July 8, 2025

In this excerpt adapted from her new narrative history, Together in Manzanar: The True Story of a Japanese Jewish Family in an American Concentration Camp, Tracy Slater delves into the complicated, and quite often contradictory, government policies that dictated the lives of mixed-marriage families and multi-racial Japanese Americans inside America’s WWII concentration camps.

Join Tracy and Densho’s Brian Niiya for a conversation about the book and the history behind it on Tuesday, July 15.

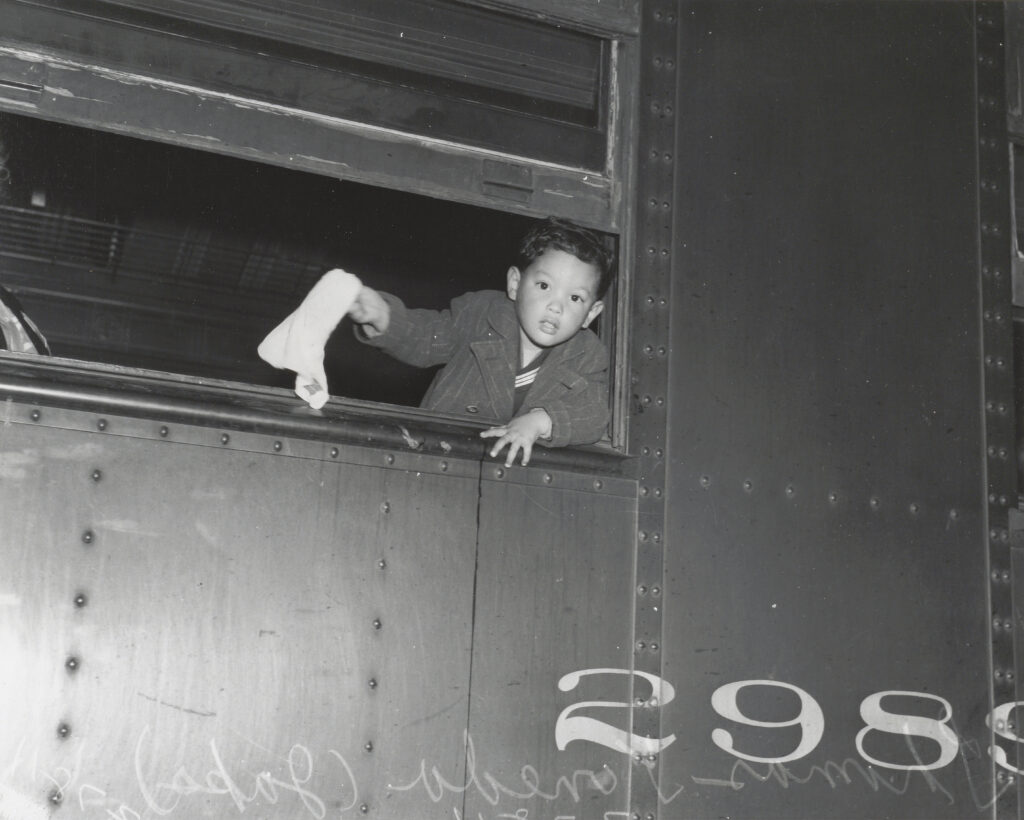

Just past dawn on March 30, 1942, Elaine Buchman Yoneda stood on a Los Angeles sidewalk, unsure where to turn. She looked up at the building before her, solid concrete and stretching half a block: the South Spring Street civil control station, where she’d been ordered to bring her three-year-old son, Tommy, for deportation to a concentration camp.

Elaine was the daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants and the wife of a Japanese American man. Her husband, Karl, had gone to Manzanar a week earlier. Before the war, the Yonedas had been among the West Coast’s most prominent leftist activists. Now, Karl was one of the first Japanese Americans in a camp that would eventually hold 10,000, the majority US citizens, who’d been forced to relocate off the coast and imprisoned en masse. As for Elaine’s son, it was him the army wanted now, she’d been told over the phone the night before. Not you, the priest had explained. Not if you’re white, he meant—even though she’d given birth to a half-Japanese child.

The clergyman was from the Maryknoll mission, a Roman Catholic order that had long worked with the Japanese American community and was now assisting with their removal from the West Coast. Alien or citizen, healthy or sick, loyal or lost: all had to go. But as for Elaine, “Oh, you don’t have to go; you don’t have to go,” he’d said as she’d clutched the handset in her parents’ apartment the previous evening, the darkness shrouding their home in the Jewish enclave of Boyle Heights.

Nor will you be allowed to, he’d suggested.

Her son was a different story. The three-year-old, like anyone along the West Coast with even “the slightest amount of Japanese blood,” was to be rounded up—“evacuated,” US army officials called it—and sent to a camp. But if anyone believed Elaine was just going to surrender her child, well then they really knew from nothing.

Despite Elaine’s determination to protect her son, joining him behind barbed wire would not shield her family as a whole. If she went to Manzanar with Tommy, she’d have to leave behind Joyce, her white daughter from her first marriage.

“Soliciting the Privilege” of Incarceration

In San Francisco that spring, the man who’d ordered Tommy’s detention in the desert, Karl R. Bendetsen, was confronting his own dilemmas. As head of the Wartime Civilian Control Administration (WCCA), his job of overseeing the removal of anyone on the West Coast with “even one drop of Japanese blood,” as he himself reportedly put it, amounted to a seven-day work week. It was, in his own words, a “most trying” assignment. And yet, he admitted in a letter to a colleague, “the challenge presented made it a problem of such absorbing interest that I would scarcely wish to have traded the experience.”

Despite his enthusiasm and thorough planning, Bendetsen had struggled since early spring with an unforeseen consequence of incarcerating an entire population. His quandary had arisen on the very day Elaine brought Tommy to the South Spring Street civil control station to register for entrainment to Manzanar. Since then, reports had been coming from control stations up and down the West Coast about a contradiction in Bendetsen’s carefully crafted “evacuation” plan.

When the WCCA announced the forced removal and incarceration of the West Coast Japanese American community, they mandated that having any Japanese ancestry at all targeted one for imprisonment. One official document clarified that “the slightest amount of Japanese blood was sufficient to impose liability.” But WCCA officials also repeatedly insisted that, as evidence of America’s democratic nature and humane practices, their procedures were meant to keep families together, incarcerated (“evacuated”) as a group to one or another of the concentration camps (“assembly” and “relocation centers”). In the case of mixed families like the Yonedas, WCCA workers were stumped.

Initially, the task of categorizing and organizing mixed-family members fell mostly to social workers at the control stations, on temporary assignment for the WCCA. They made ad hoc decisions about which families should or could be sent away en masse, who among them could be exempted from removal and incarceration, and what to do about non-Japanese people facing separation from their Japanese (or mixed-Japanese) spouses and children.

For much of the spring, control station staff relied on a document called the Temporary Exemption Certificate for Mixed-Race Family Groups. This form allowed families to apply to WCCA headquarters for permission to remain free and home together. But on May 8, 1942, Bendetsen’s boss—the head of the Western Defense Command (WDC), General John DeWitt—officially cancelled and retroactively revoked all temporary exemptions for mixed-marriage families.

Instead, DeWitt announced, “the non-Japanese spouse of a person of Japanese ancestry or the non-Japanese parent of a part Japanese child may elect to accompany his or her Japanese ancestry spouse or child into an assembly or reception center.” But there was a caveat: the non- Japanese mother, father, wife, or husband now had to sign a “Request and Waiver of Non- Excluded Persons,” or WDC Form PM-7.

“Know All Men by These Presents,” the document opened with archaic flourish, “the undersigned does hereby request the privilege of accompanying” their child or spouse to be imprisoned, “in all respects as if he or she were a person of Japanese ancestry.” Becoming “as if Japanese” meant that once in camp, the person became a prisoner. Change your ethnic category, change your eligibility for freedom. At bottom appeared a line for the “Signature of Voluntary Evacuee,” whereby a spouse or parent was to “expressly represent and agree” that they had “personally solicited the privilege” of joining their loved one behind barbed wire, “without persuasion” or “duress.”

“A Complicated Matrix of Racial and Gender Categories”

Despite this official pretense that everyone in camp was Japanese (or “as if Japanese”), it became clear to all involved that throughout spring and summer 1942, a growing population of mixed-race and non-Japanese people had been sent to one or another of the camps for Japanese Americans. By that summer, an estimated 2,100 people in mixed-race families had been incarcerated. For Bendetsen in particular, such an ethnically heterogenous population presented a troubling ambiguity. So he devised a plan to measure the Japanese-ness of any particular mixed family who might want to leave lockup.

In early July, preparing to implement such a plan, Bendetsen sent a letter from his office in San Francisco to a Colonel Ralph Tate in the Washington, DC, office of the assistant secretary of war. “My dear Colonel,” the letter began before reporting that all “Center Managers have been directed to report mixed marriages and mixed blood cases.” Bendetsen claimed that for families with white or mixed-white members, “their Americanization and their awkward social position” was making “life in the Japanese Centers… a trying and often humiliating experience.” (As for the trying and often humiliating experiences of the other incarcerees, Bendetsen only noted that the mixed families’ “presence in the Assembly Centers was the source of constant irritation to the Japanese, provoked bad feeling and added to the difficulties of administration.”)

Bendetsen’s boss, General DeWitt, came at the problem from a slightly different angle. According to him, a new plan was needed for “protecting mixed-blood children from a Japanese environment”—or, as another government official put it, isolating them from “infectious Japanese thought.”

This time, Bendetsen’s solution materialized in a document alternately called the Mixed-Blood or the Mixed-Marriage Policy. This policy, announced on July 3, 1942, created a complicated matrix of racial and gender categories to delineate who should remain behind barbed wire, who might be eligible for freedom from the camps, and who among this latter group could return home to the West Coast, or alternately must remain exiled from there, allowed only to resettle beyond the restricted area (east of Arizona, Idaho, Montana, or Utah).

The policy’s first iteration mandated that a Japanese or Japanese American man and his white wife and “unemancipated” mixed children could be eligible for freedom only if they did not return to the West Coast. A white American man could be released and return home with his Japanese or Japanese American wife if they had young mixed children with them in camp and if the so-called “environment of the family” was “Caucasian.” Otherwise, they would have to resettle outside the restricted area, separate from each other while he returned home alone, or remain imprisoned.

Adult “individuals of mixed blood” who were citizens of the United States could be eligible for release and return to the West Coast if they too could prove that their “home environment has been ‘Caucasian,’” or at least had been before they were incarcerated. Otherwise, they also would have to resettle east or remain imprisoned. As for spouses in mixed marriages without unemancipated children, they had no recourse at all under the mixed-marriage policy unless married to someone serving in the US Armed Forces. In this case, the childless woman could be freed only if she agreed not to go home and resettled east.

If an applicant or family met one of these criteria, they would be vetted by the government, and the next stage of Bendetsen’s plan began. Applicants had to pass army intelligence and FBI background checks, provide proof of either a job or other financial support outside camp, and gain approval from the sheriff or local police chief at their intended destination. Anyone lucky enough to leave camp did so with an order to report every month to an army station near their intended residence, where they would submit documentation of any family births, deaths, marriages, divorces, changes of address, “or any incident bearing upon community acceptance” — i.e., objections to their presence outside camp.

Throughout that summer and beyond, the policy’s rules of eligibility created much confusion. Camp administrators were initially stymied by the sole focus on multiethnic families of Japanese and European heritage, because many mixed families actually had no members who counted as “white” to officials. How to handle Chinese, Mexican, Indian, and Filipino husbands— spouses who would not be identified as white but were citizens of “friendly” (or US-colonized) territories? And just what was a “Caucasian environment” anyway? Some thought it depended on the kind of food a family had eaten for dinner before the war, others on the friends who visited them at home.

But often, camp administrators simply deferred to the equally vague category of appearance, as in the case of a woman named Mitsuko Komuro Ramos. She was wife of a US-army enlistee stationed in San Luis Obispo with the First Filipino Infantry Battalion of the US Army. Ramos had been forced to leave her home in Santa Barbara and then incarcerated in Tulare Assembly Center. She applied for release in the summer of 1942. But Ramos had no children, so she knew returning to California, where her husband was stationed, would be prohibited. Instead, she applied to leave camp after securing a job offer as a maid in Illinois. Though she was ethnically Japanese and had been born in Japan, her file compiled by WCCA staff noted, in favor of her application, that she did “not appear to be Japanese” at all, having “facial characteristics more nearly typifying persons of Spanish descent,” as if she had somehow acquired the ethnic appearance of the Europeans who had once colonized her husband’s homeland.

Beginning in late July 1942, in an apparent attempt to resolve some of this confusion, a new version of the mixed-marriage policy appeared. It offered an expanded category of husbands eligible for release with their Japanese American wives. Once including only “Caucasians,” this group grew to encompass the many cases of non-Japanese but also non-white American men, as well as Hispanic Americans and those who were citizens of friendly or Allied-colonized nations (China, the Philippines, Mexico, India). These men could now leave camp with their spouses as long as they had unemancipated children incarcerated with them and agreed to resettle east. A later iteration of the policy eventually stipulated that even a white woman who had “sired” mixed children with a Japanese American man could be eligible to return to the West Coast with her young offspring—but only if her husband were “dead or long since separated” from the family. By October 1942, requirements for freedom for single, mixed-race adults had also changed. As one official explained, any American “whose non-Japanese blood exceeds Japanese blood” might now be eligible to live on the West Coast.

A “Caucasian” home environment made no difference for six-year-old Richard Honda that fall, however. The young boy had been incarcerated all alone in Manzanar. Well before the war, at the age of four months, Richard Honda had been adopted by a white family in California named the Spandrios, after his Japanese biological mother’s death. Five years later, the boy was forcibly removed from his family and placed in Manzanar’s “Children’s Village,” the only orphanage among the camps. According to an official memo, “The Spandrio family asked to have him returned and claimed that the community would accept the child wholeheartedly.” The response arrived on November 13, 1942: “The request for the release of Richard Honda, a person of Japanese ancestry, age six years, to residing [sic] in Military Area No. 1 is disapproved.”

Together in Manzanar—At a Cost

As for the Yonedas, after officials failed to stop Elaine from boarding the train with Tommy in the spring of 1942, she became the only Jewish woman in government records of incarcerees in the camps for Japanese Americans, her son the only mixed Japanese Jewish prisoner. But she was far from the only white wife. Among the in-camp population were at least 134 non-Japanese people, officially categorized as either “Caucasian” or “other” (despite somehow also having been designated “as if of Japanese ancestry”). These included 63 white wives; eight white husbands; eight “other” husbands; 31 “other” wives; and three white women who were separated or divorced from their Japanese or Japanese American husbands but who wanted to stay with their incarcerated children.

Nor was Elaine the only mother the government separated from family members—or even her own child. As one of approximately 2,100 incarcerated people in mixed families, she was among a population who left behind many non-Japanese relatives. Her fourteen-year-old white daughter, Joyce, was one of untold thousands who remained outside of camp, only to endure the trauma of long-term and sometimes permanent separation. For the Yonedas, once Elaine stepped behind Manzanar’s barbed wire, Joyce would never live with her again.

—

Adapted from Together in Manzanar: The True Story of a Japanese Jewish Family in an American Concentration Camp, by Tracy Slater, available now from Chicago Review Press.

Tracy Slater is a Jewish American writer from Boston, based in her husband’s country of Japan. Her first book, the mixed-marriage memoir The Good Shufu: Finding Love, Self, and Home on the Far Side of the World (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2015) was named a Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers selection and one of PopSugar’s best books of 2015. Her second book is the forthcoming work of narrative history titled Together in Manzanar: The True Story of a Japanese Jewish Family in an American Concentration Camp (Chicago Review Press, July 8 2025). Slater has published work in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, Time magazine’s Made by History, and more. She taught writing for over ten years in Boston-area universities and in men’s and women’s prisons throughout Massachusetts. She is the recipient of PEN New England’s Friend to Writers Award and holds a PhD in English and American literature from Brandeis University.