December 16, 2025

In honor of the anniversary of the landmark decision Ex Parte Endo, legal scholar and Professor Emerita Lorraine Bannai explores the case and woman who helped bring an end to the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Bannai traces the legal and political forces surrounding the case, showing how Mitsuye Endo and her legal team challenged the government’s authority to detain citizens without cause. Endo’s story remains a vital touchstone for understanding civil liberties, wartime authority, and ongoing struggles for justice.

In 1944, the Supreme Court decided Ex Parte Endo,1 the last of its four wartime cases involving challenges to the government’s treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II. The Endo case was the only case that directly addressed the lawfulness of the incarceration. In Hirabayashi, Yasui, and Korematsu, the Court upheld the curfew on persons of Japanese ancestry and orders excluding and removing them from the West Coast, but it refused to address the lawfulness of the incarceration. While the Endo case did not address the constitutionality of the original decision to incarcerate Japanese Americans, it held that, after incarceration, the government could not continue to detain individuals once their loyalty was established. The looming decision in the Endo case put pressure on the government to close the camps when it did.2

Mitsuye Endo: The “Perfect” Plaintiff for the Case

In 1942, Mitsuye Endo was a 22-year-old clerical worker in California’s Department of Motor Vehicles in Sacramento when she and other state employees of Japanese ancestry were dismissed from their jobs.3 Then JACL President Saburo Kido recruited lawyer James Purcell to help the employees, Endo among them, but the employees had to report for removal before Purcell could file suit.

On May 15, 1942, Endo was incarcerated at the Walerga “assembly center” outside of Sacramento and then sent to Tule Lake. While at Tule Lake, she met with someone from Purcell’s office who was interviewing potential petitioners for a case.4

Purcell had decided to file a petition for writ of habeas corpus on behalf of an incarcerated state employee alleging that their detention was unlawful and had deprived them of their jobs. Through a habeas corpus proceeding, a court requires the government to produce an incarcerated person (habeas corpus means “you should have the body”) so that the court can determine whether they should be freed.5

Purcell sought the “perfect” plaintiff who would lend their name to the petition and found one in Endo.6 Although Purcell represented Endo all the way to the Supreme Court, Endo never met him.7 He filed Endo’s petition on June 12, 1942, alleging that she was a loyal U.S. citizen, that no charge had been made against her, and that she was being unlawfully held against her will.8

How Endo’s Case Moved Through the Courts

Government lawyers knew that it would be difficult to defend the indefinite detention of an entire group. For example, in July 24, 1942, War Relocation Authority (WRA) lawyer Maurice Walk wrote WRA Solicitor Philip Glick, stating his belief that “the Supreme Court will not sanction the wholesale detention of citizens” and urged that procedures to enable Japanese Americans to leave camp for the interior would be “essential in my judgment to gain judicial acceptance of our program.”

On July 20, 1942, Judge Michael K. Roche held a hearing on Endo’s petition. Purcell argued that the military could not detain citizens without a declaration of martial law, and no martial law had been declared. Government attorney Alfonso Zirpoli disagreed, arguing that the military had acted under a form of “qualified martial law.” Despite Judge Roche’s promise to rule within a few weeks, it was not until a year later, on July 3, 1943, that he issued his decision to dismiss Endo’s petition.

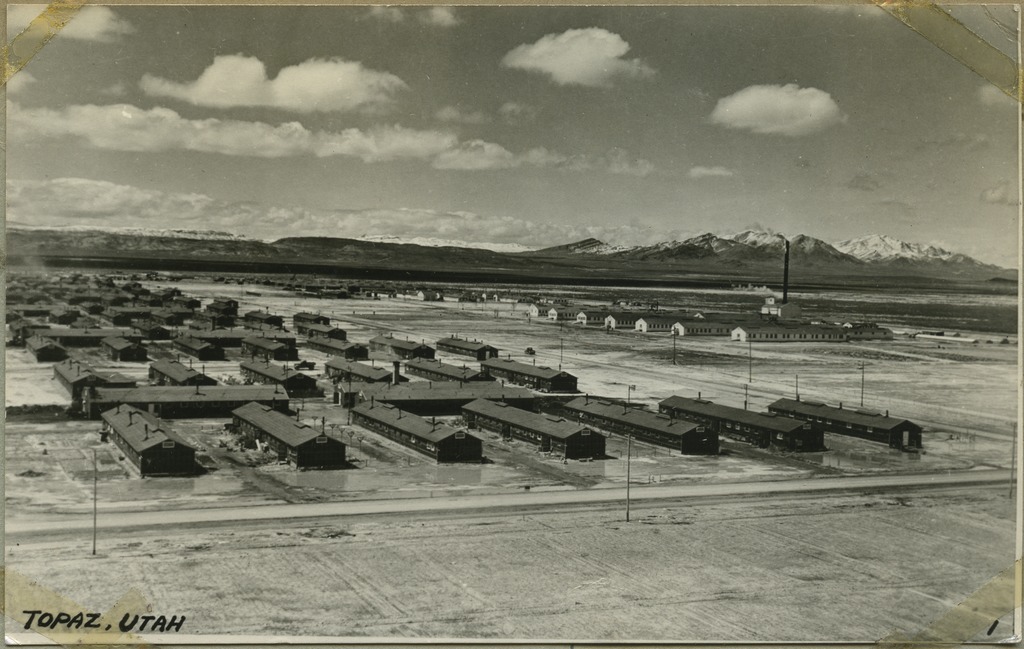

Purcell appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which certified the case directly to the U.S. Supreme Court. On May 8, 1944, the Supreme Court accepted the case for review.9 In the meantime, Endo had been transferred from Tule Lake to the concentration camp at Topaz, Utah.10

While Endo’s case was making its way through the courts, the WRA was authorized to allow individuals to leave the camps under specific conditions. In order to leave, the applicant had to clear a two-stage process. First, the applicant had to apply for leave clearance, which would be granted if the applicant established that they were not a threat to national security. Second, even if not a security threat, the applicant had to also apply for indefinite leave, which would be granted under 14 specific conditions that would ensure that they had adequate means of support at their proposed destination. In addition, no leave would be granted to a place where “community sentiment is unfavorable.” Even after leaving, the applicant had to notify the WRA of any change in address, and they could not return to the West Coast, from which they were still excluded.11

Endo applied for leave clearance, which was granted on August 16, 1943, but she did not apply for indefinite leave because leaving might result in the dismissal of her case.12 WRA solicitor Philip Glick offered her release if she agreed not to return to the West Coast. Endo refused and remained incarcerated for over another year. In a later letter, Endo wrote, “[t]he fact that I wanted to prove that we of Japanese ancestry were not guilty of any crime and that we were loyal American citizens kept me from abandoning the suit.”13

At oral argument on October 11-12, 1944, the justices were not receptive to Solicitor General Fahy’s defense of the WRA’s leave procedures. His brief did not assert any national security reasons to continue to hold Endo. Instead, it argued that the requirements for indefinite leave—that applicants have a means of support and that the community would not be hostile to them—were necessary for “a planned and orderly relocation” and intended to protect Japanese Americans by avoiding “opposition, including possible violence.”14

In conference, the justices all agreed that Endo’s petition for release should be granted. Justice William O. Douglas drafted the majority opinion and circulated it to his colleagues on November 8. However, political factors appear to have delayed the release of the opinion. On November 28, 1944, Justice Douglas complained to Chief Justice Stone that “the matter is at a standstill because officers of the government have indicated some change in detention plans.” The Court, he said, should “act promptly and not lend our aid in compounding the wrong by keeping her in unlawful confinement through our inaction any longer than necessary to reach a decision.”15 He thought the decision should be announced on December 4.

Justice Douglas was rightly concerned that internal government discussions about closing the camps might be delaying the release of the Court’s decision. While some government officials had been opposed to the incarceration from early on, more began to speak about closing the camps as some Japanese Americans were able to leave for the interior and military threats to the West Coast diminished.16 In late April 1944, Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, seeking War Department support for closing the camps, pointed out that the pending Endo case presented the looming possibility that the Court would order the camps closed, creating a danger of uncontrolled release of Japanese Americans.

As scholar Greg Robinson writes, when discussing closing the camps, FDR and his advisors sought ways to wind down the internment “on their own terms” and often “subordinated the basic rights of the internees to . . . political demands.”17 When Secretary of War Stimson raised the issue of closing the camps before the Cabinet on May 26, 1944, Attorney General Biddle noted, “War, Interior, and Justice had all agreed . . . but doubted the wisdom of doing it at this time before the election.”18 On November 10, at the first Cabinet meeting after the election, Attorney General Francis Biddle told Roosevelt that the Supreme Court would likely soon rule against the exclusion and detention in Endo. A decision was reached to end both for those whose loyalty was established.19

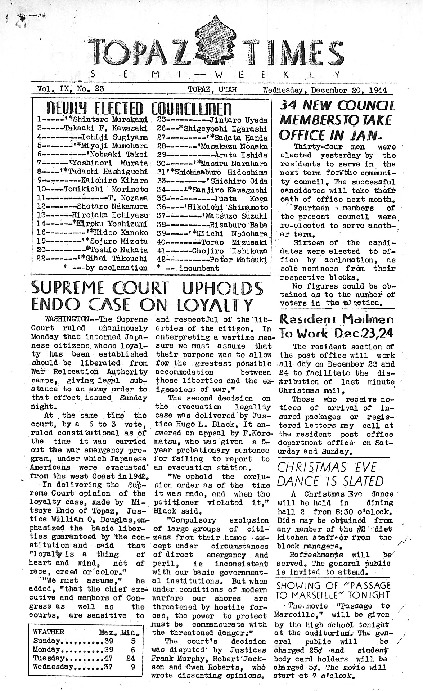

Over the next several weeks, plans were made to open the West Coast to cleared individuals,20 and on December 17, 1944, the mass exclusion orders were rescinded.

The Court issued its decision in Endo the next day, December 18, 1944. Some scholars believe that the Court purposefully delayed its announcement of its Endo decision so as not to get ahead of the government’s announcement and that Justice Felix Frankfurter tipped off the government on the date the decision would be released.21

Endo’s Release, the Supreme Court’s Decision, and Its Limits

Two-and-a-half years after Endo filed her petition, the Court issued its opinion that Endo should be freed. Justice Douglas, for the Court, explained that nothing in the language of the Executive Orders and relevant statute expressly granted the WRA the power to detain.22 While some power to detain could be implied as incident to exclusion, he stated, that implied power had to be “narrowly confined to the precise purpose of the evacuation program.” “If we assume (as we do) that the original evacuation was justified, its lawful character was derived from the fact that it was an espionage and sabotage measure.”23 The continued detention of a concededly loyal citizen, the Court concluded, no longer served the purpose of deterring espionage and sabotage and, therefore, Mitsuye Endo was “entitled to an unconditional release by the War Relocation Authority.”24

Justices Roberts and Murphy filed concurring opinions, agreeing that Endo must be freed, but criticized their colleagues for failing to address the serious constitutional issues. Justice Murphy said the detention of a person of Japanese ancestry regardless of loyalty is an “unconstitutional resort to racism inherent in the entire evacuation program.”25 Justice Owen Roberts argued that the majority’s view that neither the Executive nor Congress had authorized detention “ignore[d] [the] patent facts.” Congress, for example, had viewed reports and held hearings that related the full details of the WRA’s program.26 He stated that there was only one conclusion: that “[a]n admittedly loyal citizen has been deprived of her liberty for a period of years.”27

While the Court’s decision freed Endo and other Japanese Americans the government found to be loyal, it was limited in its reach. It did not address whether it was lawful to incarcerate Japanese Americans to begin with; in fact, it assumed that it was. Further, the Court failed to address whether Endo’s incarceration had violated any of her constitutional rights.

Endo married, moved to the Chicago area, and raised a family. During her life, she was an unsung hero in the story of the Japanese American incarceration, not receiving recognition for her courage in challenging her World War II incarceration.

Mitsuye (Endo) Tsutsumi passed away on April 14, 2006. President Biden, in awarding her the Presidential Citizens Medal posthumously on January 2, 2025, stated that her resolve “remind[s] us that we are a Nation that stands for freedom for all.”

Endnotes:

- Ex Parte Endo, 323 U.S. 283 (1944).

- Much of this article is drawn from Irons, Peter, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases. Oxford Press, 1983. University of California Press, 1993.

- Tateishi, John, And Justice For All: An Oral History of the Japanese American Detention Camps 60-61, University of Washington Press 1984.

- Id.

- Brennan Center. “Habeas Corpus Explained.”

- Endo later recalled, “I was very young, and I was very shy[.] . . . [W]hen they came and asked me about it, I said, well, can’t you have someone else do it first. . . . [T]hey said it’s for the good of everybody, and so I said, well if that’s it, I’ll go ahead and do it.” Tateishi, at 61.

- Tateishi, at 61.

- Endo, 323 U.S. at 294.

- Endo v. Eisenhower, 64 S. Ct. 1059 (1944).

- She was transferred to Topaz on September 22, 1943. Brief of Government/Respondent at 9, Ex Parte Endo (1944).

- Endo, at 292.

- Id.

- Letter from Mitsuye [Endo] Tsutsumi to Anne Saito Howden (June 5, 1989) (quoted in Tyler, Amanda L., 2017. “World War II: Suspension and Martial Law in Hawaii and Mass Detention of Japanese Americans on the Mainland” 235, in Habeas Corpus in Wartime: From the Tower of London to Guantanamo Bay. Oxford University Press).

- Brief of Government/Respondent at 63-64, Ex Parte Endo (1944).

- Irons, Justice at War at 344 (quoting Douglas to Stone, Dec. 8, 1944, Box 74, Folder—Correspondence-Douglas 1944, Stone Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Wash. DC.)

- For a discussion of internal debates among government officials about closing the camps, see Greg Robinson, By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans, Harvard University Press 183-230, 2001.

- Id. at 205-06.

- Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied 228. 1997 University of Washington Press.

- Id. at 233.

- Id. at 235.

- Irons, Justice at War at 345 (citing interview with scholar Roger Daniels).

- Endo, 323 U.S. at 300.

- Id. at 301-02.

- Id. at 304.

- Endo, 323 U.S. at 307 (Murphy, J. concurring).

- Id. at 308-09 (Roberts, J. concurring).

- Id. at 310.

Learn more:

Ex Parte Endo, 323 U.S. 283 (1944).

Irons, Peter. Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases. Oxford University Press, 1983. University of California Press, 1993.

Bangarth, Stephanie. 2008. Voices Raised in Protest: Defending Citizens of Japanese Ancestry in North America, 1942–49. UBC Press.

Gudridge, Patrick O. 2003. “Remembering Endo?” Harvard Law Review 116: 1933-69.

Juhn, Mina. 2023. “’Concededly Loyal’: Mitsuye Endo and the Continuing Significance of Ex Parte Endo,” 27 Asian Pac. Am. L.J. 99.Yamamoto, Eric, Lorraine Bannai, and Margaret Chon. Race, Rights, and National Security: Law and the Japanese American Incarceration 170-84, 3d edition. Wolters Kluwer 2021.

—

Lorraine K. Bannai is Professor Emerita at Seattle University School of Law, where she worked with the Fred T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality. While in private practice, she served on the legal team that successfully overturned Fred Korematsu’s World War II conviction for violating removal orders issued against Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Professor Bannai has written and spoken widely on the wartime Japanese American incarceration and its present-day relevance. Her books include the co-authored Race, Rights, and National Security: Law and the Japanese American Incarceration, and her biography of Fred Korematsu, Enduring Conviction: Fred Korematsu and His Quest for Justice. She is also an author for our Densho Encyclopedia.