August 16, 2016

Frank often had funny stories to tell his students. On the screen it looked like Frank was going to tell another one of his light-hearted anecdotes. He was smiling and excited to tell about the day his father, who had been picked up earlier by the FBI shortly after December 7th, was finally joining him, his mother, and other siblings at the Tule Lake concentration camp. Frank shared how family and friends gathered around his father in their makeshift barrack living space to welcome him. He explained how his father greeted each person with a smile and hello until he got to Frank. At this moment I was expecting a funny punch line and I was ready to laugh. Instead, Frank described how his father looked at him and said, “Who is this boy?” When Frank said these words, his voice cracked and he held back tears. Then his face softened with sadness at the memory of his father not recognizing him.

In the three years Frank’s family was separated – his father in a Department of Justice internment camp and the rest of the family in a concentration camp — Frank had grown into a young man unrecognizable by his own father. I cried as I watched this story. I cried for Frank’s sadness. But I also cried for the Japanese American community’s sadness that was hidden behind a facade of hard-working, happy faces.

Frank’s story opened my eyes to a community’s trauma hidden from view. Many Japanese Americans told me the camps weren’t that bad or that it would be better to just try to forget what happened. What I could now see was that these hidden stories of being rejected by their frightened country were a source of deep pain and suffering. These stories needed to be shared not just to document a historical event, but more importantly to ease the feelings of rejection, unwarranted shame, and sadness. And so what started out as a digital history project suddenly became much more personal and meaningful. We tapped into the emotional heart of this history, recording the feelings and unfulfilled dreams that people carried with them into the camps and to the communities they scattered to afterwards. Densho became a space for the Nisei to share deeply about what they were told to forget, and to be reminded that their stories mattered.

Similar feelings of rejection and pain are affecting other minority groups today. Many people believe our country will be safer if we banned Muslims from coming to America, that the detention of immigrant families is justified, and that the “Black Lives Matter” movement has nothing to do with them. We have neighbors who feel pain, sadness, and anger because they are depicted as dangerous and face violence and discrimination because of how they look. No matter what they do or who they are, they are too often misunderstood and feared. These are the individuals whom I call brothers and sisters, and I stand proudly with them because that solidarity is what will help make us a “more perfect union.”

The stories Densho has collected for the past twenty years put faces, names, and emotional responses to a part of our history that many Americans would just as soon forget. Densho’s mission is to share these stories so we remember the mistakes of the past, and promote equity and justice over racism and bigotry today and in the future.

On September 24, Densho will host a gala to commemorate our first twenty years, but also to initiate a community dialogue about how the legacy of WWII incarceration can be used for social justice today. Please consider participating in and supporting this work by joining us at the gala. Information and tickets can be found at www.densho.org/20thanniversarygala.

—

By Tom Ikeda, Executive Director of Densho

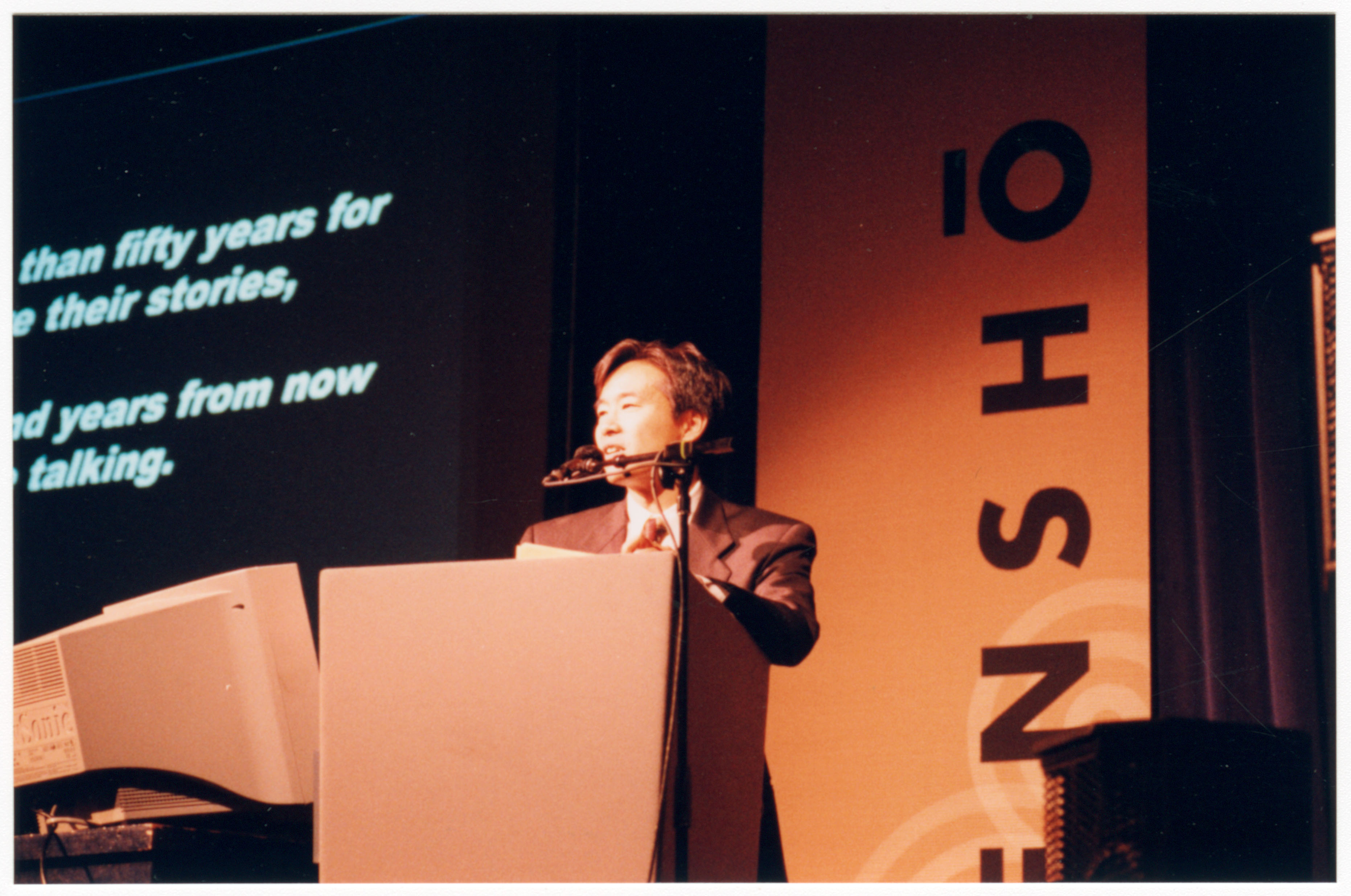

[Blog header: And the Tom speaking one was at an event on November 22, 1998 at the Nippon Kan Theater in Seattle. The event was to celebrate the installation of Densho workstations (the first, non-web version of our archive with 100 interviews and 1000 photos) at the Wing Luke Museum. 700 people attended.]