October 27, 2016

Following a blueprint laid out by the Depression-era Mexican Repatriation, Japanese Americans were subjected to deportation during WWII as a punitive measure for their supposed disloyalty. This practice has been making a quiet comeback, with nearly three times as many immigrants deported since 1996 as in the rest of U.S. history combined.

Last month marked the twentieth anniversary of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA). Signed into law during the “tough on crime” Clinton years, the bill was rooted in a tired—and, unfortunately, not yet dead—mythology of dangerous white-woman-raping criminals and indigent anchor-baby-dropping migrants rushing the border. The unprecedented levels of immigrant detention and expedited deportations we see today are largely the result of this act.

IIRIRA applies to any non-citizen, including legal permanent residents, and lowers the bar for deportable offenses to minor, nonviolent crimes like drug possession or shoplifting. It can be applied retroactively, years after an individual has completed a prison sentence for their crime. Provisions for mandatory detention and fast-track deportation strip immigrants—even refugees applying for asylum—of their right to a court hearing. In cases that do make it to court, judges are prohibited from considering family ties, mental illness, abuse, fear of persecution, or any other mitigating factors during sentencing.

This story of immigrants being exiled to countries they left behind decades ago should set off alarms for anyone familiar with the “repatriation” of American and Peruvian Japanese during World War II. But these wartime deportations were not the first time the government attempted to remove an inconvenient immigrant population by force.

Having gained ample experience with forced migrations during the so-called Indian Removal period of the mid-19th century, local and federal governments initiated a massive deportation program aimed at Mexican Americans in the 1930s. Over 82,000 immigrants charged with illegal entry or other crimes were subject to involuntary repatriation—but the much larger number of permanent residents and children with U.S. citizenship could not, from a legal standpoint, be forced to leave. Instead, political leaders adopted policies designed to leave legal residents with no other option but returning to Mexico. Although they had chosen to leave under pressure, neither were they forced at gunpoint. This technicality allowed immigration officials to classify legal residents ineligible for formal deportation as “voluntary repatriates.”

To encourage self-deportation, municipalities across the country cut off aid to Mexican American families at the height of the Depression. New laws prohibited government contractors from hiring non-citizens and many private companies followed suit, refusing to hire even U.S. citizens of Mexican descent. Heavily publicized and often violent raids targeted union leaders and striking farm workers in order to quell protests. Citizens and permanent residents were arrested without warrants, denied a court hearing to prove their legal status, and summarily deported. (These disappearances also served as an effective fear tactic to scare families into leaving on their own.) Los Angeles County, whose efforts were especially tenacious, recruited Spanish-speakers to conduct door-to-door repatriation campaigns in Chicano neighborhoods, presenting residents with a list of reasons they were no longer welcome in the United States and a train ticket “back home.”

All told, at least one million Mexican Americans were deported south of the border—about 60% of them U.S. citizens. The transition was not easy. The Depression had only slowed Mexico’s recovery from the 1910 Revolution. Jobs were scarce and often denied to repatriados seen as having abandoned the country when times were tough only to return as a burden. Families who had no place to go once they arrived in Mexico lived in homeless encampments outside train stations.

These deportations peaked in 1931, but continued until the U.S. entered World War II and realized a cheap, exploitable labor force was needed to keep the economy and the war moving. Cue the Bracero Program. As Japanese Americans coped with the start of their own forced migration, many repatriados began to return home to the U.S.

Like the Depression-era deportations of Mexican immigrants and their families, repatriation during WWII was, on paper, a mostly voluntary program. Thousands of Issei families had already been pushed out of the country by anti-Japanese laws and agitation in the 1920s-30s, but repatriation took on new meaning in answer to the question of Japanese American loyalty in camp. The loyalty questionnaire of 1943 had given incarcerated Japanese Americans an (unintended) outlet to voice their malcontent, and almost a fifth of the responses came back negative or hedged with criticism.

The WRA soon after began to remove “disloyal” inmates from the general population and stuff them into the newly rebranded Tule Lake Segregation Center. In 1944, Congress passed a law enabling Americans to easily renounce their U.S. citizenship, and many Nisei showed their anger and disenchantment by doing just that. As conditions in Tule Lake deteriorated, applications for repatriation to Japan increased, reaching almost 20,000 by 1944.

In the meantime, the State Department was busy with its own repatriation program, negotiating the safe return of Americans stranded in Japan through prisoner exchanges. However, the U.S. found itself with a major disadvantage: although thousands of Japanese Americans had applied for repatriation, only a fraction had actually been requested for exchange by Japan. To increase their bargaining power, the U.S. turned to its southern neighbors, seizing over 2,200 Nikkei from Peru and several other Latin American countries in the name of “hemispheric security.” Issei men were removed first, brought to the U.S. and then arrested for attempting to enter the country illegally. Their wives and children were later coerced into “voluntary” internment in order to reunite the families.

Over 700 of these Japanese Latin Americans brought to the U.S. were used as hostages in exchanges with the Japanese government. While much smaller in number than their Mexican American counterparts, these repatriates also faced a harsh homecoming. Many of the Nisei had never set foot in Japan and spoke only Spanish. Their Issei parents recognized little in the impoverished, war-torn country and were often forced to impose upon relatives (already struggling themselves) for food and shelter.

Most of the Japanese Americans were able to avoid deportation to Japan—but not before an extended period of detention and a long legal battle. At the end of the war, 4,327 Tule Lake inmates were quietly denied release and slated for deportation. The majority had renounced their citizenship or applied for repatriation under duress, and 3,000 issued a new request to remain in the United States. After two years of legal wrangling, civil rights attorney Wayne Collins was able to quash their deportation orders—though the 1,327 individuals who had not enlisted Collins’ help still ended up in Japan.

U.S. repatriation efforts remained largely dormant until the 1990s. (“Operation Wetback,” which received praise from presidential candidate Donald Trump last year, again targeted Mexican Americans for deportation in the 1950s—but the Eisenhower administration made no attempt to cast it as a voluntary repatriation program. Ike apparently felt no need to hide behind a veneer of gov-speak.) IIRIRA opened the door to a renewal in forced repatriations.

Immigrants from Mexico and Central America make up the majority of the 5.4 million people deported under IIRIRA, but this repatriation revival has also had devastating effects on smaller, less visible communities. Since 1996, some 16,000 Cambodian, Vietnamese, and Lao refugees have been served deportation orders. Immigrants from the Caribbean are also extremely vulnerable, with 37,064 Dominicans and 17,314 Jamaicans deported between 2003 and 2013. Thousands more have been “returned” to Haiti, Cuba, Colombia, Nigeria, Somalia, Iraq, Pakistan, Myanmar, Micronesia, Tonga, Fiji, the Philippines, Peru, Sudan… This list is not comprehensive.

IIRIRA targets individuals we see as disposable: young Black and brown immigrants who have survived poverty, war, drug addiction, gang violence, police violence, sexual violence, only to be cast out of their adoptive home when they most needed help. The notion that empathy and second chances are privileges afforded only to those of us lucky enough to hold U.S. citizenship—that we would have made the right choice had we been there—pushes us to assign blame rather than admit there is a problem. It would be ridiculous to claim that Nisei renunciants somehow chose the deep betrayal that informed their decision to give up on their country. Yet we assume that immigrants and refugees facing deportation today chose to cross the border illegally, to sell drugs, to steal that garden hose from Wal-Mart independent of circumstances already decided for them. Survival is not a black-and-white choice between right and wrong. Clean hands are a luxury for people with easy choices.

To borrow the words of Lao refugee Xuliyah Potong, “If it is indeed true that it takes a whole village to raise one child, then what village is ultimately responsible for rehabilitating its wayward youth?” These men and women are a “product of American society,” not the distant lands of their ancestors. Their right to justice is our responsibility.

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Special Projects Coordinator

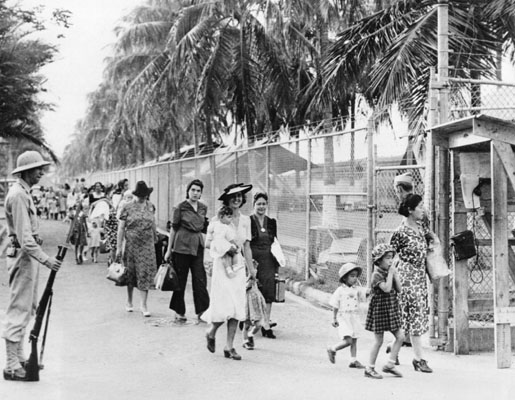

[Header photo: Original WRA caption: “Japanese repatriates embarking for Japan.” Although the WRA caption specifically refers to repatriates, many Japanese Americans who left were citizens of the United States and therefore, expatriates. November 24, 1945. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]