CAMPU: Episode 5 “Latrines” Transcript

Keep scrolling to read this episode’s transcript, or download a copy here.

VO: Hey, this is Hana. If you like what we’re doing, subscribe, share, leave us a review on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you’re listening to this. It really does help us out. Thanks so much.

VO: This is a story about the lavatory. That’s how Marian Asao Kurosu, an Issei woman, begins the tale.

MARIAN ASAO KUROSU: [in Japanese] This is a story about the lavatory. There was a huge hole below you. A big one. Then a two-by-four was placed between that side and this side. As you know, you lower your hips. [Laughs] It was like that at first when we entered the camp.

VO: The lack of privacy profoundly shaped the day to day experience of the camps. In the barracks, mess halls, classrooms, laundry rooms, latrines—everywhere, really.

ROKURO KURIHARA: We ate together. Showered together.

MASAKO MURAKAMI: No privacy at all.

VO: In the barracks at the assembly centers, the walls didn’t go all the way up to the ceiling. Sounds carried, to say the least.

GEORGE AZUMANO: Each family was assigned one room with partition room but no ceiling, so you can hear the neighbors talking

FRANK YAMASAKI: Somebody letting a fart on one end, you could hear all the way across.

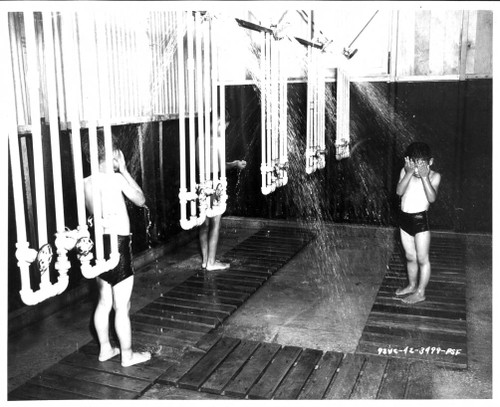

VO: The communal latrines and showers only amplified these problems.

AZUMANO: There were only I think two latrines in the whole area. Three thousand people were there… There were several showers in the room, but there’s only one shower room as I recall.

VO: In this episode, we’re going to talk about everything you never wanted to know about the latrines and … what goes on inside them. And it’s not all about poop, I promise.

Theme.

VO: From Densho, I’m Hana Maruyama and this is Campu.

End theme.

VO: Before we get started, I want to give you a heads up: this episode will contain discussions of sexual violence and murder.

VO: When incarcerees first arrived at the assembly centers, the lack of privacy was extremely jarring.

MIKA HIUGA: When we went to camp, we’re used to privacy.

CHORUS: Privacy.

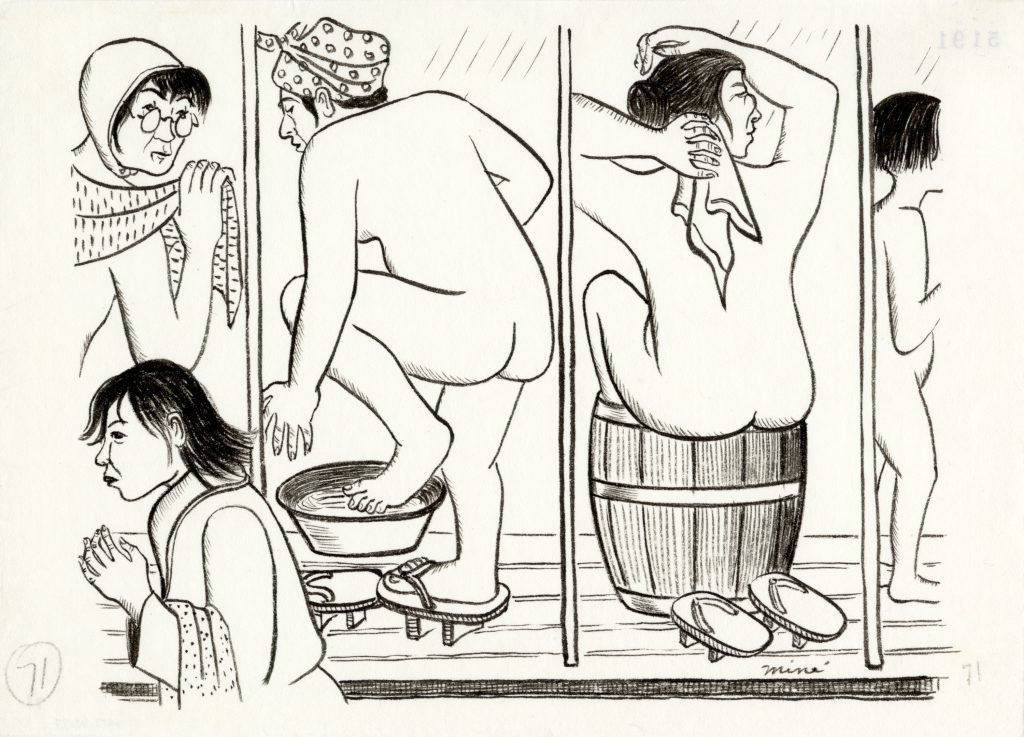

AKIKO KUROSE: We never even undressed in front of our sisters, you know.

HOPE OMACHI KAWASHIMA: I remember I hated to go to the bathroom because—

JIM KAJIWARA: going into those johns where—

SACHI KANESHIRO: the toilet side was just one wooden plank with holes in it.

ETSUKO ICHIKAWA OSAKI: You’re just sitting on these holes.

GEORGE AZUMANO: just placed in a row—

ISAO KIKUCHI: —maybe two feet apart, so if you’re going, you’re sittin’ there rubbin’ elbows.

CHERRY KINOSHITA: and then a gush of water every once in a while coming through to clear it.

BETTY FUJIMOTO KASHIWAGI: My mother kept saying “either wear a skirt or take a magazine.”

GEORGE ISERI: we call them eight passenger coupes.

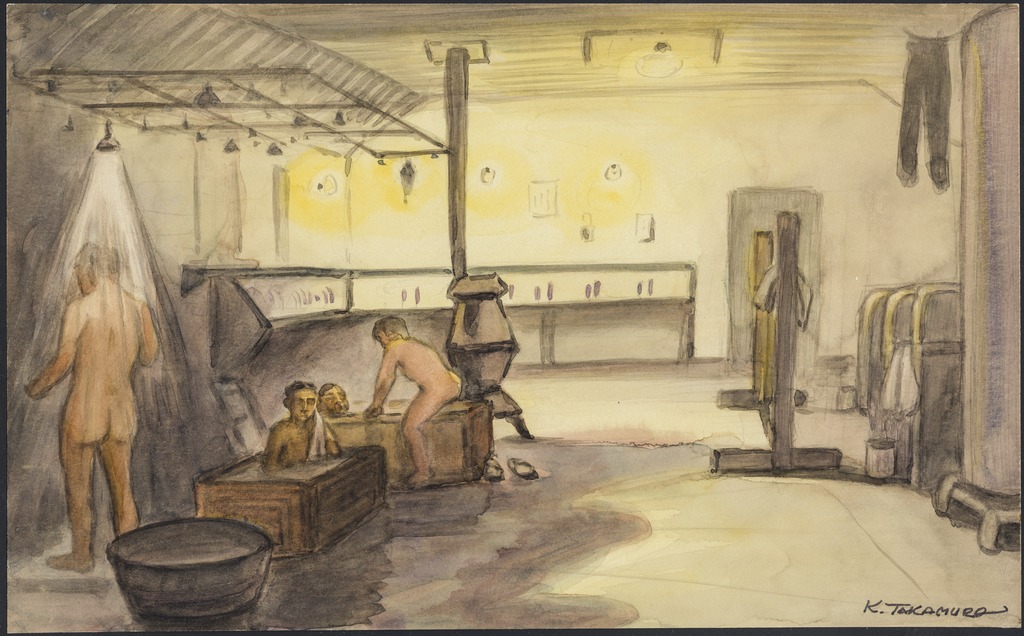

GEORGE AZUMANO: Same as the shower—

DOROTHY KUWAYE: there were no shower curtains—

CHORUS: No stalls. No partitions. No privacy.

TAYLOR TOMITA: —nothing, just all wide open.

HIROSHI KASHIWAGI: It was really bad.

HOPE OMACHI KAWASHIMA: it smelled terrible.

KASHIWAGI: There was just one partition. Women were on the other side of the partition and we were on this side.

LUCY KIRIHARA: People could be walking above on a little catwalk so you had to take a shower in your bathing suit.

MIKA HIUGA: At first, it was very hard for us and especially the Issei women—

GRACE WATANABE KIMURA: some of the older women who were very modest—

SUE KUNITOMI EMBREY: people like—

CHORUS: My mother.

MAS OKUI: She would go really late at night—

EMBREY: would stay up late hoping to take a shower when her neighbors weren’t around—

GRACE WATANABE KIMURA: —during the midnight hours so that nobody could see them.

KEIKO KAGEYAMA: I went when nobody else was taking a shower.

KANESHIRO: First thing in the morning before anybody got up. I mean it was still dark—

EMBREY: but they all stayed up late. They all wanted to take their shower in privacy.

KANESHIRO: And wouldn’t you know, there was a whole bunch of people already there thinking the same thing.

DOROTHY KUWAYE: I wasn’t used to all that public display.

AKIKO KUROSE: Taking a shower with multiple groups of people was very—

CHORUS: devastating.

JIM KAJIWARA: I felt like a criminal at that time—

HENRY SAKAMOTO: particularly if you were modest and shy—

DOROTHY H. SATO: That was very hard to accept—the invasion.

VO: And that wasn’t the worst of it.

LOUISE KASHINO: Once they gave us—

CHORUS: Vienna sausage.

KASHINO: —the kind in the cans. They gave it to us for several days in a row.

VO: Everybody ate the same food in the same mess halls. And used the same latrines. Maybe you see where we’re going with this.

FRANK KITAMOTO: First week there, everyone got—

ISAO KIKUCHI: everybody’s got—

LOUISE KASHINO: people got—

VICTOR IKEDA: —food poisoning.

KASHINO: —diarrhea.

KIKUCHI: —the runs, that was very common in camp.

TOSHIKAZU “TOSH” OKAMOTO: The refrigeration system wasn’t very good.

VO: With inadequate refrigeration in the middle of summer and untrained chefs suddenly tasked with preparing food for hundreds of people, food poisoning ran rampant in the assembly centers. Whole blocks of people—200 plus—could come down with food poisoning in a moment.

ISAO KIKUCHI: I was walking across the camp and I just jumped into every can I came by—

VO: Long lines would form outside the latrines, but when you’ve got the runs, waiting in line isn’t really an option.

KIKUCHI: You look up and you see this gal mopping the floor. By now we’re getting used to anything, since, she said, “Lift your feet.”

KIKUCHI: And guy’s standing there jumping up and down and he just can’t wait, so he just walked into the shower and turned it on. [Laughs] Nobody had any, anything to say ’cause we’re all in the same, got the runs.

KIKUCHI: That kept that camp half alive.

VO: It might sound funny, but remember this was the 1940s in a concentration camp.

FRANK KITAMOTO: This elderly Issei, first-generation woman came up to her and said, “they’re gonna poison us and we’re all gonna die. And we’ll never leave this place.”

VO: There were only two doctors in Fresno Assembly Center and the “hospital”—if it could even be called that—only had castor oil and rubbing alcohol for supplies. No antibiotics—which weren’t available to civilians anyways—or IV bags. Dr. Kikuo H. Taira had placed an order for additional supplies weeks ago but the administration told him that they needed six months to complete his order.

VO: The culprit on this particular occasion was a bad batch of macaroni salad. Dr. Taira later said, “that’s deadly stuff in the summer.”

VO: Finally, the social welfare chairman went into town on an emergency basis to buy IV kits. Dr. Taira later said in an oral history that people quote “were falling down here and there, and so they were brought to the hospital by the stretcher boys.” At one point, he “thought some were going to die.” Fortunately, none did.

VO: Fresno wasn’t the only assembly center to struggle with food poisoning. At Puyallup, a guard became increasingly alarmed when he saw crowds of people hurrying to the latrines one night.

VICTOR IKEDA: In the middle of the night you had the runs so you had people running to the latrine—

LOUISE KASHINO: everybody was rushing to the bathroom—

FRANK YAMASAKI: simultaneously they all went toward the toilet—

KASHINO: Sometimes you had to go two or three blocks to get to the bathroom.

IKEDA: and the guards got kind of frantic—

KASHINO: and I remember the guards on top of the grandstand turned the floodlights on—

YAMASAKI: he turned the light on—

KASHINO: and their guns down at us—

YAMASAKI: and the guard on the tower thought there was going to be a riot.

IKEDA: ‘cause everybody was heading for the latrine.

KASHINO: It wasn’t a stampede, but it was just everybody had a problem.

YAMASAKI: —and he swung around and… as you go up the ladder to this platform, there’s a hole there, and I understood he fell down. Fell through there. [Laughs]

VO: Some got used to the latrines.

MIKA HIUGA: Pretty soon, you just think, well, we’re all the same so let it all hang out. [Laughs] What else could we do if you have to go?

VO: Other incarcerees found ways to cope with the lack of privacy.

MIN TONAI: There was one enterprising girl who somehow found a large cardboard box, and when she had to go to the bathroom she would carry that, put it around her.

HIKOJI TAKEUCHI: We found cardboard, pick it up, and we store it in a certain part of the latrine, and when we get enough … made stalls for the women.

FRED ODA: Lot of the ladies, they got cardboard and they made their own partition.

LILY KAJIWARA: I think some enterprising person put up some partitions, but it was wide open.

HELEN TANIGAWA TSUCHIYA: When we had our period, you know, what are you going to do? So we told my brother, I said, “You have to help us. At least find something that we could put at the last stall and then we will watch.” So he looked around and he found a cardboard. And he put it up, every time anyone was like that we said, “Go in there. We will watch you.” And that really helped. That really helped. Otherwise it was just gruesome.

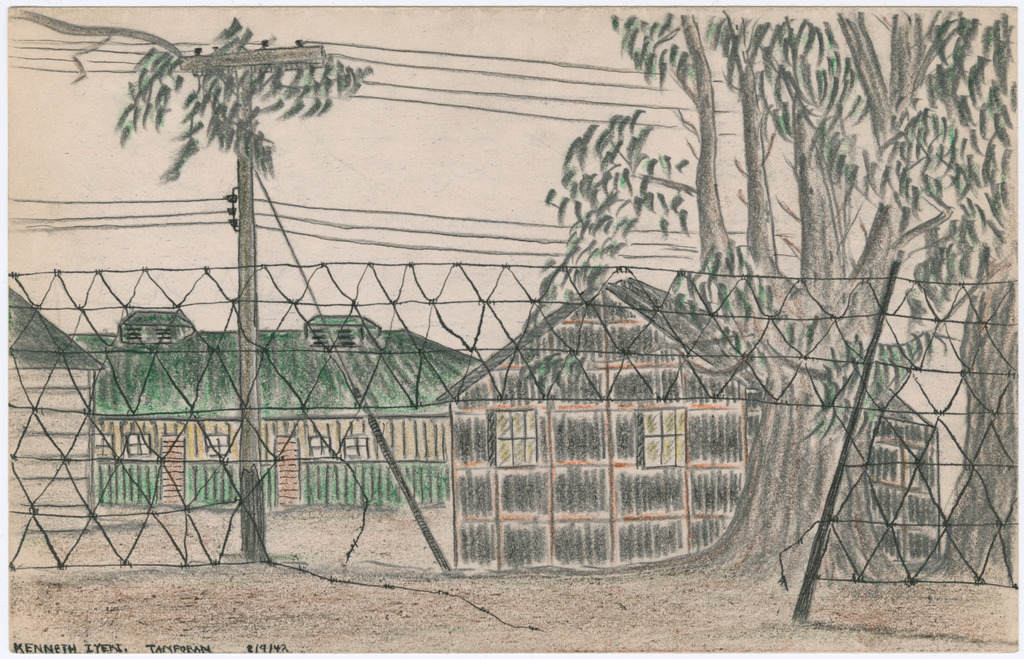

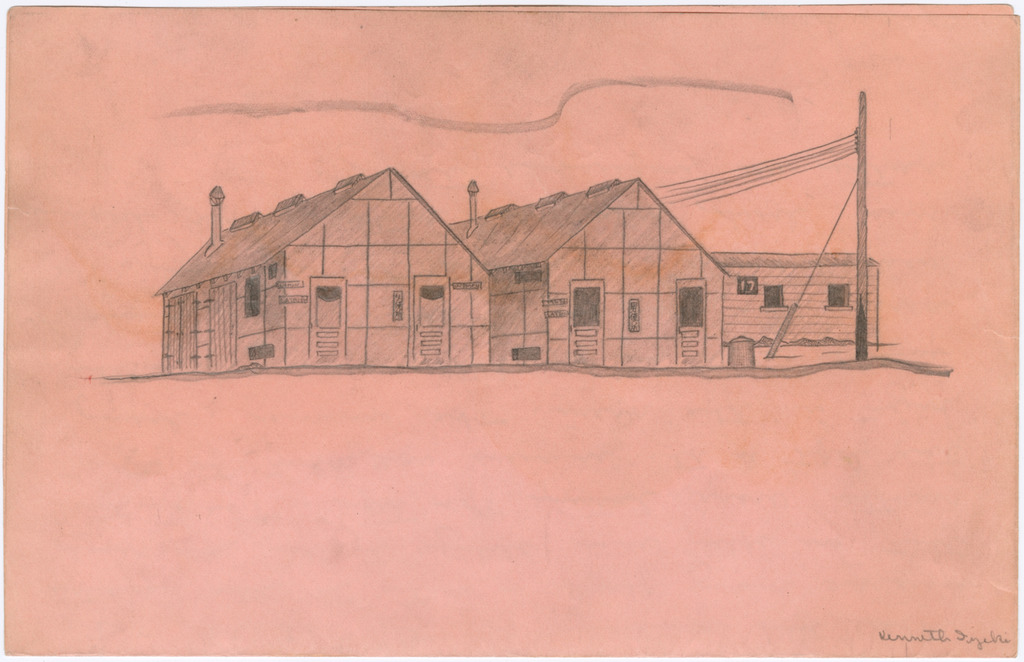

VO: The facilities eventually got better when the incarcerees got to the more permanent WRA concentration camps—but not immediately. The WRA had to build ten cities from the ground up. Here’s Dr. Connie Chiang, author of Nature Behind Barbed Wire: An Environmental History of the Japanese American Incarceration:

CHIANG: These camps were sort of, for the most part built from scratch. And so the WRA was looking at housing 8000 to as many as 18,000 people in these camps.

GEORGE KATAGIRI: It’s composed of hundreds of barracks, hundreds of barracks, and they were divided into blocks, and each block had two rows of about seven barracks. And in the center of those rows were the latrine and the showers and the laundry and things of this type.

CHIANG: And obviously, there, there was a great deal of infrastructure that was necessary. So not just sanitation and sewage systems, but water supply, electricity, plumbing, all of those things needed to be developed.

VO: One of the first things the Army Corps of Engineers had to do when it was evaluating potential sites was figure out where all that waste was going to go.

CHIANG: In general, there would be some method of taking the waste from the latrines elsewhere in the camp to some sort of centralized sewage treatment plant. And then from there, the sewage would be treated. Sometimes it’s chlorinated, then from there discharged onto the land in some way or into some sort of water source.

VO: Sanitation is a major concern in an ordinary city, but when one pops up almost overnight? It was a nightmare.

CHIANG: Simply the camps were built very fast. And sometimes the quality of materials they used was not top notch, given that there are many material shortages during the war. And so that created problems, there is simply the fact that, you know, you’re thousands of people living in these camps, so that created problems as well.

VO: The latrines often weren’t finished when the incarcerees arrived.

HISA MATSUDAIRA: We got off the train, they were still putting in the sewer and they were still putting in the pipes and things like that.

ISAO KIKUCHI: There were outhouses at the time.

TAKETORA JIM TANAKA: Because they were laying that sewer line, the water line, and all that.

TOSHIKAZU “TOSH” OKAMOTO: I guess they tried to build things so fast that the sewage system wasn’t working and oh, it was really, really smelly in the latrine. [Laughs]

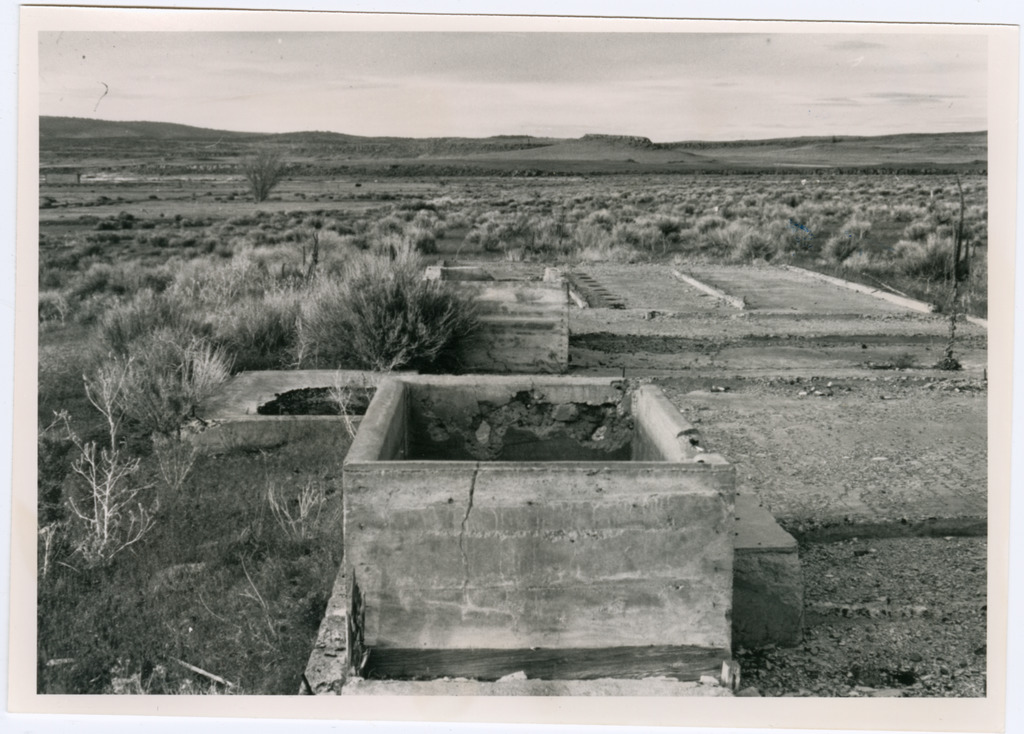

VO: By the end of September at Granada, 29 blocks were populated, but only 12 had plumbing. When toilets were used before the water had been connected, “a clean-up hose squad” was created to deal with the mess. At Minidoka, the sewage system was not fully operational in August 1942 when the first incarcerees arrived—or four months later in December. The residents were still using outdoor latrines in Idaho during a time of year when the average high is 27 degrees Fahrenheit and the average low is -2.

HENRY SAKAMOTO: For about the first year, we didn’t have a sewage plant, so the option was outhouses, different outhouse for men and women and each block had two… and I think they were six-seaters.

SAKAMOTO: By springtime, you had to dig new holes for the outhouses and cover up the old holes because they were getting pretty full. I think it was almost a year before we had sewage facilities.

VO: And then there were maintenance problems.

CHIANG: Sometimes pumps would break down. There would be clogs, there would be sewage backups.

VO: As the camp populations grew, so did the strain on these systems.

CHIANG: At Topaz, the effluent was discharged into a slew that was about a half mile from the center of the camp. And this indeed created a nuisance—at least a nuisance that the WRA officials were aware of—because of the odor, and also because it was a breeding ground for mosquitoes. So they eventually began to drain the slew into another ditch, which was another couple miles from the center. And this, this confined the water to a smaller area and sort of helped keep the mosquito problem under control.

VO: At Tule Lake, says Jimi Yamaichi, who worked as an engineer:

JIMI YAMAICHI: We had almost 20,000 people living there. And the well system was made for 15,000 people, and it was part of our job to watch the water intake into the camp, the excess sewers and power and so forth. But the sewer, we couldn’t take care of that, so they built an extra sewer plant later, but we just flood, hundreds of acres was just flooded out there, raw sewer out there.

VO: Sewage could cause or spread diseases if it wasn’t disposed of properly. It attracted mosquitoes and other bugs. It could get into the groundwater or start leaking into the streets. Yeah, that actually happened at Gila River.

CHIANG: One of the pipes failed. So there are large pools of sewage that formed in the camp. And so the WRA staff had to use bulldozers to turn over the sewage, mix it with sand and dirt. The Japanese Americans who are living in the camp at the time, had to sort of navigate around these open ditches of sewage, there are planks placed over some of the open the open ditches and so on and so forth.

VO: This was unpleasant during the day, but if you had to use the latrines at night, these ditches could become… perilous.

CHIANG: When Japanese Americans were perhaps out at night where they couldn’t see very well, possibility that they might fall into an open open ditch of untreated sewage.

VO: In fact, the road was fondly dubbed “sewer lane” by young people at Gila. And that wasn’t the only place that got a nickname based on its proximity to the sewers. Yukio Kawaratani lived in block 34 at Tule Lake.

YUKIO KAWARATANI: we were on the corner of the camp, which was close to the effluent or sewage treatment plant. So it was pretty stinky. In fact, the blocks in that portion of the camp were called “Sewer Heights.” [Laughs] You get used to the smell, but whenever you had visitors, they’d always say, “How can you stand the stench?” But anyway, that’s where we were.

VO: The sewage accumulated in a pond out on the edge of camp. In the winter, that pond froze.

BETTY FUJIMOTO KASHIWAGI: I remember my tap dancing teacher, we used to skate on the sewer pond, and she fell through and I laughed my head off. [Laughs]

VO: The toilets and showers and sinks required constant cleaning.

MASAMIZU KITAJIMA: My mom, because she had five kids, she felt during the day she had to be with the children, take care of the children. She would work at night, when the kids were sleeping, or she could work sometime when she didn’t need to watch the kids. So she took the job as a janitor to clean the latrines, both the men and women’s latrines and the showers.

VO: And the boilers had to be maintained, or the pipes might freeze and—if it got cold enough—burst.

HENRY SAKAMOTO: My dad was in charge of the boiler room, and he’d keep the fires going for the hot water, for the laundry, and the shower rooms, coal burning furnace. He’d take care of that during the day.

VO: At Minidoka, the administration tried to cut the number of boilermen and janitors in summer 1943. The increased workload was somewhat manageable during the summer, but less so during the winter when boilers had to be maintained at all hours.

CHIANG: The boiler men and the janitors essentially went on strike. Minidoka was called upon to reduce its workforce—this was coming from the National WRA office, and they were telling all the camps that they had to reduce the number of employees. So the Minidoka officials decided that they were going to cut down on the number of boiler men and janitors in all of the blocks. This was a big deal in the winter, because, you know, in Idaho, it was cold, and you needed the boiler men to maintain the heat in the latrines, make sure that the pipes didn’t freeze, make sure that there’s access to warm water. And in addition, they also had to take on additional duties of cleaning the latrines.

VO: The strike was unsuccessful. The WRA refused to budge and when community leaders, suffering from the lack of heat in the bathrooms during the Idaho winter, asked the boilermen to return to work, they reluctantly did. But even with the boilermen working, the latrines were freezing.

HOPE OMACHI KAWASHIMA: It was cold, there was no heat at all in the bathrooms.

VO: And the trek to and from the latrines in the middle of winter was unpleasant to say the least.

SAKAMOTO: In the wintertime, that first winter, was kind of tough, and you would resist having to go to the bathroom for as long as you could because it was so cold and windy.

KUDO: You couldn’t go in the middle of the night in your pajamas all the way to the communal bathroom.

AKIKO KUROSE: Because our toilets and bathrooms were way far away and in the middle of the night, people didn’t want to go in the freezing cold to go to the bathrooms.

VO: But the incarcerees came up with a solution. The chamba.

TAKESHI NAKAYAMA: My father had set up a big bucket to use as a chamba, indoor toilet thing for the little ones.

VO: More commonly known as a chamber pot, “chamba” was the Issei transliteration of the term.

ELSA KUDO: My father pronounced it “chamba.”

KUROSE: One of the most popular things that people purchased, and the stores kept running out of, was chamber pots.

VO: Heather Harano’s family came prepared.

HELEN HARANO CHRIST: And we had to wait ’til we were called, and then we carried only the things that we had. I always carried the chamber pot. My parents knew that that would be an important thing for our family.

LOUISE KASHINO: And most of us purchased chamber pots, so we wouldn’t have to go out at night.

ELSA KUDO: He bought a chamber pot for us children.

YOSHIKO KANAZAWA: I was six and a half … For me it was too frightening, so I used a little chamber pot in our barrack.

VO: The chamba was helpful for many, but it was absolutely indispensable for Betty Sakurai, who used a wheelchair to get around. Her brother Richard explains:

RICHARD SAKURAI: She couldn’t go any further than that because the wheelchair wouldn’t go up and down the stairs. And if she got down to the ground, of course it was muddy, so she couldn’t leave the room. There weren’t any bathroom facilities in the barracks so my parents asked me to build a little chair for my sister that they could put a chamber pot underneath. So somewhere or other I found some tools, so I gathered pieces of lumber together and built a chair and cut a hole in the seat of the thing there and measured underneath it just enough so that the chamber pot would just slip underneath the hole and that my sister could use that as a toilet. I did that at the assembly center and at Minidoka.

MARGIE Y. WONG: You know my dad was elderly, for having somebody my age. He was fifty-five when I was born. When you get old you have to urinate in the evenings. And when it was snowing and everything so I remember my mom had a bottle and she would put it there for him

VO: Chambas don’t exactly clean themselves.

WONG: And in the morning it was the girls’ duties to go and, and empty it out.

ELSA KUDO: The shi shi would freeze in the winter, that’s how cold it was.

LOUISE KASHINO: It was our duty to clean out the chamber pots in the morning, you know. [Laughs]

MAS OKUI: My little brother always had to take the chamber pot out.

OKUI: My older brother and I never took the chamber pot, the chamba, we never.

OKUI: [Laughs] You didn’t want to be seen carrying it.

VO: Some chambas were, uh, multi-purpose.

YUKIKO MIYAKE: There was a lady that used to make otsukemono in the chamber pot. And when I was sick, this lady was kind enough to make some otsukemono for me and bring it over, [laughs] and my friends wouldn’t let me eat it because they said, “How can you? How do you know she didn’t make a boo—you know, make a mistake?” So I never ate her otsukemono, but I always had to tell her how nice it was and thank you very much. I never knew who the lady was, but she was always bringing otsukemono over, but my friends said, “No don’t touch it. Don’t touch it.”

VO: Food wasn’t the only thing you could make in a chamba.

GEORGE ISERI: One thing they wouldn’t allow was liquor in the camps. I had a good friend that, so he went and sat on his army cot, and he reached under the bed, pulled out a chamber pot, took the lid off and gave us a cup and said, “Here, have a drink.” [Laughs] These are brand new pots, he says, so we had a drink of wine out of this chamber pot.

VO: But for the most part the chamba had one specific—and important—purpose.

YUKIKO MIYAKE: The Issei ladies always had a chamber pot.

YUKIO KAWARATANI: So the females could, instead of walking to the toilet could go there at night.

AMY IWASAKI MASS: My mother would need to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night, so she had a chamber pot like many women. And as kids we made a lot of fun of chamber pots.

KAWARATANI: Of course, it was metal, so when they put the cover on, it was a big clank, but everybody pretended not to notice.

MARY HARUKA NAKAMURA: —and we could hear the chamber pots clanging.

VO: Embarrassment aside, these Issei women—and anyone else who used the chamba—were onto something. Navigating your way to the latrine at night was not easy. It was dark—unless the guard’s spotlight was following you—and incarcerees were not allowed to carry flashlights or lanterns, Chiang explains.

CHIANG: There’s a story of a man who basically got lost, he was wandering out around outside looking for the latrine. And he wandered around for about an hour before he finally found shelter in another dining hall.

VO: The chamba was also more convenient.

TAKESHI NAKAYAMA: I guess it smelled bad, but I don’t know. Beats going all the way to the toilet, wherever that was.

VO: Especially because you never knew who might be watching in the latrines.

BETTY FUJIMOTO KASHIWAGI: And then one time when we were taking a shower, my girlfriend who was on the shy side, I said, “Hey, Nancy, that guy’s looking at you through his peephole.” Because we had a boilerman that adjusted the temperature of the water.

LOUIE WATANABE: You try to look at, peeping tom, and other side, “What are you doing over there?” [Laughs]

TED HACHIYA: But the girls found out that there were peepers up there.

INTERVIEWER: And then what?

HACHIYA: They used to holler in unison.

INTERVIEWER: What did they holler?

HACHIYA: “Peeping Tom.” [Laughs] God, it was funny. You should have heard all the fire guys scurry off the roof.

VO: But these situations were really nothing to laugh at. Here’s Nina Wallace, who has written about sexual assault in the camps for Densho:

NINA WALLACE: The latrines were a big site for sexual harassment, for, in some cases, even assaults. And, you know, just a lot of kind of generally creepy behavior that maybe wasn’t documented.

VO: Sexual assault and rape were both under-reported and covered up by the WRA and other incarcerees.

WALLACE: You see women working as secretaries or clerks, or hospital aids, but, you know, you don’t see as many women, for example, working for the Japanese Evacuation and Resettlement Study, which is where a lot of this information about sexual violence came from. And you don’t really get the perspective of people who maybe have experienced this or have a closer knowledge and understanding of what sexual violence looks like. So you see a lot of people kind of dismissing stories, dismissing that as rumors or even cases where you see people excusing, excusing rapes.

VO: Mae Tsubouchi’s story is a heartbreaking example of how the community at Poston and those placed in charge of chronicling the incarceration dismissed or excused sexual violence.

WALLACE: Mae was 24. She was incarcerated in Poston with her dad. And she had dated this older man who worked in the mess hall with her. She ended this relationship, and her ex did not take kindly to this. He for months after they broke up, would stalk her around the camp, would threaten her, would force his way into her barracks to try to get her back, I guess. Finally after a few months of this, he snuck into her room while she was sleeping and stabbed her multiple times. And she, after a few days in the hospital, died.

VO: Her murderer escaped into the desert. A search party went after him but he was never found.

WALLACE: In the notes from Richard Nishimoto, who was one of the field workers for JERS, and he describes what happened to her, but there’s just no sympathy for this woman. You know, he has several pages of his journal and he just talks about essentially her sexual history and her physical appearance. And that’s really all that he had to say about her.

VO: Sometimes family members also pressured victims to excuse or legitimize sexual violence.

WALLACE: There was one case where there was this teenage girl, I think she was maybe like, 14, 15, something like that. And she was pregnant after, being raped by, I think a family friend. And it was something that had gone on for a couple of years before she became pregnant. And her father actually was pressuring her to marry this man who had abused her to, I think the phrase that he used was ‘to legitimize the child.’ This girl actually, even though she was facing all of this pressure from her family, she actually she didn’t give into it. She did not decide to marry her rapist. I have no idea what happened to this girl from, that’s kind of where her story in the record ends, but it takes a lot of courage and a lot of bravery to advocate for yourself in that situation.

VO: Dr. Tamie Tsuchiyama’s field notes for the Japanese Evacuation and Resettlement Study describe how dangerous the latrines specifically could be. Tsuchiyama was the only Japanese American woman to work full time for the study.

VO: On December 16, 1943, Tsuchiyama, then a graduate student, wrote, “last night one middle aged man sat in the women’s latrine of his block. There was a girl taking a shower; then, another girl about 16 years of age came into the latrine. He approached this girl, flashed a five-dollar bill, and asked her to ‘go to bed’ with her.”

VO: “She was frightened and stood still for a moment. The man left but the girl was too frightened to leave the latrine. When the other girl finished her shower, the two left together. They saw the man still lurking in the darkness at the corner of the building. The man was briefly confined in jail and then released on farm work.”

HANK SHOZO UMEMOTO: —and we knew about it, but it was something that was, you know, not talked about.

VO: At Tule Lake, a group of men attacked the women in one of the latrines.

WALLACE: A group of kibei turned off the electricity to a women’s latrine and then actually went inside and raped the women who happened to be inside the latrine. And it sounds like it was multiple victims and multiple rapists. And it was something that—it sounded like everyone in the camp knew about and heard about after the fact and after that women would not go to the latrines alone, like, they would always be accompanied by a husband or a father. Because it wasn’t safe to go on your own.

VO: Sumiko Yamamoto remembers taking precautions when using the latrines at Tule Lake.

SUMIKO M. YAMAMOTO: Late at night, if you’re taking a shower or if you’re using the bathroom, somebody would come in, sneak in.

YAMAMOTO: You’d get assaulted. They would assault you. So they said, “Don’t ever go late at night.”

VO: All of this made bathing an extremely stressful experience.

YAMAMOTO: —they have holes in the roof or something.

VO: Before camp, Japanese baths, or ofuros, had been an important relaxation ritual in Japanese families.

GEORGE NAKATA: And to a lot of Japanese, taking a bath or taking a shower is not simply getting clean, but it’s relaxing, it’s soothing. It’s really a period of the day to kind of unwind.

TOSHIRO IZUMI: They’d undress, wash themselves outside, and then they’d get into the ofuro and they soaked themselves real well. And I believe that’s one of the enjoyment they had.

VO: Historians have traced bathing in Japanese culture back as far as the third century. Both Shinto and Buddhist traditions used baths for religious purification. Baths were also thought to heal everything from diarrhea to colds to skin diseases, arthritis, nerve damage, muscle pain, high blood pressure, and mental health issues. On top of that, it was a great way to relax, as several have pointed out.

YASUI: Those baths were the greatest things, you know. They were very relaxing. What you do in the Japanese tradition is you soap yourself and wash yourself and rinse yourself off real thoroughly outside of the tub, and then you get inside the tub to soak and relax.

VO: Yuriko Yamamoto enjoyed baths in the ofuro before camp, but even after an ofuro was built at Heart Mountain, she was afraid to use it.

YURIKO YAMAMOTO: They said there was a peeping tom, so I was kind of afraid to—

VO: Camp took that small pleasure away from her too. But some did find ways to enjoy a bath—even in camp. In some cases, people put barrels in the showers to use as a tub.

KAZUKO MIYOSHI: And we had one room that was a shower, and you had the little barrels you could use as a tub—

VO: In a pinch, the wash basins in the laundry room would do as a tub for little kids.

LAURIE SASAKI: In the washhouse there were these double vats. And because, you know, we were kids, we’d just go in there at nighttime and take baths in there. We’d fill up both tanks and then put our feet on one side and the body on the other and that was our furo. And we’d just shut the light off and make sure that nobody else came by there and we’d take our baths.

KAZUKO MIYOSHI: —and then eventually people built a Japanese-style bath.

VO: Of course these didn’t begin to compare to the ofuros some families had before camp.

GEORGE NAKATA: A wooden Japanese bathtub with a live fire underneath.

HOMER YASUI: This is a Japanese style bath which is usually made in an outbuilding, and the way you do that, it’s in a different building by itself, and they have a, usually, a concrete tub, could be metal, and the bottom of it they’d have, they’d have slabs of iron, and they’ve actually build a fire underneath it, and you boil the water in this tub.

VO: But in camp, you made do with what you had. And what they had at Manzanar was lots and lots of cement.

SUE KUNITOMI EMBREY: In our block we put a Japanese soaking tub. They bought the cement and made a what we call a ofuro, and people would wash themselves under the shower and then go in and soak in the tub. And then it pretty soon became sort of a socializing method for our older generation. They were kind of taking over the custom that they have in Japan.

VO: Eventually, the latrines and showers were relatively finished: flush toilets and partitions for the women.

SUMIKO M. YAMAMOTO: When you take a shower, they have no partitions, and the bathrooms, they had partitions, but they were up to here. [Laughs]

VO: Even with these improvements, the latrines left much to be desired. We asked around to see what other latrine stories were out there. Matthew Hashiguchi replied on Twitter that he remembers his grandmother talking about quote “the v-shaped cut outs in the wood plank toilet seats.” His grandmother told him, “They knew to never sit at the end of the row because you’d get splashed with sewage when someone flushed.” Ew. And, of course, even after the latrines were finished, the weather could still make using them an… uncomfortable experience.

WILLIE K. ITO: Of course, we had to go to the latrine, and some of those winters were so harsh, and you would leave your barracks, trudge over to the bathhouse and the latrine, take a shower or take a bath or whatever, and then you have to trudge back to your barracks.

VO: Snow wasn’t the only problem. There was also the dust.

JAMES NISHIMURA: The dust was just as brutal as the cold.

HISA MATSUDAIRA: It was very, very dusty. And so the first thing we hit, I think was, a dust storm. And it was like being sandblasted. You have to get down like this, close your eyes, close your mouth, and just scrunch down. Still you’d get all that dirt and sand and everything.

SHARON TANAGI ABURANO: And the dust is something unlike anything you ever saw. It’s light because it’s lava, old lava dust, and this is why we had trouble. When it rained, it turns to this shoe-pulling mud, you know.

NISHIMURA: You’re always slopping in mud.

VO: The incarcerees developed ways of dealing with the mud too.

JAMES NISHIMURA: I remember the older men, members of the community, they made wooden clogs—

CHORUS: Getas.

TOMIKO HAYASHIDA EGASHIRA: out of scrap wood—

JUNE TAKAHASHI: about two inches high—

EGASHIRA: that you wore so you won’t get all muddy—

TAKAHASHI: It was so muddy. I remember one time that the thong broke on that was holding your toe and that held onto the geta, you know, and I stepped right into the mud and was ugh, it was terrible—

VO: That wasn’t the only benefit of getas.

SHIG YABU: Well, I had the worst case of athlete’s feet, because we had an open shower facility… but it doesn’t take much to have that spread, rampant, everybody gets it, you know.

KAZUMI YONEYAMA: We did wear getas in the showers, so that our feet wouldn’t touch the concrete, but I think that was mostly to prevent getting athlete’s feet.

YABU: —so we start all wearing getas, with scrap wood, we all made getas, and that worked great.

WILLIE K. ITO: Some of these artisan guys were fantastic. They would fashion beautiful getas with the straps that were beautifully knitted and formed and whatever with stuffing so it didn’t hurt your feet. And all of these artifacts that were created out of necessity, but at the same time very artistic. The wood was polished and it was lacquered, and beautiful. And then, of course, you had the utility getas that kept your feet out of the mud coming from the bathhouse and all that.

WILLIAM R. JOHNSTON: Clop-clop-clop-clop. Quite a distinctive sound.

ITO: So that’s another thing, I marvel at the ingenuity of some of these people that made life much easier.

VO: Living in the camps was humiliating. The loss of freedom, being suspected of being the enemy and the ever-present threat of sexual assault that never went away—the big things. Then there were the latrines with no partitions. Food poisoning. Neighbors hearing your every move, word, and… fart. A gross, undignified, anxiety-inducing nightmare. Waiting in line in the dead heat of summer with a belly full of tainted macaroni salad. Carrying the chamba down Sewer Lane, hoping its unspeakable contents didn’t slosh onto you. Winding your way around ditches of raw human waste that formed in the streets. And in the face of all those humiliations, were the cardboard boxes that women carried with them to the latrines, the block’s cement ofuro, the handcrafted geta, and the people behind them—the old men who lovingly crafted scrap wood into shoes, the girls who kept lookout for one another when they had their periods, the friends and family members who protected one another in the latrines, the boy who built his sister a toilet because her wheelchair couldn’t navigate the dust, mud and snow. This is a story about the lavatory. And that story is humiliating and heartbreaking and flawed and resilient… and sometimes just plain funny.

VO: You’ve been listening to Campu. Please subscribe, like, share, review—on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you’re tuning in; we love reading the reviews and hearing your feedback! Or hey, just pass the word along. And a big, big thank you to everyone who’s helped out so far! Visit densho.org/campu for additional resources and this episode’s transcript.

VO: Campu is produced by Hana and Noah Maruyama. The series is brought to you by Densho. Their mission is to preserve and share the history of the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans to promote equity and justice today. Follow them on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram at @DenshoProject. Support for Campu comes from the Atsuhiko and Ina Goodwin Tateuchi Foundation. Special thanks to Natasha Varner, Brian Niiya, Nina Wallace, Naoko Tanabe, Andrea Simenstad, and Connie Chiang for their assistance with this episode. This episode included excerpts from more than 70 Densho oral histories as well as interviews conducted by Frank Abe for his film Conscience and the Constitution. The names of the narrators featured in this episode are: Marian Asao Kurosu, Rokuro Kurihara, Masako Murakami, George Azumano, Frank Yamasaki, Mika Hiuga, Akiko Kurose, Dorothy H. Sato, Hiroshi Kashiwagi, Jim Kajiwara, Lucy Kirihara, Taylor Tomita, Henry Sakamoto, Dorothy Kuwaye, Etsuko Ichikawa Osaki, Sachi Kaneshiro, Cherry Kinoshita, Hope Omachi Kawashima, Isao Kikuchi, George Iseri, Betty Fujimoto Kashiwagi, Keiko Kageyama, Grace Watanabe Kimura, Sue Kunitomi Embrey, Mas Okui, Louise Kashino, Victor Ikeda, Peggie Nishimura Bain, Frank Kitamoto, Toshikazu ‘Tosh’ Okamoto, Min Tonai, Helen Tanigawa Tsuchiya, Hikoji Takeuchi, Fred Oda, Lily Kajiwara, George Katagiri, Hisa Matsudaira, Taketora Jim Tanaka, Jimi Yamaichi, Yukio Kawaratani, Masamizu Kitajima, Elsa Kudo, Takeshi Nakayama, Helen Harano Christ, Yoshiko Kanazawa, Richard Sakurai, Margie Y. Wong, Yukiko Miyake, Amy Iwasaki Mass, Mary Haruka Nakamura, Louie Watanabe, Ted Hachiya, Hank Shozo Umemoto, Sumiko M. Yamamoto, George Nakata, Toshiro Izumi, Homer Yasui, Yuriko Yamamoto, Kazuko Miyoshi, Laurie Sasaki, Sumiko M. Yamamoto, Willie K. Ito, George Katagiri, James Nishimura, Sharon Tanagi Aburano, June Takahashi, Tomiko Hayashida Egashira, Shig Yabu, Kazuko Yoneyama, William R. Johnston, Yasuko Miyoshi Iseri.