March 29, 2017

March 30, 2017 marks the 75th anniversary of the removal of Japanese Americans from Bainbridge Island, Washington. The community of almost 300 was the second in the country targeted for eviction—after Terminal Island, where residents were given a mere 48 hours to pack up and move further inland—and the first taken directly to a concentration camp. We offer a look back at this historic date with photos taken during the March 1942 removal.

Japanese Americans had lived on Bainbridge Island since the 1880s, establishing a small but thriving community near the Port Blakely Mill, where Japanese immigrants worked alongside a diverse crew of Native Americans and fellow immigrants from Hawai’i, the Philippines, Italy, Finland, Sweden, and China. It was a Japanese American family, the Moritanis, who introduced strawberry farming to the island in 1908, and by World War II most Nikkei islanders were engaged in some form of agricultural business.

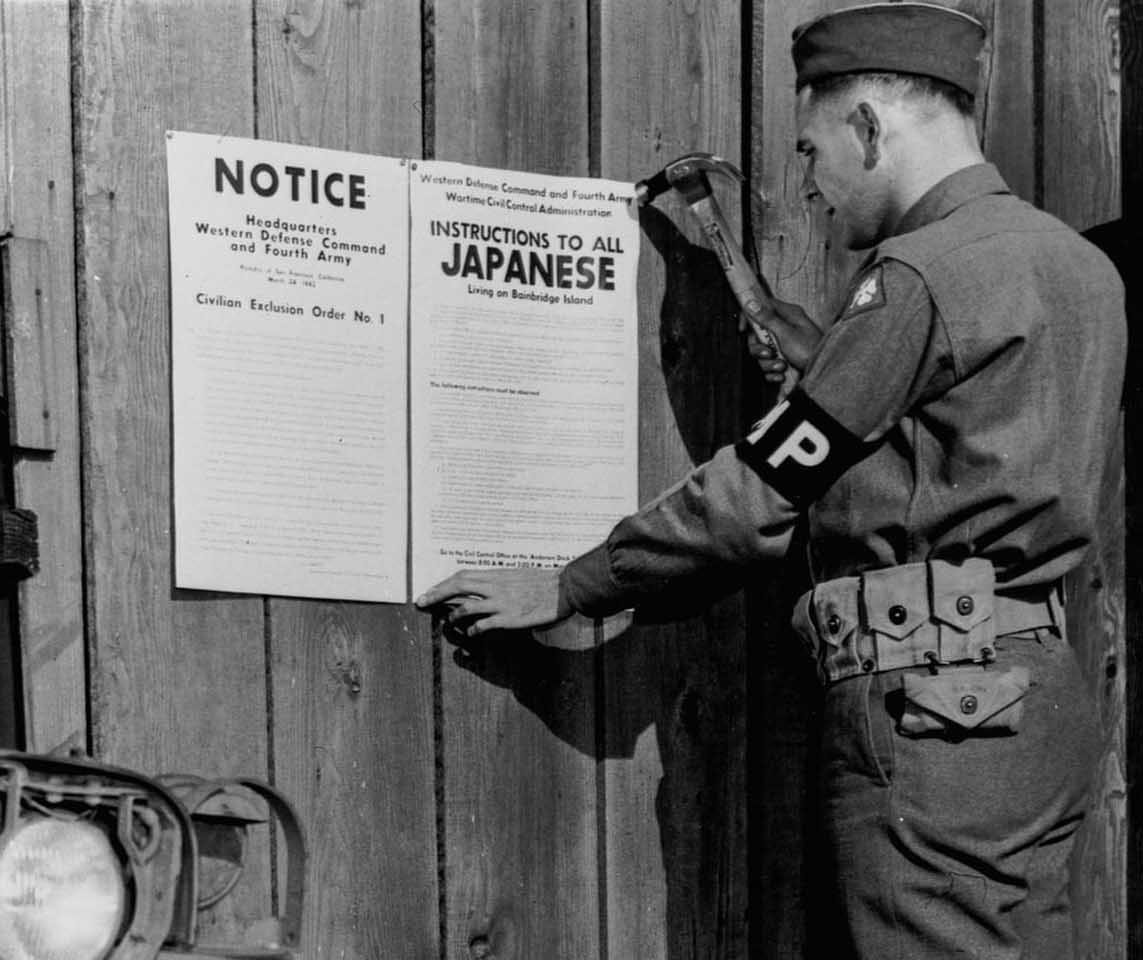

On March 24, 1942, a little over a month after Executive Order 9066, Western Defense Commander John DeWitt issued an exclusion order against the Japanese American residents of Bainbridge Island, citing the island’s close proximity to the Puget Sound Navy Yard. Those affected by the order had just six days to sell or lease their farms, store their property (or sell it for pennies on the dollar), find new homes for pets, and say their goodbyes. These photos show the exclusion orders being posted, on or about March 25, 1942.

The government was ill-prepared for this first removal and made the “evacuation” of Bainbridge Island especially difficult by providing Japanese Americans with confusing and conflicting information. Additionally, the support network of churches and other community organizations that eventually formed to help Japanese Americans pack and store belongings was not yet in place. Bainbridge Islanders had to prepare for their eviction largely on their own.

Local papers like The Seattle Times praised the “orderly evacuation” as “a credit to the efficiency of the army”—and, as the next photos clearly show, it was indeed a military operation.

All Japanese American residents of Bainbridge Island were required to report at the Eagledale ferry dock, where they would be transported across the Puget Sound to Seattle. Many families arrived wearing their best clothing, uncertain of where they were being taken and no doubt feeling pressure to make a good impression.

Bainbridge High School excused students so they could say goodbye to their Japanese American friends, and other Islanders came to see them off. The ferry Keholoken left Bainbridge Island at 11:20 am, carrying 227 exiled Japanese Americans. (Another fifty-two Nikkei residents had already left “voluntarily,” according to The Seattle Times.) Upon landing in Seattle, the passengers were immediately transferred to a train bound for Manzanar, then known as the Owens Valley Reception Center.

After a multi-day train ride, Bainbridge Island’s Japanese American community arrived in Manzanar. The camp was still under construction, and some Islanders joined the group of volunteers already working to complete the sewer system, barracks, and other crucial facilities. As additional exclusion orders were carried out across the West Coast, Manzanar began to fill with new arrivals—largely from the L.A. area. Tension between Bainbridge Islanders and the L.A. crowd, combined with Seattle’s Nikkei population being sent to faraway Minidoka, led many to request a transfer to join their friends and family in Idaho. The WRA eventually granted permission for the transfers, and 177 Islanders arrived in Minidoka on February 26, 1943, with five families opting to remain in Manzanar.

Today, the former Eagledale ferry dock is the site of the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial, an outdoor exhibit that honors the names of all 276 Japanese Americans exiled from the island by Executive Order 9066 and serves as a reminder of what happened on March 30, 1942.

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Communications Coordinator

[Header photo: Japanese American families walk down the Eagledale ferry dock to catch the special ferry to Seattle. Bainbridge Island, March 30, 1942. Courtesy of the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community.]