June 1, 2022

Here at Densho we talk a lot about the importance of preserving the history of WWII Japanese American incarceration. But we are well aware that this one moment in history doesn’t exist in a bubble. Acts of racism and violence have been part of American history since its founding and, tragically, they don’t just exist in the past.

This month’s racist killing spree in Buffalo and the uptick in anti-Asian violence over the past few years are just two recent reminders that racism and xenophobia are still potent forces in our country. We can’t hope to heal from our past — or extinguish racist violence from our present — if we don’t address the problem at its core.

We need to be able to talk about the systemic nature of racism and xenophobia, in the hope that future generations will have the tools they need to overcome it. That’s why the ongoing attacks on Critical Race Theory (CRT) are especially concerning to us.

What Does Critical Race Theory Have To Do With Japanese American History?

You might be wondering what CRT has to do with WWII Japanese American incarceration. Let me explain.

First, let’s make sure we’re on the same page about what Critical Race Theory is. To put it very simply, CRT is the well documented understanding that systemic racism exists at the very foundation of our country and continues to shape our lives today, to the detriment of Black, Indigenous, Asian, Latinx, and other people of color — and to the benefit of white people.

The mass round-up of people of Japanese descent during WWII, and the decades of laws and social persecution that preceded and followed incarceration? That’s all part of the bigger system of American racism and xenophobia. We can’t fully understand these dark moments in American history unless we see them as part of a pattern that has played out over and over and over again. (We go into more detail about this in our “Other”: A Brief History of American Xenophobia short film and curriculum.)

The CRT Backlash Is Rooted In Fear And Anti-Blackness

CRT was developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw, a Black civil rights advocate and scholar who also developed the theory of intersectionality. But the movement to block CRT is much broader than just trying to ban a theory — it targets the very underpinnings of anti-racist education.

The people behind the anti-CRT movement want us to believe that talking about systemic racism is the problem, not the systemic racism itself. But we know that’s not true.

As historians and archivists who document a part of American history that was profoundly shaped by racism, we are painfully familiar with what happens when this sort of bigotry goes unchallenged. If we have any hope of learning from our past, we need to talk more about our country’s racist history. Not less.

It’s also important to note that the movement against CRT is rooted in anti-Blackness. It was started in direct opposition to the public outcry over the murder of George Floyd in May 2020. According to research conducted by Race Forward, “the term ‘systemic racism’ was used more times in the media after the murder of George Floyd than in the last 30 years combined.” That made some people a little uncomfortable.

Christopher Rufo, a senior fellow at the conservative think tank Manhattan Institute, turned that discomfort into a lucrative platform by inventing and inflaming conflict over CRT and the anti-racist practices it inspired. Rufo called CRT an “aggressive new racialist ideology to fund a corrupt consultant class while maligning all white people” and spearheaded a strategic campaign to eliminate anti-racist education and training from schools and government agencies across the country.

What’s At Stake

Since January 2021, “42 states have introduced bills or taken other steps that would restrict teaching critical race theory or limit how teachers can discuss racism and sexism. Seventeen states have imposed these bans and restrictions either through legislation or other avenues,” according to Education Week. In several states, racial equity trainings and initiatives have been halted or threatened as a result of this backlash.

In addition to anti-racist education being an essential component of WWII incarceration history, we need it to combat white nationalist conspiracy theories like the “Replacement Theory” that inspired the Buffalo massacre.

Plus, we all stand to gain from learning about structural inequity and finding ways to evolve past it. As Race Forward puts it: “There is benefit for everyone in addressing systemic racism. By having honest and courageous conversations about systemic racism, people of all backgrounds have come to a deeper understanding of themselves, their communities, and have achieved collective gains towards a more just and inclusive society.”

So What Can You Do to Help?

- Find out if there are any local or statewide initiatives to block CRT and join groups who are opposing them. Start with Education Week’s map of where Critical Race Theory is under attack.

- Contact your representatives and local school boards to let them know how important it is to continue having conversations about racial justice.

- Keep teaching our history in a way that engages anti-racist ideology! Our own curriculum for “Other”: An Brief History of American Xenophobia and on combatting the Model Minority Myth are great places to start. Organizations like Race Forward, Facing History and Ourselves and Learning for Justice are also creating great resources.

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications & Public Engagement Director

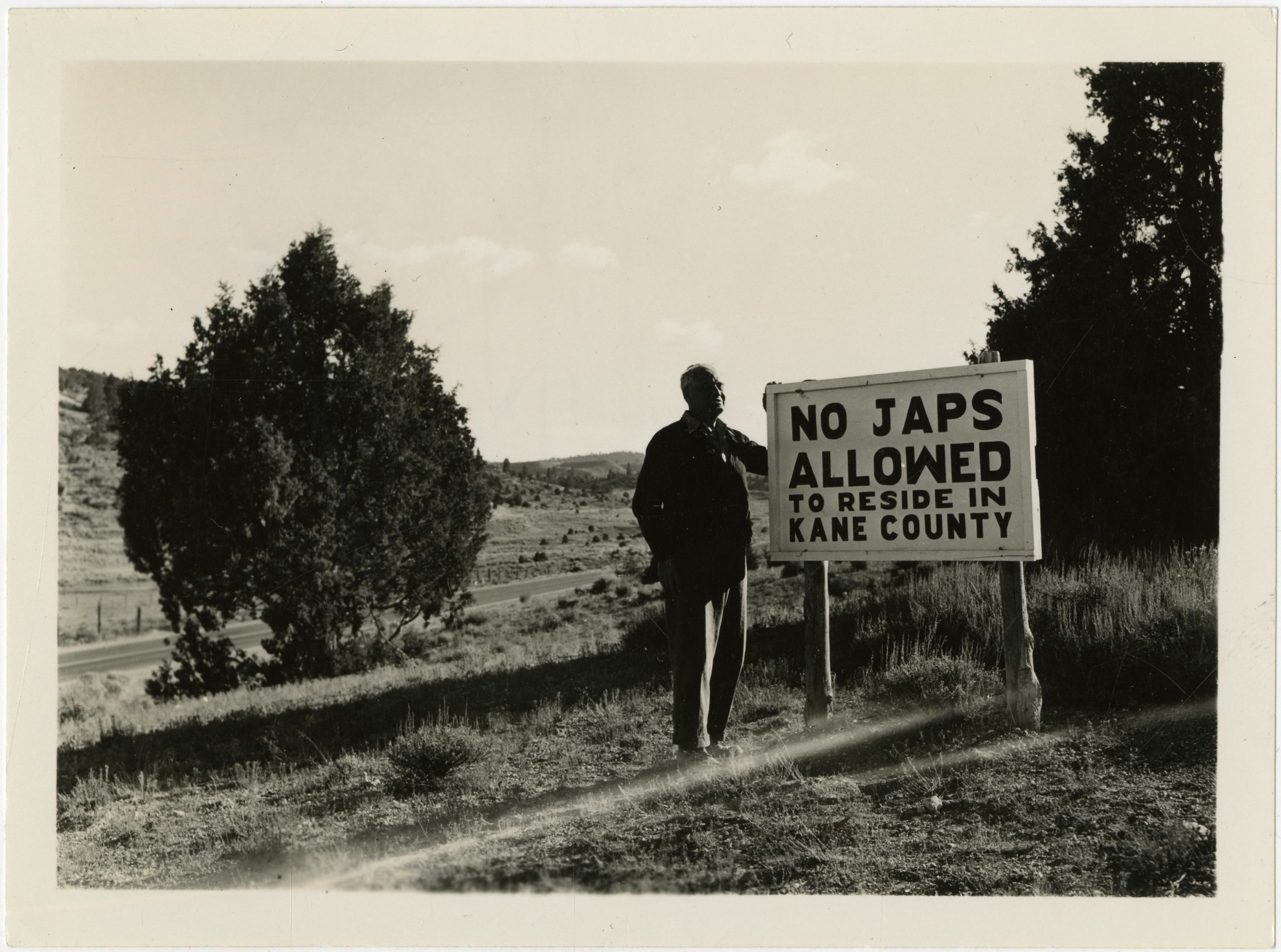

[Header: Old man standing beside Utah highway sign of circa 1945. “No Japs Allowed to Reside in Kane County.” Courtesy of the Carl Weeks Photograph Collection, The University of Utah.]