July 4, 2020

In this guest post, scholar and Soto Zen Buddhist priest Duncan Ryūken Williams reflects on celebrating his first 4th of July as an American citizen in the midst of a global pandemic and uprisings against anti-Black police brutality. He illustrates how the concept of interconnectedness can illuminate our understandings of history and various forms of oppression, but also guide our collective work towards liberation.

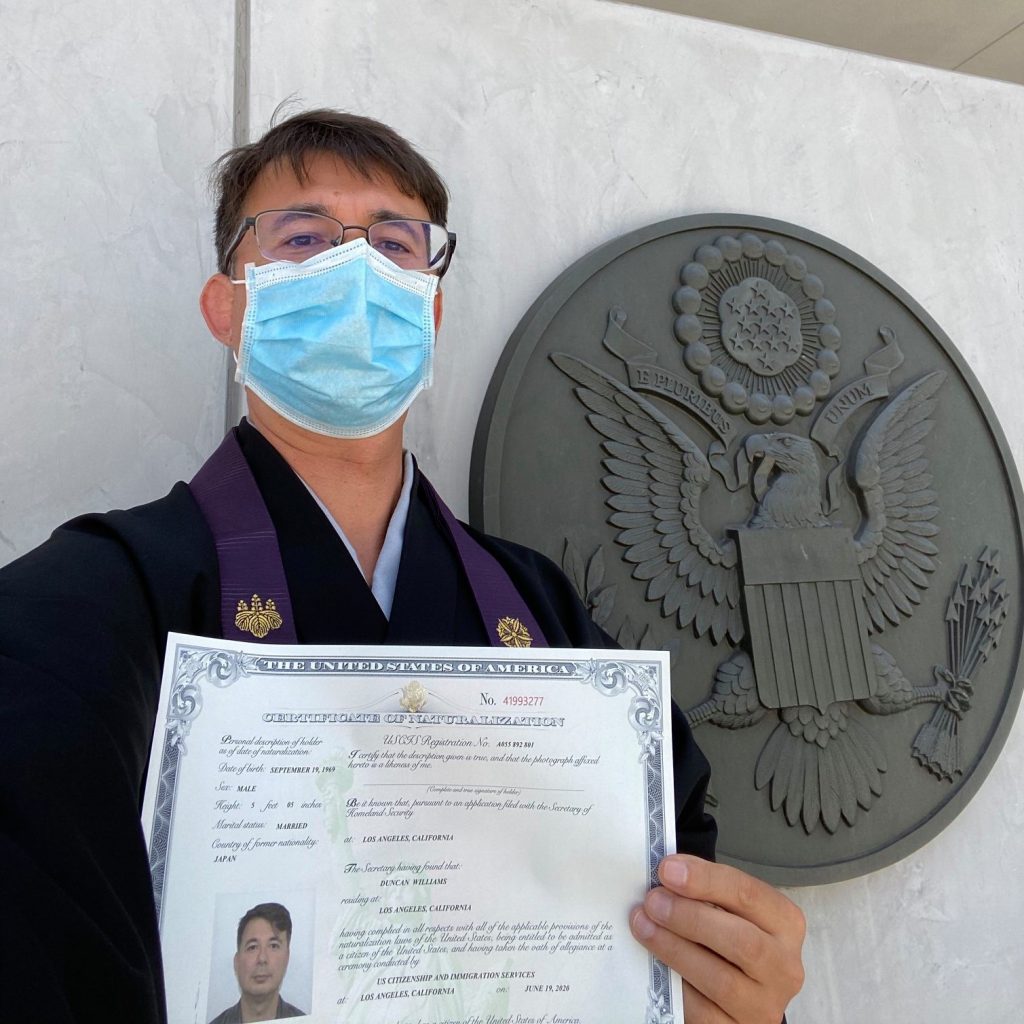

In the section under COVID-19 safety precautions, the Department of Homeland Security letter addressed to me mandated face masks and banned guests for my newly re-scheduled naturalization ceremony. Given fears that the virus might serve as a pretext for a complete shutdown of immigration and naturalization, it was a huge relief to find out that the ceremony would take place at all. The original date for the ceremony had been scheduled for March 19, the very day that California governor Newsom issued a statewide stay-at-home order.

I had always imagined this conclusion of a long path towards citizenship would take place in a room full of people from all corners of the world, celebrating together with their loved ones. Instead, when I arrived at the Federal Building at the appointed hour on June 19, I was told to observe the prescribed physical distance, marked out on the floor in tape, from the others waiting, like me, to be naturalized. The line was short: one person in front of me, and one person behind me. But standing there, waiting my turn to go in front of an official seated behind a piece of plexiglass, it occurred to me that what this version of a citizenship ceremony lacked in scale and pomp, it made up for in an almost schematic clarity. Before the person ahead of me in line was another, no longer visible person who had likewise gone through this process. And behind the person behind me was another not-yet visible person who would undergo this process after me.

Because we were all wearing masks, I could only hazard a guess as to what circuitous path might have brought these fellow applicants to the Federal Building that day. In turn, they might have wondered who I was. I come from a family of entangled roots – a Japanese mother and a British father. Born in Japan, I crossed the Pacific Ocean from Japan, the country of my birth, to the United States, the country I would come to call home, thirty-three years ago.

Being an ordained Soto Zen priest, I had decided the best way to comply with government directives for formal wear would be to wear Buddhist robes. It would be a small but significant way for me to assert my right to the religious freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution at the very moment I pledged to support and defend it.

Despite the physical distance between us, the anticipation of whatever transformation citizenship entails was palpable. An invisible thread of connection – as immigrants to this country, waiting for our chance to walk into a new sense of possibility and belonging – was all too apparent even behind those face-obscuring masks. We had not planned this crossing of paths at this particular place in this particular moment. Yet here we were: in relationship with one another.

What struck me most at that moment was how this line towards citizenship illustrates a central truth of Buddhism: interconnectedness. We might not choose every aspect of how or why we are connected, but that doesn’t lessen the linkage, which extends backwards and forwards in time, through people and generations and histories. Who we are right now is the karmic linkage between the past and the future.

There’s an image from the Buddhist tradition’s sacred texts that is often used to help explain this concept of interconnectedness. Imagine the universe as an infinite net of jewels. Each jewel has been cut in such a way that if we care to look deeply enough, we can see reflected in it all of the other jewels. Likewise, each of us is also reflected in the mirrored surface of every other jewel. This image of a net of jewels teaches us that we are constituted by everything and everyone around us. Understanding this demands a certain acknowledgement of mutual dependence and responsibility. Regardless of whether or not we are affirmed by governments as citizens of a nation, we inherit the legacy of those who have lived there before us.

This collective karma necessarily leaves an imprint on our present moment. The oath I took to defend and support this country took place on Juneteenth. And not just any Juneteenth – but Juneteenth 2020, a date marked nationwide and worldwide by protests demanding justice for Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, David McAtee, and so many others whose lives have been extinguished by police violence and vigilantism, undergirded by anti-Black racism.

What is revealed by looking deeply into the mirrored jewel of this moment? Juneteenth as a holiday was originally created to celebrate news of emancipation finally reaching Galveston, TX, the last corner of the nation where it had yet to penetrate, a full two years after it had been signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln. In the jeweled mirror of Juneteenth 2020, and the protests that it was marked by, we can see the reflection of that first Juneteenth, in both the systemic disregard for the lives of Black Americans and the struggle for transformation that has come in response to it. In the mirror of my citizenship is the realization that the Constitution to which I was pledging my loyalty is shaped as much by a legacy of delay, of independence deferred, as the promise of freedom.

It took former slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass to interlink the struggle for emancipation with immigrant inclusion, two years after the first Juneteenth. In his 1867 Boston speech on the “character and mission of the United States” – given as his response to rising agitation nationwide against the so-called “heathen Chinee,” that would ultimately led to the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first federal immigration ban targeting a particular race or religion – he made a powerful argument for America as “a composite nation.”

Douglass’s vision of the United States was one that welcomed the Chinese and immigrants of a multitude of races and faiths to the “duties of citizenship,” while reminding us that slave labor was foundational to the wealth of our nation, a prosperity that makes the U.S. an attractive destination for immigrants in the first place.

In Douglass’s recognition of the interdependence of slavery and exclusionary immigration policies, he intuited the dangers of seeing the nation as unchanging and static. American-style chattel slavery – the commodification and enslavement of individuals and their descendants in perpetuity – requires belief in the fundamental immutability of race in order to legitimate segregation and exclusion. The anti-Blackness of our times, just like the Muslim travel bans or the calls to build walls on the southern border, are merely the latest manifestation of a long tradition of conflating American belonging with a singular or supremacist racial and religious identity.

For me, as a person of Japanese ancestry who has chosen to become an American in these uncertain times, it’s impossible not to think of my citizenship in the context of the incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII. Buddhist priests like myself were the first people picked up for internment by the FBI, one of the more egregious examples of religious or racial targeting of a particular group on the pretext of national security. After the community leaders came the mass incarceration of 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens, into concentration camps.

It didn’t matter if you were an elderly grandmother or someone who had served in the U.S. military, the architects of the ethnic cleansing of the West Coast proclaimed that anyone with a single drop of Japanese blood, including mixed-race babies from orphanages, was subject to indefinite incarceration in camps surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards.

This too is a part of my karmic inheritance – yet another link in the story of what it means to be American. All part of a single net of jewels, none of it extricable from any other part. So when I look into the mirror of George Floyd, murdered by a police officer who knelt on his neck in 2020, I simultaneously see Kanesaburo Oshima, a store owner shot by a guard in the back of the neck as he longed for home at the Fort Sill Internment Camp fence line in 1942.

George Floyd left behind five children; Oshima, eleven children. Through them, we see other children, separated from their families and detained on the U.S. southern border, and we see Johanna Medina Léon, an El Salvadoran transgender nurse and asylum seeker who died in an ICE immigration detention facility after being denied medical care. And when we look into the jeweled mirror of Léon, we can also see Bawi Cung, stabbed in a Sam’s Club in Texas by a man claiming that Chinese people were spreading the COVID-19 virus.

But along with struggle comes support. Being interconnected means that however isolated and autonomous we might think we are, we are not alone. We are interdependent.

When Japanese Americans returned to the West Coast as the WWII U.S. concentration camps began to close in 1945, many faced lingering racial animus. In Los Angeles, they found an unexpected friend in Roy Loggins, a Black business owner who ran a food catering company for Hollywood studios. While people of Japanese heritage were being refused housing and job opportunities by white landlords and employers, Mr. Loggins went out of his way to share left-over food from catering events and even offered part-time work to members of the Senshin Buddhist Hostel, a refuge for former Japanese American incarcerees who had nowhere to call home. His acts of kindness were so seared into the memories of those whom he helped, that not only they, but their children, remember him with gratitude more than fifty years later.

We think freedom is about independence, but actually freedom is about interdependence. As I celebrate my first Independence Day as a U.S. citizen, I join a lineage of American ancestors, some celebrated and others, like Roy Loggins, less well-known, who have taught us that the project of emancipation in America cannot be accomplished alone. That the journey to liberation extends across generations and communities. Even if we are masked and standing apart, without friends or family in a line to become a citizen, we are simultaneously surrounded by all those who have come before us and all those who will come after us. All of us inexorably tied together, every single one of us implicated in the struggle to actualize freedom.

—

Duncan Ryūken Williams is Professor of Religion and East Asian Languages & Cultures at the University of Southern California and Director of the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture. Previously, he held the Ito Distinguished Chair of Japanese Buddhism at UC Berkeley and served as the Director of Berkeley’s Center for Japanese Studies. He was also ordained as a Soto Zen Buddhist priest in 1993 at Kotakuji Temple (Nagano, Japan). Williams is the author of LA Times Bestseller American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War (Harvard University Press) and The Other Side of Zen: A Social History of Sōtō Zen Buddhism in Tokugawa Japan (Princeton University Press) and editor of 7 books including Issei Buddhism in the Americas (U-Illinois Press), American Buddhism (Routledge/Curzon Press), Hapa Japan: History, Identity, and Representations of Mixed Race/Mixed Roots Japanese Peoples (Ito Center/Kaya Press), and Buddhism and Ecology (Harvard University Press).

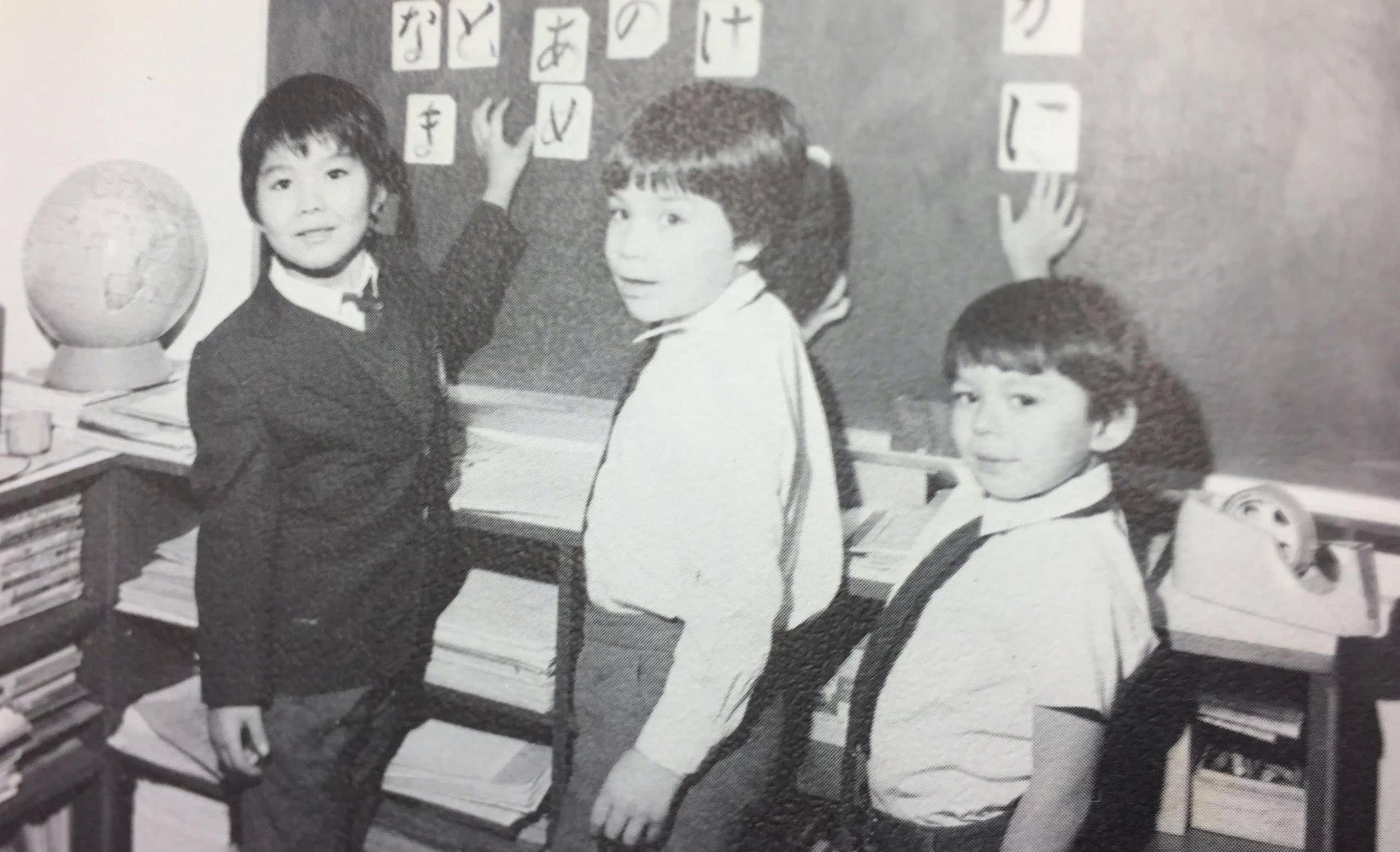

[Header photo: Duncan Ryūken Williams (far right) in his first grade classroom in Tokyo. Photo courtesy of the author.]