April 20, 2021

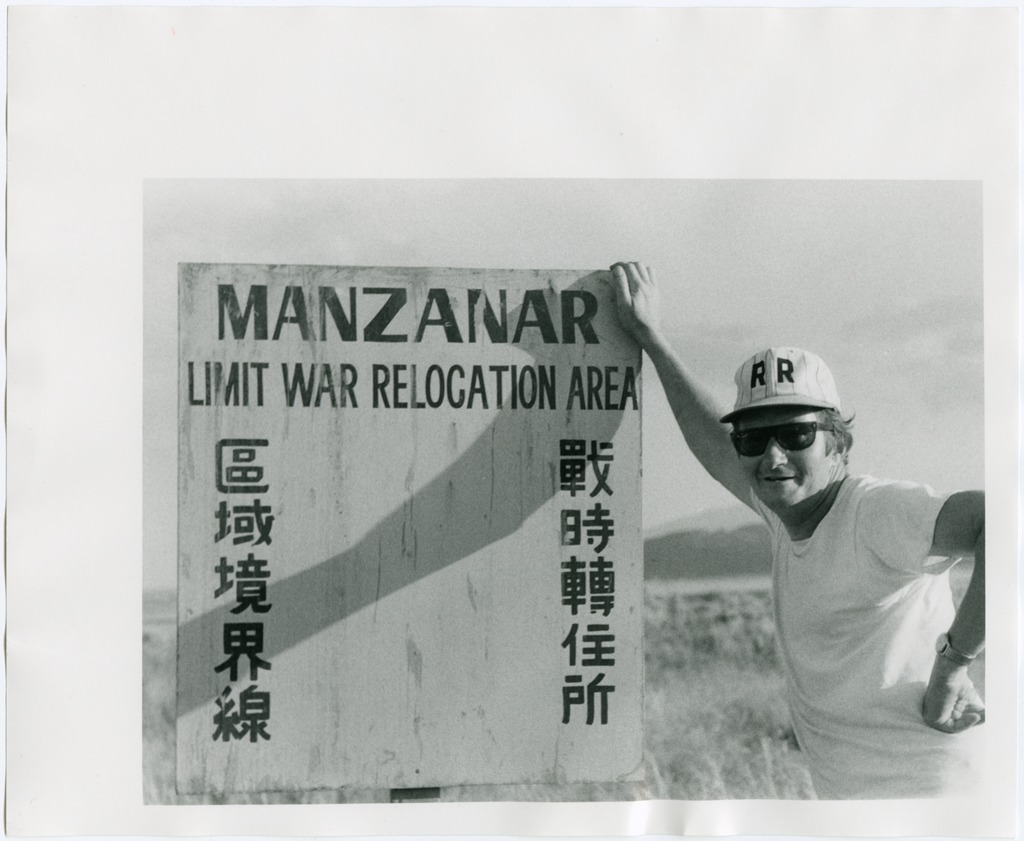

The first of America’s WWII concentration camps to be built, Manzanar was first at a lot of other things as well: the first to have an official historic marker, the site of the first public camp pilgrimage, the first to become a unit of the National Park Service, among other things. In addition to its extensive parks and gardens, and the iconic “Ireito” monument, Manzanar is also well known for the infamous “riot” (now more commonly referred to as an uprising) of December 1942, as the site of the Manzanar Children’s Village orphanage, and of an experimental guayule (a rubber substitute) project as well as one of three WRA camps to have a camouflage net factory.

And yet, there are many things even people well informed about the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans might not know. Here are ten such things:

Straight to Manzanar

The standard forced removal and incarceration storyline involves Japanese Americans being first sent to a short-term “assembly center” for a few weeks or months before being transferred again to a longer-term “relocation center” run by the War Relocation Authority (WRA). While this was the case for most incarcerated Japanese Americans, about one-quarter of them—a significant minority—did not go to an “assembly center” first. This was the case for the entire Manzanar population. Essentially everyone there went directly to Manzanar without passing through another camp first. This seems to not be commonly understood. In a good number of the many fictional accounts involving Manzanar (more on this below), inmates are described as coming to Manzanar from Santa Anita or another “assembly center” first. But with rare exceptions, this did not happen.

Manzanar opened in March of 1942 as the “Owens Valley Reception Center“—it later became the “Manzanar Reception Center” in mid-May—under the administration of the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) before being transferred to the WRA on June 1, 1942. So one could technically say that Manzanar inmates did go from a WCCA “reception center” to a WRA concentration camp. This is, however, a technicality, since the fundamental point—that Manzanites did not have to physically move a second time from WCCA camp to WRA camp—remains.

There were also around 10,000 Japanese Americans who went directly to Poston and around 3,000 each who went directly to Gila River and to Tule Lake without going first to assembly centers.

A large “volunteer” population

As the first of the concentration camps to be built, Manzanar became a bit of a laboratory at which the authorities tried some unique things. One of those was the notion of seeking “volunteers” from Los Angeles to go early to help set up the camp. The first eighty-four such “volunteers” arrived at Manzanar via bus on March 21, 1942, just a week after construction on the camp had begun. Two days later, 710 more arrived, some driving their own cars up in a caravan from Los Angeles, others coming by train or bus. Another 1,500 or so arrived over the next couple weeks.

Many of these “volunteers” came out of a sense of idealism. In a 1944 interview, GK reported that “there were many idealists among us who had visions of making it [Manzanar] the ideal community.” GA similarly recalled that his father brought the whole family, with “an idea that Eutopia (sic) could be created so that the war could pass them by.” Both were immediately disappointed upon arrival, with GA recalling that “[f]rom the first moment I stepped within that center, I knew that my dreams for a Utopia there were false illusions. I was bitterly disappointed and I really felt what the true meaning of evacuation was for the first time.”

The large number of such “volunteers”—whom some later inmates viewed as collaborators—may have contributed to the unstable mixture of inmates that led to later unrest at the camp.

While authorities continued to seek out cooperative Nikkei to be part of “advance crews” to help set up both WCCA and WRA run camps later on, the numbers were much smaller—typically a few dozen rather than hundreds or thousands—and those who “volunteered” were under fewer illusions as to what they volunteering for.

Wage disputes and broken promises

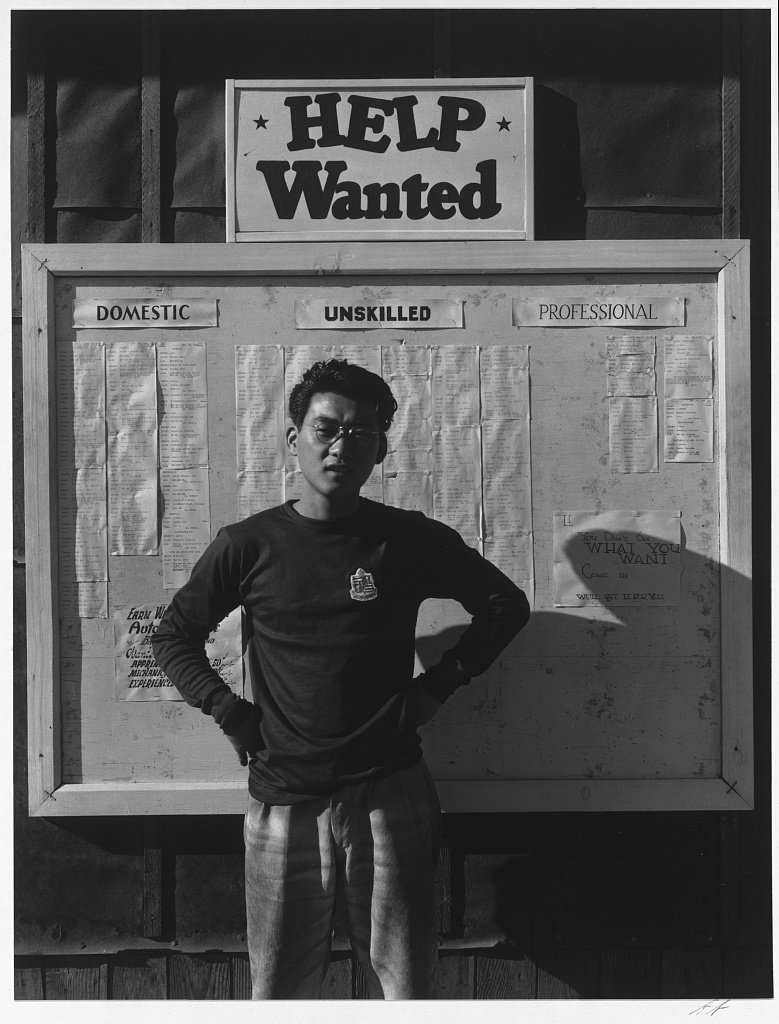

Another by-product of the haphazard early administration of Manzanar were misunderstandings about wages that would be paid to inmate workers. As at other camps, inmates were expected to perform many of the day-to-day tasks required to keep the camp running, something they would be paid for. But despite Manzanar opening in March, WCCA wage policy was not determined until May, and workers in the meantime didn’t have a clear idea of what the wage scale would be. Many of the “volunteers” had come believing that they would be paid prevailing outside wages for their work in helping to build Manzanar. Clayton Triggs, the camp manager in the WCCA period, reinforced this belief in early statements to inmate workers. So when the WCCA announced its paltry $8/$12/$16 per month wage scale (for “unskilled,” “skilled,” and “professional and technical” workers, respectively), far less than prevailing wages, widespread dissatisfaction spread. To make matters worse, paychecks were delayed for months, with payment for work done in March not issued until the end of June. The “broken promises” regarding wages were another factor in the unrest at Manzanar later in 1942.

Other than Santa Anita—which had some similar wage issues—the other “assembly centers” didn’t open until the end of April and thus didn’t have the same problems with wages as Manzanar. (Though the wages were still very low, inmates at the other camps largely knew what they would be paid from the outset.)

A mostly LA population — with a few noteworthy exceptions

Manzanar had one of the more homogeneous and urban camp populations, with some 88% of the original inmates coming from Los Angeles County and 72% from the City of Los Angeles. But among all the Angelenos, there were three distinct geographical groupings from rural areas outside of Southern California.

The most distinctive was probably the group from Bainbridge Island, Washington, a strawberry growing area just west of Seattle. Because of their supposed proximity to navy installations, islanders were subjected to the very first Civilian Exclusion Order issued on March 24, 1942. Since Manzanar was the only camp ready for occupancy at that time, the 227 islanders were sent there and were among the first to arrive at Manzanar, most of them ending up in Block 3. They remained a distinct group at Manzanar. Islander Sadayoshi Omoto recalled that they were “fish out of water because they didn’t really mix with the California population.”

The islanders pushed to be allowed to transfer to Minidoka, where most other people from the Seattle area were held, and when they were granted that opportunity, most decided to move. On February 24, 1943, 181 islanders left by train for Minidoka. Somewhat ironically, they remained a fairly distinct population at Minidoka as well, since they were a close-knit and largely rural population on the one hand, but were also seen as having brought “California customs along” on the other.

The other large non-Los Angeles groupings were from Florin and French Camp, farming communities outside of Sacramento and Stockton respectively. One of the communities split up by the incarceration, other Florin groups ended up at Tule Lake and Rowher. Many of the approximately 370 from Florin sent to Manzanar ended up in Block 30. About 178 from French Camp ended up in Block 27.

Late Tule Lake segregation

For various reasons, Manzanar inmates gave negative answers to the key questions on the loyalty questionnaire at a very high rate and subsequently ended up sending 2,165 inmates to Tule Lake, the largest number from any of the WRA camps. But while the segregation of “disloyal” inmates from the other camps mostly took place in September and October of 1943, the vast majority of those sent from Manzanar had to wait an additional four months for new barracks to be completed before they were sent to Tule Lake between February 21 and March 2, 1944. (A group of 290—about 13% of the total—did go to Tule Lake as part of the larger migration in October 1943.)

Limited Transfers from other camps

While most of the other WRA camps received some number of “loyal” inmates from Tule Lake as part of the segregation process, Manzanar was one of the three camps (along with Poston and Rohwer) that did not receive any inmates from Tule Lake. When Jerome closed in June of 1944, none of the Jerome inmates were sent to Manzanar either. As a result, Manzanar’s population dropped significantly after segregation, since very few inmates entered Manzanar after the end of May 1942.

Women administrative staffers

Manzanar was notable for having three high level female administrators, something not found at any other WRA camp.

Lucy W. Adams was the assistant director in charge of community management, one of three assistant directors installed under Camp Director Ralph Merritt after the riot/uprising. Her purview included health, education, community enterprises, welfare, and community activities (i.e. recreation). Adams was from Los Angeles and had a background in education and had also worked for the Office of Indian Affairs. She remained in her position until October 1944 when she left to take a position with the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, one of several Manzanar staffers to end up there.

Genevieve W. Carter was the superintendent of education and was one of the longest serving administrators, having been hired on June 15, 1942 and remaining in her position until the end of the education program in June 1945. Carter had an Ed.D. from the University of California and was working there as a staff member in the sociology department prior to coming to Manzanar. She had also worked as a social worker, teacher, and probation officer.

Margaret D’Ille was the head of the Community Welfare Section for nearly the entire life of Manzanar. Another University of California graduate, D’Ille had had a long career with the YWCA prior to the war, including a stint in Japan during which she learned to speak Japanese fluently. An old friend of Merritt’s, D’Ille was nearly sixty-three years old (and widowed) when she arrived at Manzanar in July 1942.

The only other women at any of the other camps to hold similar positions were Nell Findley, who was the chief of community services (later community management) at Poston from its opening to June 1943, and two social welfare heads (akin to D’ille’s position), Virgil Payne at Heart Mountain and Dorothy Montgomery at Tule Lake.

The Visual Education Museum

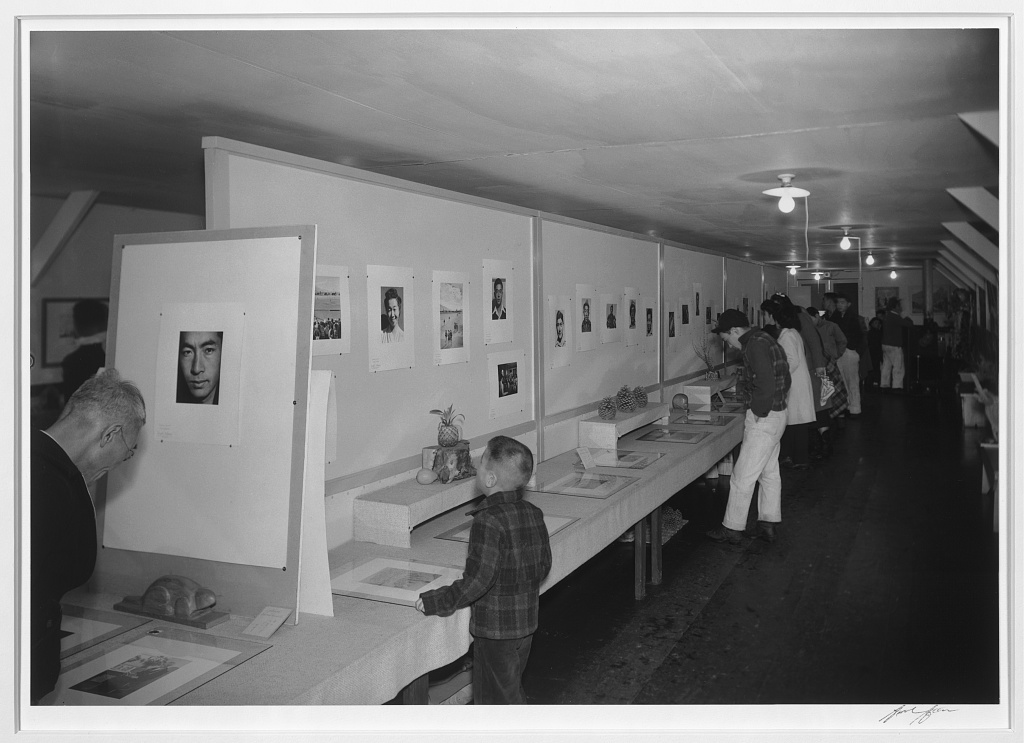

Another unusual feature of Manzanar was the Visual Education Museum, which was opened in the Block 8 recreation hall in December 1942. Museum director Kiyotsugu “Bill” Tsuchiya had an unusual background. A young Issei, Tsuchiya had settled in Chicago, where he attended art school and met eccentric millionaire George Harding, Jr. Harding had a mansion in Hyde Park that he filled with a collection of art and medieval arts and armor, and ended up hiring Tsuchiya to be its curator. Tsuchiya served in that capacity from 1924 to 1940, organizing, caring for, and displaying the objects, while living in the mansion. After Harding’s death in 1940, Tsuchiya moved to LA with his Nisei wife Chie, where he ran a nursery in Culver City, before he ended up at Manzanar.

Given his prior experience, Merritt asked Tsuchiya to organize the Visual Education Museum, which opened in the Block 8 recreation hall in December 1942. Featuring everything from craft displays to various fine arts, ikebana, photography, and many other objects, exhibits were changed twice a month and were drawing up to 4,000 people by mid-1943. Toyo Miyatake was among the museum staff that worked with Tsuchiya. Museum staff also kept a small zoo outside, featuring local fauna as well as a small park with picnic tables and a stone barbeque pit. The museum remained open until the end of May 1945.

More Industrial Enterprises than any other camp

Manzanar had an unusual number of industrial enterprises that also served as vocational training sites for the inmates. These ventures were likely another by-product of Manzanar being the first camp. Other camps had some of these types of enterprises, but none had this many.

A clothing factory opened in August 1942 that mostly produced work clothing—masks and arm protectors for the camouflage net factory, hospital uniforms, etc.—and children’s clothes. Some was distributed directly to workers, others were sold by the co-op, and some was even shipped to other WRA camps. The factory opened in the Block 2 ironing room, but quickly outgrew that space and came to have an average of sixty-five workers working in two warehouse buildings. Factory workers learned industrial sewing skills on industrial sewing machines sourced from the WPA that they could use on the outside. The factory produced an average of 4,000 garments per month during its peak. It closed in September 1944.

An alterations shop employed an average of seventeen and was primarily charged with reworking the surplus World War I clothing provided for the inmates into usable garments. A furniture factory produced pieces for use in the camp, while employing a crew of twenty-two. The shop also produced wooden toys for Christmas 1943 that were sold by the co-op. There was a typewriter repair shop and a sign making shop. A mattress factory produced eight hundred mattresses a week starting in January 1944 to replace the straw tic mattresses the inmates used. Various Japanese food enterprises—shoyu, bean sprouts, tofu, miso, tsukemono (Japanese style pickled vegetables)—produced familiar foods for use in the mess halls.

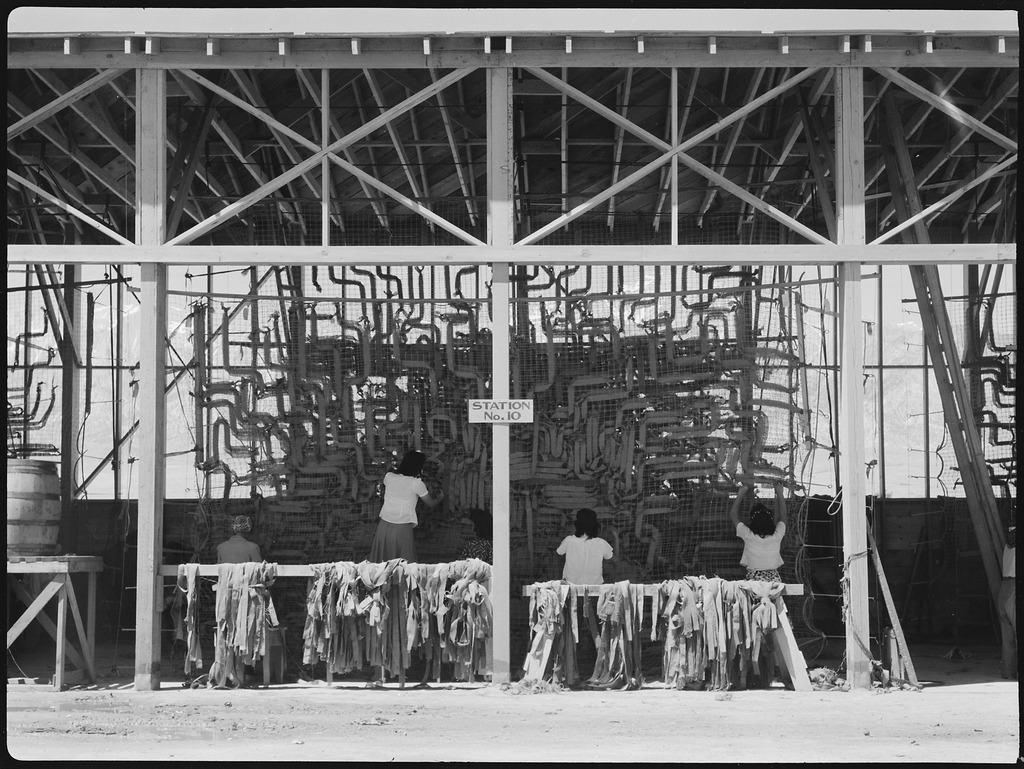

And, as noted above, Manzanar was one of three WRA camps to have a camouflage net factory.

Fictional representations

While I haven’t done any kind of systematic study of this, I think it is pretty clear that Manzanar is the best known of the ten WRA camps and also the one that is depicted most often in fictional accounts, whether novels, short stories, plays, or film/video. Much of the credit, I think, has to do with the enduring influence of Farewell to Manzanar, first as a memoir by Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston published in 1973, then as a nationally televised, made-for-TV movie first broadcast on NBC in 1976. I think this phenomenon also has to do with its relative proximity to Los Angeles, a large city that has a significant Japanese American community, and to the fact that the vast majority of its inmate population came from L.A.

Rather than listing all of the fictional works on Manzanar, I thought I’d note some of the more unusual or worthwhile ones that are less well known and that I’ve not written about before.

American Scrapbook (1969) by Jerome Charyn was one of the first published novels to be set in America’s concentration camps and follows a family at Manzanar and Tule Lake. It was largely panned by mainstream and Japanese American reviewers, deservedly in my opinion, for its unusual structure and crude and unrealistic portrayals of Japanese Americans. Japanese Canadian author Leslie Shimotakahara fictionalizes Manzanar as “Matanzas” for some reason in her novel After the Bloom (2017), which moves back and forth between the burgeoning redress movement in 1984 and the war years. Michael Holloway Perronne’s Gardens of Hope (2016) is likely the only novel set in camp that focuses on a same sex romance, centering on a young white man who never gets over his affair with a Nisei man who gets sent to Manzanar. And then there is Toyoko Yamasaki’s notorious Futatsu no sokoku (1983; published in English translation as Two Homelands in 2007), a best-selling novel in Japan by a popular author that was made into a widely viewed television series. In the context of the Redress Movement, Japanese Americans strongly objected to the portrayal of Nisei split loyalties in the book and TV series, and the JACL prevented its being shown in the continental U.S. (See more of my takes on a few of the many other novels set in Manzanar here.)

There are also numerous children’s books set in part in Manzanar, among them such high profile recent titles as Lois Sepahban’s Paper Wishes (2016), about the first months at Manzanar for a ten-year old girl from Bainbridge Island; Amy Gordon’s Painting the Rainbow (2014), a coming-of-age novel set in 1965 that turns on events that took place at Manzanar; and Kevin C. Pyle’s Take What You Can Carry (2012), a graphic novel that moves between the war years at Manzanar and 1970s Chicago. Eve Bunting’s So Far from the Sea (1998), with illustrations by Chris K. Soentpiet, is about a Japanese American family’s return to Manzanar in 1972 and is one of the best picture books for young children about camp.

Finally, there are Hollywood films. The first depiction of the American concentration camps in a Hollywood movie is in Hell to Eternity (1960), about real-life Mexican American war hero Guy Gabaldon (though his ethnicity is scrubbed from the film), who is taken in by a Japanese American family. Guy and his friends see Japanese Americans being forcibly removed from their homes, and he later visits his foster family at Manzanar. Perhaps the two highest profile Hollywood depictions of the incarceration are in Come See the Paradise (1990) and Snow Falling on Cedars (1999), the Japanese American characters in each having been incarcerated at Manzanar. Finally, there is the 1943 serial G-Men vs. The Black Dragon, which includes a Japanese American character—portrayed as a spy, of course—who had been at Manzanar. There are also a few independent shorts set in Manzanar as well as a great many documentaries.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

The information presented here has been excerpted from Densho’s new and improved Sites of Shame project, coming to a device near you later this year. Full citations will be included there, but feel free to post questions in the comments or email us at info@densho.org in the meantime!

[Header image: High school students walking between barracks in Manzanar during recess. Photo by Ansel Adams, courtesy of the Library of Congress.]