February 5, 2024

Through stories of remarkable people in Japanese American history, The Unknown Great illuminates the diversity of the Nikkei experience from the turn of the twentieth century to the present day. Acclaimed historian and journalist Greg Robinson delves into a range of themes from race and interracial relationships to sexuality, faith, and national identity. In accessible, short essays drawn primarily from his newspaper columns, Robinson – along with contributing author Jonathan van Harmelen – examines the longstanding interactions between African Americans and Japanese Americans, the history of LGBTQ+ Japanese Americans, religion in Japanese American life, mixed-race performers and political figures, and more.

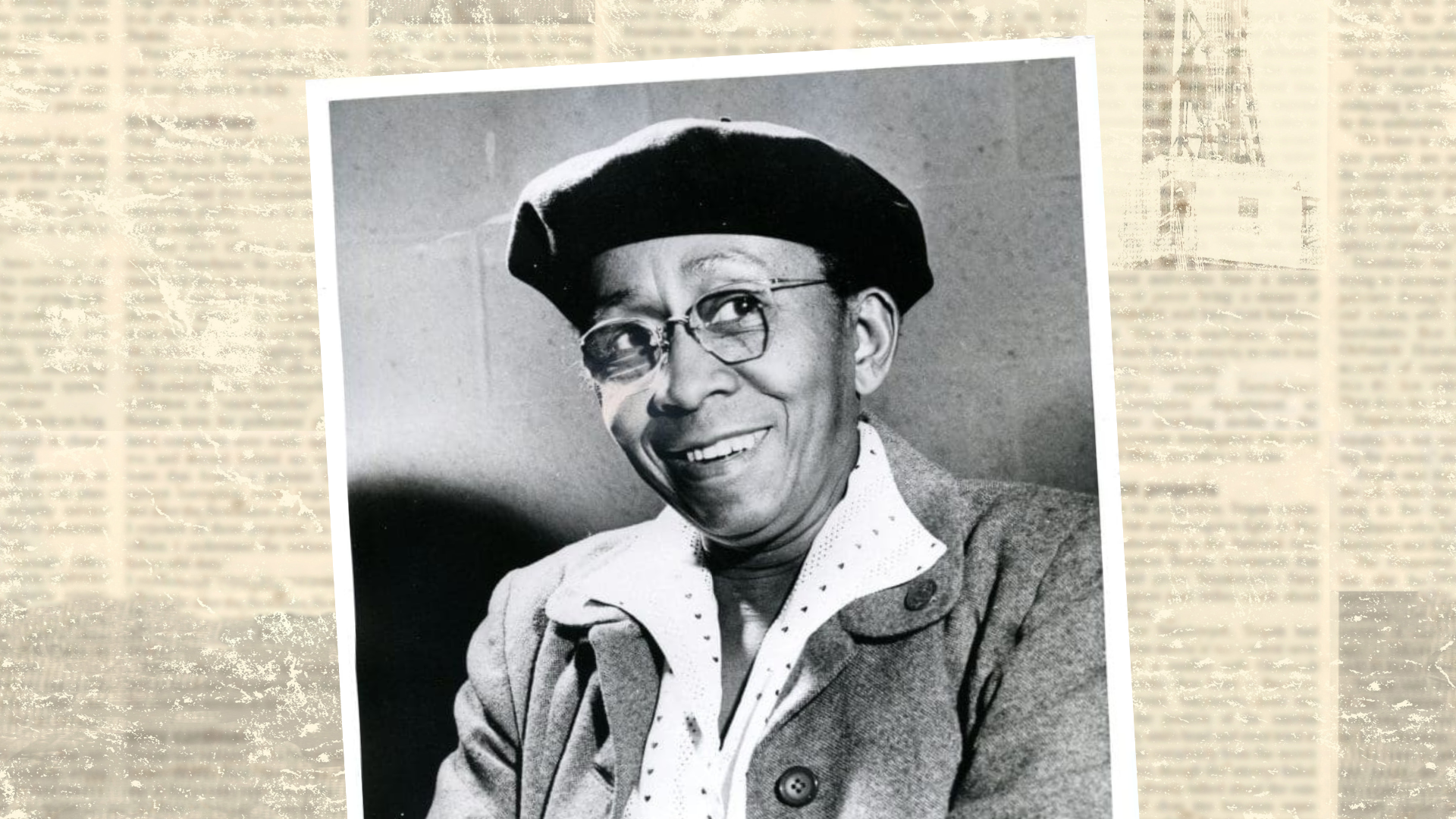

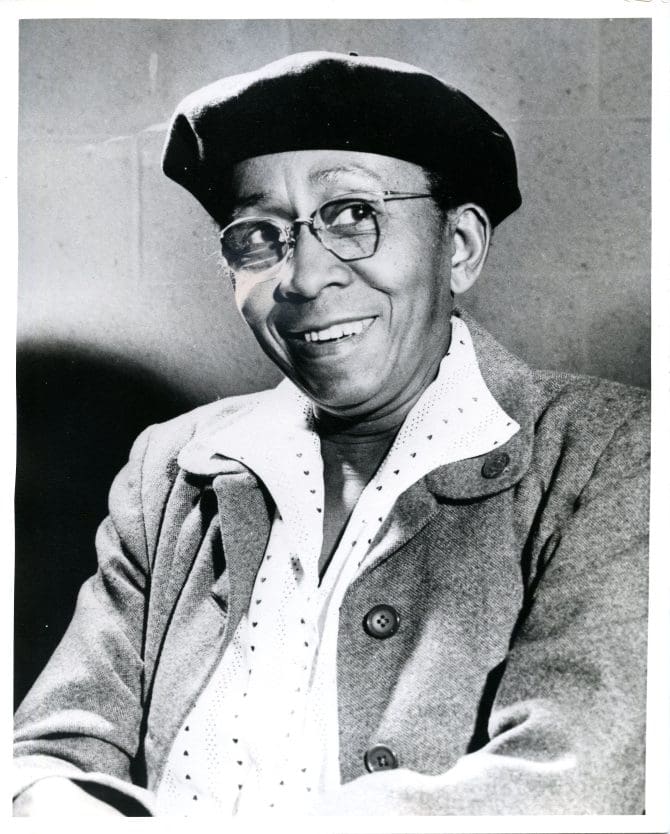

The following excerpt from the book, which was published last month by The University of Washington Press, highlights the little known history of African American solidarity with Japanese Americans through the story of Erna P. Harris. Harris was a dissident columnist for the Los Angeles Tribune who penned scathing critiques of the Japanese American incarceration and, as Robinson illustrates here, her story is well worth remembering.

One part of the history of Japanese American wartime confinement that has been curiously neglected is the disproportionate support offered by Black Americans. Victims of racial injustice themselves, African Americans demonstrated different forms of solidarity to their Nikkei counterparts in the wake of Executive Order 9066. (Issued by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, this order authorized the army to exclude or confine all persons on the West Coast deemed a threat to national security and led to the forced removal of some 110,000 US citizens and long-term resident aliens of Japanese ancestry from the region and their mass confinement in a network of camps inland.) In particular, numerous African American writers and journalists spoke out in support of the rights of Japanese Americans. The celebrated poet Langston Hughes devoted several columns in the Chicago Defender to opposing the government’s policy as racist and tyrannical. The critic and novelist George Schuyler not only supported the rights of Japanese Americans in his articles for the Pittsburgh Courier but offered funds from his own pocket to help found a New York chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), the organization’s first interracial branch.

One outstanding dissident was columnist Erna P. Harris of the Los Angeles Tribune. Erna Prather Harris was born on June 29, 1908, in Kingfisher, Oklahoma, a small town about forty miles northwest of Oklahoma City. After attending segregated schools in Oklahoma, she enrolled at Wichita State University, where she served as a reporter and editor of the school’s newspaper, the Sunflower (according to one source, she won a journalism award, but when the town newspaper came to take a picture of the prize-winning student and discovered that she was Black, they decided to cancel the shoot). Upon graduating with a bachelor of arts degree in journalism in 1936, she had difficulty finding a position as a reporter, so she decided to start her own weekly newspaper, the Kansas Journal. It operated for three and a half years. However, when Harris ran an editorial in October 1939 opposing conscription, she angered readers and advertisers and was forced to close her newspaper.

In 1941 Harris moved to Los Angeles and was hired as a reporter for the Los Angeles Tribune, the newest (and least established) of the city’s three African American newspapers. Since the Tribune had a female editor, Almena Davis, it might have been easier for Harris as a woman to gain employment. Once at the Tribune, Harris wrote features and began an editorial column, “Reflections in a Crackt Mirror.” Outside of her newspaper work, she also was active with the local chapter of the nonviolent human relations group Fellowship of Reconciliation (for).

In spring 1942 the Los Angeles Tribune distinguished itself as the sole Los Angeles newspaper to formally oppose mass removal. Harris was particularly outraged by Executive Order 9066. As she later recalled in her column, “Ever since the evacuation of Americans of Japanese ancestry and Japanese along the Pacific Coast was proposed, I have pointed out that the issue was one of race and on that basis affected anyone who was physically distinguishable as ‘colored’” (February 7, 1944). Worse, it was a government action that thereby gave official approval to prejudice. As Harris wrote in spring 1942, “To visit evacuation [evacuated] neighborhoods and talk with neighbors of the ‘evil, treacherous, fifth column menaces’ who are being summarily moved away, who have been adjudged guilty without any trial at which to claim innocence was to acknowledge an event with all earmarks of a legalized community lynching.” Harris’s position was scored by popular syndicated columnist Westbrook Pegler, who dismissed “E.P.H.” as naive. Pegler’s attack had the effect of publicizing Harris’s views nationwide.

Once mass removal took place, Harris seems not to have spoken about government actions toward Japanese Americans, though she mentioned Nisei among the ranks of racial minorities deserving justice. In late November 1943 reports of rioting among “disloyal Japanese” at the government’s “segregation center” at Tule Lake brought anti-Japanese American sentiment in Southern California to a climax. Politicians and organizations called for a military takeover of the camps and for the end of resettlement. In a column Harris decried the hysteria over “disloyalty,” laying into the bigots and expressing sympathy for Japanese Americans who had been “set on” as part of the inflammatory campaigns of the Hearst press:

“Eighteen months ago the evacuation of the Issei and Nisei was being called a matter of military necessity on threat of imminent invasion. In a few months it was called protective custody for their own safety—such cannibals are we, their erstwhile neighbors, alleged to be. But now, as the interests which have long wanted them eliminated from California in the hysteria of war-bred hatred dare to come out into the open, there comes the call for their permanent exclusion from California, for treating them as war prisoners, for depriving them of citizenship, and from a man pledged to enforce the law, [Los Angeles County] Sheriff [Eugene] Biscailuz, comes a plea for sending many of them to Japan in exchange for prisoners of war. Such a move would involve some American citizens. If citizenship is to become a matter of racial or national predeterminism or of periodic authoritarian changes, who will be safe from the whims of the powerful?” (Reflections, Los Angeles Tribune, November 22, 1943)

In the months that followed, Harris devoted several more columns to defending Japanese Americans. In her January 3, 1944, column, for example, she denounced an anti-Nisei Christmas cartoon by Los Angeles Times cartoonist Ed Leffingwell. Harris snapped, “Friends, this is how Hitler made little Nazis: by reaching the children and youth through stories and pictures, he taught them to fear and hate certain groups.” Harris explained her own insight into the question:

“Through friends and newspapers I have maintained a fairly close contact with the evacuee-victims of our lack of confidence in American education and government agencies. On Christmas Eve it was my pleasure to have as a houseguest an old friend who is teaching in the relocation center at Poston. I hasten to suggest that Mr. Leffingwell could find among the Japanese and Nisei internees some real characters whose story, recounted by him in picture, would set before his small readers an example of courage, sensitivity, forgiveness and humility such as would set his cartoon aside from the petty humdrum of its fellows.”

Harris’s concern over the treatment of Japanese Americans reflected her larger interest in struggles against discrimination by minorities, including Jews, Mexican Americans, and Asians. In an article in late 1944 in a new multiracial magazine, Pacific Pathfinder, she deplored the racial bias of white nativists such as the Native Sons of the Golden West and scored John Sinclair, a state official with the American Legion, for making a speech in Santa Barbara calling for pressure to discourage Japanese Americans from returning to the Pacific Coast and for openly affirming, “I would like to keep this a country for Caucasians.”

Harris warned of the dangerous implications of such attitudes for all minorities: “Americans of Chinese ancestry share in disproportionate measure the apprehension of other non-Whites with regard to the summary treatment of Americans of Japanese ancestry. Tightening of residential restrictions against them, for instance, in the neighborhood surrounding San Francisco’s ‘Chinatown’ gives basis for their fears.” In February 1946 she complained in her Los Angeles Tribune column that all the events for Brotherhood Week that year were being hosted by whites seeking to reach out to Blacks. Harris insisted that African Americans should hold their own events and reach out to others: “Joint hosts on the negroes’ invitation would be Nisei, American Indians and other Americans whose physical characteristics make them detectable. I have heard of no such observance during Brotherhood week.”

During the postwar years, Harris welcomed a group of outstanding Nisei who joined her on the staff of the Tribune. They included Hisaye Yamamoto, who started as a columnist and editorial writer in June 1945 (at the modest salary of thirty-five dollars per week), and later sports editor Chester “Cheddar” Yamauchi and his wife, the future playwright Wakako Yamauchi.

In 1952 Harris left Los Angeles and moved to Berkeley, California, where she operated a print shop and continued to be active in a number of peace and civil rights organizations. She was appointed to the National Board of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) in 1956 and regularly traveled to WILPF congresses in Europe and Asia, including one in Birmingham, England, in 1956. She was a member of the WILPF delegation that visited the USSR in 1964 to participate in the US-Soviet Women’s Seminar in Moscow. Harris also grew active in cooperatives in the Berkeley area and in February 1983 was elected to the board of directors of the Berkeley Co-Op, the nation’s largest cooperative. Erna P. Harris died on March 9, 1995. She was subsequently honored by the naming of a public housing project, Erna P. Harris Court, in the city of Berkeley.”

–

Greg Robinson is professor of history at l’Université du Québec à Montréal and author of several books, including The Unsung Great: Stories of Extraordinary Japanese Americans and After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life.

Excerpt from The Unknown Great: Stories of Japanese Americans at the Margins of History published with permission from the University of Washington Press. Learn more about the book here.