July 10, 2018

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the signing of the Civil Liberties Act, with which the United States closed the book on Japanese American incarceration. Closed the book, with the overbearing hand of both the proud, proprietary storyteller and the person who is tired of, though more accurately haunted by, the story. The question now, 30 years later, is whether or not the book is in fact over. I risk preempting the question by saying that any history that still possesses the power to generate silence and denial, violence and shame, and seemingly boundless and unbroken reincarnations of injustice, is a history that has not ended.

The stated purposes of the Civil Liberties Act were to: (1) acknowledge the fundamental injustice of incarceration, (2) apologize on behalf of the people of the United States for the incarceration, (3) provide for an education fund to inform the public about incarceration, (4) pay reparations to those who were incarcerated, including (5) the Aleut people of Alaska, (6) discourage the occurrence of similar injustices and violations of civil liberties in the future, and (7) make more credible and sincere any declaration of concern by the United States over violations of human rights committed by other nations.

This last one seems erroneous, at first, then revealing. Erroneous because the United States is pledging an effort at credibility and sincerity in its concerns over human rights violations, not an effort at eradicating them. Revealing because its concerns are over, more specifically, human rights violations committed by other nations.

In other words, the Civil Liberties Act concludes by deflecting the burden off the United States and onto the rest of the world, while further entrenching the United States as the world’s self-appointed law enforcement. There is no error in American acts, only the amnesiac expectation of the people on which they are imposed. As Frederick Douglass said, in a speech delivered on August 3, 1857: Power concedes nothing without a demand. [1]

***

82,219 Japanese American citizens and legal residents received reparations in the form of $20,000, to account, as a formality, for what they had lost. Or, because loss is a euphemism for theft, what had been stolen. The Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) requested from Congress that each prisoner receive $25,000, a figure revealed to have been underestimated and arbitrary. The Office of Redress Administration, created by the Civil Liberties Act, paid out a total of 1.6 billion dollars. The first nine checks were presented to nine of the oldest prisoners in a ceremony in Washington D.C., October 9, 1990.

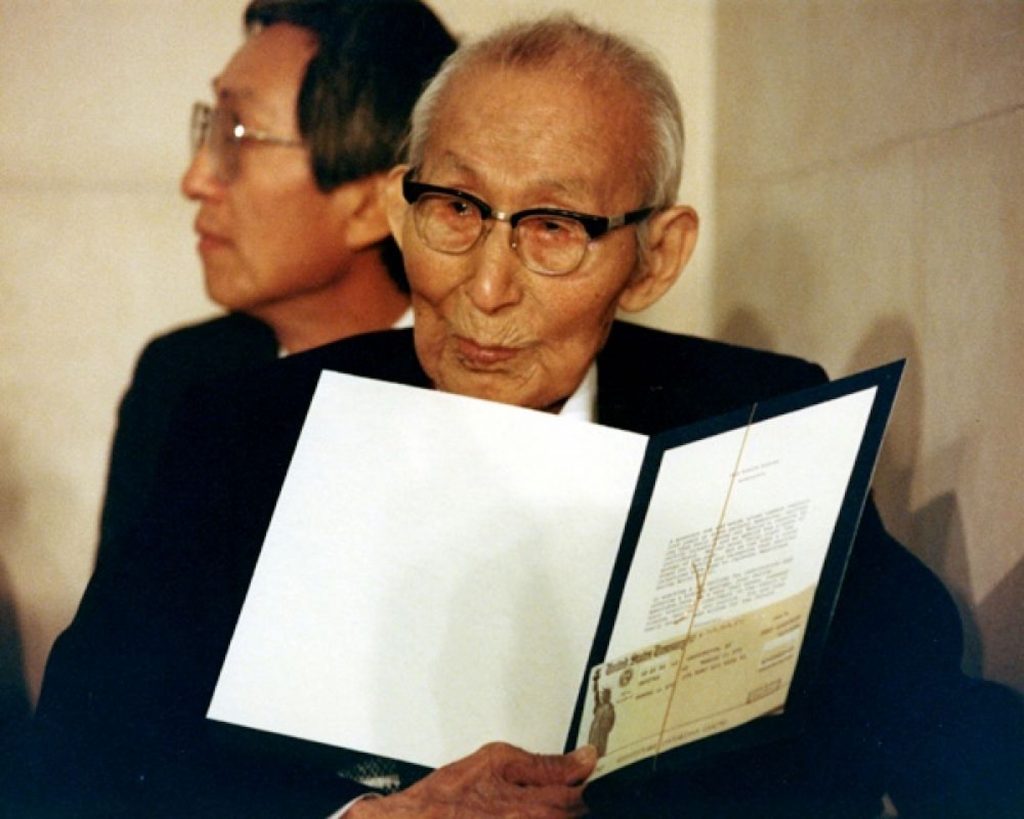

Mamoru Eto, a 107-year-old preacher living in the Keiro Nursing Home in Los Angeles (where my great-grandmother, Asano Yamashita, also lived, and died), was the first to receive a check. Keiro means: respect the elders.

Eto fought in the Russo-Japanese War, the first war in which the enemy was illuminated, by searchlight, the moment they were being killed. Eto immigrated from Taketa, in Oita Prefecture, to the United States, in 1919. He and his wife Kura, also from Japan, settled in Pasadena, where they had ten children. Eto was a gardener during the week, a preacher on weekends. Kura eventually returned to Japan, alone. Mamoru and seven of their children—three had already left California—were incarcerated, first in the Tulare detention center, then in Gila River, Arizona. Even though he was not, at the time, eligible for US citizenship, Eto forswore his allegiance to Japan. We’re not Japanese anymore, he said. We’re American. Adding: There’s no other way. [2,3]

Another of the 82,219 to receive reparations was my great-uncle, Makeo, who is dead. Another was Makeo’s wife, Tsuruyo, who is also dead. Another was my cousin, Sally, who is alive, and has very little to say about it. Another was my cousin, Donna, who is also alive, and who also has very little to say about it. Another was my great-aunt, Joy, who is also alive, does have things to say about it, but only recently starting saying things about it, including to her children, who are in their forties, and did not, until recently, know very much about their mother’s 3½-year stint as an enemy of the United States.

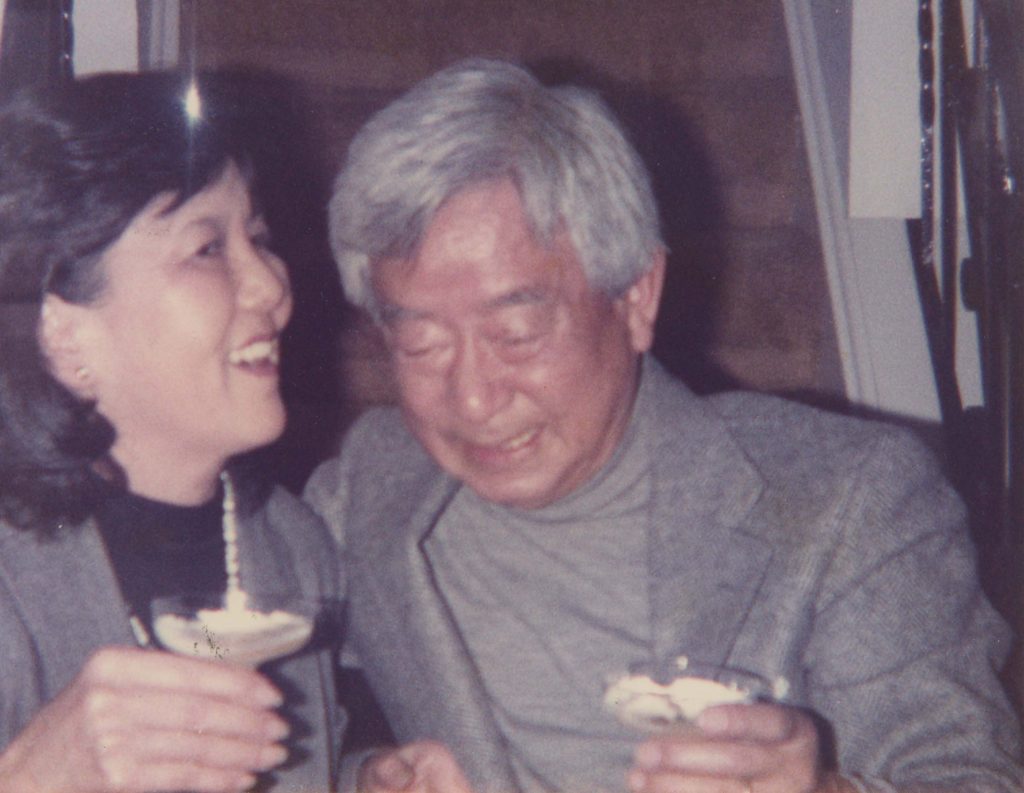

And yet another of the 82,219 to receive reparations was my grandfather, Midori Shimoda.

Born on an island off the coast of Hiroshima, he immigrated to the United States, alone, in 1919. He had been in the United States for twenty-two years by the time of Pearl Harbor, but was, with all Asian immigrants, ineligible, by law, for citizenship, so was a Japanese national, or, in the parlance of white hegemony, an alien. On December 7, 1941, he became an enemy alien.

My grandfather used the reparations to pay for his first year in the nursing home where he spent the last five years of his life.

My grandmother received a check for $20,000. She spent it immediately on my grandfather’s rent. He never saw it. He did not know anything about it. He was ten years into Alzheimer’s. He did not know he had, fifty years earlier, been incarcerated, with approximately 1,000 Issei men, in a Department of Justice prison in Missoula, Montana, under suspicion of being a spy for Japan.

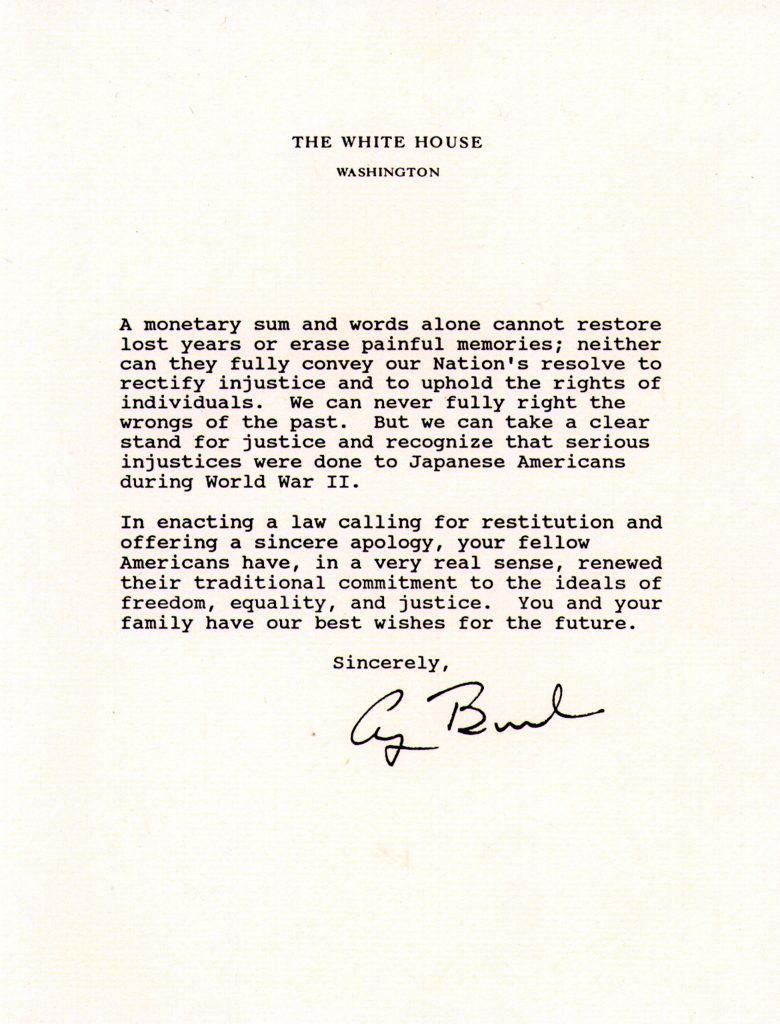

The check was a coin placed in my grandfather’s mouth. It came with a letter: a form apology from the White House.

It was not addressed to my grandfather. It was not addressed to anyone. There was no salutation. It was stamped with the signature of Bush I. The last sentence read: You and your family have our best wishes for the future. Five years later, my grandfather was dead.

His funeral was held in a nondescript church in a small town in North Carolina. It was a Sunday. The church was filled with white people my grandfather did not know. He had never been in the church. The funeral was in a side room. There were a small number of Japanese Americans, but they were outnumbered twenty-to-one by white people, most of whom paused on their way into the sanctuary, saw the photograph, surrounded by flowers, of a Japanese man, and thought, oh, that Oriental man is dead.

I use Oriental advisedly. I also use it honestly. In the small town in North Carolina—which was, in 1996 (the year my grandfather died), 96% white, 3% black, all other ethnicities, including three Japanese Americans (my grandfather, my grandmother, my aunt) making up the remainder—Oriental was more common than Asian, as if Asianness could not be perceived outside of objectification.

How much is $20,000 not? Reparations paid for one year of my grandfather’s dying. I asked my grandmother recently about the check. If she remembered receiving it. She did not. I had to remind her what it was. My grandmother, June (Chizuko Yamashita) Shimoda, is Nisei. She was born and, except for two years in Fukuoka, raised in Utah, which fell outside the exclusion zone. She and her family were, therefore, exempt from incarceration, which must have seemed both fortuitous and perplexing, given that they did not live far from Topaz, where 8,130 Japanese Americans were incarcerated. The check, my grandmother said, did not arrive automatically. Someone told her about it. She could not remember who, or what she did. Somehow the check arrived. But it did not inspire conversation. Any sense of vindication that might have been felt—in my family, at least—was personal, private, swallowed. The check was deposited. The letter disappeared just as quickly.

***

The Civil Liberties Act was signed by Reagan, August 10, 1988. In photographs, Reagan looks, sitting at a wooden desk, surrounded by men, Japanese American and white, and one Japanese American woman, like a child learning how to write his name. The men and women are smiling, practically leering. In one photograph, Reagan looks like he is painting a watercolor. In another, he is holding the pen triumphantly in the air, while everyone hovers around him, applauding. [Ed. note: See header photo.]

One month before James Baldwin died, he was asked, by the poet Quincy Troupe, what he thought Reagan represented to white America. Baldwin answered: Ronald Reagan represents the justification of their history, their sense of innocence. The justification, in short, of being white. [4]

In nearly every caption where the photographs of the signing of the Civil Liberties Act have been reproduced—including in memorials conceived by Japanese Americans—only Reagan is named. [5] The historical moment is being handed, unanimously, to him, while the people crowded around him, codependent, redacted, become ghosts.

With Reagan redacted, however, the Japanese Americans look like they are admiring, with the air of magi—angels? vultures?—a corpse spread out upon a bier. Left to right: Masayuki Spark Matsunaga, Nisei from Hawaii, served in the Hawaii Territorial Legislature, then in Congress, for four decades, and was the main Senate sponsor of the Civil Liberties Act. He served with the primarily Japanese American 100th Infantry Battalion in WWII. Norman Yoshio Mineta, Nisei from California, was incarcerated in Santa Anita then Heart Mountain. He was the first Japanese American outside of Hawai’i to be elected to Congress and the first Asian American to serve in a presidential cabinet. He was the Secretary of Commerce in the Clinton Administration. He was the Secretary of Transportation on 9/11. He issued the nation’s first order to ground all civilian air traffic. He also explicitly ordered airlines to refrain from the racial profiling of passengers, Middle Eastern in particular. Patricia Saiki, Nisei from Hawai’i, was the first Republican Congressperson to represent Hawai’i after statehood, and was instrumental in garnering (the ultimately scant) Republican support for the Civil Liberties Act. Robert Takeo Matsui, sansei from California, was six months old when he was incarcerated in Pinedale then Tule Lake. He was the second Japanese American, and the first Sansei, elected to Congress. Hitoshi Harry Kajihara, Nisei from Oyster Bay, Washington, was incarcerated in Tule Lake. He helped to raise over half-a-million dollars for redress, and later became the national president of the JACL.

With Reagan redacted, however, the Japanese Americans look like they are admiring, with the air of magi—angels? vultures?—a corpse spread out upon a bier. Left to right: Masayuki Spark Matsunaga, Nisei from Hawaii, served in the Hawaii Territorial Legislature, then in Congress, for four decades, and was the main Senate sponsor of the Civil Liberties Act. He served with the primarily Japanese American 100th Infantry Battalion in WWII. Norman Yoshio Mineta, Nisei from California, was incarcerated in Santa Anita then Heart Mountain. He was the first Japanese American outside of Hawai’i to be elected to Congress and the first Asian American to serve in a presidential cabinet. He was the Secretary of Commerce in the Clinton Administration. He was the Secretary of Transportation on 9/11. He issued the nation’s first order to ground all civilian air traffic. He also explicitly ordered airlines to refrain from the racial profiling of passengers, Middle Eastern in particular. Patricia Saiki, Nisei from Hawai’i, was the first Republican Congressperson to represent Hawai’i after statehood, and was instrumental in garnering (the ultimately scant) Republican support for the Civil Liberties Act. Robert Takeo Matsui, sansei from California, was six months old when he was incarcerated in Pinedale then Tule Lake. He was the second Japanese American, and the first Sansei, elected to Congress. Hitoshi Harry Kajihara, Nisei from Oyster Bay, Washington, was incarcerated in Tule Lake. He helped to raise over half-a-million dollars for redress, and later became the national president of the JACL.

***

Aside from apologizing for Japanese American incarceration, the United States has officially apologized five times.

The United States apologized for protecting Klaus Barbie, a Gestapo agent responsible for the deaths of 14,000 French prisoners during WWII. The United States enlisted him, with other Nazis, for counterintelligence operations, eventually coordinating his escape to South America. The apology came in 1983.

The United States apologized for backing a coup, led by white businessmen, to overthrow Queen Lili’uokalani and the Kingdom of Hawai’i, in 1893. The apology came one hundred years later, in 1993.

The United States apologized for the Tuskegee Experiment, in which 600 black men were subjected, without knowledge or consent, to medical testing that was purportedly to study the progression of syphilis, and which was supposed to last six months. It lasted forty years, and none of the men were either treated or cured. The apology came 65 years after the tests began, in 1997.

The United States apologized for the fundamental injustice, cruelty, brutality, and inhumanity of slavery and Jim Crow. Slavery in the United States dates back to 1619, and was abolished in 1865. Jim Crow spanned a century. The apology came in 2008, with the caveat that reparations were off the table.

The United States apologized to all Native Peoples for the many instances of violence, maltreatment, and neglect inflicted on Native Peoples by citizens of the United States. The apology is buried in Section 8113 of an otherwise unrelated bill, the Department of Defense Appropriations Act of 2010.

Apologos (Greek): an account, a story. Apology consigns a transgression, a crime, to the past, while expecting, more often demanding, forgiveness, in the present, therefore the future, even (especially) if the transgression has transformed, therefore not ended. It puts the burden of responsibility of historical closure on the victims, those still suffering, to forgive, accept their fate, absorb the apology and become its missionaries, preach its word. Shut up and move on.

By focusing exclusively on removal and incarceration as singular events, bounded by Pearl Harbor and the Civil Liberties Act, the United States eliminated the greater, and congenital, context of anti-Japanese and anti-Asian and anti-immigrant anxiety and rage and their enshrinement in racist legislation.

Incarceration became, in the mind of the Civil Liberties Act, and the motivations of its Apologos, a temporal, therefore circumstantial injustice, and in the process, freed the United States from a guilt beyond its capacity to simulate, let alone genuinely feel. It also freed the United States, under the auspices of amnesia, to continue its pathological project by other means.

![]()

Here, in no particular order, are the components that made Japanese American incarceration. The question is whether we recognize these as being relics from the past, or permanent features (in 2018, always) of the insatiable state of exception: anti-immigrant propaganda; racial profiling; warrantless surveillance and the maintenance of (not-so) secret databases; warrantless raids; media complicity in fomenting anxiety and rage; the separating of families and the (subsequent) devastation of families and family structures; the severing of people from their ancestry, their origins; the criminalization of language and culture; perpetual and arbitrary tests of allegiance; forced submission to the ideologies and behaviors of national security citizenship; forms of social control derived from penitentiaries, plantations, and Native reservations; the occupation of Indigenous land; the dispossession and theft of property; exploitative labor; a Constitution so reliant upon interpretation, and so unequally applied, as to be completely subjective; mass incarceration.

If these things made Japanese American incarceration, and these things still exist, more forcefully and, until recently, with greater subtlety, than they did in 1942, then how can we say that Japanese American incarceration has ended? We can say it by stripping Japanese American from incarceration, by turning Japanese American into a modifier. With the Civil Liberties Act, the United States deconstructed the apparatus of Japanese American incarceration and resurrected it across the entire spectrum of American existence.

***

There has been, the past few years, a resurgence of stories and testimonies, memorials and exhibitions, about incarceration. The last time Japanese Americans spoke so openly, so volubly, about incarceration was in the years leading up to the Civil Liberties Act. Over 700 testimonies were delivered before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. The stories ran the gamut of emotion and experience, and were not entirely, or at all, free of the anger, indignation, resignation, self-doubt and shame, that have kept them unresolved. Some stories manifested as silence. Silence too is a story, one that requires the prodigious, sometimes eternal, patience of its listeners.

Though the testimonies were imperative and cathartic, they amounted, politically speaking, to a law that foreclosed on the agency, the viability, of future testimonies. Stories, stripped of political agency, grew inward. Feelings of discomfort and disease were internalized as personal failures. The arrested parts of survivors’ selves, and their parents’ and grandparents’ selves, manifested the unexplainable phenomenon of being haunted by that which was believed to have already been resolved.

Japanese Americans who were born in the camps are now in their seventies. Those most likely to remember, and with the greatest clarity, are in their late-seventies, eighties, and nineties. The memory of incarceration is going to pass, very soon, into the province of those who were not there, Sansei and Yonsei and Gosei children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren. That is partially wishful thinking, though; memory is submitted by power to its partisans, by whom memory is attenuated, if not perverted, and beneath whom the oppressed become an unnamed undercurrent. Both the nature and content of the transference of memory is vulnerable, risking the kind of resolution, or patina, that insists that what cannot be incorporated into memory is suspect, if not superfluous.

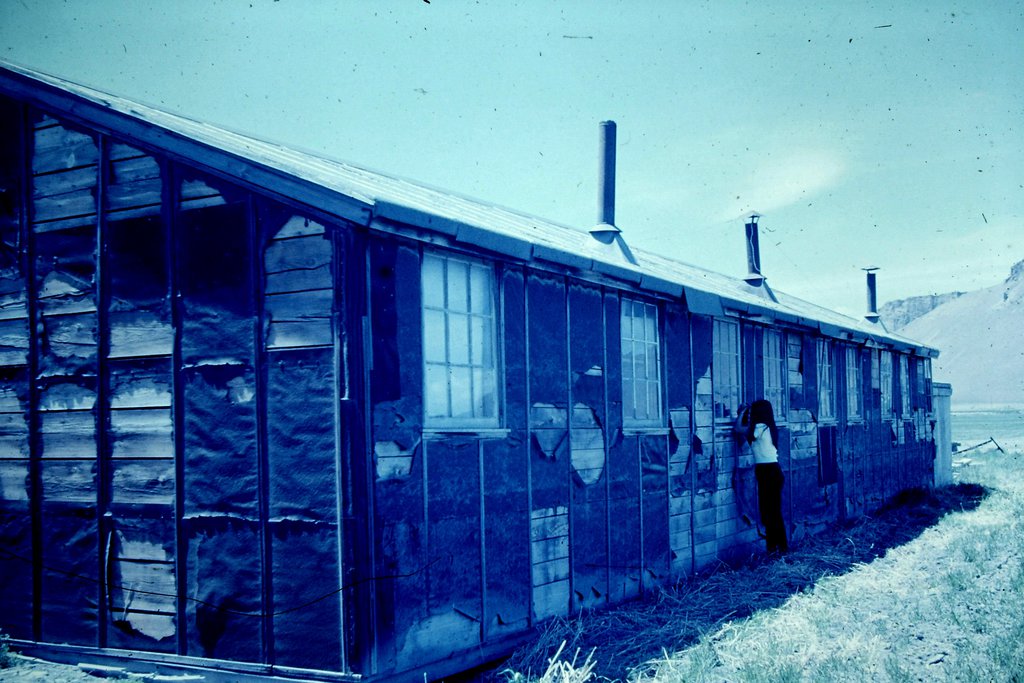

But the ruins are not an expression of the past. They are the revelation of the present. And they have been revealing themselves, ad infinitum, especially in recent years (more specifically: days), during which spectacular violations of civil rights have become distressingly un-spectacular. [6]

The ruins exist in the numerous incarceration sites, not only the ruins of the ten main concentration camps, but the dozens of detention centers and Department of Justice prisons and labor camps and isolation centers and immigration stations, most of which are rarely, if ever mentioned, all of which are accessible and simultaneously as hidden from view as they were intended to be.

And the ruins exist in the ways the experience of incarceration has been inherited, as well as in the ways that inheritance is being cared for and put to use. Stories and testimonies. Memorials and exhibitions. How reparations were spent. Dispersed, disappeared. Facial expressions. Hands. The way an heirloom is held. All of which, for reasons ranging from retribution to patriotism to indifference and dementia, have as great a capacity to enable, obscure, erase, as they do to illuminate.

In the ruins, every facet—whether apparent, oblique or mundane—becomes, like a flower growing out of a decaying foundation, charged with disclosure.

—

Brandon Shimoda is the author of several books, most recently Evening Oracle (Letter Machine Editions), which received the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America; The Desert (forthcoming this fall from The Song Cave); and his first book of nonfiction, an ancestral memoir, The Grave on the Wall (forthcoming in 2019 from City Lights). His writings on Japanese American incarceration have appeared in The Asian American Literary Review, Design Week Portland, Entropy, Hyperallergic, The Margins, and The New Inquiry. He is on Twitter @brandonshimoda.

This is an abridgment/adaptation of a talk originally delivered at Fairhaven College in Bellingham, WA, on March 7, 2018. For a more comprehensive account of the Civil Liberties Act, visit the Densho Encyclopedia.

—

Notes

1. Frederick Douglass, West India Emancipation speech, Canandaigua, New York, August 3, 1857.

2. Barbara Koh, Breaking the Long Silence: Mamoru Eto, Los Angeles Times, November 25, 1990.

3. One way of becoming American is by getting involved in organized crime. Mamoru’s son Ken was the highest-ranking Asian American in the Chicago Outfit, the mob syndicate founded by Al Capone. He learned how to gamble while incarcerated in Minidoka, and later ran a gambling racket in Chicago for over thirty years. It was broken up by the FBI. An assassination attempt, from inside the Outfit, was made on Ken’s life. He survived three shots to the back of his head. The bullets ricocheted off his skull. He agreed to become an informant for the FBI. The investigation was called Operation Sun-Up. He testified, in black hood with eyeholes, against fifteen of his Outfit associates, including policemen. They all went to prison. Eto entered the Witness Protection Program, and died, in 2004, under the pseudonym, Joe Tanaka. His aliases included: Joe Montana, Joe Eto, John Ito, Joe Nakamura, Joe Keneto, Tokyo Joe, Joe the Jap, and The Chinaman.

4. James Baldwin interviewed by Quincy Troupe, St. Paul de Vence, France, November 1987. In The Last Interview and Other Conversations.

5. See, for example, Reagan’s place in the the Japanese American Historical Plaza, in downtown Portland, Oregon, which I wrote about at The New Inquiry.

6. In State of Exception, Giorgio Agamben refers to Japanese American incarceration as a spectacular violation of civil rights, and directs us to the eighth of Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History, which states: the tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the “state of emergency” in which we live is not the exception but the rule.