June 13, 2022

In this guest post, Kathryn Tolbert, creator of the oral history archive The War Bride Project, shines some light on the experiences of Japanese immigrant women in Montana through the story of one picture bride pioneer.

In November 1915, a well-dressed woman got off the train from Seattle at Whitefish, Montana. She was accompanied by her new husband, one of the town’s most prosperous businessmen, Mokutaro Hori.

Aya Hayashi Hori’s arrival in Whitefish was an important crossroad in a long life that began in Japan in 1882 and ended in Montana 90 years later. Over her lifetime she navigated the treacherous terrain of xenophobia, economic instability, and heartache. She embraced the United States as her home yet cherished her Japanese culture, finding a delicate balance that allowed her to both thrive in the United States and, eventually, offer support to other young women from Japan. Aya’s story reveals how historic forces and personal choices shaped an Asian immigrant woman’s experiences in the West.

Two Times a Picture Bride

Aya was part of a wave of Japanese women emigrating to the United States at a time when male laborers from Japan were barred from entry. The Japanese men already living in the country were allowed to bring wives, so families exchanged photographs, arranged marriages by proxy, and thousands of such women came as “picture brides.”

She first arrived in America in 1911 in Tacoma, Washington as a picture bride to Tanekichi Kimura, a dock merchant working with Japanese ships entering Tacoma’s Commencement Bay. Just two years later, an autumn squall caught Aya’s husband while on a rowboat for work. The boat overturned and he drowned.

When the widowed Aya saw an ad asking for a Japanese wife in a West Coast Japanese language newspaper, she sent her photograph. Mokutaro Hori, who posted the ad, was an esteemed figure in Whitefish, Montana, having become a successful rancher, produce grower, and restaurateur.

Aya and Mokutaro married on November 10, 1915 at the Japanese Methodist Episcopal Church in Seattle. The Whitefish Pilot reported on the front-page social column, “A telegram was received in the city yesterday by friends of Mr. Hori’s, stating that he and Miss Hayashi, of Seattle, and formerly of Japan, were married and would arrive in Whitefish within a few days. Congratulations will be in order upon their arrival.”

Details about the couple’s lives in Montana were described in a series of interviews conducted in the 1990s by a local historian, Mary Tombrink Harris, who spent her early girlhood on the Hori ranch. From her accounts, the Horis moved comfortably in Whitefish society, straddling the divide between Japanese immigrants and white Americans. They employed both whites and Japanese in the Hori Café, though Mr. Hori acknowledged the racial divide by putting whites in most of the front jobs, such as cashier and waitress. Japanese and non-Japanese laborers worked on the ranch, and local high school students found part-time jobs picking and packing vegetables.

In 1931, Mr. Hori fell ill with stomach cancer and died at the age of fifty-eight. In his will he donated five lots to the city of Whitefish. A plaque at City Hall today pays tribute to the couple “for their community interest, support, and generous gift of real estate to the city of Whitefish.”

Navigating Wartime Tensions

Aya was once again a widow, and still a non-citizen immigrant, but initially her place in Whitefish society sustained her. She continued to manage the business and was an integral member of the community, even hosting the wedding reception for Whitefish High School principal Ralph Tate and his bride, Helen Jones, who recalled, “With Japanese students serving the delicate refreshments, and Mrs. Hori giving us a beautiful hand-painted china plate, the occasion was indeed memorable.” She continued to entertain community members in her apartment above the café.

But as the smoke poured from mangled battleships in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Japanese Americans across the United States became targets of retribution. Aya’s deep ties to Whitefish and the respect she’d earned among locals initially shielded her from harm, but the prominent Japanese business in the center of town was eventually too much for hot-headed men looking for revenge. Art LaBrie, part owner of Art & Ernie’s Fountain Lunch in Whitefish, described what happened in the spring of 1942:

“The day that that bunch came, pretty near raided the [cafe, and] broke everything up. They just ruined the place. The next morning, I was in the back of my place… and she says, ‘I have to close up.’ I said, ‘What’s the matter, Mrs. Hori? Can I help you?’ .… Those boys came back and they were hot. ‘They told me, close em up.’ So she says, ‘You come and I give you everything I’ve got, bacon, salt, sugar – I’ve got everything. You can have it all.’ I says, ‘Mrs. Hori I want to pay you.’ She says, ‘No pay. No pay.’ That’s when she closed.”

Aya was frightened into a hasty sale and received only a fraction of what the business was worth, according to Harris.

The End of Asian Exclusion

The end of the war brought a positive turn to Aya Hori’s life. Recently widowed Jiro “Jim” Masuoka of Kalispell, an oiler and brasser for the Great Northern Railway, courted her, and the couple married on February 22, 1949.

Around this time, the total exclusion of Asian immigration began to crumble, driven in part by pressure from couples in love. The War Brides Act of 1945 expedited visas for British, Australian and New Zealand women married to US servicemen, but Japanese were not included. Congress passed hundreds of private bills that allowed individual Japanese women married or affianced to Americans to enter the country. Then, in 1947, President Truman signed a bill that gave US servicemen a thirty-day window to complete paperwork that allowed them to marry and bring Japanese wives to the United States. According to a newspaper account, 831 couples navigated this administrative strait. Among them was Aya Hori’s son, Toshio, who married Yoko Yamaoka in that brief opening. In 1948, he brought her home to Whitefish, where they lived for about a year before settling in Washington state.

Finally in 1952 the outright exclusion of Asians came to an end, although a complete lifting of racial restrictions would not be accomplished until 1965. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, also known as the McCarran-Walter Act, permitted limited immigration from Asia under a quota system and eliminated race as a basis for naturalization. Aya Hori Masuoka wasted no time in applying for citizenship and became a U.S. citizen on June 11, 1953, at the age of 70.

In the next two decades she befriended the newest Japanese immigrants, the war brides who had married U.S. servicemen in Japan after the war. In and around Kalispell, the young women quickly found one another, and often made their way to Aya Hori Masuoka. Aya welcomed them into her home, where her kitchen was stocked with familiar Japanese basics—bonito shavings for broth, seaweed, soy sauce, rice, and dried matsutake mushrooms. In this way, she showed them that they did not have to relinquish all of their Japanese identity as they became Americans.

Aya Hori Masuoka died in 1972 at the age of 90. A simple granite marker in Kalispell’s Conrad Memorial Cemetery records her passage. In a life stretching from the era of picture brides through that of war brides, her experiences point to the significant role immigrant women played in shaping American attitudes. Throughout that time, Aya remained an elegant Japanese lady, but also pledged allegiance as an American citizen and made her home in Montana. She demonstrated that becoming American did not require her to forsake her heritage. In her relentless capacity to make the best of her immigrant circumstances, she forged a full life.

—

Kathryn Tolbert is a journalist, most recently with The Washington Post. She co-directed the documentary film Fall Seven Times, Get Up Eight: The Japanese War Brides and created an oral history archive of the stories of Japanese war brides and their families at www.warbrideproject.com.

Thanks to Montana The Magazine of Western History for permission to reprint this excerpt from an article originally published as: Kathryn Tolbert, “A Japanese Picture Bride in Montana: The Story of Aya Hori Masuoka (1882-1972), Montana The Magazine of Western History 70:1 (Spring 2020): 27-43. The original article can be read here.

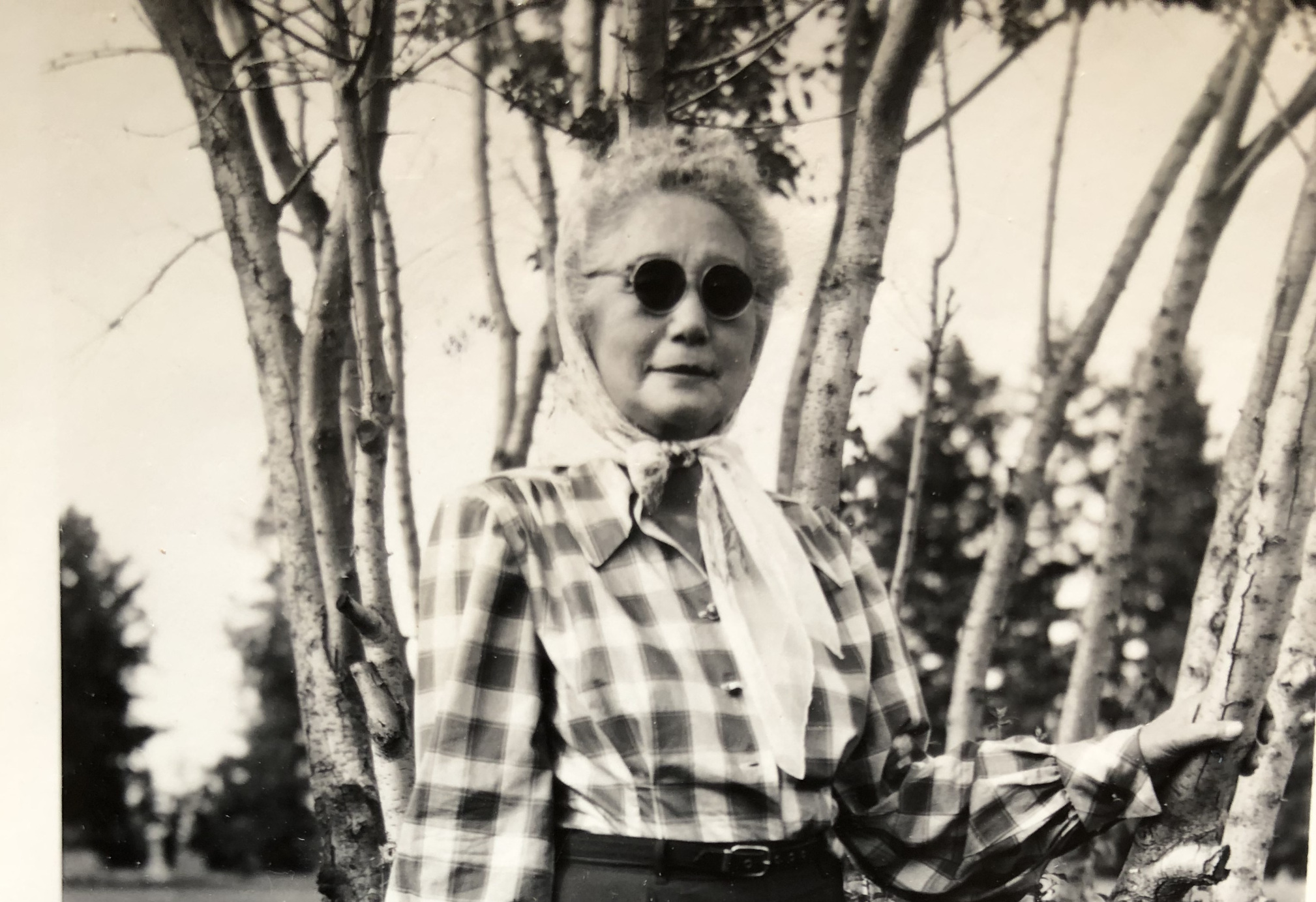

[Header: Aya Hayashi Hori Masuoka in the 1960s. Courtesy of Esther Premo and Judy Aya Williamson.]