January 22, 2026

In what has become an annual tradition, Densho Content Director Brian Niiya starts the new year by looking at the lives of notable Nisei who would have turned 100 in 2026.

Those born in 1926 were typically in high school when World War II began, and were thus incarcerated as teenagers and generally graduated high school in a concentration camp. Several were able to leave camp early to attend college, while others joined the army, though most in this age group didn’t see combat and ended up serving after the war had ended. Nonetheless, the war was a turning point for nearly all of their lives.

Most of the Nisei featured in this post became known for their role in keeping the story of the wartime incarceration alive, though there are also prominent artists, political leaders, and others. This edition may have a record number of people who will live to see their 100th birthdays! As always, I use the term “Nisei” loosely and even include a couple of notable non-Japanese Americans who were key figures in the Redress Movement.

Literary Figures

We’ll start with two idiosyncratic literary figures associated with the San Francisco Bay Area and its Beat poetry scene of the 50s and 60s. Born and raised in Los Angeles, Albert Fairchild Saijo (Feb. 4, 1926–June 2, 2011) and his family were incarcerated at Pomona and Heart Mountain, where he was editor of his high school newspaper and wrote for the Heart Mountain Sentinel. After a stint in the 442nd, where he served in post-war Italy, he attended USC on the G.I. Bill, graduating with an international relations degree and starting graduate study. After dropping out and venturing to San Francisco, he fell in with a group of writers and intellectuals interested in Zen Buddhism and other tenets of Asian philosophy, as well as Beat poets/writers such as Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Gary Snyder. He later settled in Marin County, the Lost Coast of California, and the Big Island of Hawai`i. His books include The Backpacker (1977), Outspeaks: A Rhapsody (1997), and Trip Trap: Haiku on the Road with Jack Kerouac and Lew Welch (1973).

Shigeyoshi Murao (Dec. 8, 1926–Oct. 18, 1999) was another Nisei veteran who found his way to San Francisco in the 1950s. Born and raised in Seattle and incarcerated at Puyallup and Minidoka, Murao joined the Military Intelligence Service and served in postwar Japan. While working at a bar, he met Peter Martin, a sociologist who had started City Lights bookstore, and was eventually offered a job there. Murao later became the manager and co-owner of City Lights, which would become the center of the Beat movement and fixture of the city’s literary scene for decades. Murao was famously arrested in 1957 for selling Allen Ginsberg Howl and Other Poems that led to a landmark ruling that the book had literary value, thus not pornographic, and was protected under the First Amendment. Murao remained at City Lights until health problems—and a dispute with co-owner Lawrence Ferlinghetti—led to his leaving the store. Beyond his work in building City Lights, Murao self-published Shig’s Review, an experimental xeroxed art zine from the 1960s to the 1990s.

Keeping the Story Alive

The next group includes five Nisei who have played important roles in telling the story of Japanese American and/or incarceration history. I had the pleasure of knowing four of the five to varying degrees.

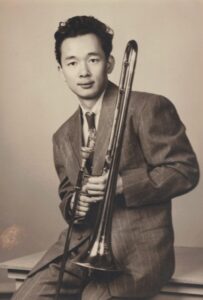

My first job out of graduate school in the late 1980s was at the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) in the days before it opened to the public. Bruce Kaji (May 9, 1926–Oct. 26, 2017) and Jim Hirabayashi were key figures in the early history of JANM. Born and raised in Los Angeles, Kaji was incarcerated with his family during World War II and served in the MIS in post-war Asia. After getting his accounting degree from USC, he started an accounting firm and was one of the founders of Merit Savings & Loan, while also serving as the treasurer of Gardena, his adopted home. Kaji was a key figure in the development of Town & Country shopping center in Gardena and other business ventures. But he is likely best remembered today as one of the founders of the JANM and was its initial board president. Unlike many of the other board members, he had a genuine interest in Japanese American history and spoke often about the impact of his Manzanar years, where, among other things, he played the trumpet in the Jive Bombers dance band. In 2010, he published his memoir, Jive Bomber: A Sentimental Journey.

Jim Hirabayashi (Oct. 30, 1926–May 23, 2012) was an anthropologist who played a key role in the founding of Asian American Studies in the 1960s and 1970s, and was JANM’s initial chief curator in the late 1980s and 1990s. Born and raised in Washington state, Hirabayashi and most of his family were incarcerated at Pinedale and Tule Lake. Famously, his older brother Gordon refused to obey curfew and exclusion orders in order to challenge them in court. After the war, he attended the University of Washington and went on to earn a Ph.D. at Harvard, doing his field work in Japan. He was hired at San Francisco State University in 1959, the second Japanese American faculty member hired there after S.I. Hayakawa. A decade later, the two would find themselves on opposite sides of the Third World Liberation Strike at the college: Hayakawa, as university president, opposed the student strikers, while Hirabayashi marched with them. Hirabayashi would eventually serve as the first chair of the college’s Asian American Studies program and later as the dean of the Ethnic Studies Department. After retiring from SF State, he took on the curatorial role at JANM, where he helped establish the museum’s approaches to collections and exhibitions. As a young staff person at JANM, I worked under him and remember him as a kind and supportive mentor who valued what us youngsters had to say and treated everyone with respect and good humor.

Like Hirabayashi, Harry H.L. Kitano (Feb. 14, 1926–Oct. 19, 2002) was a pioneering academic whose work was shaped by his wartime incarceration. Born and raised in San Francisco, he and his family were incarcerated at Santa Anita and Topaz. Leaving camp in 1944 to take a job in Wisconsin, he subsequently pursued a career as a musician, playing in a number of big bands that toured the Midwest. Given the anti-Japanese tenor of the times, he took on a Chinese stage name, Harry Lee, something that other Nisei performers of the time also did. He returned to California in 1946 to attend the University of California, Berkeley, eventually attaining a Ph.D. in 1958. He was hired as a professor at UCLA in the social welfare and sociology departments that same year. He was a key if unsung figure in the founding of Asian American Studies at UCLA and was an early director of the Asian American Studies Center. In 1967, he and his friend and colleague Roger Daniels hosted the first academic conference on the wartime incarceration, and Kitano’s 1969 monograph, Japanese Americans: The Evolution of a Subculture, blended sociological methods with his own experience to become an influential and widely cited work. With Daniels and Sandra Taylor, Kitano hosted another conference on camp and redress in 1983 that led to the anthology Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress. In 1999, he co-authored with Mitchell T. Maki and S. Megan Berthold, Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress in 1999, one of the first studies of the Redress Movement. In all, he spent thirty-six years at UCLA and remained active in the community until his passing in 2002.

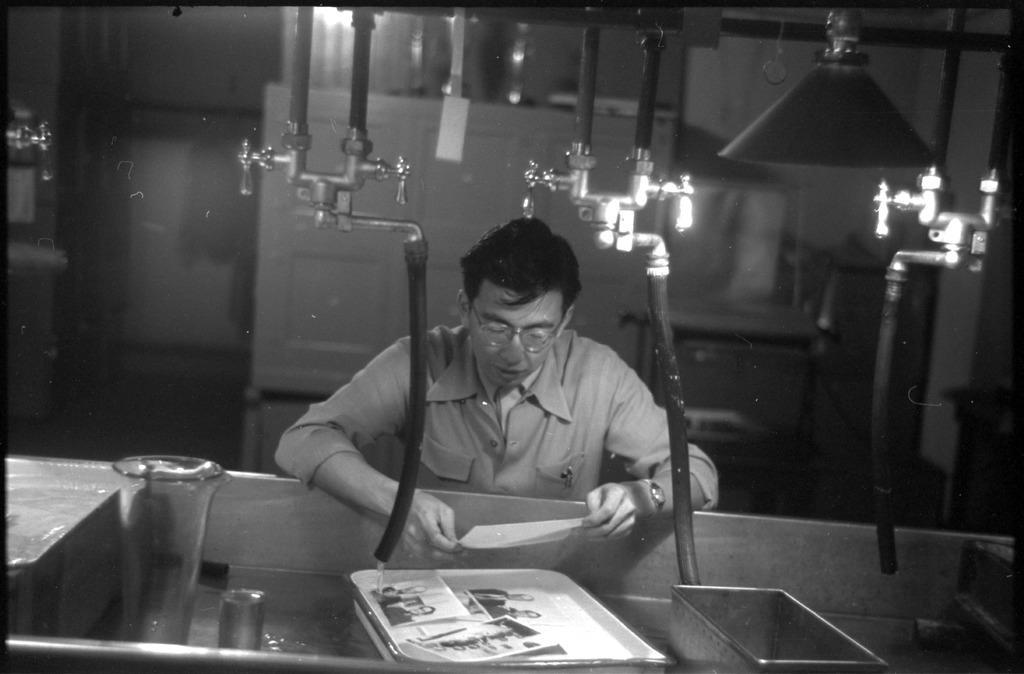

Frank C. Hirahara (Apr. 19, 1926–Feb. 7, 2006) was an amateur photographer who documented life at Heart Mountain and the postwar Japanese American community in Portland, Oregon. Born and raised in Yakima, Washington, Hirahara and his family were incarcerated at Portland and Heart Mountain. As at other camps, photography by incarcerees was initially banned for the first year or so, at which point Frank and his Issei father George purchased photographic equipment from the Sears, Roebuck and Co. catalog and began taking photographs of life at the camp. As a high school student, Frank shot photographs for the high school yearbook. After leaving Heart Mountain in July of 1944, Frank attended Washington State University, graduating in 1948 with an electrical engineering degree and settling in Portland, where he took hundreds of photographs of Japanese American community life there. He moved to Anaheim in 1955 and worked for Rockwell International until 1988. Some 2,000 of George and Frank’s Heart Mountain photographs are at Washington State University, while over 1,500 of Frank’s Portland photographs are at the Japanese American Museum of Oregon and also accessible through Densho’s Digital Repository. These two collections provide unique views of life in camp from the perspective of a high school student and of early post-war community life.

Despite her lack of formal academic training, Michi Nishiura Weglyn (Nov. 29, 1926–Apr. 25, 1999) wrote one of the most important and influential books on the Japanese American incarceration. Born in Stockton and raised on a family farm in Brentwood, California, she and her family were incarcerated at Turlock and Gila River, graduating from Butte High School at the latter in 1944. Aided by the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, she attended Mt. Holyoke College in Massachusetts but had to withdraw after contracting tuberculosis, a malady that would recur throughout her life. She eventually settled in New York City and became an acclaimed costume designer in the 50s and 60s, most notably for the Perry Como Show, for which she also appeared regularly on screen. Inspired by the Civil Rights Movement and by her own wartime experiences, she spent years in the National Archives and other repositories, conducting research on the Japanese American incarceration, eventually publishing Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps in 1976. While there had been other academic works on the incarceration, Weglyn’s was the first by a Japanese American, and an angry Japanese American at that. Appearing at a key moment as the push for redress and reparations was ramping up, Years of Infamy, inspired many to action. Weglyn remained in New York for the rest of her life, active in the Redress Movement and in the subsequent push to secure redress for groups that had been initially denied. I got to know her a bit in the late 1980s and remember her as elegant and forceful on the one hand, but unfailingly kind and generous on the other, whose praise for one of my first published pieces meant a great deal to a young writer.

Redress

As the Redress Movement recedes into the past, it remains important to recognize key figures in those historic events, including two non-Japanese Americans who were important figures in the story.

Joan Z. “Jodie” Bernstein (Mar. 17, 1926) was a lawyer and chairperson of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). Born Joan Zeldes in Illinois, the eldest child of Jewish immigrants, she graduated from the University of Wisconsin in 1948 and Yale Law School in 1951. Despite the fact that many law firms at that time didn’t hire women or Jews, she managed to land positions with mainstream firms in New York and Chicago. After moving to Washington, D.C., when her physician husband, Lionel Bernstein, took a position with the Veterans Administration, Jodie re-entered the work force after thirteen years as a stay-at-home mother, eventually landing a position in the Bureau of Consumer Protection of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and later working for the Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. While at her last job, she was appointed to the CWRIC by President Jimmy Carter. She was the only woman commissioner, and was elected as chair by her peers. In that position, she oversaw the hiring of staff, chaired the 1981 hearings in all locations except for California, and became a supporter of monetary compensation for incarcerated Japanese Americans. After a stint in the private sector, she was appointed director of the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection in 1995 before retiring in 2001.

It is generally accepted that redress would not have happened without the support of African American legislators, and as the chair of the Congressional Black Caucus during the time redress legislation was being considered, Mervyn Dymally (May 12, 1926 –Oct. 7, 2012) may have been the most important figure in garnering that support. Born and raised in Trinidad of African and South Asian descent, Dymally came to the U.S. for college and eventually began a political career that saw him first elected to the California State Assembly in 1962, then later to the state senate as California’s lieutenant governor. In 1980, he was elected to Congress in 1980, representing a South Los Angeles County district that included Gardena and Torrance, areas heavily populated with Japanese Americans. Long cognizant of the Japanese American incarceration story, he was an early supporter of redress, introducing early redress bills in 1982 at the behest of the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations (NCRR). Later, he wrangled support for what would become the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 among African American legislators, despite anger over racist statements and actions by Japanese politicians and companies, being careful to distinguish Japanese and Japanese Americans. He also allowed NCRR to use his congressional office during a 1987 lobbying trip. He remained in Congress until 1992, then, after a ten year absence, returned in 2002 to serve three more terms.

Community Leaders

This is kind of a catch-all category that brings together three notable and very different lives. Arnold Maeda (July 17, 1926–Sept. 10, 2020) was born in Santa Monica and grew up in West Los Angeles, where his parents ran a nursery. Incarcerated at Manzanar with his family, he was president of the Manzanar High School Class of 1944. After a varied career as a chick sexer, aerospace worker, and insurance salesman, he became one of the leaders of the Venice Japanese American Memorial Monument Committee (VJAMM) that successfully built a memorial at the corner of Venice and Lincoln Boulevards—the site where Japanese Americans from Venice, Santa Monica, and other nearby areas gathered to be taken to Manzanar in April 1942. It remains one of the few memorials built at such gathering or pickup sites. After his passing, VJAMM and the Manzanar Committee established an annual Arnold Maeda Manzanar Pilgrimage Grant for college students interested in helping with the Manzanar Pilgrimage.

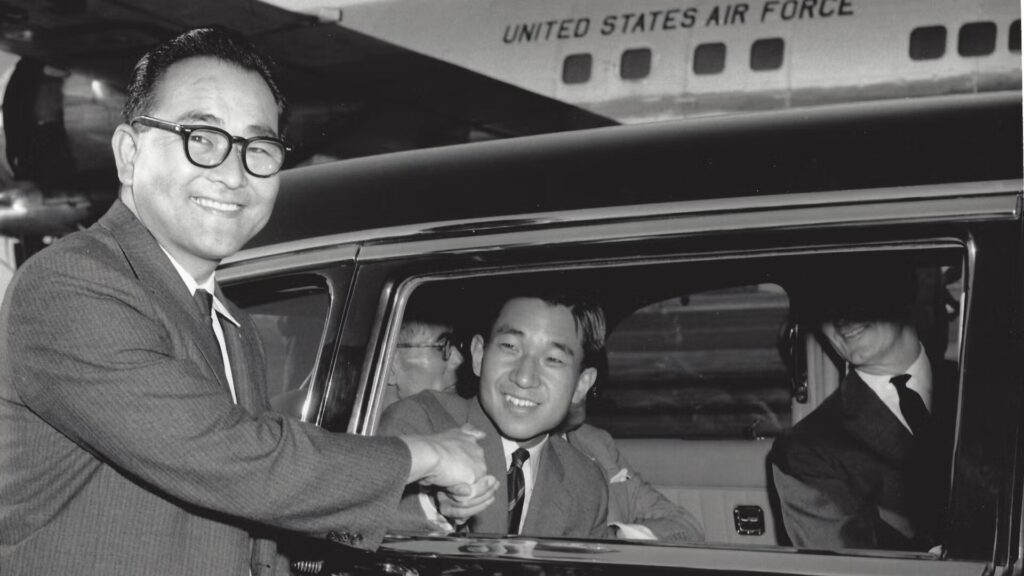

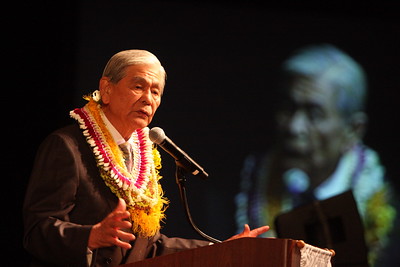

Best known as the governor of Hawai‘i from 1973 to 1986, George Ariyoshi (Mar. 12, 1926) is likely the last person standing of those who remade Hawai‘i politics through the “Democratic Revolution” of 1954. Born and raised in Honolulu, the son of an Issei sumo wrestler, Ariyoshi was the senior class president at McKinley High School in 1944. Subsequently drafted in the army, he served in the Military Intelligence Service in postwar Japan. Taking advantage of the GI Bill, he graduated from Michigan State University in 1949 and University of Michigan Law School in 1952, returning to the islands to start his own practice. As part of a Democratic Party slate that flipped Hawai‘i politics in 1954, the twenty-eight year old Ariyoshi was elected to the Territorial House of Representatives, serving there until 1958. He subsequently served in the Territorial/State Senate until 1970, when he was elected lieutenant governor. When Governor John A. Burns fell ill in 1973, Ariyoshi served as acting governor and was elected to a full term in 1974. Considering he was the first Asian American governor of a U.S. state, the longest serving governor of Hawai‘i, and that he is the rare politician who has never lost an election, Ariyoshi seems less well-known and less celebrated than he should be.

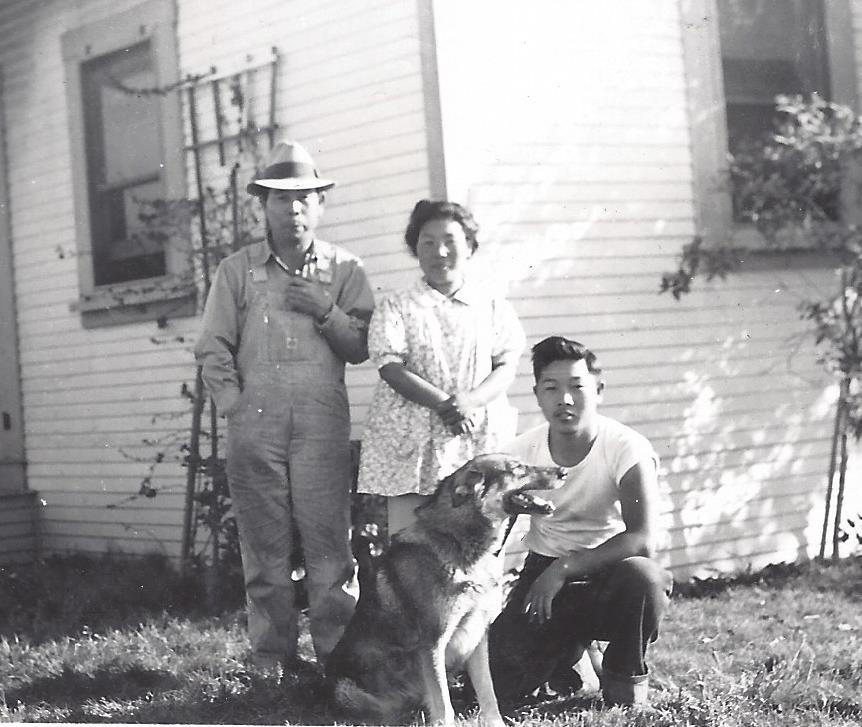

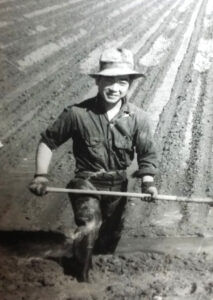

Bob Sakata (April 15, 1926–June 7, 2022) rose from humble beginnings to become one of the biggest farmers in Colorado. Born in San Jose and raised on a rented ten-acre family farm in Alameda County, Sakata and his family were incarcerated at Tanforan and Topaz. Like many Nikkei, Sakata was influenced by Colorado Governor Ralph Carr’s relatively welcoming words and left camp to work on a dairy farm in Brighton, striking up a friendship with its owner, Bill Schluter, who lent Bob and his family the money to purchase forty acres. Despite the early deaths of his older brother and father, and being seriously burned in a shop explosion, Sakata Farms—which included his wife, the former Joanna Tokunaga—grew quickly to meet the demands of chain stores and farmed upwards of 3,000 acres of sweet corn, onions, and other crops at their peak. He was also active in the community, taking leadership positions in many agricultural organizations and raising money for the Platte Valley Medical Center, as well as the National Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism in Washington, D.C.

Artists

And finally, we’ll end with three artists who expanded the boundaries of art in the decades after World War II.

Satoru Abe (June 13, 1926–Feb. 4, 2025) was born and raised in Honolulu and received his first art training there before venturing to California in 1948 and eventually moving to New York City. After marrying Ruth Tanji, a textile and fashion designer from Hawai‘i whom he met in New York, the couple returned to Honolulu, where Abe became part of a group of young artists that met at the Metcalf Chateau. He and his wife returned to New York in 1956, where they spent the next sixteen years, returning to the Islands in 1972. Though he began as a painter, Abe is best known for his metal and wood sculptures, which are often characterized by distinctive tree-like forms that seem to grow organically. Widely exhibited in both Hawai‘i and on the U.S.continent, he continued to produce art well into his 80s and 90s.

Weaver and fiber artist Kay Sekimachi (Sept. 30, 1926) grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area and was incarcerated at Tanforan and Topaz as a teenager. At Topaz, she honed her burgeoning interest in art at the Topaz Art School and at Topaz High School, taking classes in painting, costume design, interior decoration, and origami. Initially resettling with her family in the Midwest, they returned to Berkeley in 1945, where Sekimachi attended the California College of Arts and Crafts. She studied weaving with textile artist Trude Guermonprez, who encouraged her to apply her skills to art pieces beyond the purely utilitarian. She later worked with wood craftsman Bob Stocksdale—whom she later married—on a series of Marriage of Form pieces that included her fiber forms molded around his wood bowls. Widely recognized and exhibited to this day, she has expanded the possibilities of weaving and fiber art as fine art.

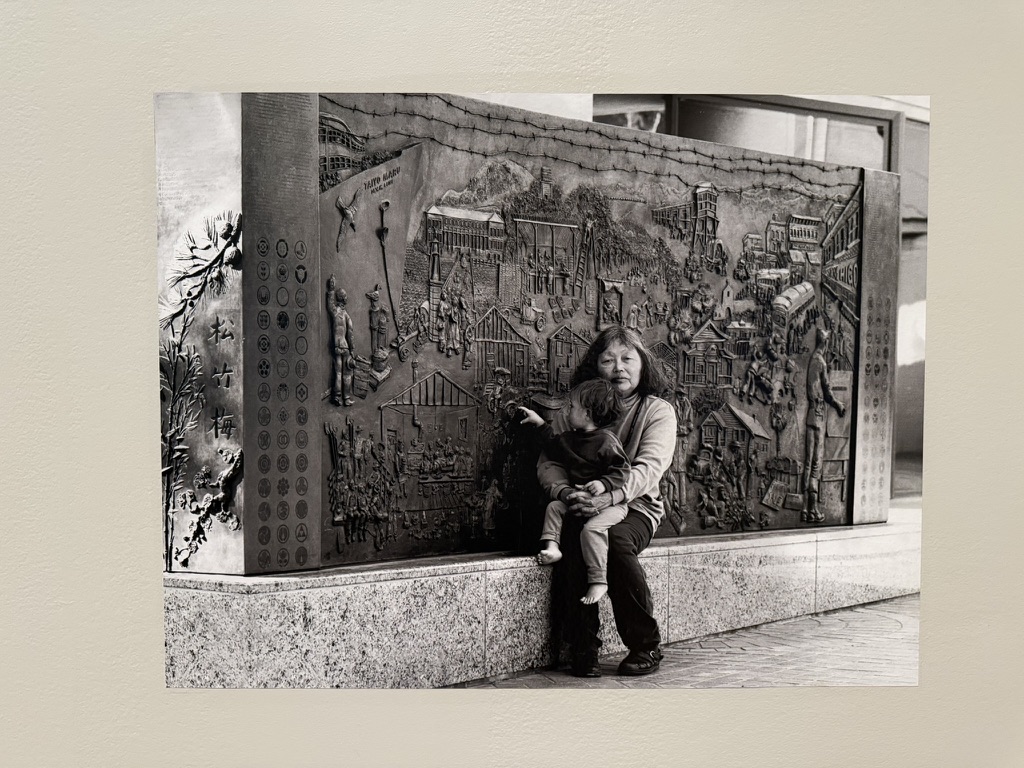

And lastly, there is Ruth Asawa (Jan. 24, 1926 to Aug. 5, 2013). Like Sekimachi, Asawa’s wartime incarceration as a teenager proved to be a formative artistic experience: from observing the weaving of camouflage nets at Santa Anita or learning from older incarceree artists at Rohwer. Although she was born and grew up in Norwalk, California, she became strongly associated with the San Francisco Bay Area after the war. After leaving camp, she studied at Black Mountain College, an experimental art school in North Carolina, and traveled in Mexico, where she first observed the looped wire form she would hone into her signature hanging wire sculptures. She met architect Albert Lanier at Black Mountain, and the two married in San Francisco, where they built their home, all while Asawa continued to create art, exhibit, and raise six children. Asawa is also celebrated for her public art—some of which explicitly draws on her wartime incarceration—and her teaching and activism. Since her passing, her fame has skyrocketed. In recent years, a full biography, several exhibit catalogs, and four children’s or young adult books have been published about her life and work, and her looped wire sculptures have been featured on a series of postage stamps. Most recently, a sprawling retrospective exhibition focused on Asawa was created at New York’s Museum of Modern Art—a large exhibit that will be there on her 100th birthday. One of my New Year’s resolutions is to go see it. It should be one of yours as well!

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director. A special thanks to Patricia Wakida, who reviewed the descriptions of the selected writers and artists.

Catch up on previous editions of Nisei Notables here.