August 4, 2021

Early in the morning on August 6, 1945, an American warplane cut through the cloudless sky over Hiroshima and dropped a single, devastating bomb, obliterating the hospital directly below the “Little Boy’s” path and much of the surrounding city. Three days later, as Hiroshima still burned, a second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. At least 100,000 people were killed instantly in both attacks, and many more died of blast injuries or radiation sickness in the weeks and months that followed.

In a cruel — and often unacknowledged — twist of irony, among the nearly half a million atomic bomb victims and survivors were thousands of Japanese American citizens of the United States.

No conclusive number indicating just how many Japanese Americans were affected by the atomic bombings exists today — although an estimated 11,000 people born in Hawai`i or the United States were in Hiroshima alone. More pre-war Japanese immigrants came from Hiroshima than from any other prefecture. Nagasaki also sent a high number of immigrants to the U.S. It was a common practice for these Issei immigrants to send their U.S. citizen children to Japan to visit relatives and receive a Japanese education, and many Japanese Americans were stranded in Japan when war broke out in 1941. Consequently, thousands of Nisei and Kibei children of Japanese immigrants were in their parents’ hometowns of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during the attacks, and became war casualties of their own birth country.

Approximately 3,000 Japanese American survivors of the two atomic bombings returned to the U.S. after the war. They were soon followed by Japanese citizens who migrated as war brides, or simply as immigrants seeking better opportunities than post-war Japan could offer.

Despite sharing a common identity as hibakusha — literally “bomb impacted people” — these U.S. survivors had vastly different experiences. For some, their arrival in America marked a much anticipated return to their home and their families, while others came as war refugees displaced from the only home they knew. Even American citizens like Yuriko Furubayashi, born in Waimea, Hawai`i in 1927 and sent to live in Japan when she was 10 years old, struggled to adapt. “I was in Japan ten years, so my English was so bad,” she told historian Naoko Wake in a 2013 interview.

As American hibakusha began to (re)settle in the United States and rebuild their lives, one thing that did remain universal was a lack of medical care and community support. Unlike in Japan, where the government began to provide medical treatment and monetary support for hibakusha in the 1950s and 1960s, survivors in the U.S. were not recognized by either government. Most had left Japan earlier, when hibakusha were still highly stigmatized and denied any government assistance. With no resources available to them, they had little motivation to come forward as atomic bomb survivors living in the country that dropped the bomb.

As Wake notes in “Surviving the Bomb in America: Silent Memories and the Rise of Cross-national Identity,” their ability to speak out — or rather, the American public’s willingness to listen — was further strained by Cold War narratives that framed the U.S. as a benevolent champion of democracy taking a newly docile, but still suspect, Japan under its wing: “Many Americans believed that the war begun by Japan with Pearl Harbor ended appropriately with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Survivors were not victims who deserved sympathy, but those who shared in Japan’s deserved punishment.”

“They’re thinking about American soldiers, save the life for the soldier,” Kibei survivor Izumi Hirano said in a Densho interview.

The message to American hibakusha was that they should consider themselves lucky to be in the United States, and to keep quiet and not make waves if they wished to remain so.

Even with these barriers, U.S. hibakusha began to come together and break their silence in the 1970s. They organized small gatherings in Los Angeles and San Francisco, and eventually formed the Committee of Atomic Bomb Survivors in the United States of America (CABS) — now the American Society of Hiroshima-Nagasaki A-Bomb Survivors — in 1971. Their first major campaign, launched in 1974, called on the California state legislature to pass a bill that would create medical programs for all U.S. residents suffering from radiation. A similar proposal in 1978 brought their demands to Congress, with a federal bill calling on the government to fund survivors’ medical treatment.

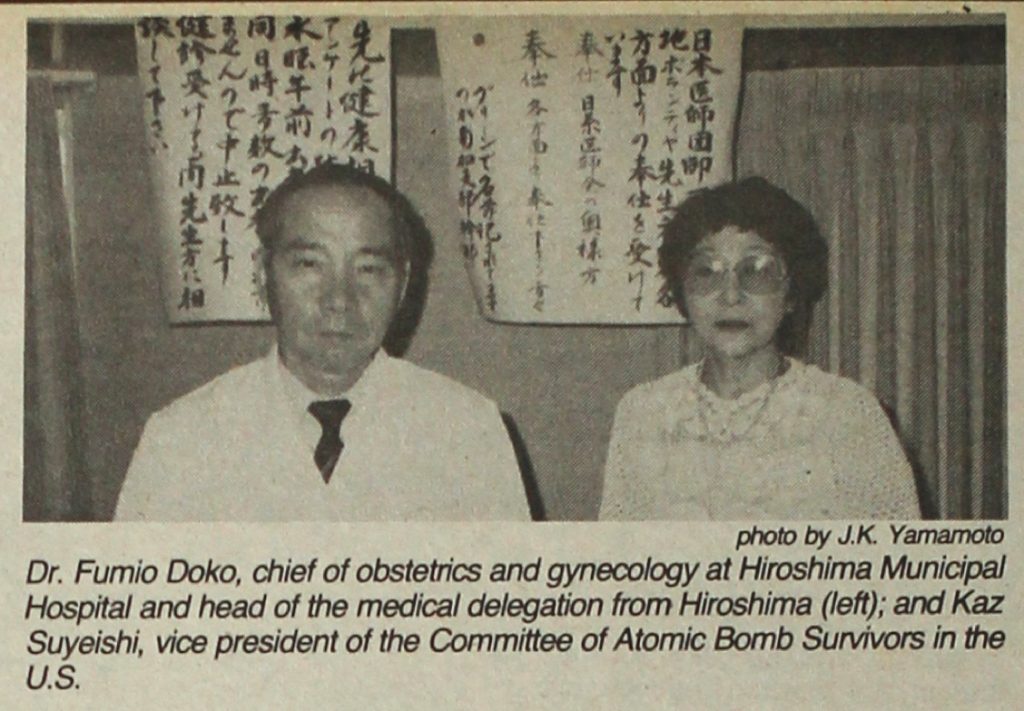

Issei and Nisei women took on a prominent role in this hibakusha activism. Kaz Suyeishi, a Nisei survivor, served as vice president of the L.A. chapter of CABS and was instrumental in both crafting the proposed legislation and putting pressure on elected leaders to bring it to a vote. In preparation for a hearing on the 1978 bill, Suyeishi recruited local Issei to attend and worked with the JACL to charter buses to provide transportation from Little Tokyo — ensuring that the hearing room was packed with a visible show of community support.

The two bills ultimately failed when representatives refused to vote on legislation that would hold the United States culpable for consequences of its “legitimate” wartime actions — but survivors continued to organize through the 1970s and 1980s. In 1977, CABS brought physicians experienced in treating radiation from Hiroshima to Los Angeles and San Francisco. These medical check-ups — which continue today — were repeated every two years, open to anyone affected by the bomb regardless of citizenship, ethnicity, or nationality.

These survivor-led coalitions were joined by supporters from the Japanese American community, who helped establish medical clinics, staff the biennial check-ups, provide legal advice, and publicize their cause. Survivors of U.S. concentration camps drew a connection between the hibakusha’s efforts to obtain recognition from the U.S. government and their own budding redress movement. And young people involved in the Asian American and anti-war movements helped place the hibakusha’s activism within a larger context of Third World solidarity against U.S. imperialism.

Today, there are fewer than 1,000 known American hibakusha. Though they receive medical care and some compensation from the Japanese government, the United States still offers no recognition or support. But despite their limited gains, these survivors’ advocacy and courage in coming forward deserves to be honored as a pivotal piece of American history — and a reminder that the lasting consequences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are an undeniable part of that history.

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Communications Coordinator

For more on U.S. hibakusha, read Naoko Wake’s Densho Encyclopedia article on Japanese American hibakusha and published book, American Survivors: Trans-Pacific Memories of Hiroshima & Nagasaki (Cambridge University Press, 2021), Gloria Montebruno Saller’s forthcoming American Citizens as Survivors of the Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima (Routledge), and Tom Coffman’s Tadaima! I Am Home: A Transnational Family History (University of Hawai`i Press, 2018).

Wake has also conducted dozens of oral history interviews with Japanese and Korean American hibakusha as part of her research; some of which are available in the Densho Digital Archive.

[Header image: A Japanese child looking at a building destroyed in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, c. April 1947. Courtesy of the Shiuko Sakai Collection, Japanese American Museum of Oregon.]