March 18, 2024

In Seattle from the Margins: Exclusion, Erasure, and the Making of a Pacific Coast City historian Megan Asaka examines the erased histories of the communities who built Seattle. In this excerpt, she sheds light on life in the brothels and gambling halls of Seattle’s Tenderloin, a red light district that once operated in today’s Chinatown-International District and Pioneer Square — and how reformist politicians, Japanese government officials, and members of the Japanese American business elite briefly aligned to displace sex workers and other “troublesome” Tenderloin residents.

When the Japanese first started migrating to Seattle in the 1890s, they opened lodging houses in and around the Tenderloin that catered exclusively to Japanese laborers and those newly arrived from Japan. The businesses consisted of “cheap sleeping quarters, using the basements of buildings,” such as the Fujii Hotel on Jackson Street, which charged fifteen cents for “the usual bunk racks.” Chojiro Fujii, the hotel’s owner, would become a leader of Seattle’s Japanese community; he also ran an employment agency on Washington Street. The Great Northern Hotel, located on the corner of Second Avenue South and Jackson Street, also maintained connections with Japanese employment firms. Places like the Fujii and the Great Northern figured centrally in maintaining the system of flexible labor that formed the foundation of the region’s economy. As seasonal industries slowed their operations in the winter, Japanese laborers would return to Seattle and find temporary accommodations in Japanese-run lodging houses and hotels.

As the Tenderloin economy grew, some Japanese hoteliers turned their attention to prostitution. The south end had long been home to commercial sex work, with the lodging house often doubling as a brothel. And Japanese residents became well integrated into this industry as brothel owners, sex workers, and customers. Clustered along King and Jackson Streets, Japanese-owned brothels employed both Japanese and non-Japanese women. Tenderloin inhabitant Kunizo Maeno remembered visiting “a corner… where there were a mixture of Japanese and Irish girls.” Another early Japanese resident recalled “many women… engaged in prostitution.” Among the infamous establishments of the time was the Tokio, a three-story frame building which housed a saloon on the ground floor and seventy-three rooms on the top two floors above. Japanese women who engaged in commercial sex work were, as historian and activist Yuji Ichioka has argued, “among the pioneers of Japanese immigrant society.” Along with employment agencies, brothels formed the foundation of Seattle’s first Japanese district and laid the groundwork for future Japanese involvement in the hotel industry.

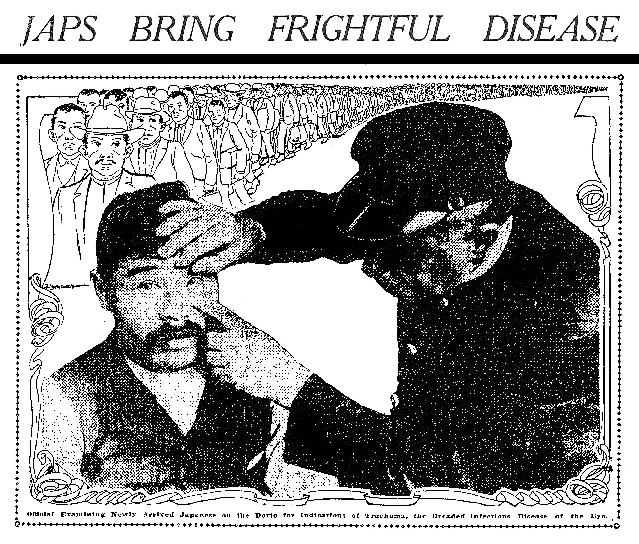

As these businesses grew more visible, though, so too did their reputation as hotbeds of crime, vice, and other illicit activity. In 1905, Japanese proprietors ran forty-two lodging houses south of Yesler Way; by 1909, the number reached seventy-two. Newspaper articles pushed sensational tales of knife fights, brawls, and dead bodies turning up in dark rooms. In 1904 police busted a West Coast burglary ring that “had regular headquarters in a room in a Japanese lodging house in the lower part of the city.” Stories of Japanese smugglers moving drugs and people through a vast network of alleys and inside passageways scandalized the public. “Celestials smuggled across the border and found in Japanese lodging houses,” screamed one newspaper headline. “The Chinese were taken direct from the sloop to the lodging house and have not been seen on the streets.” Health department raids of Japanese hotels further confirmed their unsavory image. Reporting on the arrest of a Japanese hotel proprietor for overcrowding, a local newspaper declared that “almost all cases of contagious maladies when traced to their source are found to come directly… from such surroundings.” The message was clear: Japanese hotels were now “breeding places” for all of the city’s worst problems, a danger to public safety and a threat officials should “purge.”

The unwholesome reputation of Seattle’s Japanese district deeply troubled local Japanese leaders, as well as government officials in Japan. Historian Eiichiro Azuma notes that the Japanese government kept close tabs on its communities around the world, particularly in the United States. Japan had ascended to global power following its victory against Russia in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, which inaugurated a period of Japanese imperial expansion across Asia and the Pacific world. The government viewed its overseas citizenry as representatives of a modern, civilized Japanese empire and monitored their status through a variety of channels, including a network of Japanese associations that had spread throughout the West Coast. Of particular concern were the Japanese laborers who had arrived the decade prior and who lived and worked in Seattle’s south end. Many Japanese officials believed that the workers’ unkempt appearance, disorderly neighborhoods, and unsavory forms of sociability — such as gambling, sex work, and fraternization with Chinese people — fueled nativist claims against the Japanese and, more importantly, endangered Japan’s standing internationally.

In 1908, the Japanese government dispatched a representative, Secretary Masanao Hanihara, to investigate the activities of all Japanese communities along the West Coast. As early as the 1890s, the Japanese consul in Vancouver, BC, had reported on the prostitution and gambling that pervaded Seattle’s Japanese district. Hanihara had already visited Seattle in 1906 and described the Japanese standard of living as “low and unhealthy.” Two years later, he was disappointed to find that little had changed. In a report back to the Japanese government, he summed up the district in one word: “disgusting.” Laborers and small business operators crowded together in “one disorderly section of the city, forming a sort of irregular and indecent Japanese town next to the lower class Chinese.” Other offenses included “shabby houses,” “dubious looking posters,” and “paper lanterns hung shamelessly at doors.” The neighborhood’s layout also disturbed Hanihara. The “backs of houses lead to obscure roads,” he reported, “where at night obscene sights and words are frequently glimpsed.” Overall, he concluded, the district was “indeed far from a community of civilized people.”

Until that point, local Japanese leaders could do little to change the district. Some had even profited handsomely from the Tenderloin’s economy of commercial sex, gambling, and entertainment. But changes were afoot that created an opportunity and an impetus for reform.

In the early 1900s backlash against the Japanese presence along the West Coast reached a fever pitch, mirroring anti-Asian movements against Chinese laborers three decades prior. As the United States government considered a similar exclusion law, Japan intervened. Concerned that its citizens overseas were being subjected to the same treatment as the Chinese, Japan entered into a series of diplomatic negotiations from 1907 to 1908 known as the Gentlemen’s Agreement. Japan agreed to stop issuing passports to laborers bound for the United States in exchange for the city of San Francisco allowing Japanese students to attend public schools, from which they had been banned. While the agreement resembled previous anti-Chinese exclusion laws, there was one key difference. Eager to appease Japan, now a global power, President Theodore Roosevelt agreed to allow Japanese women to reunite with their husbands in the United States. As the migration of Japanese male laborers declined, in their place rose a Japanese middle class populated by married couples and families with children.

With the arrival of women and families, Japanese leaders began to think seriously about changing the conditions of their neighborhood. And here, the city’s plan for the Tenderloin created an opening for them. As part of his promise to clean up the city, [Mayor George] Dilling began to target Tenderloin lodging houses, going block by block to order upgrades and vacate residents. On February 10, 1912, the fire department declared the entire block from 73 to 85 Yesler Way “unsafe to human life” and ordered all buildings vacated. Over the next three days, inspectors temporarily closed the Seattle Hotel on Jackson Street and permanently shut down a basement lodging house on First Avenue South and Main Street because of the “insufficiency of exits, the arrangement of the rooms and passageways, the lack of ventilation, the condition of the wooden floors, and the lack of light.” Two days after that, inspectors targeted the 400 block of Yesler Way, vacating the basements, while allowing the top floors to remain open if owners installed fire escapes and replaced wooden floors with concrete. By the end of 1912, fire and building inspectors had vacated or ordered significant upgrades to twenty-four buildings in Seattle’s south end.

Japanese leaders accepted these actions, in part because they weren’t targeted. The initial inspections and mandatory upgrades involved the property owners, not the lessees or business owners operating within the buildings. At the time, Japanese community members did not own many of the buildings and so viewed the closures, upgrades, and improved safety measures as a welcome development. They even began to actively participate in the city’s crackdown on the Tenderloin. The Japanese Association of North America, together with the Japanese consul in Seattle, supplied US federal immigration authorities with the names of brothel owners, gamblers, and Japanese women working (or thought to be working) as prostitutes. Though it’s unclear if the immigration officials ever responded, these actions on the part of Seattle’s Japanese leadership reflected a desire to rid the community of those they considered troublesome, which aligned with the city’s own agenda within the Tenderloin.

—

Megan Asaka is an award-winning scholar, writer, and teacher of Asian American history, urban history, and public humanities. She worked as an oral historian and archivist at Densho from 2004-2009, and is now an associate professor of history at the University of California, Riverside and lives in Pasadena.

This is an excerpt of Seattle from the Margins: Exclusion, Erasure, and the Making of a Pacific Coast City, published by University of Washington Press, 2022.

[Header: A Japanese-owned hotel located on Yesler Avenue in Seattle’s Nihonmachi or Japantown, 1913. Courtesy of the Tamura Family Collection.]