January 30, 2019

Items called “kimono” are having a moment in the fashion world. But as guest blogger Emi Ito points out, this trend revolves around appropriation and erasure of histories that are both deeply personal and extremely political.

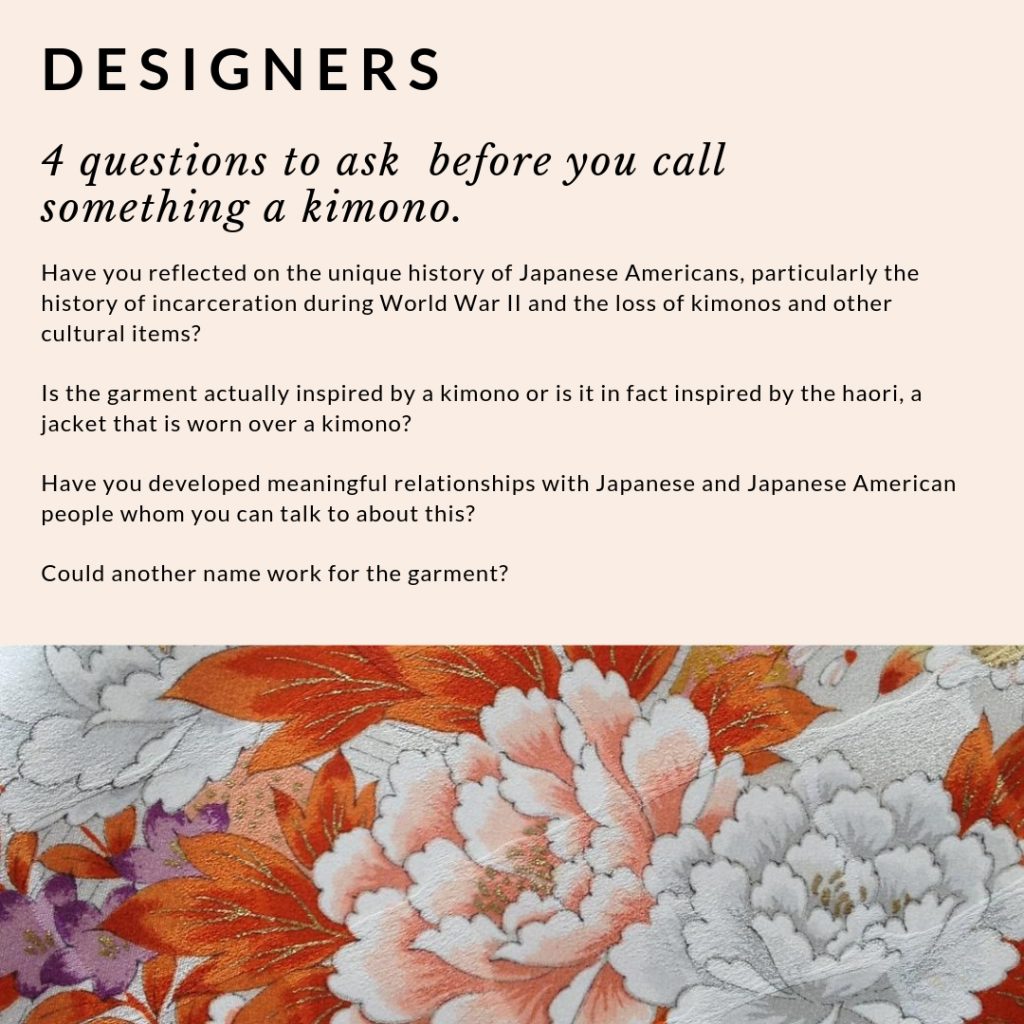

The misuse and appropriation of the kimono seems ubiquitous these days. And the term is often used to describe things that are decidedly not kimonos, including jackets, coats, sweaters, tops, and jumpsuits. Since these items hardly resemble an actual kimono, one can only surmise that the kimono label is being used to invoke “exotic” Japan as a marketing tactic.

Adding insult to injury, these garments are typically not modeled by people of Japanese heritage, but by thin white models. This trend perpetuates white standards of beauty and erases the ties these clothing items have to the actual people that “inspire” them. All of these seemingly small but meaningful choices made by fashion makers and brands capitalize on racist stereotypes, erasing Japanese American history and Japanese American people. While the intention may have been benign, the impact is not.

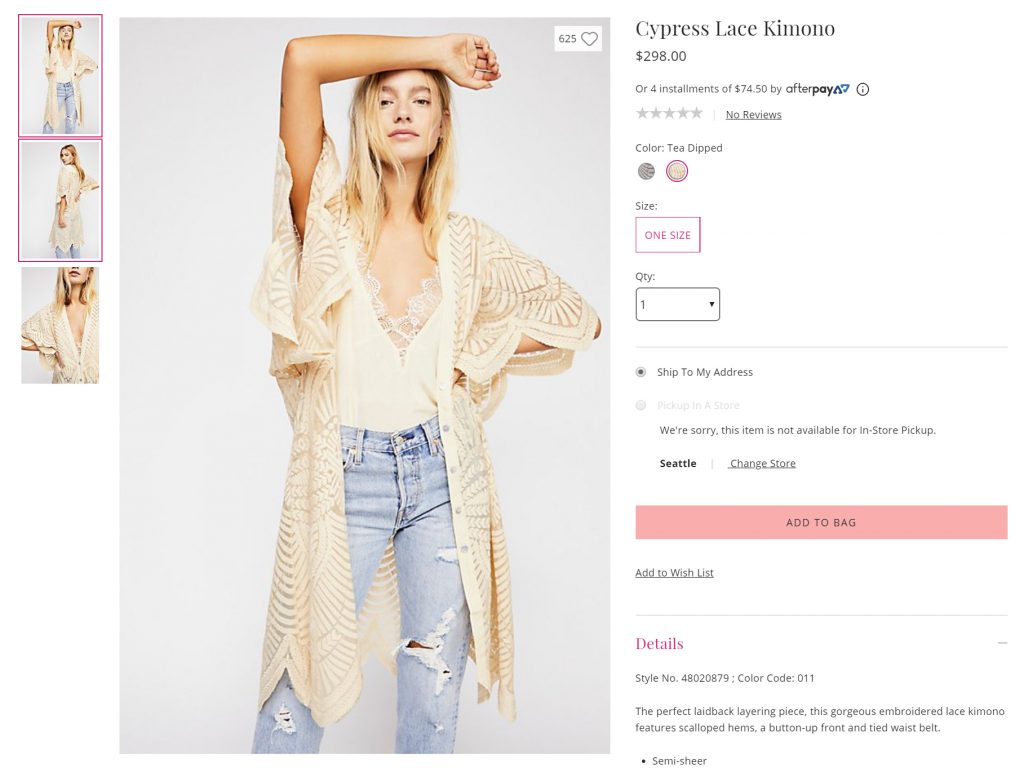

A “kimono” for sale on the Urban Outfitters website. Across the web, consumers can find jackets, coats, sweaters, tops, jumpsuits, and countless other items labeled “kimono”—they rarely bear any resemblance to an actual kimono.

Of course this Orientalist love affair with the kimono is nothing new. Since the late 1800’s, the cultural appropriation of the kimono in fashion has had a long and complicated history. Monet’s La Japonaise, The Mikado, and Katy Perry’s “geisha” look, are just a few of the many examples of the West’s fascination with all things Japanese.

But contrary to what Orientalist art and contemporary brands might have you believe, kimonos are not just clothes. They are garments worn for celebrations, sacred ceremonies, and life’s milestones. They are part of our family stories, which for some of us, are the stories of what was left behind and the people who are no longer with us.

My kimonos have been folded and tucked around the bodies of my great grandmother, grandmother, aunt, and mother. They are a part of our family’s heritage and a textured history of my matrilineal line. One day I will pass these pieces down to my own daughter so that she too can wear a garment sewn by her grandmother’s hands. These familial and cultural items have deep, even sacred significance: I wrap my ancestors around me when I wind and cinch my obi about my waist.

The author’s mother and grandmother in Hamamatsu, Japan, 1949.

The fact that I have a collection of my family’s garments is a privilege. My family does not have the historical trauma of being incarcerated during World War II because my mother immigrated to the US in the 1960s. We did not share the fate of 120,000 Japanese Americans who were charged with the “crime” of looking like the enemy and forced to take only what could be carried, then locked behind barbed wire fences for years.

My family did not have to decide between western style everyday clothes, family necessities, and precious cultural pieces like our kimono, scrolls, koto, shamisen, and lacquer pieces. The fact that some families did choose to bring kimonos with them shows what great sentimental and cultural value they hold. So many tangible pieces of family legacies were lost and even stolen because not every family was able to bring items like their traditional garments into the concentration camps. In some cases, families even burned their heirlooms out of fear that they would be seen as incriminating evidence of an imagined collusion with Japan.

Even though my family was not incarcerated, I experienced the aftermath of racism against people of Japanese heritage. I was called racist names, taunted, made to feel less than and othered. Like so many Japanese Americans, I internalized the societal messages that assimilation would be best.

Especially during the early part of WWII, those messages were explicitly taught in the camps and in resettlement programs.* English language lessons and citizenship classes, patriotic exercises, the sponsorship of boy scout troops, and required seminars on “How to Behave in the Outside World” were all part of a concerted effort to strip Japanese Americans of their cultural identities under the guise of “Americanization.” The crushing pressure of assimilation not only took away the Japanese language from many in subsequent future generations, but also weakened cultural ties, and the ability to pass down family heirlooms such as kimonos.

Rosie Maruki Kakuuchi poses in her kimono in front of barracks at Manzanar concentration camp. While many Japanese Americans had to leave cultural items like kimonos behind when they were forced into WWII concentration camps, some took the risk of bringing them along even though their luggage was severely restricted and scrutinized. Photo courtesy of the Rosie Maruki Kakuuchi Collection.

To invoke the name of a deeply significant cultural item, the kimono, without the consideration of how Japanese Americans were made to feel inferior and in many cases forced to assimilate, is hurtful and renders the history of Japanese Americans invisible.

We are witnessing a moment when history seems to be repeating itself: children and families seeking asylum are being incarcerated and separated. They too have only what they were able to carry. These stories are all too familiar to Japanese Americans. We are being told that they are the enemy we need to keep at bay by building a wall.

The stakes are high and there is much for Japanese Americans to speak out about. In light of the stark realities we are living in, cultural appropriation may feel insignificant. I would like to offer that there is room for speaking out about the large and the little injustices that hurt our hearts. I would like to offer that when we start speaking up about the little things, it gets easier to speak up about the big things.

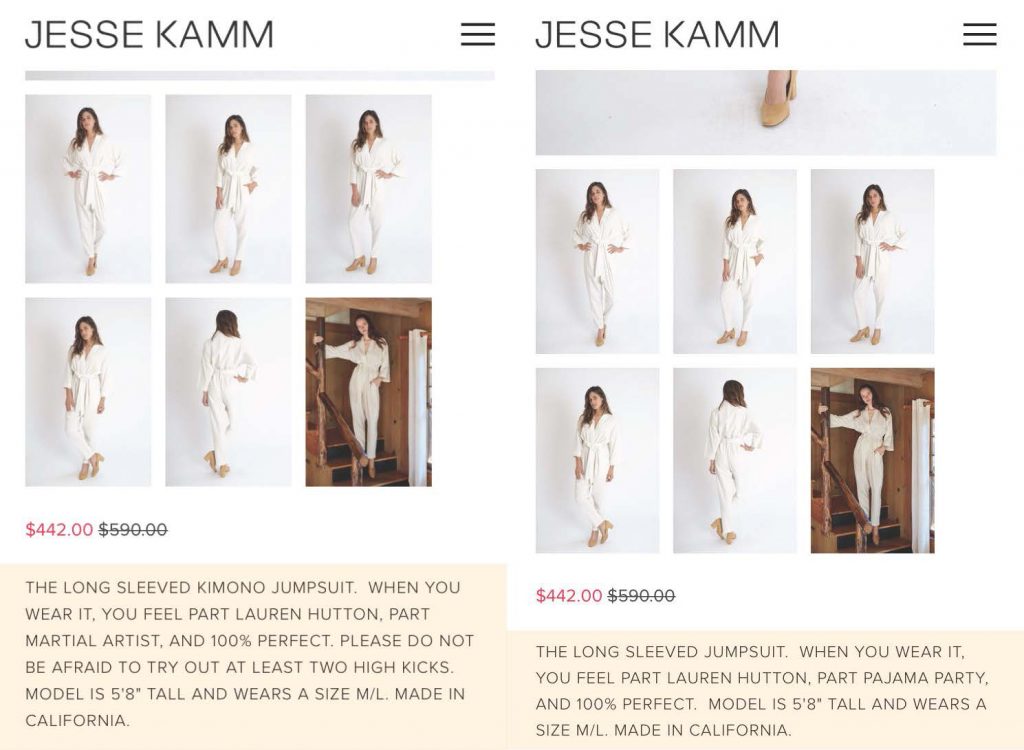

This Jesse Kamm garment was originally called a “kimono jumpsuit.” After Ito reached out to the company, they changed the name and removed other culturally insensitive language from the description.

As someone who enjoys fashion, especially the rise of ethical, sustainable, and slow fashion, where small brands feel more approachable and interested in a genuine dialogue, I worked up the courage to speak out. For garments that seem to be more inspired by the haori, I asked makers to use haori instead of kimono. I also asked some makers to change the name of their garment to duster or coat if the item did not resemble a kimono. So far several brands have made the changes including two sewing pattern makers. These tiny wins give me hope at a time when hope feels rare and far off.

I wear my kimonos to remember. When I wear them, I remember my foremothers and invoke their strength, love, and resilience. Let us be mindful of how we interact with and are inspired by cultures that are not our own. Let us truly appreciate netbet and not appropriate, by slowing down long enough to deeply consider the unique histories and the people who wear their cultural garments to communicate pride in their heritage; who wear their textured legacies wrapped around them to remember what may have been lost and what is their right to reclaim.

* While WRA administrators did eventually allow dance performances and other displays of Japanese culture in the camps, realizing it was in their interest to make a few symbolic concessions to pacify inmates, this did not undo the harm of strategic and systematic assimilation efforts.

—

Emi Ito is a mother and an elementary educator. She is a Japanese American of Mixed heritage and is part of the transracial adoptee community. She taught in Bay Area public schools for twelve years and has been an intervention teacher and coordinator for the past three. She founded and directed an arts based summer camp and after school club for youth of color who identify as multiracial, mixed heritage, and/or transracially adopted/fostered. Emi teaches rising sixth graders about Japanese American incarceration history at a Japanese American summer camp. She also served as a co-facilitator of her Union’s teachers of color organization. Slow and sustainable fashion has been a personal interest for the past few years and you can find her on Instagram @little_kotos_closet musing on social justice and toddler-proof clothes. She currently lives in the Bay Area with her partner and their very active and hilarious toddler.

[Header image: Two Nisei children wearing kimono, Seattle c. 1927-1928. Photo courtesy of the Ouchi Family Collection.]