April 19, 2023

Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Lawrence Ferlinghetti are household names among the leftist literati, but you’ve probably never heard the name Shig Murao. You’re not alone. Despite the fact that Shig was a fixture in the San Francisco Beat scene as co-owner of City Lights Bookstore and a central figure in the Howl scandal, his story has been systematically erased from the record. Today, thanks to the work of writers Patricia Wakida and Richard Reynolds, we bring you the story of Shig Murao.

Shigeyoshi Murao and his twin sister, Shizuko, were born on December 8, 1926 to Issei immigrants in Seattle, Washington. His father owned a butcher shop in Seattle’s now-defunct Westlake Public Market and sent all five of his children to Japanese language school. As Patricia Wakida writes for the Densho Encyclopedia, Shig was a sickly child who spent long stretches of time in bed reading. On the eve of his fifteenth birthday, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and within a matter of months his family had sold off their belongings and joined the rest of the Seattle Nikkei community first at Puyallup and later at Minidoka.

In 1944, Shig enlisted in the Military Intelligence Service, but the war had ended by the time he completed his training. He was deployed to Zama Army Base in Tokyo nonetheless and was assigned to work as a translator for the US Army in occupied Japan. He left his station at the first opportunity he had and was back in the US within a year.

Shig’s postwar path was anything but conventional for Japanese American men of his generation. When he returned to the US, he lived briefly with his family in Chicago before making his way to San Francisco in the early 1950s. There, he worked as a bartender at Vesuvio Cafe, a regular haunt for San Francisco Beats and Jack Kerouc’s favorite writing spot. Shig became a fixture of the Beat scene and eventually was hired to work across the street at City Lights Bookstore, a landmark bookstore and publishing house founded in 1953. When founder Peter Martin sold his share of the store to Lawrence Ferlinghetti in 1955, Shig became the store’s full time manager and — having invested $500 of his own savings in the purchase — an official co-owner of the iconic bookstore.

Shig became a fixture at City Lights, known both for his wit and for his many eccentricities. As Richard Reynolds wrote in his Shig Murao website, he was “a self-described ‘Coke sucker,’ [who] drank more than a dozen cans a day. He was so obsessed with Coke that he would sketch out advertising campaigns for the soft drink and send them off to the company.”

On one occasion, a tourist asked Shig if he was Chinese. He said no, but quickly pulled out a wooden eggbeater he had picked up in Chinatown. As he twirled it between his palms, he solemnly told the wide-eyed tourist that it was a Buddhist prayer wheel. And when Immigration officials snooping around City Lights threatened to “send him back to where he came from,” he replied: “Okay, okay. Send me back to Seattle.”

Reynolds, who had a deep friendship with Shig, went on to write that “If he didn’t like you or suspected you had an agenda, he could be coldly dismissive. But once he knew and accepted you, he was warm, charming, and very funny.”

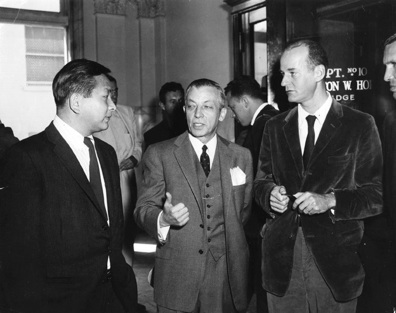

Two years into his tenure at City Lights, Shig found himself swept up in one of the great literary scandals of the 20th century. On May 21, 1957, he was working the counter at City Lights. Included in the many books he sold that day, were copies of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems. The collection was controversial for its brazen use of profanity and candid descriptions of sex and drugs. Earlier that year, US Customs officials had seized imported copies of the book in order to prevent its sale, but Ferlinghetti printed it domestically and kept it in stock at City Lights. Unbeknownst to Shig, two of the customers who purchased the book on May 21 were undercover cops; they returned a few days later with a warrant and arrested him for selling the “obscene and indecent” book.

Shig was astonished by the arrest, exclaiming “imagine being arrested for selling poetry!” In his brief account of the trial, “Footnotes to My Arrest for Selling Howl,” he wrote:

“I was taken by patrol car to the Hall of Justice, three blocks from the store. In the basement, I was fingerprinted, posed for mug shots and locked in the drunk tank. The cell smelled of piss. There was a piss-stained mattress on the floor. For lunch, they served me wieners, very red.”

The ACLU posted Shig’s $500 bail and provided lawyers to represent him and Ferlinghetti in court. Shig was dismissed early on in the trial because prosecutors couldn’t prove that he’d actually read the book, or “knowingly” sold a text with obscene content. The judge eventually ruled in Ferlinghetti’s favor, arguing that the publication was protected by the First Amendment.

After the trial, Shig resumed his station at City Lights where, according to Reynolds, “Shig referred to himself as ‘Chief Poet Watcher’ and provided a variety of services for poets and others who hung out at the store. There was a bulletin board at the top of the basement staircase where people could leave notes for each other. Visiting poets, musicians, and comedians, along with regulars who didn’t have a stable mailing address, used City Lights as a post office and Shig as their postmaster.”

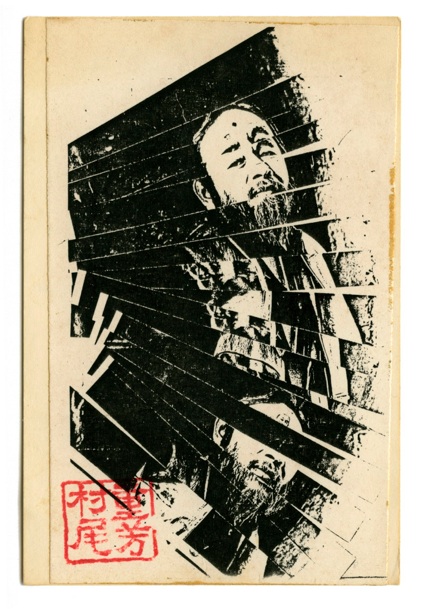

After a stroke in 1975 and a reduction in duties at City Lights, Shig and Ferlinghetti had a falling out that ended Shig’s relationship with his longtime-friend and the bookstore. He channeled his time and creative energy into calligraphy and flute playing. After a second stroke in 1983, he had to abandon his musical pursuits and instead dedicated himself to reviving Shig’s Review, a handmade publication that he had started in 1960 and that prefigured today’s zine movement. Shig filled each of the 80+ issues of the publication with an eclectic combination of poetry, collage, letters, woodcuts and other works of art created by himself, friends, and creative collaborators. He would photocopy each edition himself, then hand them out for free.

A third stroke in 1984 and the onset of diabetes left Shig partially immobilized and in increasingly poor health. After he fractured several ribs on a Muni Bus in 1995, he used much of what remained of his redress payment on a top-of-the-line wheelchair, which he outfitted with Japanese and US flags and “drove around like a sportscar.” Though he remained stubbornly active and independent, his health continued to decline until his death in October 1999.

A little over a decade later, the Howl controversy was immortalized in the art house film by the same name — but Shig was nowhere to be found. In her 2011 article, “In Search of Shigeyoshi Murao,” Patricia Wakida wrote about this erasure:

“Without a doubt, it is a slap in the face to witness the deliberate act of writing people of color out of the mainstream history and culture… I can’t help but wonder, at what point in the screenplay that it was agreed that Murao was a disposable character? How was the inclusion of Shig as a co-defendant (as was historically accurate) hindering the script? What gains were made by streamlining a piece of the story that might have brought a much needed twist of irony and complexity to the film?”

Wakida goes on to praise Richard Reynolds for launching his website/virtual biography of Shig Murao which had been published earlier that year. In 2013, the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley acquired the site so that it could be maintained for future generations of researchers — but as of 2023, his story has been erased from that platform too. Links from the Densho Encyclopedia and every other online resource are now met with error messages. In response to an April 2023 inquiry from Densho, the Bancroft’s Interim Deputy Director and Head of Technical Services, Mary Elings, explained that it had been retired along with a number of other “older and outdated websites that could no longer be supported” but that any link to the site should automatically redirect visitors to the site’s new home in the Internet Archive. Though the Bancroft has been informed of the linking error, it has yet to be corrected. Even those who do find their way to the site’s new home at the Internet Archive will find missing image and text files; most notably the the archived issues of Shig’s Review are no longer accessible.

Shig Murao’s life and afterlife have been shaped by injustice: he was twice imprisoned in direct violation of his constitutional rights, and now he has been sidelined from a story he was central to. But he never let that stop him from defying the social conventions prescribed to him, nor from being unabashedly himself. So let’s raise a virtual Coke to bookslinger and Poet Watcher extraordinaire Shig Murao, and commit to doing our part to keeping his story alive.

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications and Public Engagement Director

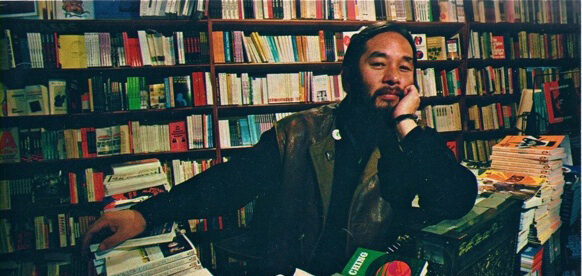

[Header Image: Shig at City Lights, courtesy of ShigMurao.org. Richard Reynolds writes, “This Arnold Newman photo appeared in the March 1970 issue of Holiday magazine. It accompanied a Herb Gold article called “Culture, Counter Culture, or ‘Barbaric Intrusion,’ There’s Something Going on in San Francisco.”]

Sources

Shigeyoshi “Shig” Murao, Densho Encyclopedia, Patricia Wakida

In Search of Shigeyoshi Murao, Discover Nikkei, Patricia Wakida

Shig Murao: The Enigmatic Soul of City Lights and the San Francisco Beat Scene, self-published website/biography, Richard Reynolds

Shig Murao: The Enigmatic Soul of City Lights and the San Francisco Beat Scene, ZYZZYVA, Richard Reynolds