November 30, 2023

Guest opinion essay by Maggie Tokuda-Hall. Densho publishes guest opinion essays that draw meaningful connections between the incarceration story and the present, and that promote equity and justice today. Learn more about our work and mission here.

When I wrote Love in the Library, the true story of my maternal grandparents who met in a Japanese American incarceration camp during WWII, I did not start the story with Pearl Harbor. I made this choice on purpose. Leading with the state line of justification for the deep injustice that followed is, in my opinion, a mistake with several insidious repercussions. To start, a justification for the unjustifiable will always minimize the cruelty, absurdity, and violence of the disproportionate reaction. It will also minimize the pain of survivors — sure you were uncomfortable, but what was the US supposed to do, not defend itself? — and treat their lives as acceptable collateral damage. It will also occlude the climate of injustice and racism that preceded it. As if Japanese Americans had been whole-heartedly embraced by the American community until their ancestral nation attacked us; a claim that would be both ahistorical and deeply naive.

This is not a decision I made with the intention of brushing aside the American deaths on December 7th as if they did not matter. Of course they do. But mourning and the honest recounting of history are things that can happen simultaneously, or entirely separately. These are not mutually exclusive practices. And when we recount history, we are learning to understand that the pain of marginalized people can no longer be ignored. Grave injustice can always be rationalized in the moment, though it can rarely bear the scrutiny of even a vague attempt at rigorous hindsight.

Still, nearly every professional trade review of Love in the Library began with “After the attack on Pearl Harbor…” It was so consistent. And it felt like such a misunderstanding of what the book had set out to do, which was to humanize the people whose lives were cruelly upended. To situate my grandparents’ WWII incarceration within the deeply American tradition of racism that began long before Pearl Harbor. They were just a student and a pharmacist. They bore no responsibility for that attack, and so it was not the focus of the book about their love.

Has my book failed? Sometimes I think it has. Because many of the same people who honored me for my work in that book refuse to call for a ceasefire in Gaza now. Have come into my DMs to lecture me or “educate” me about why this unfathomable loss of life is justifiable. Email me to rationalize it.

It is worth mentioning that I am also a Jew. I was raised a Zionist. I was told that the Israeli flag was the Jewish flag, and I believed it. I went to Hebrew school from kindergarten until my Bat Mitzvah, where Zionist ideology was even more entrenched. Like many Jews of my generation, I understood that asking the wrong questions about Israel or daring to ask whether or not it was a good idea was something that would end in your elders yelling at you. I bear the unfortunate personality flaw of being deeply averse to conflict, particularly within my family, and so I said nothing, even as my own ideology began to diverge wildly from that with which I was raised, a process that began in college and only deepened as I aged. I understand now the price of my own cowardice, which is that now it is a shock to many around me that I hold the views I do. And that I have failed them and myself, denying us all the opportunity to discuss these things while emotions were not running quite so high, while the stakes were not so desperate.

It is with these two facets of my own identity in harmony that I feel a deep sense of obligation to speak clearly about what is happening in Gaza right now. Which is that it’s genocide. That the Nakba which started in 1948 has simply never ended. And that it stands in opposition to my values as a Jew, and also as a Japanese American. Our words, our framing around this issue, matter. Because it is only with international pressure that Israel will end its wholesale slaughter of civilians, of children.

Never once have I seen a recounting of Kristallnacht preceded with a statement condemning the murder of a German politician by a Jewish student, the inciting incident that was used as justification at the time.

Yet time and time again, we see the demand manifest that all statements about the genocide unfurling in Gaza be proceeded by a statement condemning the attacks on October 7th. And even now I feel myself wanting to be clear; they were terrible. It was a war crime. The descriptions of what happened made me sick to my stomach, and I wept as I took in the news. But to lead with this even now, as the Palestinian death count has ballooned to an order of magnitude far greater than the loss of life that day is increasingly becoming a bit of political theater that only serves to minimize the ongoing and unimaginable suffering of the Palestinian people. To justify it. But all that death is unjustifiable.

As Vivian Silver, an Israeli peace activist who was killed by Hamas on October 7th, has said: “You can’t cure killed babies with more dead babies. We need peace.”

And yet here we have more and more dead babies. Whether they died to famine or bombs or bullets or in the incubators that lost power, babies — surely the most innocent, surely those whose lives we can most blamelessly defend — are killed. I open Instagram to see a video of a father cradling a baby who does not move. I check my email and there, in that same glowing rectangle, are body bags, each with someone’s beloved inside, organized in neat lines. A mother holds on to a child’s body, shrouded in white, stained with red. Gone. She weeps and I weep. It does not take a political genius to know that this will not bring peace. And it does not take an astute observer to understand that, at this point, there is no innocent Palestinian in the eyes of Israel’s military. Just as there was no innocent Japanese American in the USA during WWII. Just as there is no innocent Black life in the USA now. Just as there was no innocent Jew in Nazi-controlled Germany.

There is always an attempt at justification. There is always a rationalization. But understanding history, and particularly from the point of view of the marginalized, demands that we not accept those lines of reasoning in the present. There is no need for us to wait for hindsight to render these explanations toothless. We should know enough to understand that violence like this never occurs within a vacuum. There is always context. And a near century of increasingly brutal occupation is the context here.

Palestinians need not perform their blamelessness in order to have lives worth saving.

I think of the Loyalty Questionnaire given to all incarcerated Japanese Americans over the age of seventeen, which demanded in questions 27 and 28 that they declare their loyalty to the United States, and also state their willingness to serve in the armed forces. Approximately 12,000 of the so-called “no-no boys” refused to give an unqualified “yes,” and were labeled by the War Relocation Authority as “disloyal.” And I admire them for it.

I think of Ansel Adams’ photography in the camps, determined to show happy, smiling, resilient Japanese American faces. He knew he was documenting an injustice, and wanted to show the world it was wrong. But he wanted us to perform our blamelessness, and staged it so that we would. So well meaning, and also so condescending. That we should require a veneer of happy suffering in order to be considered human. That we should be required to accept our abuse with a grin. There are no photos of our ancestors getting tear gassed and shot in Manzanar. No videos of us protesting in Tule Lake. But these things happened. Would that disqualify us from empathy?

We understand now, with the benefit of hindsight, how cruel these demands were. We should also understand that it would be just as cruel to demand it of someone else, who is facing annihilation. We should be able to see their humanity with the exact clarity with which we wish others had seen ours. On Kristallnacht. On December 8th. All these incidents are different in important ways, but the events that followed share a common theme: the complete abandonment of justice.

There is simply no reasonable rationalization for injustice.

There is only the will to do cruelty in the world, and the indifference of those who bear witness.

—

Maggie Tokuda-Hall has an MFA in creative writing from USF. She is the author of the 2017 Parent’s Choice Gold Medal winning picture book, Also an Octopus, illustrated by Benji Davies. The Mermaid, the Witch, and the Sea is her debut young adult novel, which was an NPR, Kirkus, School Library Journal and Book Page Best Book of 2020. Its sequel, The Siren, The Song and The Spy came out in September 2023. Her graphic novel, Squad, is an Ignyte and Locus Award nominated comic book, and her newest picture book, Love in the Library, has been named a Best Picture Book of 2022 by Book Page, School Library Journal, Booklist, and Publisher’s Weekly. She lives in Oakland, California with her husband, children, and objectively perfect dog.

Maggie joined Densho at our 2023 virtual fundraiser, “Our Voices Will Not Be Silenced,” to share how Scholastic, Inc. attempted to censor terms like “racism” in her Love in the Library author’s note, what this tells us about increasing attempts to whitewash our history, and how we can collectively push back. Watch Maggie’s keynote conversation here.

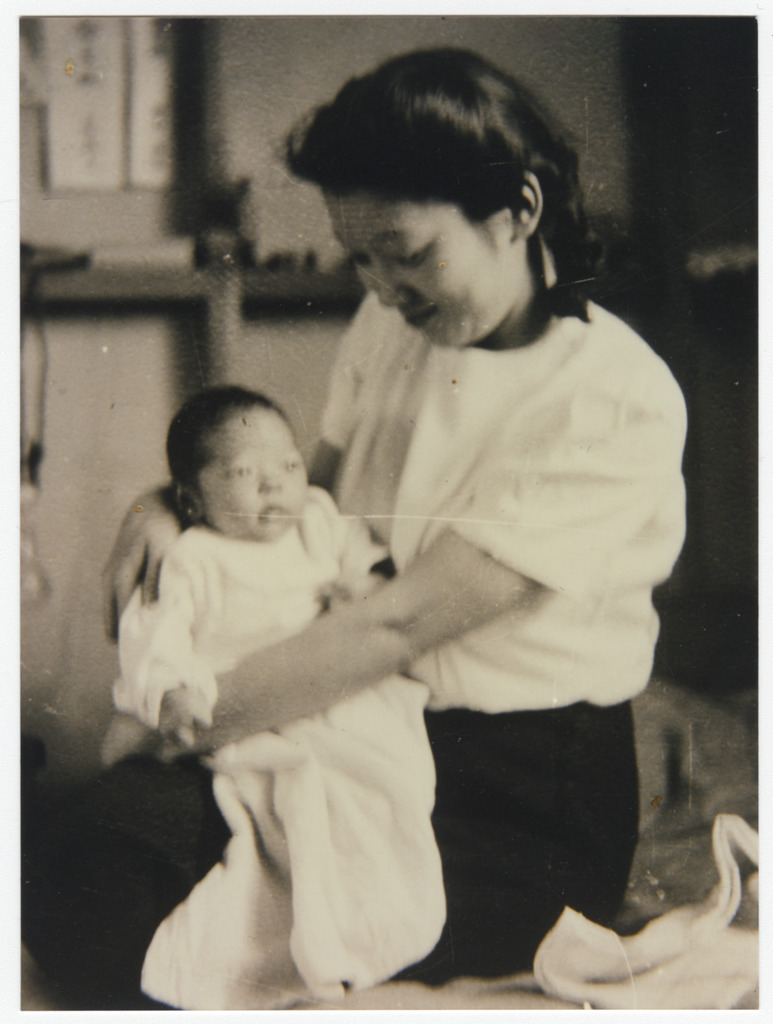

[Header: Maggie’s grandmother Tama Inouye Tokuda (far right) at the Puyallup Assembly Center in 1942. Courtesy of the Tokuda Family Collection, Densho.]