November 4, 2024

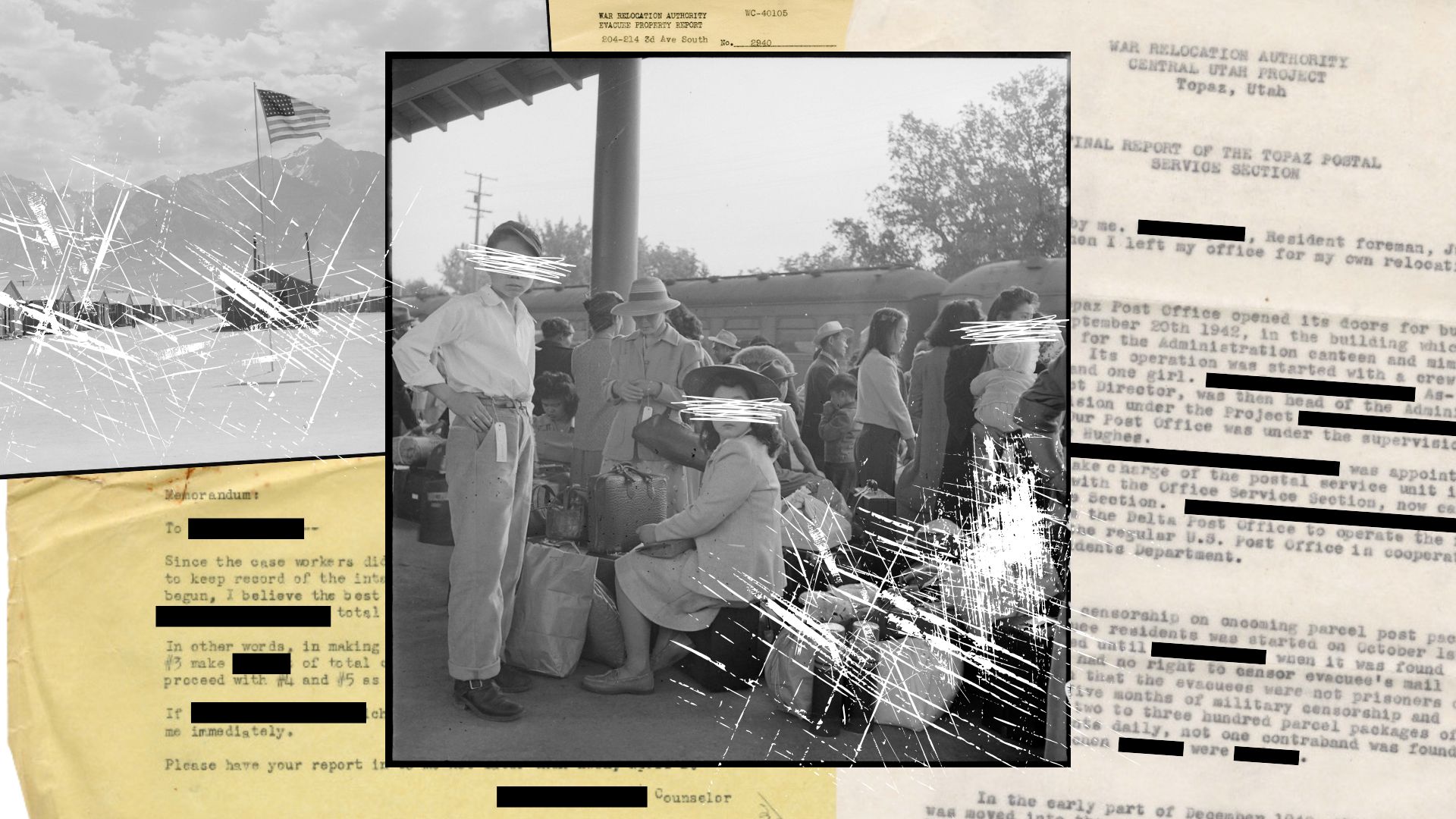

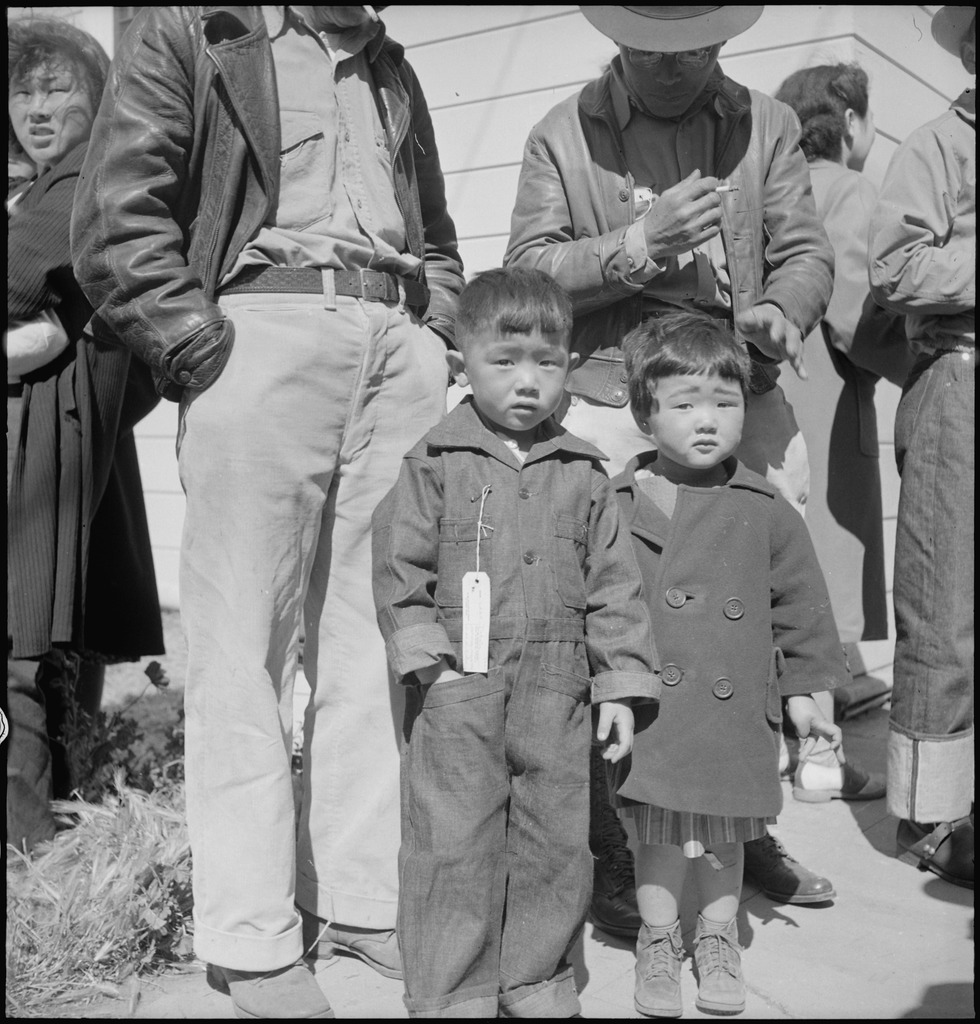

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is probably not a household name for most Americans. This federal agency oversees billions of documents, from the Declaration of Independence to electronic records covering more recent events, as well as a vast collection of historical photos. Among them are important records of Japanese American WWII incarceration: Dorothea Lange’s iconic images of families reporting for forced removal, War Relocation Authority data on the people they imprisoned and where they went upon leaving the camps, and much more.

Managing the National Archives, and its museum and adjacent education center on the National Mall, is a huge responsibility. But instead of educating the public about WWII incarceration and other dark chapters of American history, U.S. Archivist Colleen Shogan has spent the last year quietly whitewashing that history.

Shogan, who was confirmed in May 2023, instructed employees to erase references to Japanese American incarceration from educational materials, and ordered the removal of Lange’s photos of WRA concentration camps from a planned exhibit at the National Archives Museum — claiming it was too negative and controversial. Also targeted for removal were photos of Martin Luther King Jr. and labor activist Dolores Huerta, and references to the displacement and dispossession of Indigenous peoples. According to employees, after a review of an exhibit on Westward expansion, Shogan asked, “Why is it so much about Indians?”

NARA defended this exclusion by claiming “it is imperative that the National Archives welcomes — and feels welcoming to — all Americans.” But let’s be clear: erasing the experiences of people of color in this country is not welcoming. Excluding our stories from the National Archives excludes us from American history.

This is a blatant dog whistle. When Shogan and her senior staff say “average visitors” like “Iowa farmers” should feel welcomed and not “confronted” by the National Archives, they are prioritizing the comfort of white visitors over the inclusion of communities of color. When they say their exhibits must show American history in a positive light, they are keeping the wrongs done by and to our ancestors in the dark.

Whitewashing the “ugly” parts of our history because they might make viewers uncomfortable or anger certain politicians is an act of censorship. It also stands in stark contrast to NARA’s stated mission “to provide equitable public access” to government records “by allowing all Americans of all backgrounds to claim their rights of citizenship, hold their government accountable, and understand their history so they can participate more effectively in their government.” If the stories of only some Americans are represented and uplifted in the National Archives, then only some are able to claim those rights — and none of us can fully understand and reckon with our history.

“It’s the National Archives’ responsibility to protect access to these records because they really belong to all of us,” said Densho Archives Director Caitlin Oiye Coon. “It’s only by confronting all parts of American history, the good and the bad, that we can learn from it and begin to heal.”

In NARA’s own words, “Leading a nonpartisan agency during an era of political polarization is not for the faint of heart.” Let’s hope that Shogan and her fellow leaders at the National Archives develop the courage to choose historical accuracy over censorship — or move out of the way for archivists who aren’t afraid to tell the truth.