March 17, 2022

Karen L. Ishizuka is a writer and chief curator of the Japanese American National Museum. In response to our Women’s History Month writing challenge—in which we ask writers to share the actions and emotions elicited by photos of women in the Densho archives or their own collections—she takes a closer look beneath the sunny surface of a government photo of her aunt at the Santa Anita Assembly Center, revealing how it “conceals more than it shows.”

Why, Oh Archive?

Rather than “Answering the Archive,” I’d like to ask, “Why?”

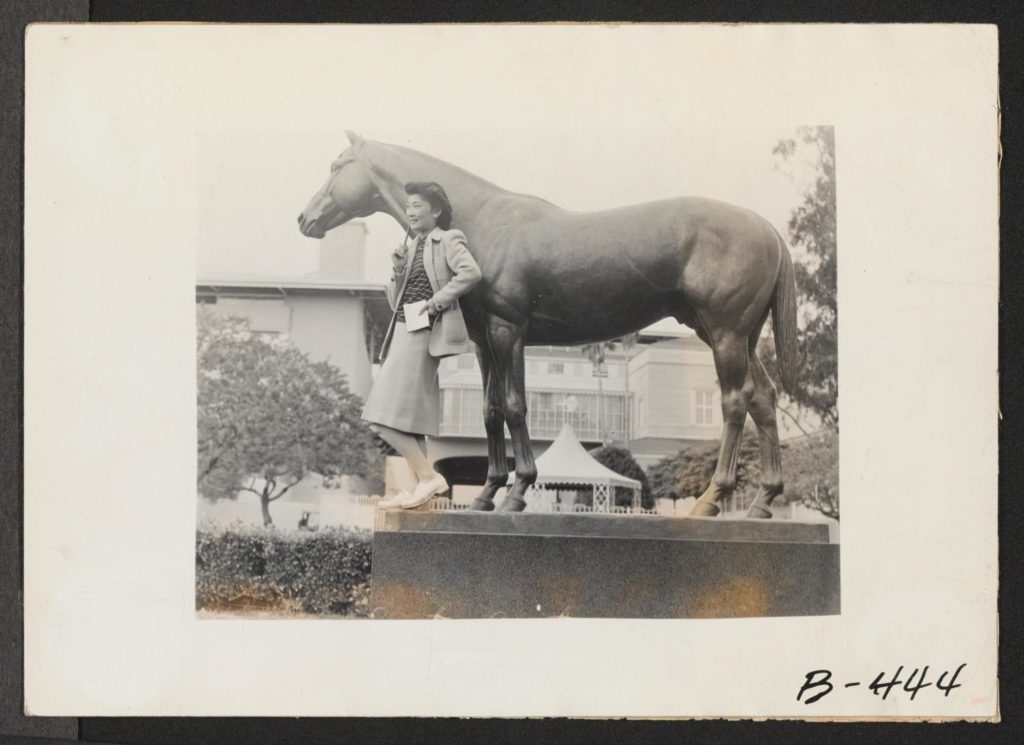

We know the “what,” or at least partially. The caption of this War Relocation Authority photo reads: “Mrs. Lily Okura poses with a statue of Seabiscuit in Santa Anita Park, now an assembly center for evacuees of Japanese ancestry.” It was taken by Clem Albers on April 6, 1942.

Yet this is a photo that conceals more than it shows. That in just seven days, the race track/park was turned into the longest-running temporary detention center holding Japanese Americans before they were sent to permanent camps across the country. That my Auntie Lily, along with her husband, another uncle, two other aunts, and my grandmother lived in a horse stall—like the champion racehorse Seabiscuit’s—with 8,500 other Japanese Americans. That my grandfather had been arrested by the FBI the night of December 7, 1941 and was—on the day this photo was taken—imprisoned at Fort Missoula, MT, after which he was sent to Fort Sill, OK; Camp Livingston, LA; and Santa Fe, NM before allowed to join his family in the Jerome concentration camp in Arkansas. That just out of frame in the parking lot were 500 newly erected barracks to hold the 10,500 others who couldn’t fit into the horse stalls.

But why was Lily, who had been a dancer and one-time understudy for Anna Mae Wong, hoisted onto the platform and posed with the legendary horse? Neither a journalist or a writer, why is she holding a notebook in one hand while the other seems to be holding a pen to her chin, as if coyly pondering what to write? And, rendering the photograph even more staged, genderized and odd, why is she (coyly) raising her left heel as if modeling her modest, yet stylish outfit while posing with this archetypal symbol of American virility? Had I only found this photo while Auntie Lily was alive. Now I can only lament, why, oh Archive?

—

Karen L. Ishizuka is a sansei descendent of Manzanar and Jerome concentration camps. Presently chief curator of the Japanese American National Museum (JANM), she is author of Lost & Found: Reclaiming the Japanese American Incarceration, Serve the People: Making Asian America in the Long Sixties and co-editor of Mining the Home Movie: Excavations of Histories and Memories. Her essay on art about the WWII incarceration — “Art Saved Us … from What?” — was recently published in Are the Arts Essential?

Read the rest of this series:

Nikiko Masumoto, “How to Wonder”

Brynn Saito, “What Exists Outside the Frame”