May 4, 2022

Famed marine biologist Eugenie Clark, or “Genie” as she was known to friends and family, was born in New York City on May 4, 1922. Her father, Charles Clark, died when she was just two years old, leaving her to be raised by her mother Yumiko. At around nine years old, her mother began dropping her off at the New York Aquarium while she’d work at a newspaper stand on Saturday mornings. This weekly routine—along with the central role of the sea in the Japanese culture passed down from her mother and stepfather—sparked an early interest in the ocean and the animals that call it home.

Young Eugenie soon convinced her mother to buy her several fish tanks, which housed an ever-expanding collection of various fish, toads, snakes, and even a small alligator. She knew early on that she wanted to pursue a career in oceanography, declaring to her family that she aspired to go “down in the bathysphere” like her childhood hero William Beebe. This declaration was met with some skepticism, she later recalled. “They said maybe you can take up typing and get to be a secretary to William Beebe or somebody like him. I said, ‘I don’t want to be anybody’s secretary!’”

Clark attended grade school in Queens, where she was the only Japanese student throughout her early education. As a Japanese American living on the East Coast, she was able to avoid incarceration during World War II and graduated from Hunter College with a bachelor’s degree in zoology in 1942. She married her first husband, Jideo Umaki, that same year and hoped to continue her studies at Columbia University. But after being told she would “have a bunch of kids and never do anything in science after we have invested our time and money in you,” she instead enrolled at New York University, earning a master’s degree in 1946 and a doctorate in 1950.

While in graduate school, Clark gained field experience at research facilities in California, Massachusetts, and the Bahamas. But she still faced hurdles as a young, multiracial woman in a male-dominated field. She and fellow grad student Betty Kamp were excluded from overnight research trips during their time at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in 1946. Much later in her career, she described feeling a push to “prove” that she belonged—and to make sure that male colleagues would not mistake professional interactions for something more. “We had to work extra hard, especially on field trips, to prove we could keep up with the males…. I somehow sensed that it was not wise to ever play up my role as a female or to encourage flirtations.”

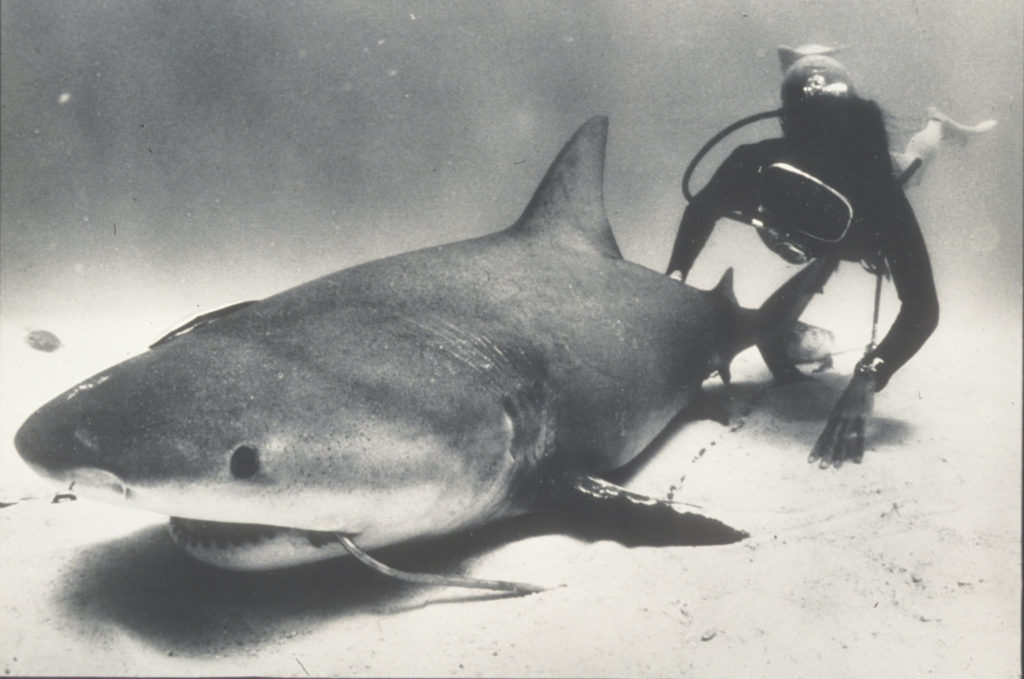

In 1949, she participated in a Naval program to study poisonous fish in Guam, Palau, the Marshall Islands, and throughout Micronesia—learning how to free dive and spearfish from Indigenous fishermen who she sought out for their knowledge of the local ecosystems. Upon finishing her doctoral degree the following year, she received a Fulbright scholarship to study fish populations in the Red Sea, collecting some 300 different species of fish. One of three new species she discovered was the Moses sole, whose natural shark repellent proved useful to later research on preventing harmful interactions between humans and sharks.

Her 1953 memoir, Lady with a Spear, documented this early part of her career. The book received wide acclaim and was reprinted in multiple languages, putting a spotlight on Clark as a rising star in the marine biology field. “I began to realize I had a talent for communicating about the natural world,” she said in a 1992 interview. “I came to see that it would be my life’s work.”

It also caught the attention of Anne and William Vanderbilt, who funded the creation of a marine laboratory in southwestern Florida under Clark’s leadership. The Cape Haze Marine Laboratory (now the Mote Marine Laboratory) began as a small operation, with just Clark and one assistant, local fisherman and seasoned shark catcher Beryl Chadwick. The new lab’s focus was on sharks—although their early efforts to capture and study them were admittedly crude.

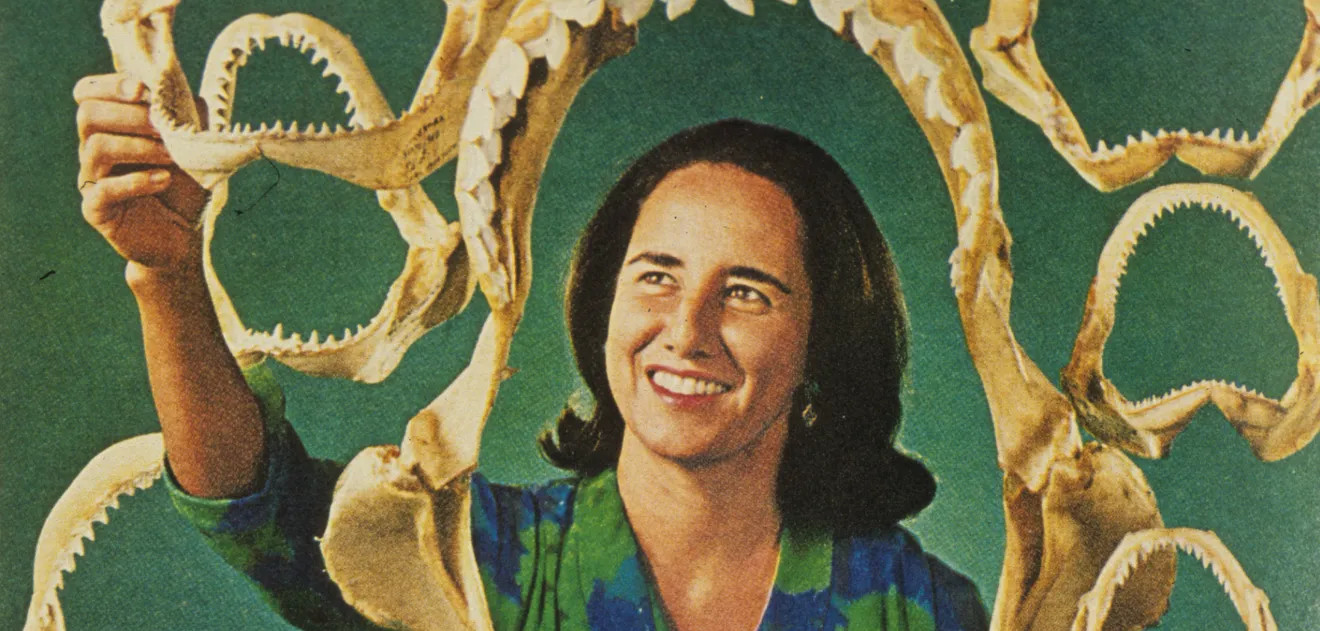

Clark’s work with sharks largely focused on dispelling myths popularized by the Jaws film series that painted them as mindless killing machines. She trained sharks to press targets to obtain food and to differentiate between distinct shapes and colors, demonstrating their intelligence and ability to learn, and gave educational talks and media interviews describing how these “gangsters of the deep,” as she called them, “had been given a bad rap.”

Clark’s career wasn’t the only part of her life to grow during this period. She’d married her second husband, a Greek orthopedist named Ilias Konstantinou, in 1950 and had her first child in 1952. Three more soon followed, keeping her busy as she raised a family, built up the marine lab, and continued to educate the public about the importance of preserving marine life.

The Shark Lady, as she came to be known, remained at the Cape Haze laboratory until 1967. Clark moved back to New York with her children during a brief third marriage, before taking a faculty position at the University of Maryland, College Park the following year. She married again soon after, but this partnership also ended in divorce a few years later.

Through these personal trials, Clark continued to push forward in her career, publishing a second memoir, The Lady and the Sharks, in 1969, and going on to lead hundreds of dives and research expeditions around the world, teach a generation of students, and win numerous awards for her contributions to zoology and conservation. She published a children’s book, The Desert Beneath the Sea, in 1992 and remained at the University of Maryland until 1999, though she continued to teach one class per semester for several years into her retirement.

Eugenie Clark completed her last dive in 2014, at age 92, and published its results in January 2015—just one month before her death on February 25, 2015. She left behind an impressive legacy, not just of scientific discovery and public education, but also as a trailblazer for other curious little girls who dream about exploring the wide world. As Brian Niiya wrote earlier this year, her remarkable life is a model for how we all might navigate the “shark filled waters of 2022” and beyond.

The US Postal Service just released a new stamp honoring Dr. Clark on what would have been her 100th birthday. Learn more and grab a few sheets to celebrate!

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Media & Outreach Manager