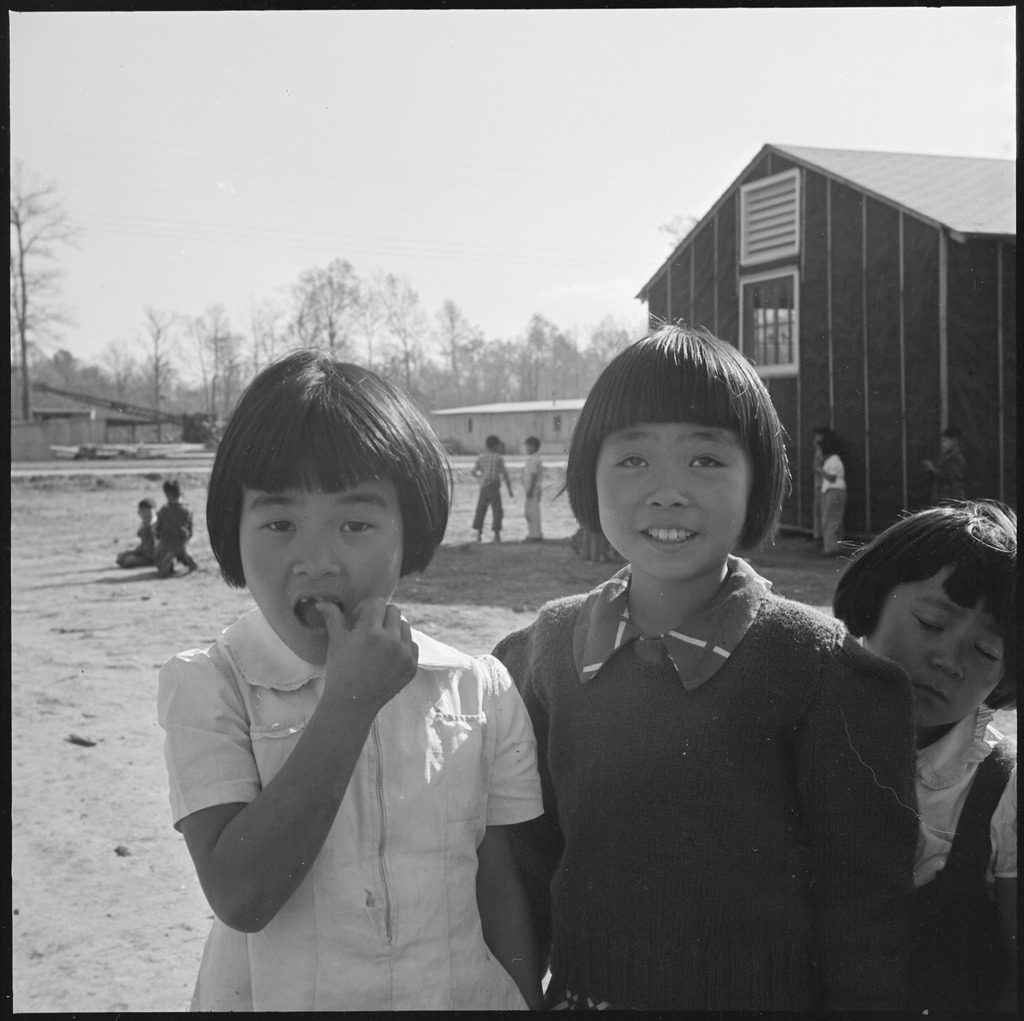

CW: I taught English as a Second Language in middle school most recently, during the 2020-2021 school year, and we had a unit focused on memoirs. I was looking for a graphic novel because one of my students said that their goal was to read a full book in English — and it is hard, right? If it’s your first year in the country and you’re just learning to speak English, it can be really hard to finish a full book. And so I thought a graphic novel would not just be fun, but also accessible and help that student reach their goals. I found George Takei’s memoir, They Called Us Enemy, and I myself needed more background because, just like most teachers and most people in this country, we’re not very well educated on Japanese American incarceration unless we ourselves have done that work. I wanted to be very specific and actually look at Rohwer, which is where Takei and his family were, and so I just used Google and the Densho Encyclopedia article on Rohwer was the first thing that popped up.

For me, it’s really important to not just teach this episode of history in a vacuum, like, “Oh, it just happened, and then we moved on.” It’s really important for students to understand how it fits into those larger contexts of racism and xenophobia and anti-Asian sentiment. So Densho was just so key in helping me develop these resources in order for my students to have that important historical and even that physical context of just, it’s so isolated in that area of Arkansas.

From that encyclopedia page, I was also able to grab photos and videos and just really great multimedia resources to help students understand what life in Rohwer might have been like, especially for young people. My students loved this one particular clip from Frank Kawana where he was talking about getting into trouble and being mischievous. I think stories like this remind everyone of our shared humanity: getting into a little bit of trouble as a kid is a universal experience and it’s just a normal part of growing up. And whether it’s a mundane story about everyday life in camp and getting into trouble with your friends, or talking about how hard life was, these are the important counter narratives that matter when you’re learning about this history.

NW: That’s so true. When I first started at Densho, I was an intern and my job was transcribing those oral histories, so that was my introduction to Densho, just spending a lot of time with the narrators and hearing their stories. And I totally agree that the human element is really what draws you in, so I’m happy to hear that’s been true for your students, too.

You touched on this earlier, how we often learn about this history in a vacuum, so I’m curious — because so much of your previous work has been around broader Asian American history as well as Indigenous history and the history of slavery in this country — coming to Densho, how do you see Japanese American incarceration as situated within that larger historical arc?

CW: That’s something that I didn’t always know as a kid — and now I know as an educator and someone who is really interested in history and how it connects to today — is that history is deeply intertwined. And it’s not often taught that way, right? I don’t blame teachers because teachers aren’t always supported in how to teach that way, but the problem with that is when we teach history as separate, distinct periods, then there’s no relation. There are these misunderstandings that proliferate til today — this idea that the past has no bearing on the present, therefore why do we need equity?

That is how I see Densho. Sharing these stories and making sure that these perspectives aren’t forgotten, that is part of a larger project around democracy in our country, in all of the good ways and all the bad ways. In the Campu podcast’s “Fences” episode, the hosts talked about how children are still being separated from undocumented parents every day in this country, and sometimes on the same sites where Japanese Americans were incarcerated. Like, there’s a piece of Crystal City that was closed down after World War II, and they dug up that fence and took it to be part of the U.S.-Mexico border in California. It’s so important for students to see the intertwined histories — not just the oppression, but also the resistance and the solidarity and the coalition building, because those models are also an essential part of this ongoing story.

NW: As I’m listening to you talk about bringing all this into classrooms — you’re based in Texas, where teaching Asian American history, Indigenous history, Black history is often restricted and even censored. So what have you learned about practicing social justice education in a place that can be very hostile to that kind of education? Are there any resources or lessons that you’d want to share with other educators who are working in similar environments?

CW: When I was last in the classroom, I always ended the year with a Student Action Project, and my ESL students decided to create a PSA about access to healthcare for undocumented immigrants. This was a very timely issue to them. One of my students had been in a detention center, and all of my students, at some point, had been separated from their families, and it hugely impacted their lives. But then later on, their videos were actually taken down. Our district cited this policy of, like, “We don’t want to teach controversial topics, and when we do, we have to have both sides.” But it’s very dehumanizing — for my students who were experiencing lack of access to health care, they already know the other side. For my student who was in a detention center, I don’t need to expose her or the rest of my students to that kind of rhetoric as to why detention centers and family separation exists. That’s not the space I want to create for my classroom. So I just want to share that as context for people to know that, when I say I understand what teachers are up against, I truly do understand.

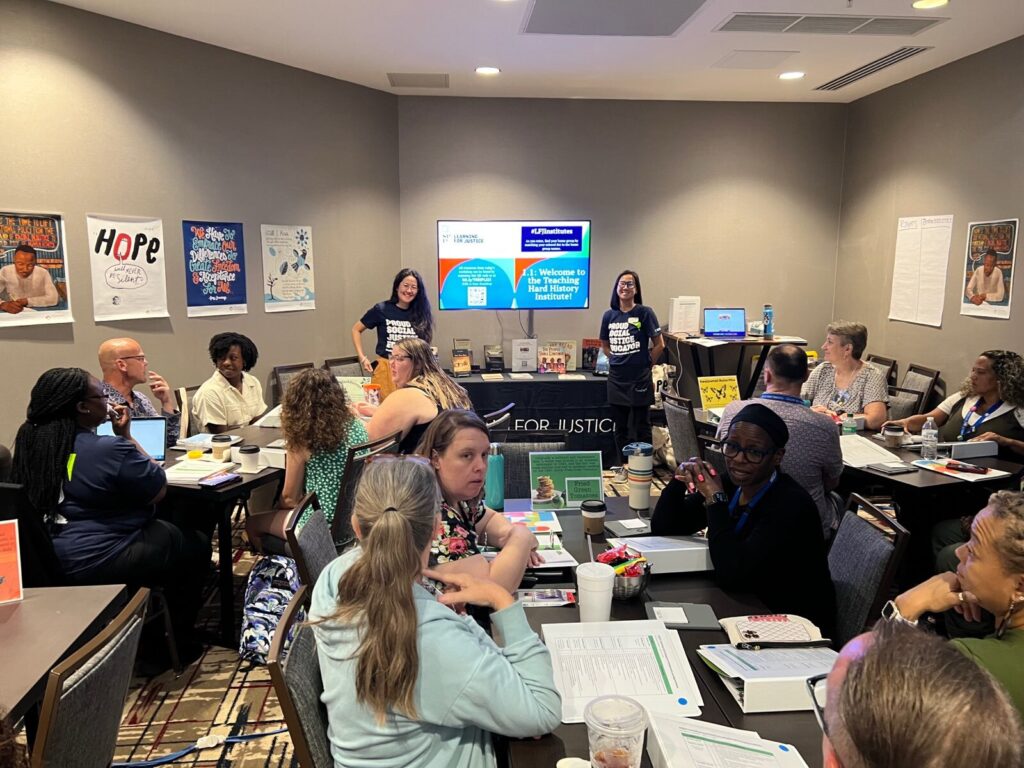

But I think there are some tools that educators can use to protect themselves, as well as their students’ perspectives. One is using primary sources. Densho is a great example — we have tons of primary sources, and these are people’s own stories. I think inquiry-based teaching is also really important. If you take the stance of asking questions, then you know you’re not indoctrinating students, as some of the arguments go. It teaches critical thinking and allows students to really wrestle with difficult issues themselves, which is also more rigorous.

Educators can also protect yourselves and protect your students by building coalitions. If you can, work with families and caregivers at your school. There are a lot of polls that show that most people support teaching honest and accurate history, and so how do we activate them? How do you mobilize them? And then, of course, just knowing your rights and your students’ rights. Undocumented students have a right to education in this country, and our LGBTQ+ students have a right to be educated in a safe and welcoming place. I encourage you to continue to build inclusive spaces for students and to give them time to process what’s happening, to talk about their fears and to build relationships with other students so that they know they’re not alone in how they’re feeling.

NW: Your experience with censorship in the classroom really illuminates the challenges that educators are facing, not just in teaching history, but also protecting and supporting their students in navigating this present moment. Given our current landscape, why do you think education work, both at Densho and more broadly, is so urgent and important right now?

CW: We are living in this moment of heightened fear and exclusion, and I think we’re all wondering, what more can I do to support students? Unfortunately, Densho is no stranger to these historical patterns of injustice and exclusion. Densho exists because Japanese Americans were incarcerated and separated from their families and their communities during a past period of wartime hysteria. So our resources can help students connect the past with the present. If students are asking, why is this happening, situating this in a larger context of history is really important. Densho’s short film Other: A Brief History of American Xenophobia is a great example of a tool educators can use to help people understand how fear and prejudice can erode civil liberties. You can only resist injustice when you recognize it, and I think that’s where Densho can be a helpful partner in the fight for social justice, including in education. We have to teach the true history of this country, and Densho is committed to supporting educators in this work, so that every single student is equipped and inspired to shape a more just and equitable future.

NW: Thank you, Courtney, I learned so much in this conversation! I really appreciate how much care and passion and commitment you bring to your education work, so I’m just so excited that you’re bringing all this expertise to Densho.

Make a gift to Densho to support the Catalyst!

[Header: Ninth graders and their teacher in a classroom at Rohwer concentration camp, November 1942. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]