January 16, 2019

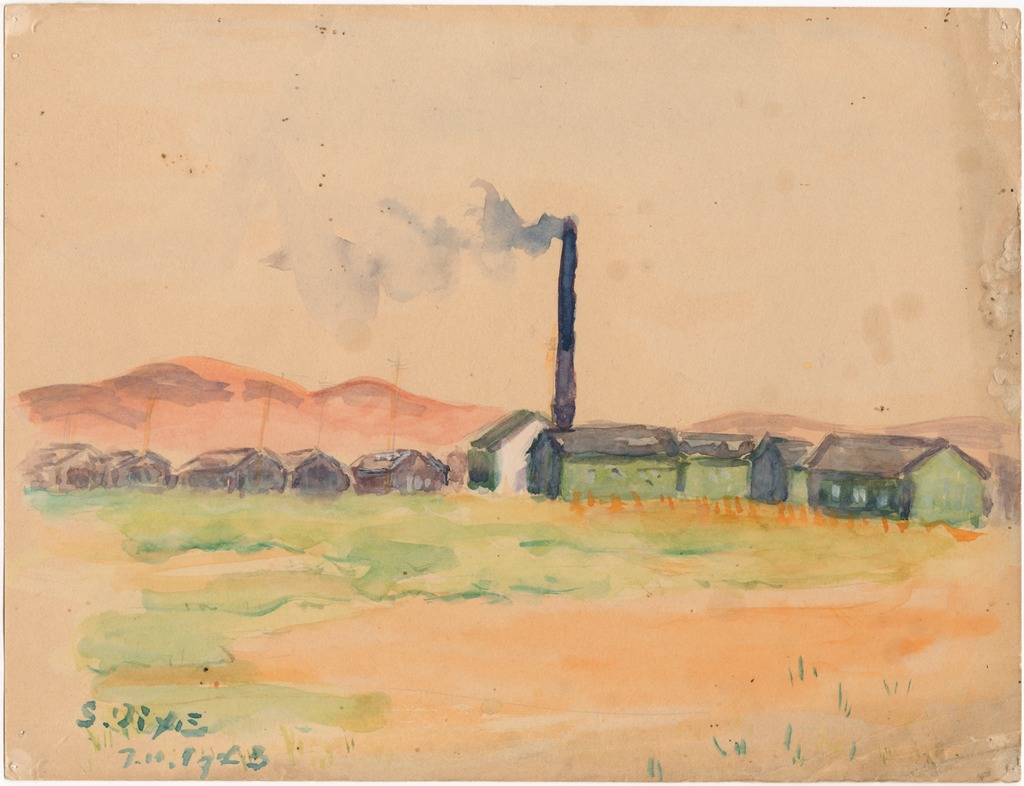

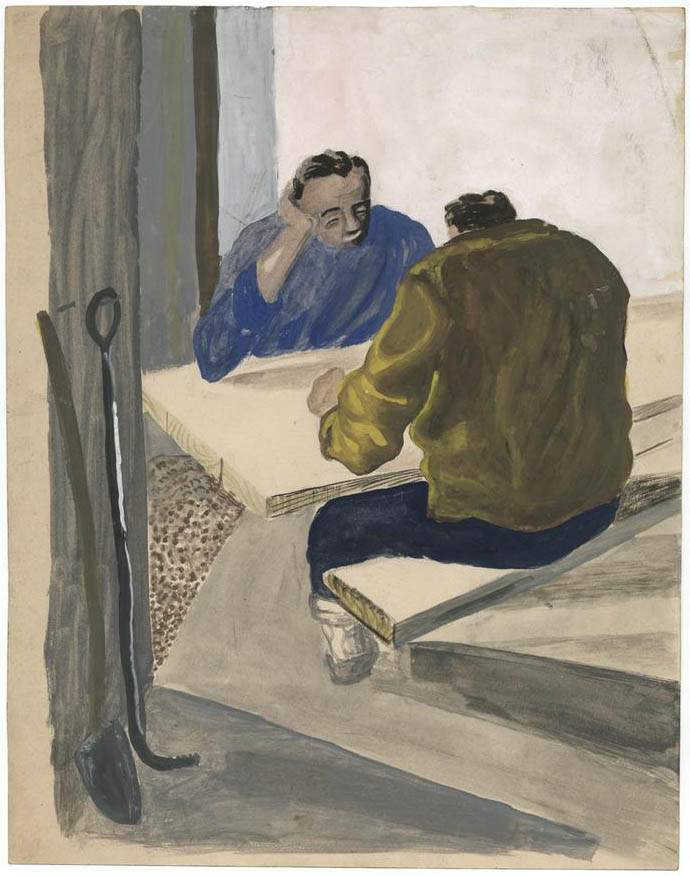

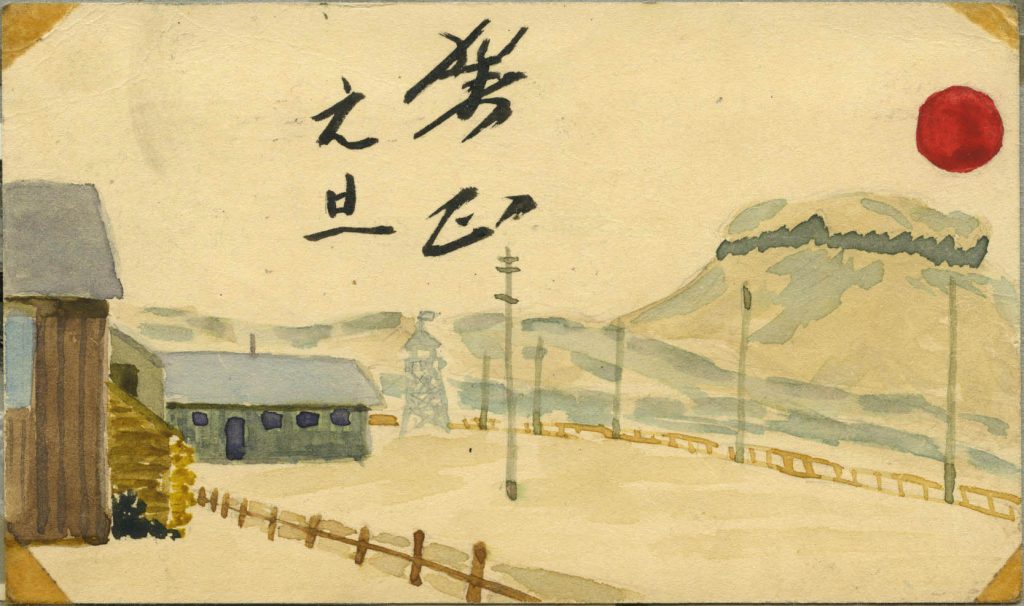

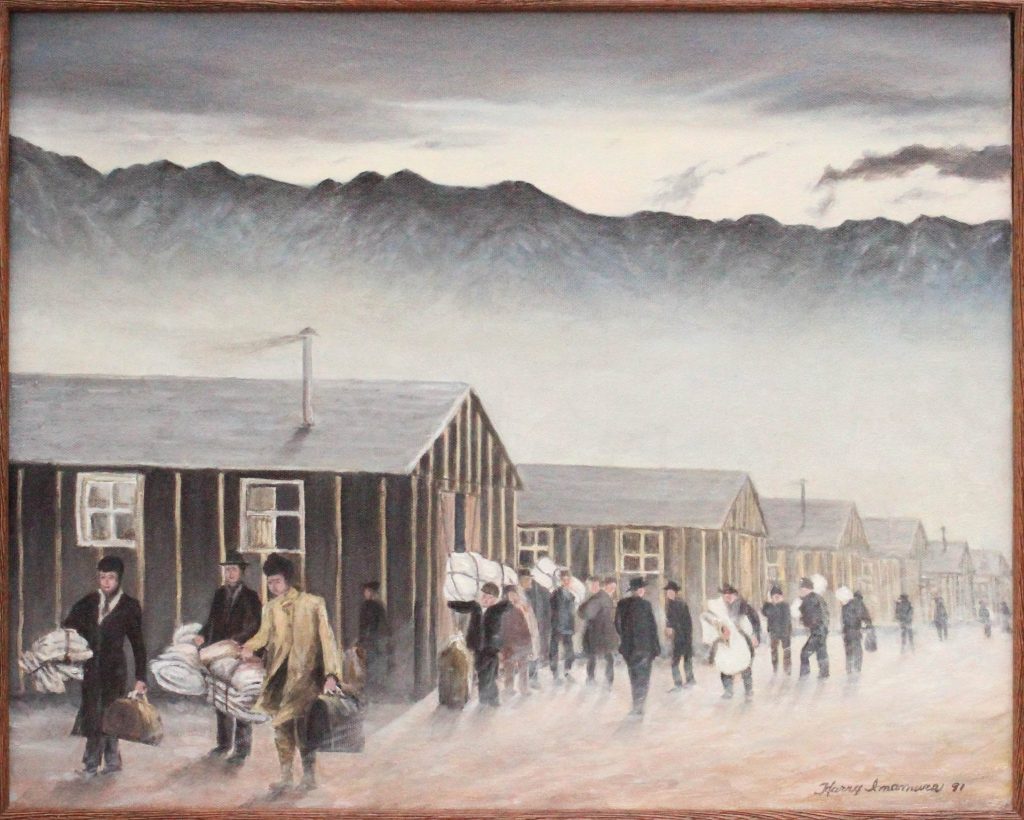

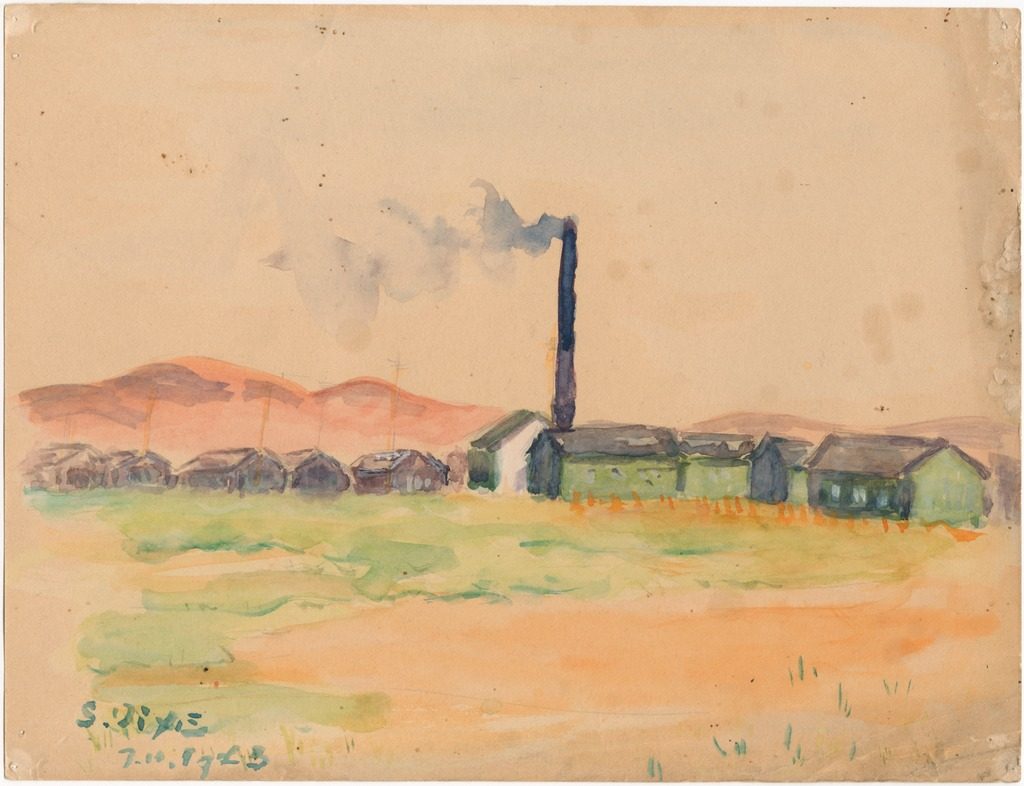

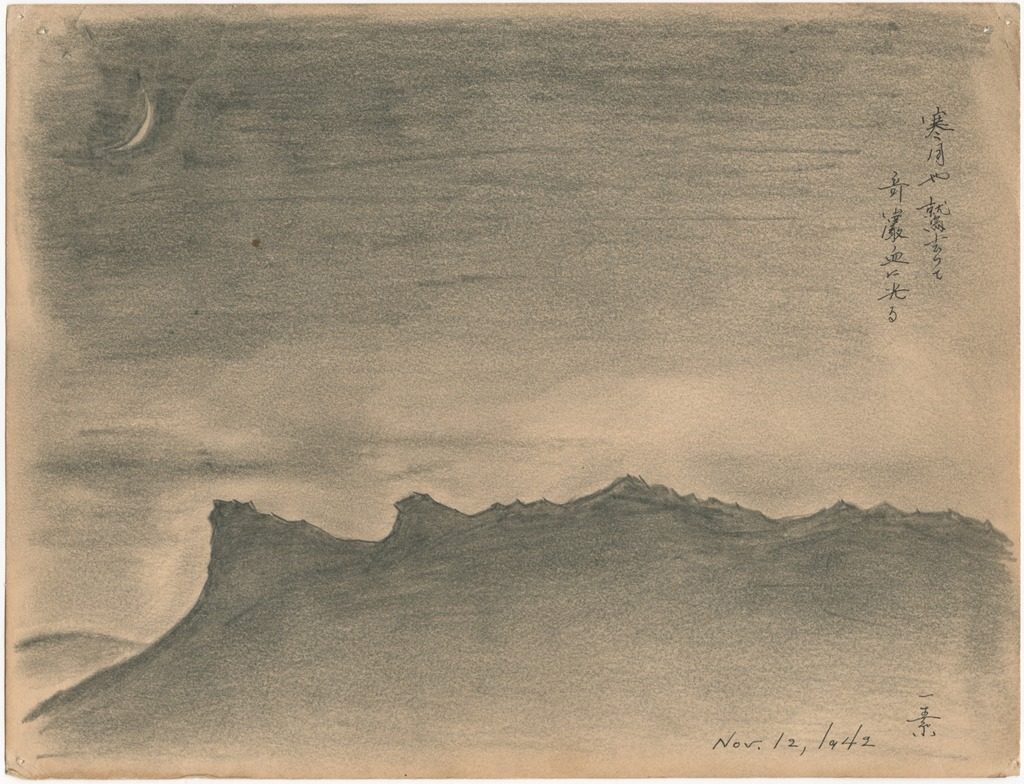

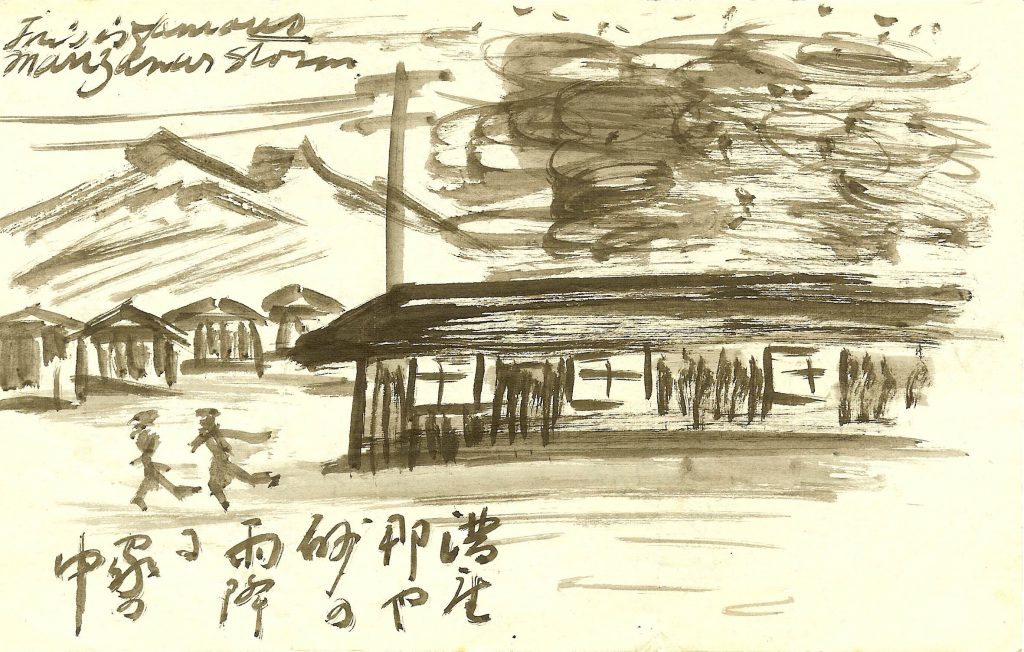

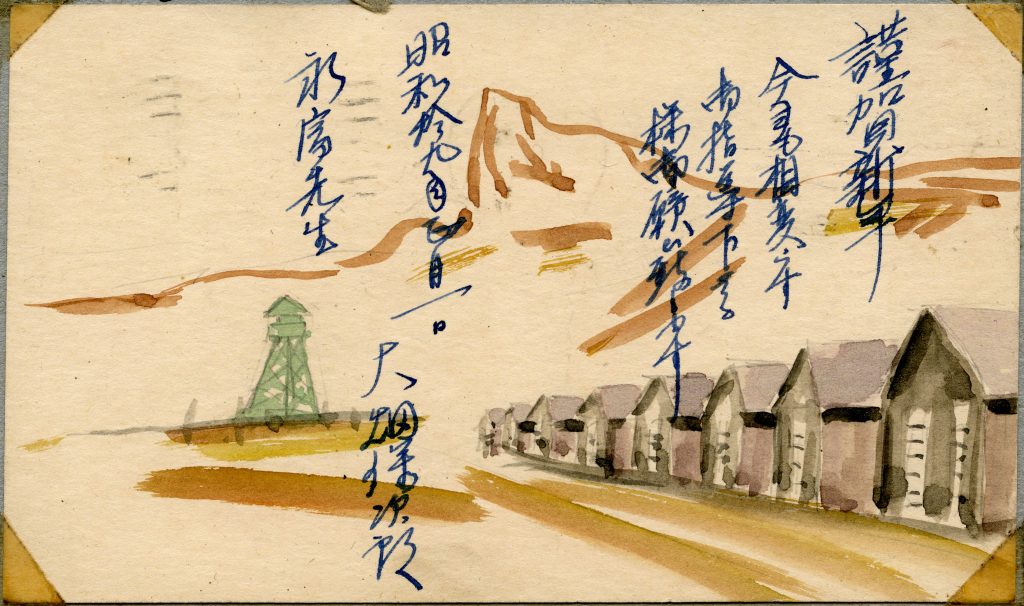

Following the forced exile from the West Coast under Executive Order 9066, many incarcerated Japanese Americans turned to art as a way to cope with their harsh prison environment. Stripped of the routines that had filled their pre-war lives, inmates picked up creative hobbies to while away the idle hours of confinement, and painting and drawing soon became popular pastimes.

At some of the camps, Japanese Americans participated in organized classes in painting and drawing taught by fellow inmates. At Tanforan Assembly Center, for example, professional artists Chiura Obata and George Matsusaburo Hibi established an art school which enrolled more than 300 students in just over five months. After the school’s students and instructors were transferred to Topaz in the fall of 1942, the Tanforan Art Center merged with the Topaz Education Program, growing to over 600 students and offering classes in a wide range of subjects from graphic arts to oil painting.

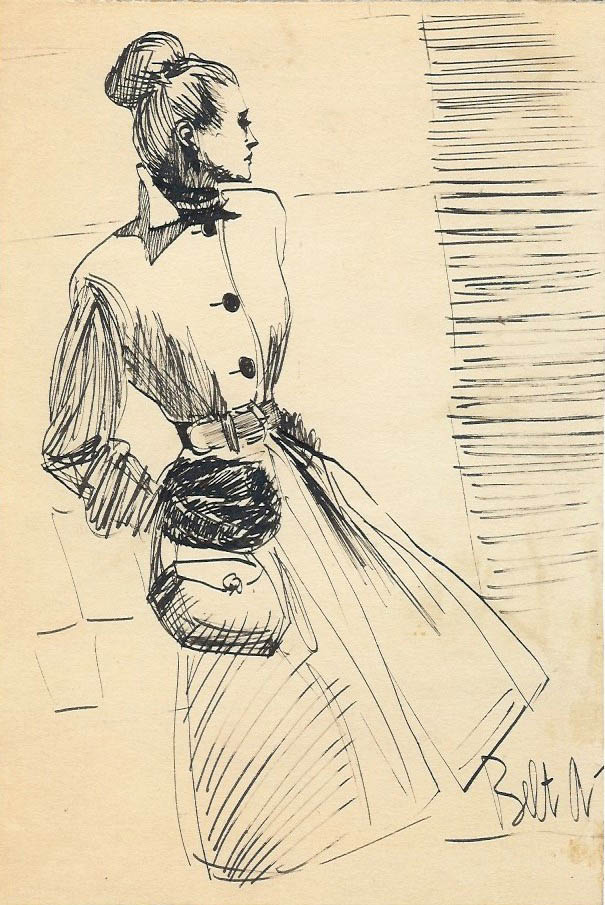

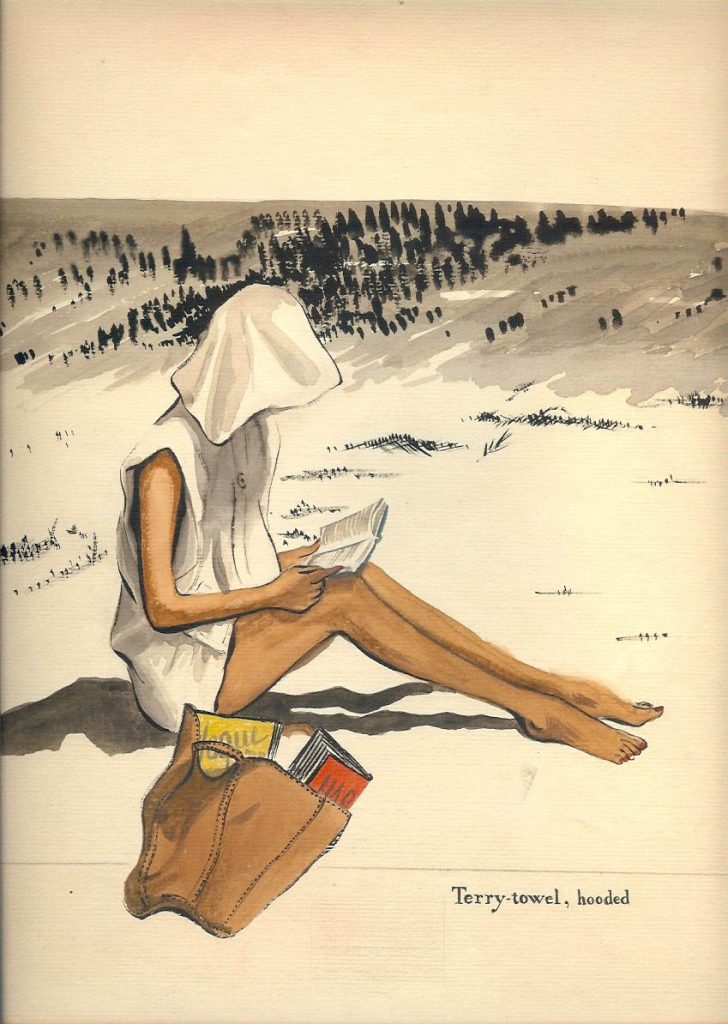

Others tried their hand independently, recreating scenes from the journey to camp, depicting the surrounding landscape and documenting everyday life, and even sketching intricately-detailed fashion designs.

We’re fortunate enough to have several examples of these inmate-artists’ work in our digital archives—and we hope to continue adding to this impressive collection!

Artwork from an Issei art class in Amache, unknown artist. Courtesy of the George Ochikubo Collection.

—

By Densho Staff.

[Header image courtesy of the Shizuko and Shigenori Oiye Collection.