August 25, 2022

The second largest of the so-called “assembly centers” with a peak population of 7,816, Tanforan was built on the site of the Tanforan Racetrack in San Bruno, California, near the present site of the San Francisco International Airport. Its inmate population arrived in late April and early May 1942, and came almost entirely from the San Francisco Bay area and was thus among the most urban of the short-term camps. Essentially the entire inmate population was transferred to the Topaz, Utah, concentration camp in September 1942.

It is now the site of a shopping center and BART station—and just a couple of blocks away from the San Bruno branch of the National Archives, where records on the “assembly centers” are held. Here are ten noteworthy aspects of the Tanforan detention site.

Horse Stall “Apartments”

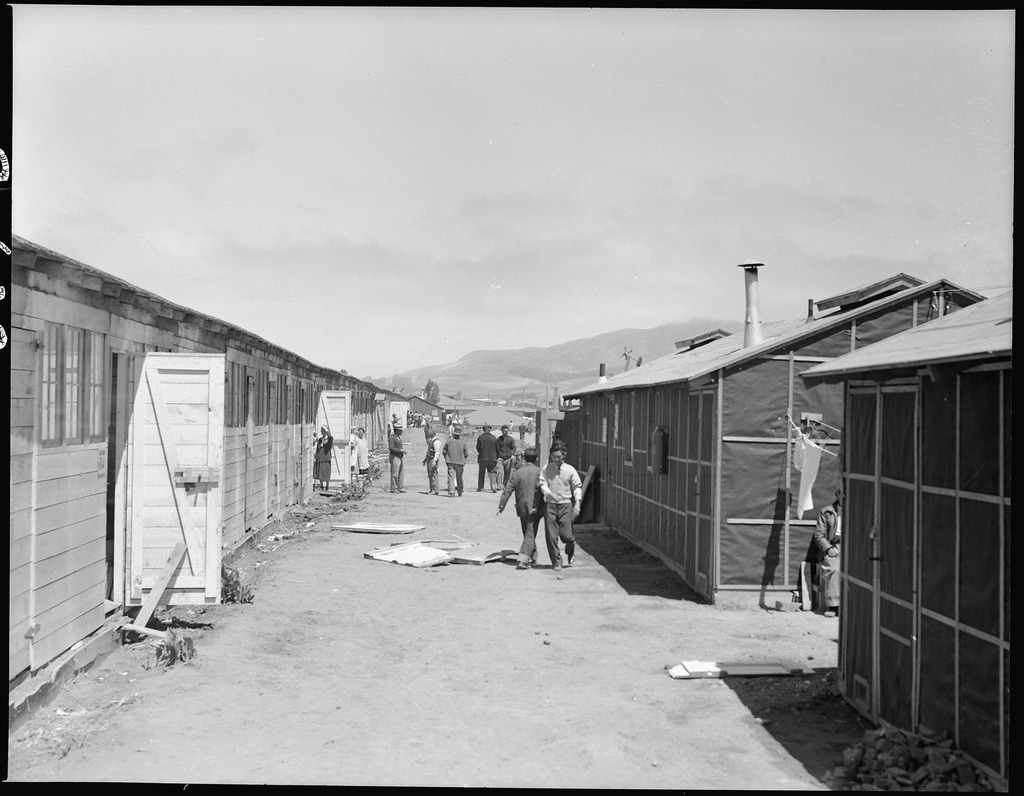

Tanforan was one of two “assembly centers” that held nearly half of its inmate population in converted horse stalls. Twenty-six horse stables—most of which consisted of fifty stalls—were converted into “apartments” that held the first groups to arrive. Three to six people typically lived in a 10 x 20 stall that had housed one horse. Each stall was divided into two sections by a swinging half-door; the front section had two small windows, the back section was windowless. In most cases, the stalls had linoleum floors that had been laid over manure stained boards, and the smell of the prior occupants remained behind. As with the newly built barracks, the stalls were initially furnished only with one army cot per person and had a single light bulb for lighting. As with the barracks, walls stopped short of the roof, allowing sound to travel throughout the stable. Just under half of Tanforan inmates were held in these converted stables, about 3,700 out of a peak population of 7,816. Later arrivals were assigned to the newly built barracks that presaged the barracks found in the War Relocation Authority (WRA) concentration camps.

Not surprisingly, most contemporaneous accounts expressed distress about being forced to live in horse stalls, citing the smell, the lack of privacy, the mud, frequent power outages, leaky roofs, and the utter indignity of the situation. “When I saw the place for the first time, I was twice as dejected and the vague spark of hope that I had kept in a secret corner of my mind died out. What else could I think as I was put into a musty stable with a fence surrounding the camp?” remembered Kiyoshi Jimmy Kimoto in a 1944 interview with Charles Kikuchi. “That the stalls should have been called ‘apartments’ was a euphemism so ludicrous it was comical,” wrote Yoshiko Uchida in her camp memoir, Desert Exile.

What is a bit surprising is that some inmates felt that there were advantages to the horse stalls relative to the newly built barracks. In a May 17, 1942 letter to a friend, Fred Hoshiyama wrote that his stable unit was “better than the new barracks cause it doesn’t get too hot on hot days and too cold on cold days. New barracks are new, but no privacy and it gets too cold or too hot.” A Tanforan Totalizer article cited one group of stables that “were built more substantially than many of the others in Tanforan.” The administration also distributed the limited number of cotton mattresses—versus tic mattresses that had to be stuffed with straw—to those in the stables. But stables or barracks, it was clear that this was concentration camp life.

“Deplorable” Bachelor Housing

For the first few weeks, a large room under the grandstand that had been the area where horse racing fans placed their bets was used as a dormitory for single men. A large room about one hundred yards long, it housed between four hundred and five hundred men in beds separated by one-and-a-half to two feet. In his diary and letters, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) fieldworker Tamotsu Shibutani called the dormitory “an appalling sight” and and “a hellhouse if I ever saw one.” “The place is filthy, stinky, foul, etc,” he wrote. “I don’t see how anyone could live in a dump like that one and stay sane.” Michio Kunitani referred to it as a “deplorable situation” that saw the men “crowded together in one huge, poorly ventilated room.” Charles Kikuchi reported upon visiting the room “the odor that greets you is terrific. What a stench! They don’t have any fresh air circulating around and the old clothes and closeness of body smells doesn’t help out any.” The various chroniclers also reported rampant gambling, domination of the space by “Japanese men cluster[ed] around the radios blowing the latest news and discussing the final Japanese victory,” and even rumors of prostitution.

After a month, the administration decided to close down the dormitory—according to Fred Hoshiyama it was at the behest of the San Mateo County Health Department—and redistribute the single men into regular barracks. This caused a small panic in those barracks, given the reputation of dormitory denizens, and inmates covered openings in and above barrack walls with cardboard and women put boards up next to latrine seats closest to the door. The space was later converted for use by the high school.

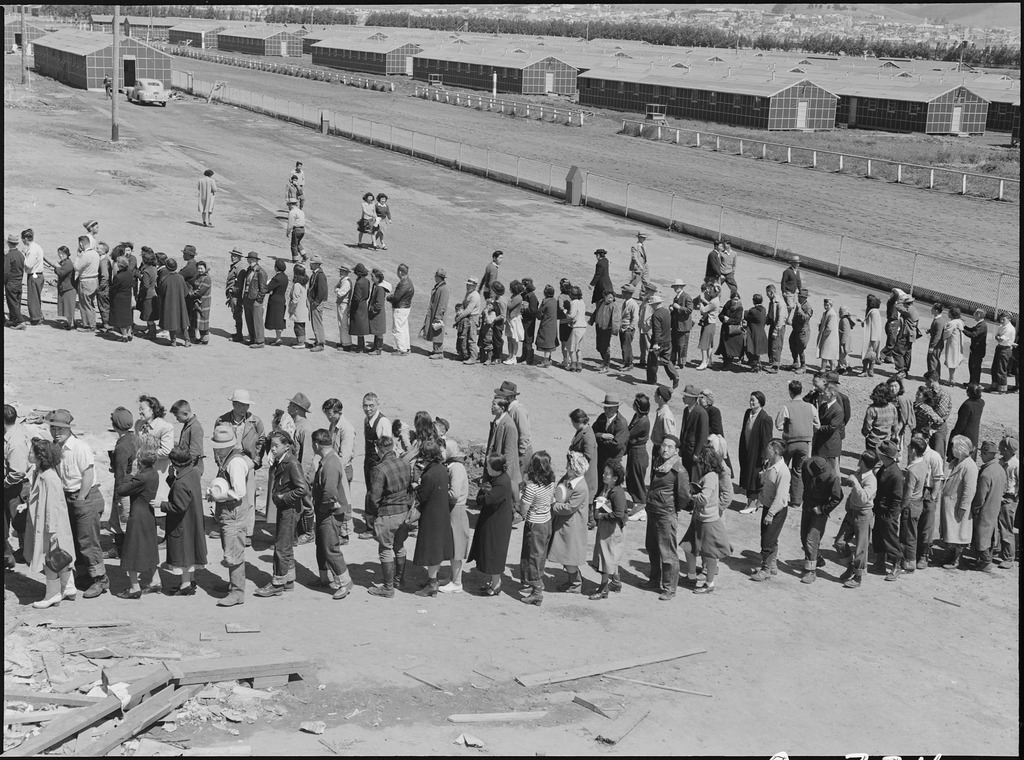

One Mess Hall for 3,000 People

As with many of the camps, there were unexpected problems in the early weeks of Tanforan. One was a shortage of kitchen equipment that delayed the opening of the mess halls so that there was only one in operation for the first couple of weeks. Located in the grandstand area just below the bachelor dormitory, the large mess hall consisted of one large room perhaps 150 yards long with rows of tables. Upon his arrival on May 1, Tamotsu Shibutani noticed a line forming forty-five minutes before mealtime and was told to get in it, since there would not be enough food for everyone. In a later co-authored report, he wrote that the “food was not fit for human consumption, and many refused to eat.”

In addition to shortages and crowding, the situation was made worse by the first mess manager who had ordered food for May and June without understanding the preferences of the inmate population and thus ordered “such items as chili con carne and sauerkraut” instead of fish or rice. While mess halls began to open in other parts of the camp by mid-May, the grandstand mess hall retained “the reputation of being the filthiest, the most unsanitary, and the least desirable eating place of all” according to Shibutani and his collaborators. In a May 18 letter, Fred Hoshiyama reported that the main mess hall still had to feed nearly 3,000 people—since inmates had continued to arrive—and that long lines persisted. A few days later, Hoshiyama wrote to Lincoln Kanai about a mass case of food poisoning when spoiled ham sickened 400 people.

Lake Tanforan

In the “assembly centers,” and later in the longer-term WRA camps, inmates found ways to beautify their surroundings by creating gardens and parks. Because inmates received little information early on as to whether they would remain at the “assembly centers” or move to larger camps, most of the camp population treated the “assembly centers” as their final destination during the war. At Tanforan, the inmates constructed a small lake at the center of the racetrack to serve as a recreation place. JERS staffer Tamotsu Shibutani described the lake in his first report on life at the Tanforan Assembly Center, noting the lake’s use as a meeting place: “On May 10, a Mothers’ Day Service was held at Lake Tanforan, a mud hole in the infield (within the tracks).” Two weeks later, on May 24th, a Flag Day ceremony was held by the lake. The ceremony included a performance by the camp’s Boy Scout Drum and Bugle Corp, and included performances of the National Anthem and a reciting of the Pledge of Allegiance. Over 6,000 people attended, including the majority of the camp population and the camp staff. Despite the lake’s small size, children built small boats to float on the lake. At one point, JERS staffer Charles Kikuchi recorded in his diary that his brother Tom built toy boats that sailed on Lake Tanforan, although most of them sank.

Inmate Yukiko Kimura described the lake as being a source of pride among the confined, with a small park built around the lake and a bridge added: “This lake was the outstanding improvement that the Japanese here have made here at Tanforan. When we first arrived the side of the lake was only an unattractive, dried-up hole in the ground. The men built up its sides, planted trees, made a picturesque arbor, and as the crowning achievement, built a marvelous bridge… out of logs in ‘neither American nor Japanese but in typical Tanforan style.’ It was then filled with water, and the end result was a transformation which seemed to be little short of a miracle.”

Nisei Collegians

Given its urban population and proximity to Bay Area colleges, it is likely that there was a higher concentration of college students at Tanforan than at most other “assembly centers.” Though most were not immediately able to continue their education, there were a few who were able to leave Tanforan to attend college—and thus avoid going to a WRA concentration camp—often with the assistance of the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, which formed at the end of May 1942.

Among them were former UC Berkeley students Masako Amemiya and Lillian Ota. Largely through her own initiative, Ota was able to secure a scholarship to Wellesley and later became something of a poster girl for the possibilities of Nisei collegians for the council and WRA. Amemiya’s journey was a bit bumpier. Also a Berkeley student when incarcerated, she gained admission to Elmhurst College in Illinois with the aid of the NJASRC. But just as she was preparing to board the train east, her trip was canceled due to adverse reaction from the local community. Fortunately, an alternative was found in fairly short order, and she ended up leaving for Cornell College in Iowa, where she reported a positive experience.

The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study

Given that the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) was based at the University of California at Berkeley, it should not be surprising that several student fieldworkers—along with some who were not students—were at Tanforan, documenting various aspects of the camp. They included Doris Hayashi, Fred Hoshiyama, Ben Iijima, Charles Kikuchi, Tamotsu Shibutani, and Earle Yusa among others. (You can learn more about each from the linked Densho Encyclopedia articles.) Though the JERS project was controversial due to the ethical dilemma of conducting research in concentration camps and lack of consent from subjects, there is no question that the various reports and diaries produced by these researchers have contributed to Tanforan being perhaps the best documented of any of the “assembly centers.” The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley has digitized and put online JERS records starting in 2011. We draw from their observations in many places in this article.

Poets, Activists, Anthropologists, and Other Prominent Visitors

As with other “assembly centers,” dozens of locals visited Tanforan to see old neighbors and communicate with former business partners. Yet because of its proximity to the Bay Area, several noteworthy individuals visited Tanforan to witness the camp firsthand, including Dorothea Lange, who photographed the camp during its opening days, and anthropologist Margaret Mead. The head of the aforementioned JERS Project, Sociologist Dorothy Swaine Thomas, visited Tanforan on several occasions to meet with her staffers and to collect data as part of the project.

During one of Thomas’s visits with her Japanese American informants, Army officials stepped in, confiscating Thomas’s notes and interrogating her and her Nikkei informants. After this, Thomas and her associates needed written permission by the Wartime Civil Control Administration, which oversaw the forced removal and managed the “assembly centers,” in order to enter the camp. Other blacklisted visitors included actor, activist, and later Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas, who at the time was a member of the Democratic National Committee and an advocate for gender and racial equality. Likewise, racial profiling was commonplace, as the guards paid additional attention to African American visitors.

Perhaps one of the more fascinating visitors at Tanforan was poet Kenneth Rexroth. Later known as the “Father of the Beats,” Rexroth became a leading figure in the San Francisco literary scene, and is often regarded as helping San Francisco develop a literary tradition. A poet with strong leftist convictions, Rexroth and his wife made several trips to Tanforan to support Japanese Americans. Rexroth collected books for the Tanforan library and his wife, Marie Kaas, volunteered as a nurse at the camp’s infirmary. Rexroth also befriended San Francisco activist and YMCA secretary Lincoln Seiichi Kanai. Known for his court case against the West Coast exclusion zone, Kanai engaged in a tour of the Midwest on behalf of Japanese American students with help from Rexroth before his arrest in July 1942.

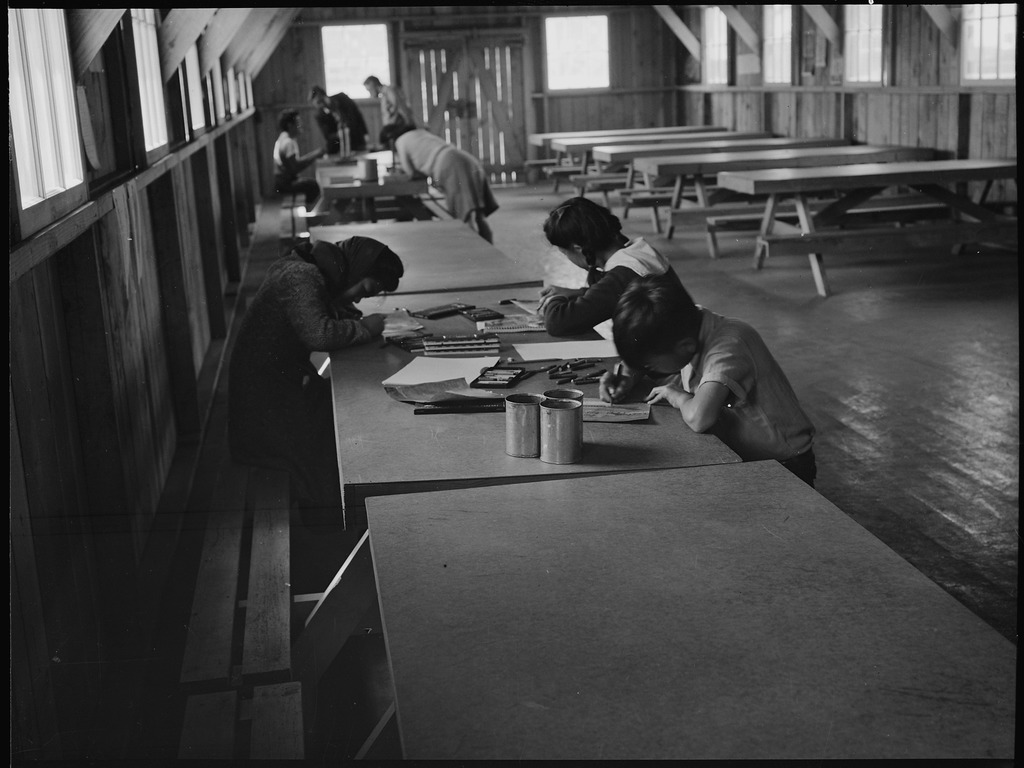

Art and Music Studios

Because of its proximity to the universities of the Bay Area, Tanforan housed an art and music school staffed with professors and students. As previously mentioned in the Densho Catalyst, the Tanforan Art School was run by famed painter Chiura Obata, and notable faculty included artists such as Miné Okubo and Hisako Hibi. Surprisingly, the Tanforan Art school offered more teachers and classes than its later iteration, the Topaz Art School, as many of the instructors left Topaz following the leave clearance program.

Yet less-known is the Tanforan music school and studio. The school was housed in the Tanforan Tavern, a former recreation building for the employees of the Tanforan racetrack. The school was run by Frank Iwanaga, and offered classes in harmony and music history, along with private lessons in piano and violin. By the start of the school, 75 people registered for piano lessons and 25 registered for violin lessons. The school’s first concert was held on June 13, 1942, and featured a variety of piano, violin, and vocal solos featuring the works of Mendelssohn, Chopin, and Debussy. By the time Tanforan closed in September 1942, over 500 students had enrolled at some point in the Tanforan music school.

The Setting for Japanese American Literary Classics

Tanforan figures prominently in several camp memoirs, such as Yoshiko Uchida’s Journey to Topaz and Miné Okubo’s Citizen 13660. Yet there are also works of fiction that are set at Tanforan. Perhaps the most famous example is Toshio Mori’s short story “The Man with the Bulging Pockets.” Originally published in the December 23, 1944 issue of the Pacific Citizen, “The Man with the Bulging Pockets” centers on an elderly Issei man who wanders the camp distributing candy to young children. Gaining a following among the youth at Tanforan for his generosity, the Old Man is nicknamed “Grandpa.” One day, an older Issei bachelor is found also distributing candy, and tells the children to not accept Grandpa’s candy because it is dangerous. When the children reveal the old man’s jealousy towards Grandpa’s popularity, Grandpa responds to the children with grace: “I am not mad because I have many nice friends. He needs nice little friends too, don’t you think?” Although the children listen, Grandpa remains concerned about the divide between him and the old man. Mori concludes the story with an insightful last line: “They should inspire and sing in the oneness of hope, but no. They were partisans, and the split in their circle was the enigma and blot of all mankind.” Mori later republished the story in his 1979 volume The Chauvinist and Other Stories.

Segregated Restrooms for “Colored Gents”

Finally, an observation by the ever-observant Charles Kikuchi:

“I ran across an interesting restroom today. Down by the stables there is an old restroom which says ‘Gents’ on one side and ‘Colored Gents’ on the other! I suppose it was for the use of the stable-boys. To think such a thing is possible in California is surprising. I guess class lines and the eternal striving for status and prestige exists wherever you go, and we are still in need of a great deal of enlightenment.”

That last line remains as true today as it was then.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director, and Jonathan van Harmelen

Jonathan van Harmelen is a Ph.D candidate in History at UC Santa Cruz. He is currently working as a writer for the Densho Catalyst and encyclopedia with support from UC Santa Cruz’s The Humanities Institute.

Konrad Linke’s Densho Encyclopedia article on Tanforan was a key source for this article. Read more here.

[Header image: View of barracks in Tanforan Assembly Center. June 16, 1942. Photo by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]