November 15, 2017

The Vietnam War, which officially commenced on November 1, 1955 and lasted for nearly twenty years, cost the lives of over 58,000 Americans and more than 3 million Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Lao soldiers and civilians. The peace movement that gradually turned public opinion against the war is often remembered as an affair led by white college students, white flower children, white pastors, and white mothers, with perhaps a smattering of black and brown faces somewhere in the background. But Asian Americans and other people of color played an integral, and frequently independent, role in the anti-war movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

‘Til now: a movement spread out and spread thin’

By 1969, one out of every two Americans personally knew someone who had been killed or wounded in Vietnam. Up to 40,000 men were drafted each month, and casualties—most of them civilians—had reached a staggering million-plus. Consequently, it was around this time that the peace movement also reached its peak.

But it would be a mistake to understand this as a single moment in time isolated from larger social and cultural shifts. Opposition to the Vietnam War was a key component of the Asian American Movement, and grew out of the same groundswell of activism that resulted in the birth of Asian American Studies, the Asian American women’s movement, and redress for the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans. As Karen L. Ishizuka notes in her study of “the Movement”: “It was no accident that Asian America was born at the peak of the Vietnam War.”1

The post-WWII generation of Asian Americans—including many Sansei influenced by their parents’ wartime incarceration and keen to break the silence around historical and contemporary injustice—had grown up against a backdrop of U.S. imperialism in Asia and come of age as the Vietnam War reached its bloody climax. Bruce Iwasaki, writing for Gidra in January 1973, explained:

“The U.S. involvement in Vietnamese affairs began around the time we were born; stayed hidden from the national consciousness during our years of innocence; escalated as we matured; and has reached climactic proportions while our generation gains the will and seeks the means to end that involvement. Much as we forget, ignore, or grow numb to it, the war has been a constant shadow in our lives.”2

Activists young and old had long organized against discrimination at home, but Vietnam globalized the movement and helped to unify different ethnic Asian groups under a common cause. Violence in Southeast Asia—linked to historical atrocities in the Philippines, Korea, Japan, and Okinawa—gave Asian Americans the language to talk about their own experiences here in the United States. Centuries of Western colonization and exploitation in Asia was responsible not only for the war against their “cousins” in Southeast Asia, but for the diasporas that brought their immigrant ancestors to America, for the inherited trauma of state-sanctioned violence at Manzanar and Rock Springs, for the “dehumanizing conditions in our Asian communities, barrios, black ghettos and reservations.”3

A movement previously “spread out and spread thin”4 across a wide spectrum of localized causes, divided along the lines of ethnicity, nationality, language, and geography, gained strength as Asian Americans increasingly positioned themselves as members of a “global community of Asians opposed to U.S. imperialism.”5 Concurrent struggles, like the fight for ethnic studies on college campuses and gentrification of Manilatowns, Little Tokyos, and Chinatowns, were no longer isolated problems but part of a larger campaign against colonization and white supremacy.

‘Even the peace movement is infected with the disease of racism’

This borderless, multiethnic political identity directly informed Asian American resistance to the war. Like the Black Panthers, the Brown Berets, and other “colony-community” coalitions, Asian Americans recognized that protesting the war in Vietnam meant protesting the war at home.

But the mainstream peace movement, dominated by white liberals and colorblind socialists, was reluctant to adopt an explicitly anti-racist platform. Their opposition to the war was frequently defined by an inflexible, single-issue focus on bringing home “our boys,” and paternalistic sympathy for the poor, hapless “Indochinese” being slaughtered overseas did not extend to support for an independent Vietnam.

Asian Americans were “roundly rebuffed… as divisive and distracting” when they called on white allies to address the disproportionate deaths of black and brown soldiers in Vietnam and the specifically anti-Asian nature of the war.6 Activist Steve Louie recalled, “the broader movement had a hard time with the Asian movement, in some ways. Because it broadened the issues out beyond where they wanted to go, beyond what a lot of people wanted to deal with: the whole question of U.S. imperialism as a system, at home and abroad.”7

Tired of being tokenized and dismissed by white peaceniks, Asian Americans—along with Black, Chicano, and Indigenous activists—soon began to build an independent movement where they could interrogate the racism and colonialism of the war on their own terms. These “Third World” coalitions continued to lend support to the broader anti-war movement, but internal tensions sometimes rose to the surface in visible rifts.

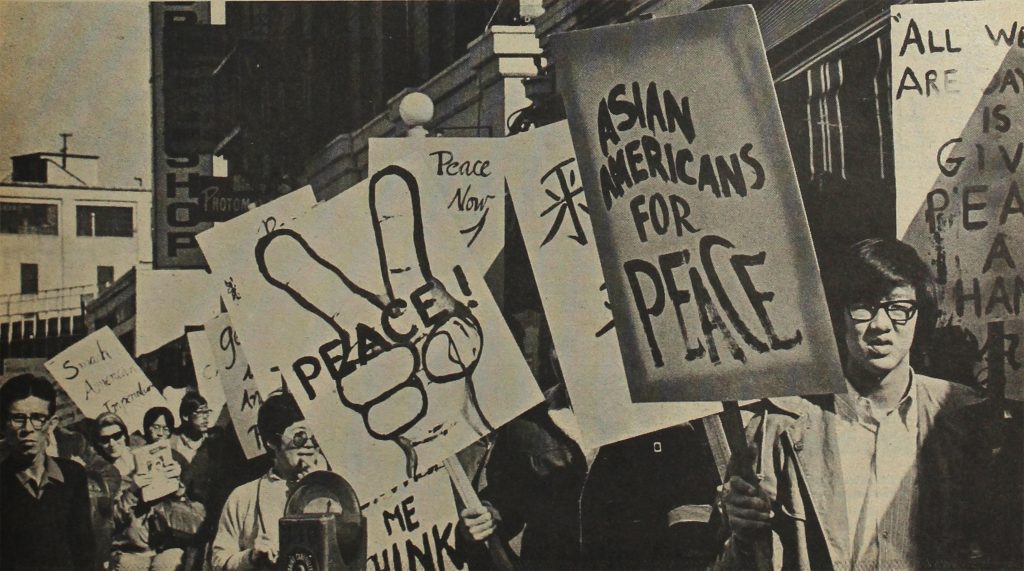

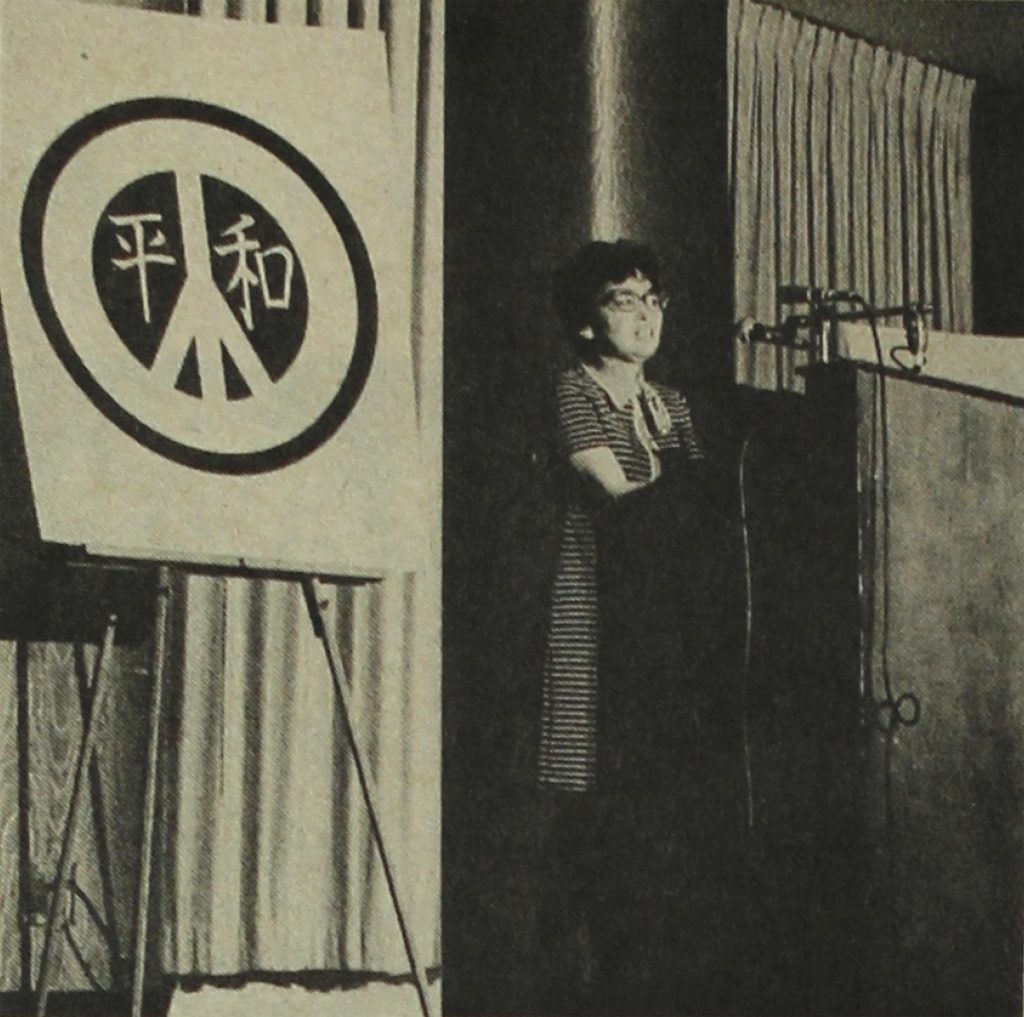

At rallies like the 1969 moratoria and the famous April 24, 1971 March on Washington, demonstrators marched in separate Asian contingents carrying bilingual signs and chanting slogans that clearly articulated the war’s racial overtones: “Stop killing our Asian sisters!” “End your racist war!” “Asia for Asians!” During an international women’s conference in April 1971, white feminists were excluded from some meetings after referring to the Vietnamese and Lao delegates as “our little Indochinese sisters” and “show[ing] overt resentment” to discussions of race and class.8

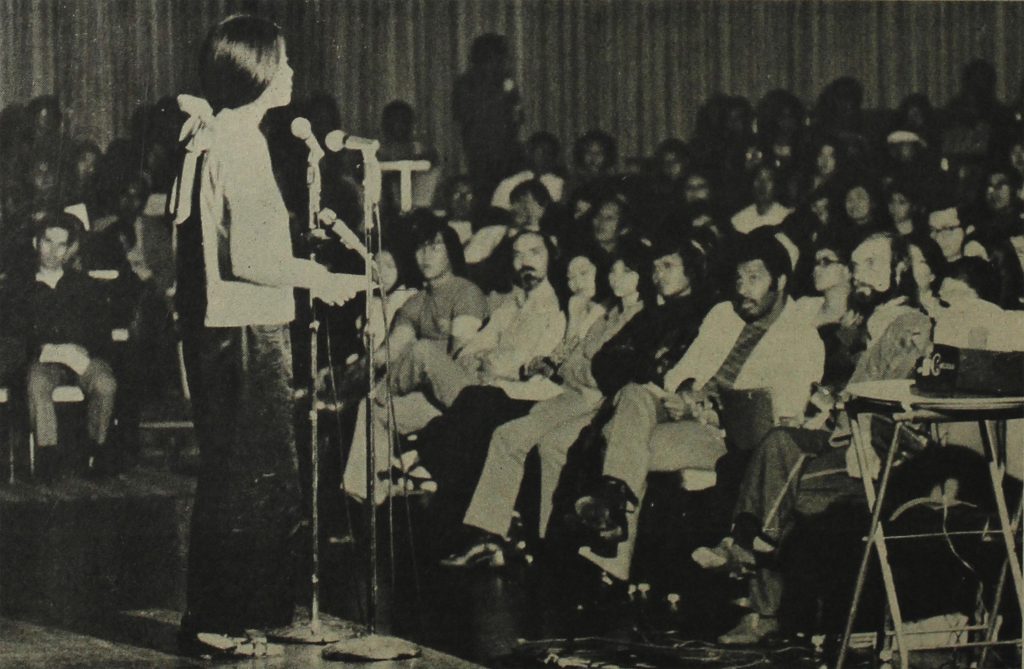

In some cases, activists used more confrontational tactics to get their point across. After being refused speaking time by white organizers at an April 1971 march in San Francisco, the Third World Contingent—including 300 Asian Americans—staged a takeover, shoving their way onto the platform and forming a protective barrier around Patsy Chan while she implored the crowd to “smash imperialism from within.” At a January 1973 demonstration led by the National Peace Action Coalition, the Los Angeles Asian Coalition walked out in protest of “the racism and paternalism that exists within the white anti-war movement.” Soon after, they called for a boycott of future NPAC-sponsored events over its refusal to confront their “white skin privilege” and broaden their message beyond concern for American lives.9

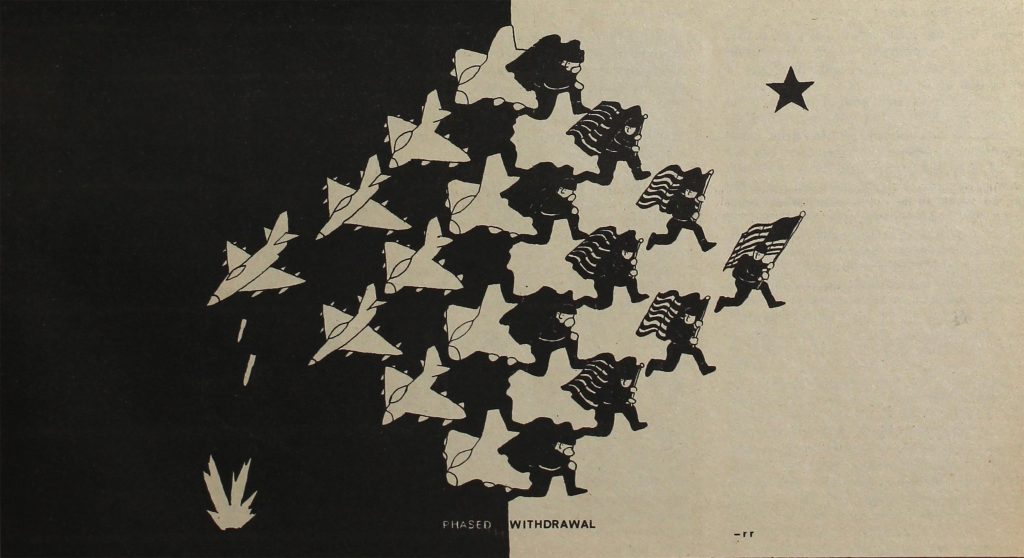

The mainstream peace movement began to dissipate as the Nixon administration implemented its “Vietnamization” policy in the early 1970s. By reducing the number of U.S. ground troops in Vietnam while shifting the burden of combat to South Vietnamese forces, American casualties began to decline. For those whose primary objective had been to bring back the troops, there was no longer much to protest.

But withdrawing combat troops (while simultaneously increasing airstrikes and continuing political interference throughout Southeast Asia) did nothing to address “the reality that the worst thing about the war is that Asian people are being uprooted and murdered daily.”10 For many Asian Americans, the lack of public outcry over the rising death toll for Vietnamese soldiers and civilians—not to mention the “secret war” in Cambodia and Laos—reflected the white anti-war movement’s disregard for Asian lives and freedoms.

‘We are gooks in the eyes of White Americans’

Asian American opposition to the Vietnam War, like the larger Asian American movement it grew out of, was heavily influenced by the radical politics of Black Liberation. “Over-thirties” like Yuri Kochiyama and Kazu Iijima had cut their activist teeth in the civil rights movement, while many young people began organizing against the war after participating in the Third World Liberation Front strikes—which had been initiated by Black Student Unions at San Francisco State and UC Berkeley. Community groups like the Red Guard Party adopted the Black Panthers’ signature beret and recreated their free breakfast program for Chinatown youth. Asian Americans also borrowed the language of Black activists, translating Black Power into Yellow Power and declaring, “No Vietnamese ever called me chink.”

But for Asian Americans—the only racial group in the U.S. with the face of “the enemy”—the war was also deeply personal. Asian Americans opposed the war “not only from what we knew of America,” as did Black activists who traced its roots to racism in America, “but also from empathy and identification with the Vietnamese.”11

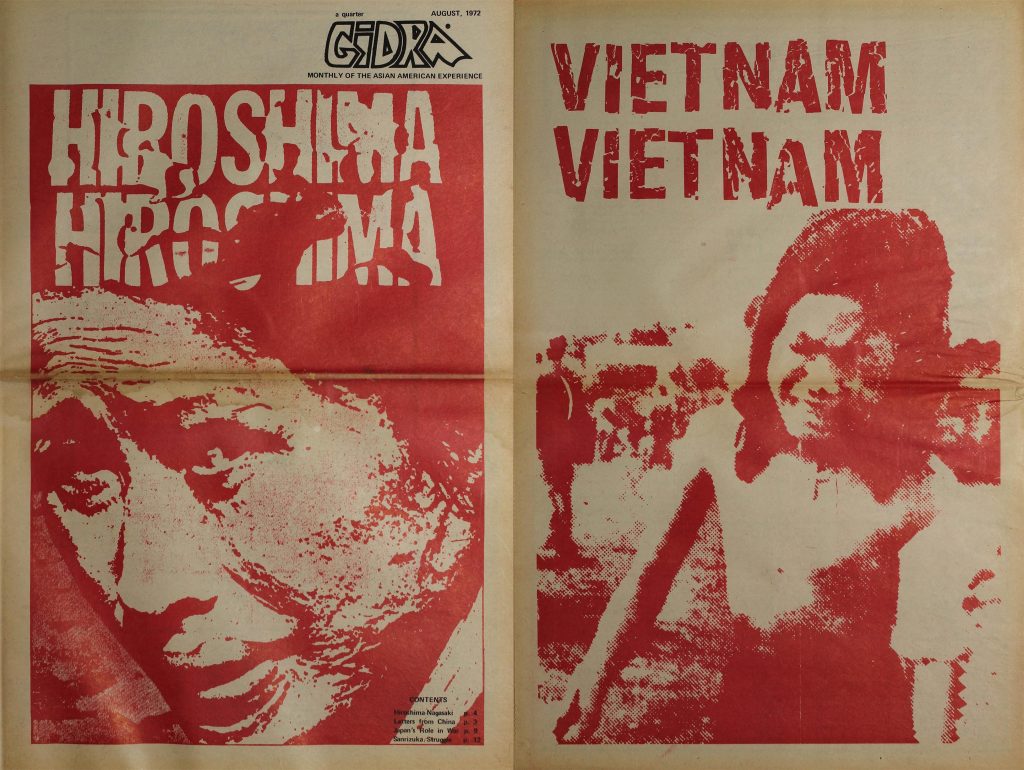

The racial slur “gook,” initially used against Filipino “natives” during the Philippine-American War before reappearing as a general anti-Asian epithet during the Korean War, made no distinctions between Asians in Vietnam and Asians in America.12 Asian Americans knew, intimately and immediately, the danger of “gookism,” having been on the receiving end of more than a century of anti-Asian exclusion and violence in the United States. Chester Cheng, linking the Japanese American incarceration and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to the “race extermination” taking place in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, put it this way: “We are able to unleash the most terrifying, vicious and horrible weapons devised by man in this war, because yellow people are as expendable as the buffalo and the American Indian. We are gooks in the eyes of White Americans.”13

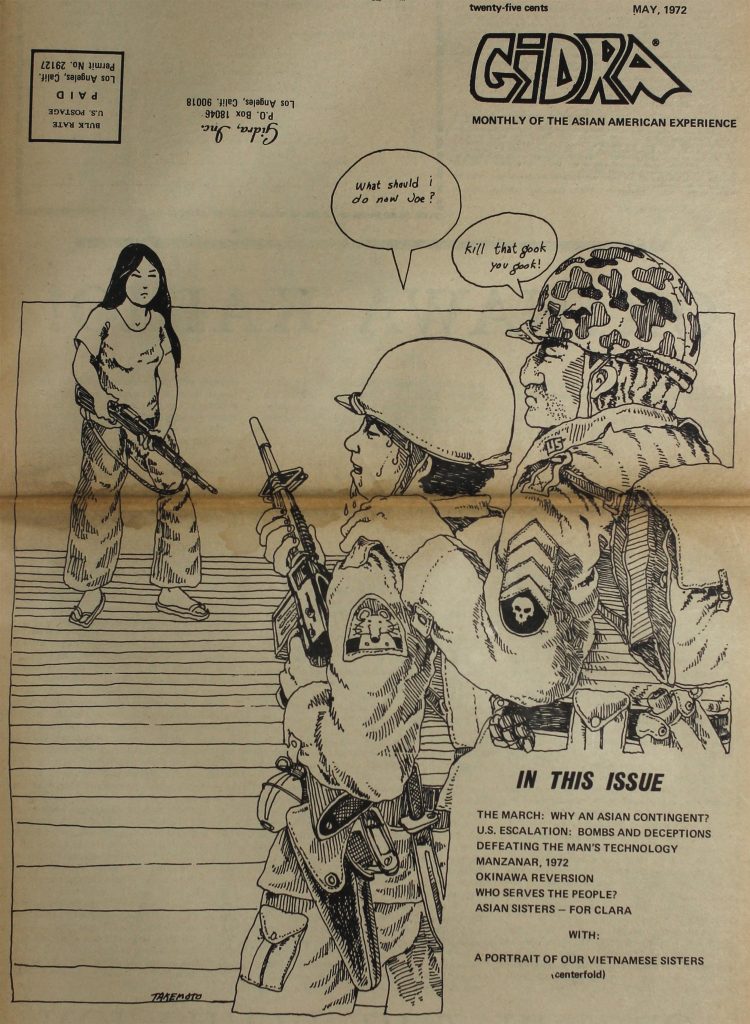

The U.S. military’s violently racist propaganda posed an imminent threat not only to the Vietnamese people soldiers encountered overseas but to the Asian Americans they met during and after their training. Soldiers “brainwashed” to see all Asians as subhuman enemy combatants brought the war home with them—and incidents of Asian Americans being assaulted by white GIs “back from fighting you communists in Vietnam” were not uncommon.14

Asian American veterans joined the anti-war movement after experiencing this military culture of fear and hatred firsthand.15 Former soldiers recalled racist abuse from their superior officers throughout basic training, from weathering a constant barrage of anti-Asian slurs to being used to show white recruits, “This is what the enemy looks like! We kill people who look like him!”16 Being conflated with the enemy became deadly “in country,” where they could be killed by their own troops or left behind by medevac teams who “thought you were VC.” And then there was the psychological toll of witnessing, and participating in, brutal acts of violence against people who looked like brothers, sisters, aunties, and grandfathers day in and day out—of being “a gook killing gooks.”17

Activists at home also struggled with their complicated status as both victims and perpetrators of U.S. imperialism. As Asians they felt a strong sense of kinship with the Vietnamese people, but as Americans they recognized that they “too share[d] in shedding Vietnam’s blood”—what Bruce Iwasaki aptly called “our national condition as victim and our international position as executioner.”18 Living “within the belly of the Monster” afforded Asian Americans certain privileges, however superficial and conditional, for ultimately it was not their families being maimed and displaced in Southeast Asia. If the good intentions and consciousness-building that had unified Asian America against the Vietnam War could not inspire concrete action, those theories and ideologies were merely “the regurgitations of an overly-rich diet.”19

‘Suzy Wong, Madam Butterfly and gook-ism must die’

The undeniably gendered nature of the Vietnam War added another layer of complexity to the Asian American anti-war movement.

The military machismo that turned GIs into “human killing machines” was doubly dangerous for the women who bore the brunt of violence in Southeast Asia—for they were devalued and dehumanized not just as “gooks” but as sexual objects. Many soldiers “believe[d] all Vietnamese women [were] whores,” and expected them to show a certain amount of “gratitude” to their American saviors.20 This casual misogyny fueled a sense of entitlement to women’s bodies: “slant-eyed chicks” had no right to refuse the men who were there to “protect” them. Consent was irrelevant.

An ex-soldier described the very real danger this mentality posed to Vietnamese women:

“You take a group of men and put them in a place where there are no round-eyed women. They are in an all-male environment. Let’s face it. Nature is nature. There are women available. Those women are of another culture, another color, another society. You don’t want a prostitute. You’ve got an M-16. What do you need to pay a lady for? You go down to the village and you take what you want.”21

Veterans’ accounts of their “tours” in Vietnam are full of stomach-churning examples of rape, torture, and murder of women and girls, while the language of the war—engagement, escalation, manpower, withdrawal, cherry, grunt, cocked, fucked—“conjur[es] up images of… a protracted and brutal act of sexual intercourse.”22 American brutality (like the horrific but by no means exceptional My Lai massacre, whose 504 victims were mostly women and children) was justified by the perceived alien-ness of the women, and men, of Vietnam. As Evelyn Yoshimura wrote for Gidra in 1971, “The image of a people with slanted eyes and slanted vaginas enhances the feeling that Asians are other than human, and therefore much easier to kill.”23

This gendered racism had consequences for Asian American women as well, from being “accosted by racist GIs who ‘know all about Asian women’ from their time spent with prostitutes in Vietnam and Hong Kong”24 to experiencing sexual assault and physical violence at the hands of former soldiers—like the brutal rape and murder of 17 year old Le My Hanh by ex-marine Louis Kahan.

Asian American women recognized racist attitudes about Asian women as cheap hookers, exotic geisha girls, and communist spies because those same stereotypes had been weaponized to ban their immigrant grandmothers and call for the forced sterilization of their mothers in WWII concentration camps. They identified with the women of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia not only as Asians fighting Western imperialism, but as women living at the intersections of racism and sexism. Asian Americans worked to amplify the voices of women who had witnessed the effects of U.S. military aggression in their home countries, meeting with Vietnamese political activists and touring the country to educate Americans about the war and the people impacted by it.25

Even as they encountered pushback from “Movement guys” unwilling to acknowledge their own role in perpetuating misogyny and white feminists who refused to accept their complicity in racism against women of color, Asian American women opened space for transnational coalitions with their Asian “sisters” and took on important leadership positions within the anti-war movement.

While Asian Americans were certainly not alone in protesting the Vietnam War, their shared racial background with the people of Southeast Asia made their motivations and perspectives unique within the anti-war movement. By connecting their experiences as “orientals” in America to the “gookism” deployed in Vietnam, they situated themselves as members of a global community of Asians engaged in a worldwide campaign to end racism, imperialism, economic exploitation, sexual violence, and other forms of oppression. Organizing against the war strengthened ties between Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, and Korean Americans redefining their racial and ethnic identities at a time when “Asian America”26 was still a new concept, and created opportunities for meaningful engagement with other “Third World” communities.

As a new generation grapples with the continuing legacy of American imperialism in Asia—threats of nuclear war with North Korea, the unrelenting growth of U.S. military infrastructure in Okinawa, mass deportations of Cambodian refugees to a country still littered with unexploded ordnance—the history of movements past offers important lessons for the future of Asian America.

—

By Densho Communications Coordinator Nina Wallace

[Header photo: Anti-war rally in San Francisco, 1969. Photo by Ray Okamura, courtesy of the Gidra Collection.]

Notes:

- Karen L. Ishizuka. Serve the People: Making Asian America in the Long Sixties (New York: Verso, 2016): 97.

- Bruce Iwasaki, “You May Be a Lover, But You Ain’t No Dancer.” Gidra, Vol. V, No 1 (January 1973): 16-17.

- Patsy Chan, “United Third World People Demand: End Your Racist War.” Gidra, Vol. III, No. 6 (June 1971): 5.

- Iwasaki.

- Daryl J. Maeda. Chains of Babylon: The Rise of Asian America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009): 126.

- William Wei. The Asian American Movement (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993): 40.

- Steve Louie, interview with Daryl J. Maeda, 1997. Quoted in Chains of Babylon, 124.

- Wilma Chen, “Toronto Women’s Conference.” Gidra, Vol. III, No. 5 (May 1971): 13.

- Maeda 124-25.

- “Moritorium.” Rodan, vol. 1, no. 10 (May 1971): 10.

- Ishizuka 110-11.

- Wei 38-39.

- Chester W. Cheng, “Hiroshima—Lest We Forget.” Gidra, Vol. II, No. 11 December 1970: 12

- Ishizuka 108.

- Mike Nakayama, “Winter Soldiers.” Gidra, Vol. III, No. 6 (July 1971): 12; Norman N. Nakamura, “The Nature of G.I. Racism” Gidra, Vol. II, No. 6 (June/July 1970): 4, 17.

- Maeda 104.

- Maeda 109.

- Iwasaki, “You May Be a Lover, But You Ain’t No Dancer.”

- Kazu Iijima, “In the Belly of the Monster…” Gidra, Vol. III, No. 4 (April 1971): 7.

- Nakamura, “The Nature of G.I. Racism.”

- Interview in Nam: The Vietnam War in the Words of the Men and Women Who Fought There by Mark Baker (New York: Quill, 1982): 206.

- Jacqueline E. Lawson, “She’s a pretty woman… for a gook: The Misogyny of the Vietnam War.” The Journal of American Culture, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Fall 1989): 58-59.

- Evelyn Yoshimura, “G.I.’s and Asian Women.” Gidra, Vol. III, No. 1 (January 1971): 4, 15.

- Wilma Chen, “Movement Contradiction.” Gidra, Vol. III, No. 1 (January 1971): 8.

- Patrell, “Glad They’re Back.” Gidra, Vol. II, No. 9 (October 1970): 4; Pat Sumi, “Laos: A Nation in Struggle.” Gidra, Vol. III, No. 3 (March 1971): 10-14; Nguyen Thi Dinh, “Twenty Years in the Revolution.” Gidra, Vol. III, No. 5 (May 1971): 10; Wilma Chen, “Toronto Women’s Conference”; Maeda 6-8.

- The “Asian America” of the 1970s was largely East Asian and heavily weighted toward Japanese and Chinese Americans. Consequently, South Asians, Southeast Asians, Pacific Islanders, and other communities now included under the broader (though still somewhat contentious) Asian American & Pacific Islander label are conspicuously absent from this chapter of Asian American history.