June 30, 2022

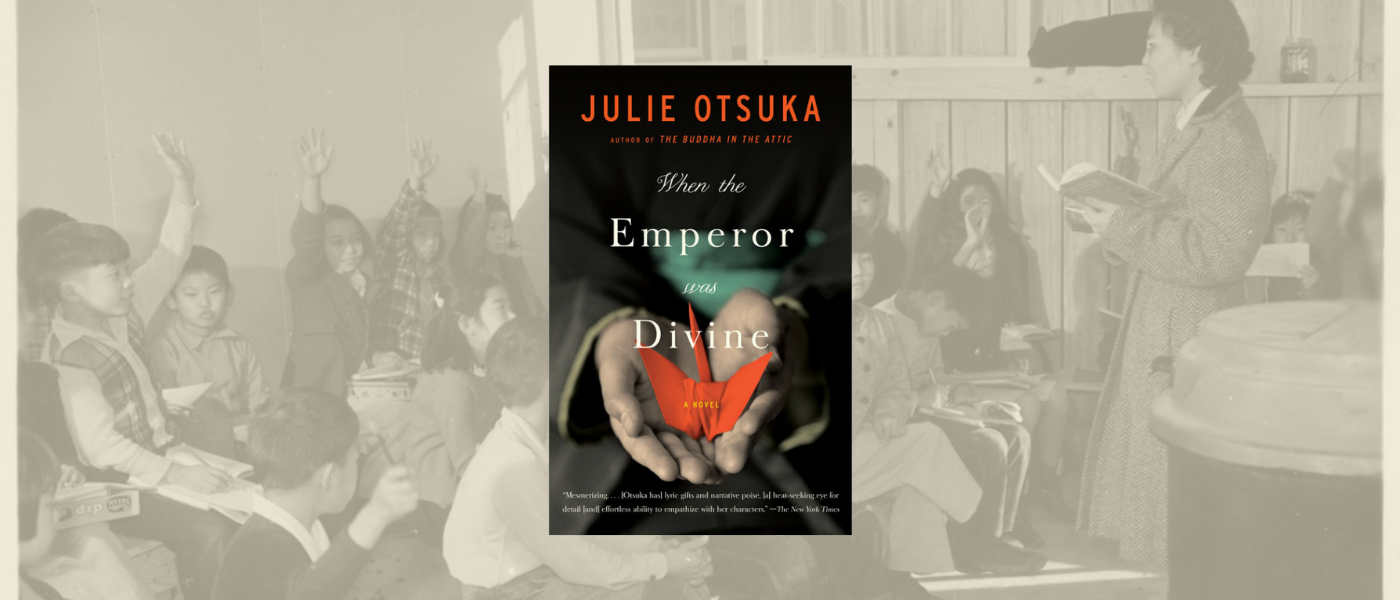

Julie Otsuka’s novel, When the Emperor Was Divine, has received numerous distinctions: an Alex Award from the American Library Association; a Literature Award from the Asian/Pacific American Librarians Association, and a prestigious Phoenix Award. The book — which is loosely based on Otsuka’s mother’s WWII experience — received overwhelmingly positive reviews when it was published in 2002, and was embraced by educators who found its content to be exceptionally relevant in the surge of Islamophobia that followed 9/11.

But now When the Emperor Was Divine has gained a distinction it didn’t deserve. It has been added to the growing list of books banned as part of the conservative backlash against Critical Race Theory.

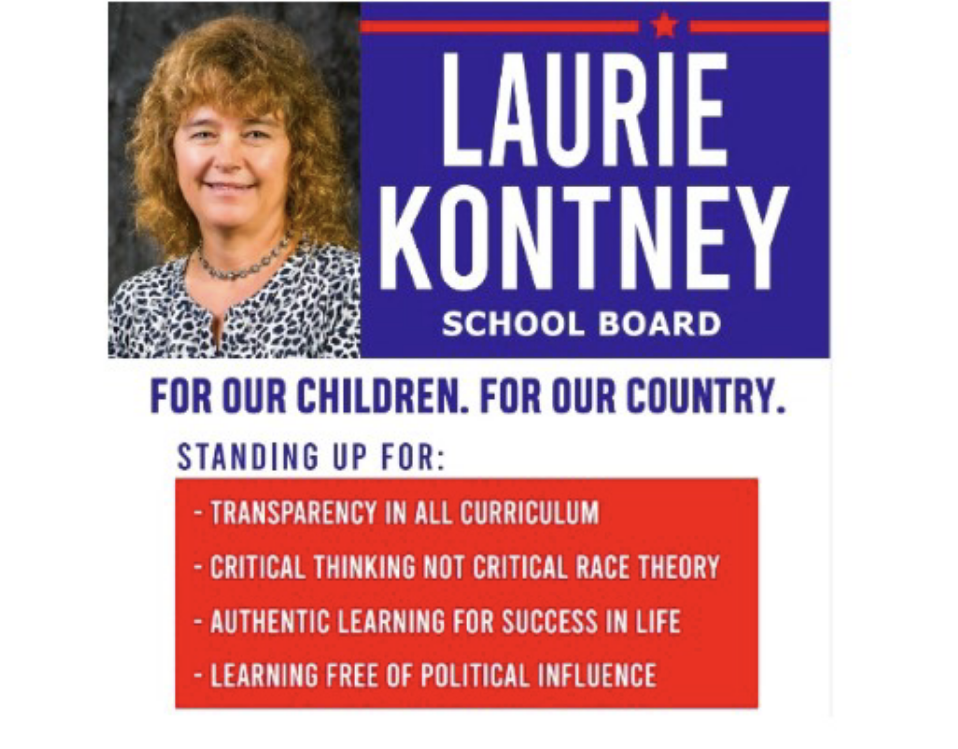

The ban stems from a request submitted this year by teachers in Wisconsin’s Muskego-Norway School District, who wanted to include the book in their 10th grade AP English class. Earlier this month, the district’s school board formally denied their request. The board offered little justification, other than to suggest that the inclusion of Otsuka’s book could create a problem with “balance,” since the curriculum already includes a 10-page excerpt from the memoir Farewell to Manzanar.

According to notes taken at the June 13 school board meeting and shared with The Wisconsin Examiner, board president Chris Buckmaster said that the sort of “balanced perspective” he had in mind could be found in a book like The Rape of Nanking, which details violence the Japanese imperial army enacted upon China. Yikes. This logic creates a false equivalency between the actions of a foreign army and the US government’s decision to incarcerate its own people. And in doing so it resuscitates the racist “enemy within” paranoia that led to this mass violation of Japanese American civil liberties in the first place.

Let’s be clear. There is no “other side” of the story when it comes to Japanese American incarceration. The US government unjustly incarcerated more than 125,000 of its own people without due process, an act that has been widely recognized as an egregious betrayal of constitutional rights. Unlike many of our country’s other historical wrongs, a formal apology and reparations were signed into federal law (after years of advocacy work by Japanese American activists). A congressional commission acknowledged the incarceration as a result of “racial prejudice, wartime hysteria and a lack of political leadership.” There is no need for a “balanced” perspective on this — and it is not up for debate.

The board’s decision to reject the book is an object lesson in white fragility. The Bulwark reports that Muskego’s population is 96.6% white, with a mere half a percent being of Asian descent. And as the entire backlash against Critical Race Theory has shown us, white supremacists are currently capitalizing upon a particular brand of discomfort around acknowledging our own history. This is just the latest iteration of a growing wave of ignorance and bigotry. We need to do all we can to stop it in its tracks because if we can’t learn about our past, we will never learn from it.

In a petition appealing the school board’s decision, residents of Muskego laid out a compelling counterargument:

“As residents of the world and heirs of its history, we must be given the opportunity to reflect on the past and point out the pain and suffering caused in the past. This reflection is meant to prepare ourselves to create a stronger country and world by rejecting outright the mistakes of the past. The reactions of the board to the proposal of this book have revealed the disgusting intention to foster ignorance and maintain the status quo within the district’s students and, by extension, the residents of Muskego. We believe that this book should be accepted for the classroom based solely on its academic value, and we are infuriated that it has been met with an ideology that forcefully shuts down any mention of historically disenfranchised people.”

In response to the controversy and the community’s response, author Julie Otsuka told Densho:

“I’m deeply disappointed by the school board’s decision, but also heartened by all the parents and students in Muskego who came out in opposition to the ban. To see a community rally around a book because they believe the truth must be told — that gives me hope. Especially now, when, with each passing day, more and more survivors of the camps are leaving us behind. Given the level of hatred that Asian Americans are experiencing in this current moment, it is more important than ever that students learn about our country’s racist past, and that the legacy of the Japanese American incarceration not be forgotten.”

The Japanese American Citizens League has also weighed in on the matter in a letter urging the school board to reconsider its decision, as did Jordan Pavlin, Otsuka’s editor and the current editor-in-chief at Alfred A. Knopf. Aura Sunada Newlin, Interim Executive Director of the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation has invited the school board to visit the site of the former Heart Mountain concentration camp so they can “experience the power of place and engage in dialogue about what happened here, how it happened, and why.”

The Muskego-Norway school board has yet to respond publicly to the backlash and has given no indication that they plan to rescind their decision. As elected officials charged with overseeing education in their district, it’s critical that they take this as an opportunity for learning and accountability. I’ll just leave their contact information here in case you’d like to join Densho in letting them know that it’s not too late to do the right thing.

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications and Public Engagement Director