April 25, 2023

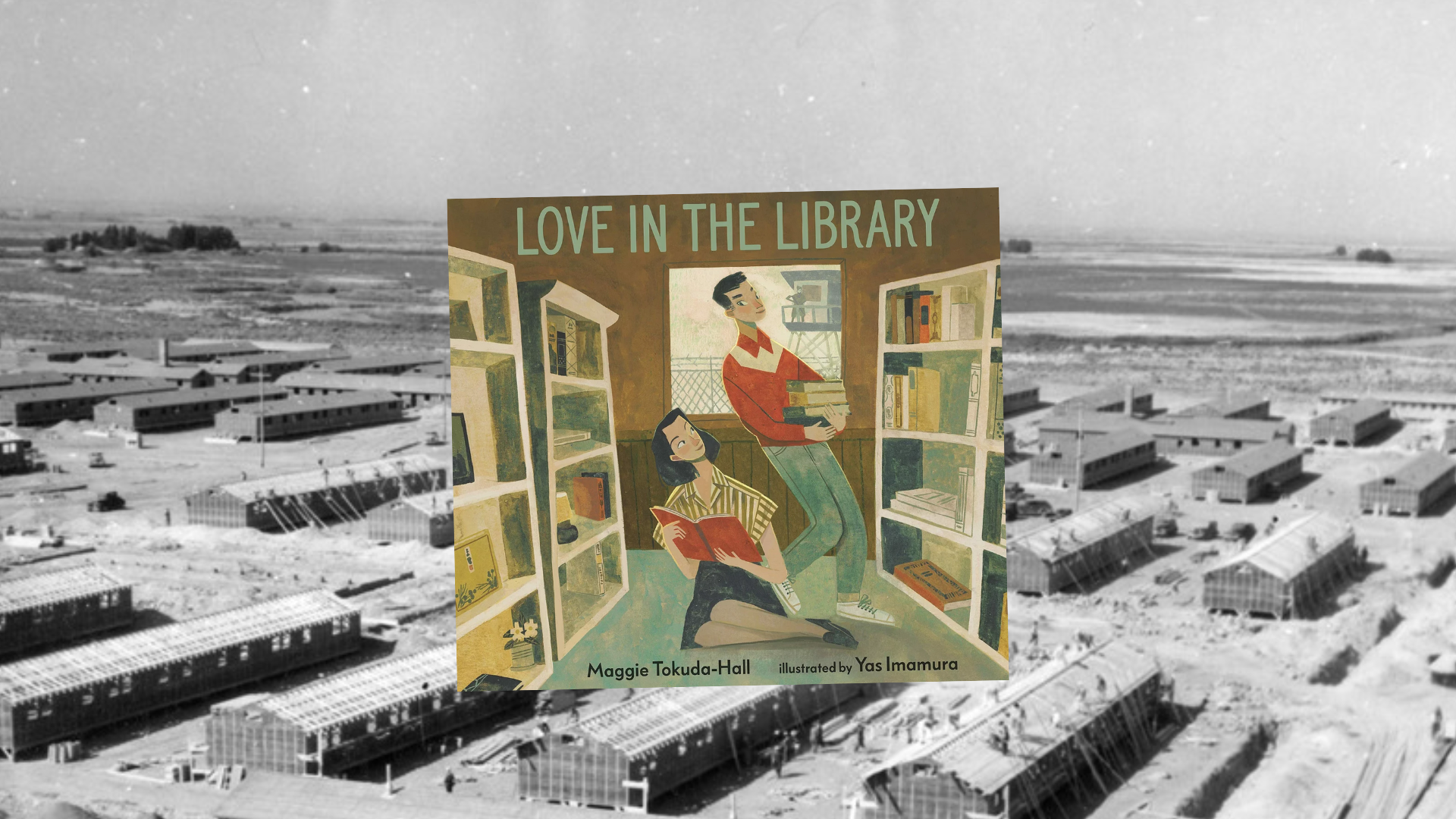

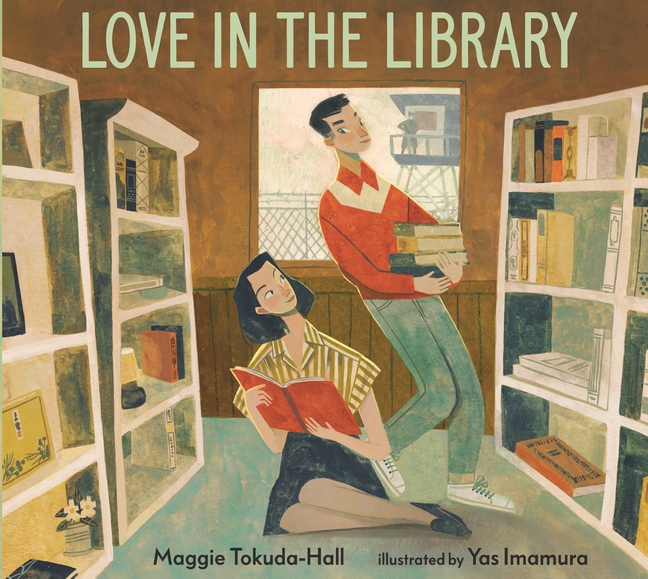

Earlier this month, author Maggie Tokuda-Hall received a troubling offer from publishing giant Scholastic: they would license Love in the Library, her acclaimed children’s book based on her grandparents’ experiences in Minidoka, but only if she agreed to remove all mentions of racism from her author’s note.

Tokuda-Hall said “absolutely not” and shared the “deeply offensive offer” publicly, calling out Scholastic’s decision to prioritize the comfort of white readers over the hard truths of our history in the midst of rising book bans, attacks on Critical Race Theory, and other attempts to silence marginalized voices. After a well-deserved backlash, Scholastic issued an apology — though any concrete steps to remedy the harm of their actions have yet to be announced.

In an exchange with Densho Media and Outreach Manager Nina Wallace, Tokuda-Hall shared her thoughts on Scholastic’s attempted censorship, how it fits into the “deeply American tradition of racism,” and our collective responsibility to fight back for a better future.

Nina Wallace: Can you share a little about how you learned your grandparents’ story? Did they talk about their time in Minidoka with you when you were growing up? What made you want to share their story with a wider audience?

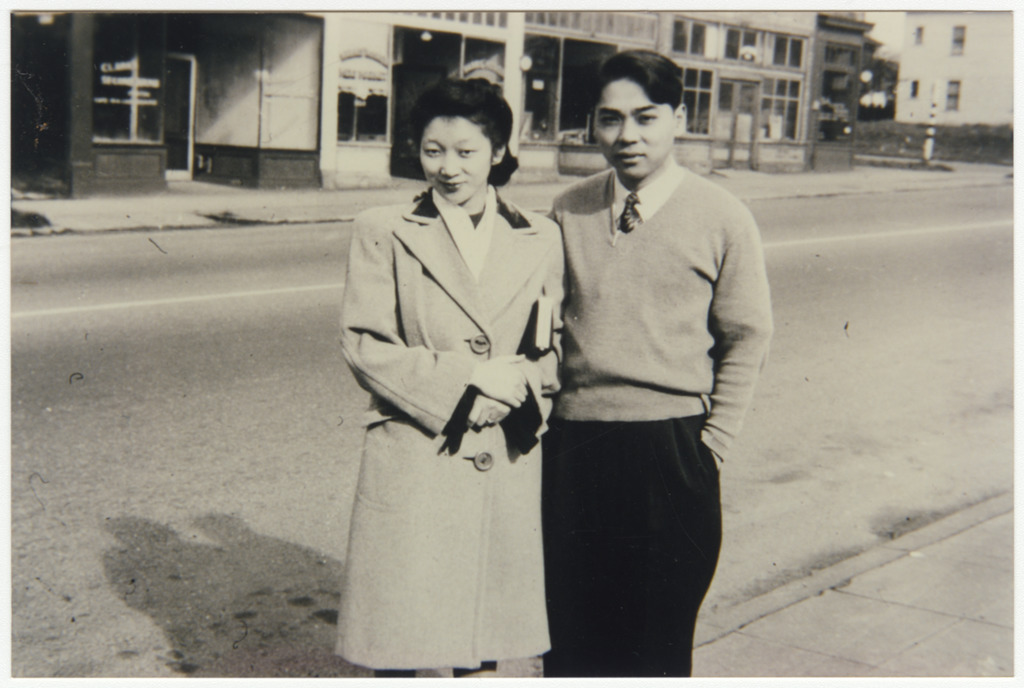

Maggie Tokuda-Hall: I don’t remember the first time I was told their story. It’s just a story I’ve always known, as much a part of my world as recess. [My grandfather] George died when I was only a year old. But [my grandmother] Tama, I was blessed to know well into my adult life. She didn’t talk about incarceration often. Hardly ever, really, with me. But she wrote about it, in speeches for other survivors. She was a very talented writer, and my mother was a talented journalist. And so my memories of discussing this as a child center largely around my mother, who is not only a gifted communicator, but a person with an unwavering dedication to telling the truth, in all its complexity and nuance.

It had never occurred to me to write their story as a children’s book until 2016, when President Trump took office. His very first executive order was the Travel or Muslim Ban. And it was clear to me, as it was clear to us all, that he was going to use his time in power to enact a white supremacist agenda. And I asked myself what could I do, what did I have to offer in this terrible time to children? And I realized I had this wonderful story from my own family. About the cruelty of those kinds of policies, but also about the incredible resilience of those who suffer under them.

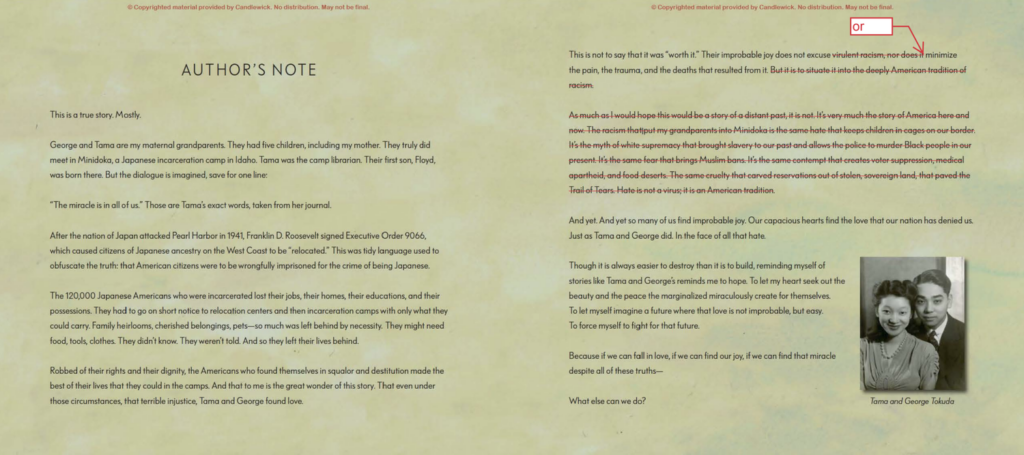

NW: There’s a line in your book that really stuck with me: “To fall in love is already a gift. But to fall in love in a place like Minidoka, a place built to make people feel like they weren’t human—that was miraculous.” I think it’s interesting because often we associate “miracles” with these sort of heartwarming, feel-good stories, but Tama and George’s love story is more complicated and bittersweet because of where it happened. You also get at this in your author’s note — in a line that Scholastic deemed too threatening for “sensitive” readers — how their “improbable joy” exists alongside “virulent racism.” I wonder if you could say a little more about that irony, and why it’s harmful to present this as “just a simple love story” without also telling the story of how Tama and George found themselves in Minidoka in the first place?

MTH: I have spent many hours rolling this story over in my mind, contemplating the responsibility of sharing it. And to me, the greatest insult I could do to them, the greatest failure to live up to the responsibility of their story would be to soften it until it resembled the comfortable pablum of jingoism. George had two pharmacies when he was incarcerated. He lost them both. It is no surprise to any reader of Densho, but Japanese Americans lost everything because they posed an imaginary threat to a nation in search of a scapegoat.

NW: Another major piece that Scholastic wanted to cut from your author’s note was a paragraph connecting Japanese American WWII incarceration to other examples of racial injustice, including many that are ongoing as we speak. Why do you think it’s so important to make those connections and to situate WWII incarceration within this larger “American tradition,” as you call it, of racism and violence?

MTH: State sanctioned, racist violence defines our history. To say otherwise is to misunderstand power on a fundamental level. It is also a grave disservice to the children who would read this story, to let this story be presented as aberrant, as comfortably in the past. There are children right now bearing the consequence of the imaginary threat they pose to our nation; just last week, Ralph Yarl was shot in the head because of it. I wrote this story so that those children would see that they’re not alone. That, in fact, all marginalized people of the United States exist as part of this incredible history of strength, joy, and resilience. And we do all that in spite of the hate that would deny us our lives and our happiness. Because we’re just that powerful.

NW: This comes at a time when there’s already a huge backlash against educating young people about racism, xenophobia, queerness, and really any marginalized identities or histories. What do you hope people can learn from your experience?

MTH: I hope that publishers will face enough public pressure to start taking a stand against this rise in book bans. If not for the marginalized creators whose stories they peddle, then for themselves. These bans will not stop in schools. Or in libraries. Already legislation is on the floor at the state level in Tennessee to make it a felony for publishers to send certain materials to incarcerated people. And George Santos and Marjorie Taylor Greene are bringing legislation to the floor that would make publishers liable. This culture is coming for them. Corporations won’t save us. But I sure wish they’d try to save themselves. Right now they’re outsourcing this fight to authors and educators. But in Scholastic’s case, they’re a BILLION DOLLAR corporation. They have power. I’d like to see them use it.

NW: This whole ordeal must have been extremely difficult for you — what do you do to take care of yourself in moments like this? What’s something that’s giving you hope as you move forward?

MTH: Self care is important. There are also moments when it can wait. I stepped forward publicly because I knew I had the infrastructure of support that so many do not. I’m both financially and emotionally supported in a way that makes me uniquely privileged, and by extension uniquely responsible to take a stand. I hope that others can honestly evaluate what privilege they have and figure out how best they can leverage it to fight for a better future. I hear a lot about how Gen Z has it right, and the kids will fix the mess our country is in. And I disagree. The children can’t save us. It is our job to fight for them.

—

Read Maggie Tokuda-Hall’s full response to Scholastic on her blog.

Learn more about Love in the Library (Candlewick Press, 2022) here.