October 8, 2019

The Colorado River “Relocation Center”—more commonly referred to as Poston—was located in the Arizona desert a few miles from the California border. The largest and most populous of the War Relocation Authority (WRA) administered concentration camps (with the exception of post-segregation Tule Lake) with a peak population of nearly 18,000, Poston was unique among WRA camps in a number of ways.

First, it was built on the Colorado River Indian Reservation and jointly managed by the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA), a troubled arrangement that ended with the OIA withdrawing by the beginning of 1944. Secondly, it was divided into three different camps, separated from one another by about three miles. It likely had the most rural population, its inmates hailing mostly from farming areas of southern, central, and coastal California. Finally, about two-thirds of its population came directly to Poston without going to an “assembly center” first, something that set it apart from all other WRA camps with the exception of Manzanar. Poston’s Unit I was also the site of a November 1942 mass strike, after the arrest of two Kibei men accused of beating up an alleged informer inflamed existing tensions over the injustice of the mass removal and incarceration. The strike was one of two well publicized blow-ups in WRA camps in late 1942 that influenced WRA policies in the months to come.

Here are ten unique stories about Poston that set it apart from the other WRA concentration camps:

African American Staff

The staff at Poston seemed to have been more diverse than at other camps, with African American workers in particular being more numerous than in any of the other WRA camps. Most held professional positions as teachers, nurses, and welfare and relocation workers. They were seemingly highly regarded by most inmates and staffers. For instance, Chief Nurse Elizabeth Vickers wrote of the African American nurses that “their total contribution to the nursing service surpasses that of both the white nurses and the evacuee nurses that have worked in the same positions that they have held.” But they nevertheless faced racist treatment both inside and outside the camp. Inevitably, some Japanese American inmates inside the fence harassed African American staffers with racial slurs and worse. Outside the fence in Parker, only one restaurant and one bar would serve them.

Labor Strikes

In addition to the mass November 1942 strike in Unit I, there were numerous smaller strikes as inmates rebelled against meager wages and perceived mistreatment by supervisors. Among such incidents was a mass resignation of tractor drivers in Unit I in August 1942; another strike of tractor drivers in May 1943; and a strike of warehouse workers in Unit I in August 1944. Bureau of Sociological Research head Alexander Leighton noted a number of strikes by firebreak and mess hall workers throughout. “Much of the outdoor work was characterized by this kind of dissatisfaction with the nature of the job, the working conditions, the wages, and delays and errors in payment,” he later wrote. “These things led to arguments and minor strikes in which numerous clusters of workers developed feelings of common interest and experience in acting together.”

Draft Resistance

Poston had the largest number of draft resisters of any camp at 106, over a third of the total number of draft resisters at all of the WRA camps. This figure led Poston’s second director, Duncan Mills, to lament that “[w]ith one possible exception Poston’s selective service record was the poorest of any center’s.” Two different tacks for protesting the draft emerged among Nisei. Flyers advocating draft resistance ascribed to “The Voice of the Nisei” appeared in Unit I latrines. On February 21, twenty-eight-year-old Kibei George Fujii—who had earlier been one of the men whose detention led to the Poston Strike in November 1942—was arraigned for sedition as a result. His arrest drew much support, as Unit I blocks donated an average of $61 towards his defense. Jailed in Phoenix while awaiting trial, he was eventually acquitted. A second tack, led by the Committee for the Restoration of Civil Rights of United States Citizens of Japanese Ancestry, advocated military service as a means for demanding civil rights.

Poston also had the highest number of Nisei inducted after the reinstatement of the draft in 1944 at 495.

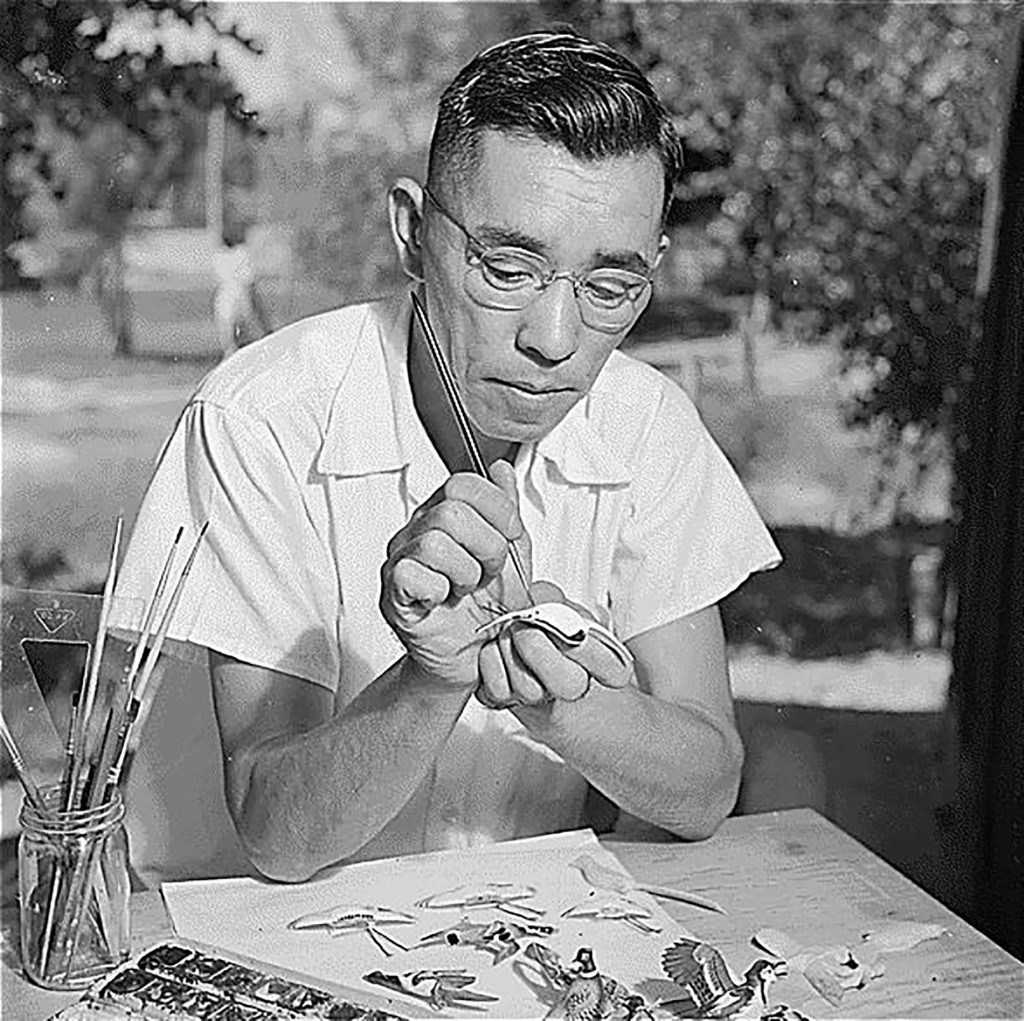

Bird Pins

Hand-carved and painted wooden bird pins are perhaps the best-known craft item made by incarcerated Japanese Americans. Though produced by inmates at every camp, camp folk art chronicler Allen Eaton writes that the bird pins began at Poston and that the Poston pins “outnumbered all others in the quantity and quality of carved and painted American birds.” The bird pins were but one of several craft “fads” at Poston, which also included paper flower making in 1942 and polished mesquite and ironwood sculptures in 1942–43.

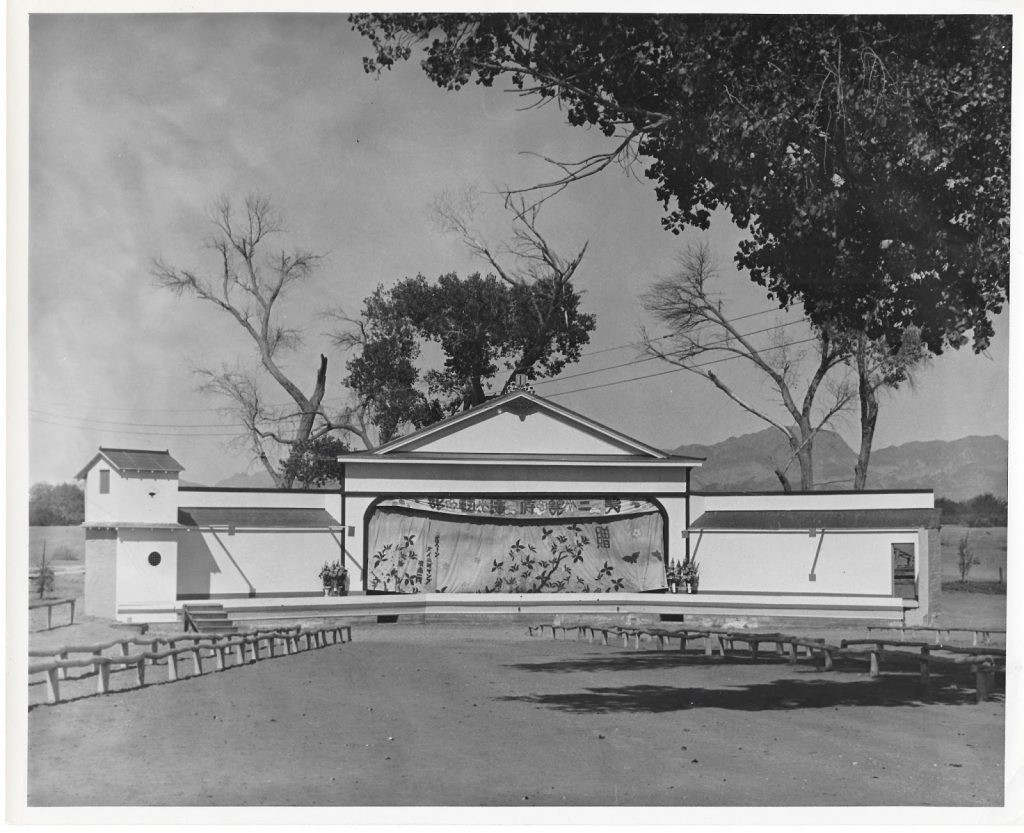

A Shibai Stage in All Three Units

Poston had an unusually robust “shibai” (Japanese dramatic performance) program that included elaborate inmate built stages in all three camps. The Unit I shibai stage had a roof and wall boards, a linoleum floor, and even a dressing room, though audience members had to bring their own chairs. There was a second smaller stage on the other side of the camp at Block 59. In Unit II, a similar stage was dubbed the “Cottonwood Bowl”; it burned down in the summer of 1945. In Unit III, the stage was in Block 310 near the swimming pool. In addition to the weekly performances that drew thousands of mostly Issei spectators, the stages were also used for movie screenings.

Japanese Language Publications

Issei published two Japanese language literary magazines, Mohabe, published by the Poston Pen Club and Poston Bungei. The latter began publication in February 1943 and went until September 1945 and included poetry and other literary work and essays on politics and history contributed by Issei and Kibei.

Camouflage Net Factory

Poston was one of three WRA camps that had a camouflage net factory. Intended for army use, the nets were made by weaving dyed burlap strips into large fishing type nets, creating a pattern that allowed the nets—and military equipment underneath them—to blend into the landscape. Having the net factories in Poston, Gila River, and Manzanar would exploit the available inmate labor, while giving inmates the opportunity to contribute to the war effort.

Poston’s short-lived net factory was marred by many problems. From the first call for workers in October 1942 as material for the factories arrived by truck, response was minimal, since there was already a labor shortage within the camp due to large numbers of workers having left to do agricultural labor outside the camp. Workers also resented the proposed $16 a month wage; since the factory work was an outside enterprise that would not benefit the people of Poston, inmates felt they should be paid wages commensurate with the going wage on the outside.

To address these competing concerns, administration officials and inmate leaders came up with a plan that would pay workers the prevailing outside wage, but that would put the bulk of that money into a trust fund that would benefit the camp population as a whole. Though inmates voted down this plan in a January 1943 election, the plans for the factory moved forward and an agreement with an outside contractor to run the factory was reached on February 13. The Unit I factory was up and running by mid-February, with factories in the other two units following. By mid-March, there were 500 workers in the three units, and they were soon producing “almost one million feet of camouflage nets daily.” Though most workers were men, a significant number were women, and in a publication put out by the net workers, a woman, Grace Kurisu, was “rated the fastest weaver in the entire factory.”

As the plants ramped up production other problems emerged. Fire Chief Joseph M. Fion noted the extreme fire hazard in the factories due to “the accumulation of burlap and lint, particularly in the cutting shed,” and threatened to shut down the plant. Many workers broke out in rashes due to the dyes used for the burlap. These issues, combined with persistently dirty latrines and continuing clashes over wages led to more workers leaving the factory. After four months, the administration decided to pull the plug on the venture in June 1942. Discussions on how to distribute the proceeds from the net factory continued for many months.

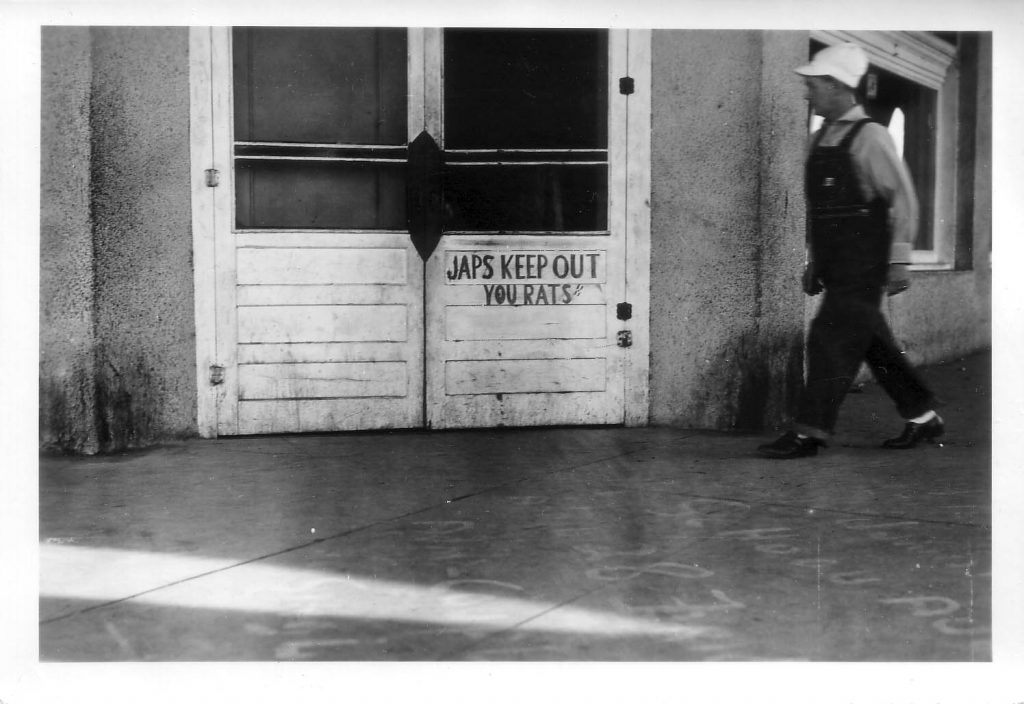

Late Run-ins with Hostile Locals

Poston was isolated even by the standards of other WRA camps, with the only nearby town being Parker, seventeen miles from Unit I. A former mining town, Bureau of Sociological Research Director Alexander Leighton described it as “a vestige of the old West with stores, saloons and rooming houses strung along covered sidewalks and a main street, and is surrounded by rubbish and decay which the desert bleaches, but does not absorb.” WRA Community Analysis Section head John Embree observed that “community sentiment, such as it is, around Poston is rather negative.” A local barbershop prominently displayed a sign reading “Japs, keep out, you rats.” Other businesses also refused to serve Japanese Americans.

Though anti-Japanese sentiment in the area eased somewhat over time, hostility remained, as indicated in two attacks on Nisei soldiers from late 1944, some two-and-a-half years after the opening of the camp. On November 9, local barber Andy Hale evicted PFC Raymond Matsuda, a wounded Nisei veteran still on crutches, from his shop. The event was much publicized and led to much community support of Matsuda. A month later, on December 18, three Nisei soldiers—Yasuo Takasaki, Kazuo Charles Sukekane, Isami Charles Tanimura—were stoned in Parker “by a gang led by a drunken deputy sheriff” while on a furlough before going overseas. This event was not widely publicized.

Murder and Escape

On September 28, 1944, twenty-four year old May Tsubouchi was found in her barrack stabbed twenty-nine times; she died in the hospital two days later. Her alleged assailant, thirty-five year old Isamu Takahashi, an ex-boyfriend who had stalked and threatened Tsubouchi in the months leading up to the assault, was seen fleeing into the desert towards Parker. Despite search parties from the camp scouring the desert as well as trains leaving Parker, Takahashi was never found.

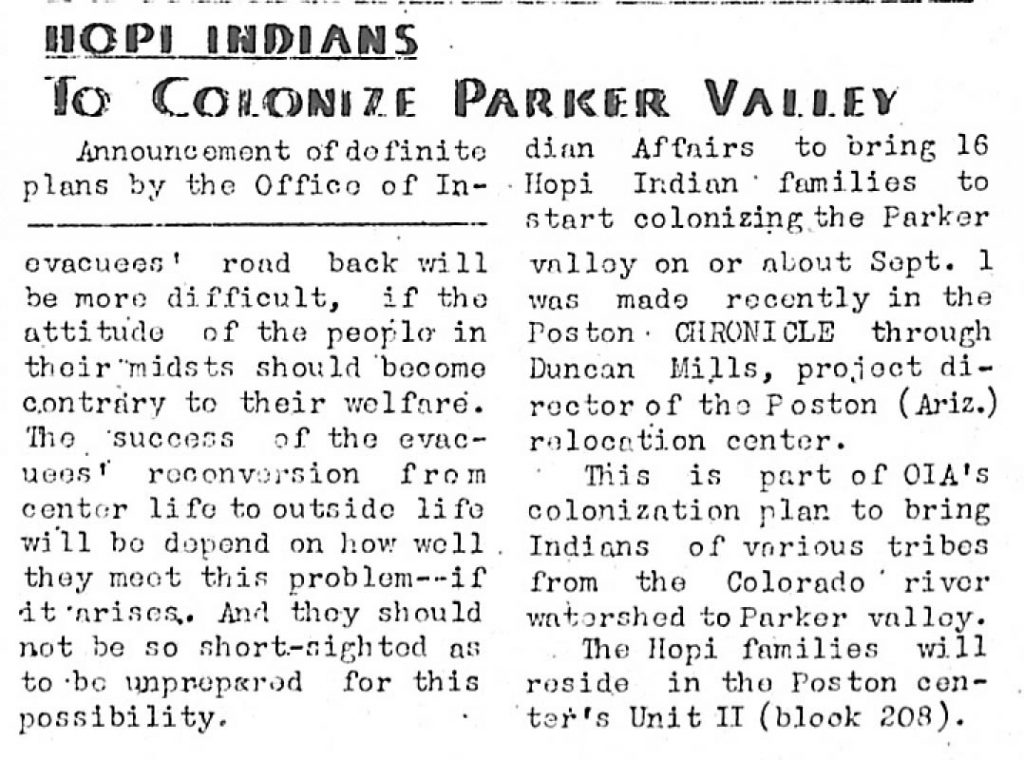

Hopi Arrival

On September 1, 1945—while the last Japanese American inmates were still inhabiting Poston—a group of sixteen Hopi families moved into Block 208 of Unit II. The remaining Japanese Americans in the block and the new arrivals apparently got along well. Upon the closing of the camp, the Hopi families got to keep barracks they had moved into. However, this influx did not foreshadow the future. The OIA’s development plans for the area that led to its administration of the Poston camp were largely abandoned. The rental fee the WRA had agreed to pay to the Colorado River Indian Tribe—who had objected to the construction of the concentration camp on their land—largely disappeared in deductions for land improvements.

—

By Densho Content Director Brian Niiya

The information presented here has been excerpted from Densho’s new and improved Sites of Shame project, coming to a device near you in 2020. Full citations will be included there, but feel free to post questions in the comments or email us at info@densho.org in the meantime!

[Header image: Original WRA caption: “Poston, Arizona. Jim Morikawa sprinkling in an attempt to settle the dust at this War Relocation Authority center for evacuees of Japanese ancestry.” May 10, 1942. Photo by Fred Clark, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]