June 23, 2025

Manzanar is perhaps the most well-known of the ten War Relocation Authority concentration camps where Japanese Americans were incarcerated during WWII, thanks to popular media portrayals from Farewell to Manzanar to Teen Wolf, its distinction as the first of the camps to be recognized as a unit of the National Park Service, and other highlights. But even eight decades later, there are still more stories to uncover.

For over a year, we’ve been working on a project to update core articles and add new content to the Densho Encyclopedia. The first phase has focused on content with California connections and includes several new articles that explore lesser-known chapters of Manzanar’s history. All of the new articles will be published soon, but in the meantime, we’ve compiled a sneak peek at a few of these people, places, and organizations connected to the Manzanar concentration camp.

This project was supported, in part, by funding provided by the California Civil Liberties Public Education Program, administered by the California State Library. It was also assisted by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service.

Anti-Axis Committee

The Anti-Axis Committee (AAC) was an organization formed in Los Angeles in the immediate aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor to coordinate Japanese American community efforts to support the war effort. Though short-lived, the AAC became notorious for the degree to which it cooperated with government agencies, which led to its core members being vilified and sometimes physically attacked in Manzanar and other concentration camps.

Formed on December 7, 1941, the AAC became a unit of the Japanese American Citizens League‘s Southern District Council and was led initially by businessman and JACL leader Fred Tayama. Its stated objectives were “to cooperate with all national, state and local government agencies in their program in this emergency; coordinate citizen and alien activities; [and] get fair treatment for loyal Americans.”

The AAC was active over the next couple of weeks, paying visits to Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron and other local and federal officials to pledge their cooperation, providing names and addresses of “possible subversives” to the FBI, and making professions of loyalty in mainstream Los Angeles newspapers. There was almost immediate blowback to the AAC’s statements and actions, and Tayama, Slocum, and others associated with the AAC became targets of inmate rage at Manzanar. The beating of Tayama and its aftermath at Manzanar led to large scale revolt that helped change the course of the incarceration.

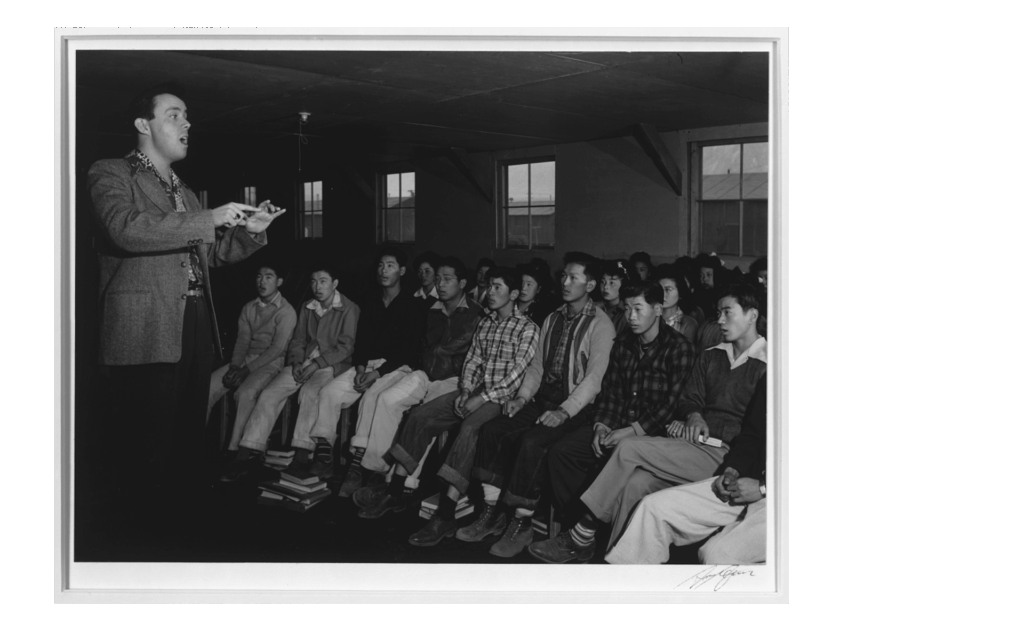

Lou Frizzell

Lou Frizzell was a popular young music and drama teacher at Manzanar who went on to a career as a character actor on stage and screen after the war.

Frizzell’s stint as a music and drama teacher at the high school and adult school in Manzanar was his first job after graduating from UCLA. Upon his arrival in September 1942, he immersed himself in the life of the camp, directed an a cappella choir and band/orchestra that performed at numerous camp functions, and served as a judge in talent contests, as a board member of the Manzanar YMCA, and as an accompanist to various solo performers — including Mary Kageyama, the “Songbird of Manzanar.”

Frizzell was remembered warmly by many of his students and kept in touch with some of them. Sumiko Yamauchi recalls him coming to visit former Manzanar incarcerees living in Seabrook Farms, New Jersey after the war, while playing in a Broadway show. She called him “one of us,” someone who “was there at the baseball games, he was there at the dances, and he not only was there at the dance, he used to dance with the kids.” Marian Uyematsu Naito recalled visiting him with other former incarcerees at his home in Eagle Rock. “So there was a difference between a music teacher and someone who really loved us,” recalled Bruce Kaji. “He got young people to do stuff they never would have done had they lived outside of camp.”

Jim Matsuoka

Councilor, educator, and activist Jim Matsuoka was a key figure in the commemoration of Manzanar as a historic site. Born Haruyuki Matsuoka on July 27, 1935, he grew up in Little Tokyo and, like many Nisei, took on a Western name, “Jim,” while in elementary school. The Matsuokas were removed to Manzanar in March 1942 and remained nearly for the duration, living in Block 11. Upon leaving Manzanar, the family lived in the Los Cerritos trailer camp in Long Beach, which Matsuoka described as “barely fit for human habitation,” before eventually moving back to Los Angeles.

In the late 1960s, Matsuoka began to get involved in the Japanese American and Asian American community. Disturbed by the eviction of indigent Issei residents of old buildings that were to be torn down to make room for new development, he became active with community groups like the Little Tokyo Anti-Eviction Task Force and Little Tokyo People’s Rights Organization. Like many other redevelopment activists, Matsuoka was also a vocal supporter of redress, becoming one of the founders of the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations (NCRR).

Much of Matsuoka’s advocacy focused on ensuring that Manzanar’s history as an American concentration camp would never be forgotten. He attended the first Manzanar Pilgrimage in December 1969, where he made an oft quoted speech that criticized Japanese American passivity and silence after the war: “The only people who ever came out of this camp were people without souls, the ‘Quiet Americans’… When people ask me, how many people are buried in the cemetery? I say, ‘A whole generation is buried here.’” He later became a member of the Manzanar Committee, which planned subsequent pilgrimages, and, along with Rex Takahashi, drafted the wording on a plaque put up at the Manzanar site that called it a “concentration camp” and that attributed the incarceration of Japanese Americans to “war hysteria, racism, and economic exploitation.” Though controversial at the time, that text was eventually adopted over the objections of the California Historical Landmarks Advisory Committee and remains intact to this day.

Sawtelle/West Los Angeles

The historic Japanese American community of Sawtelle in West Los Angeles was an enclave for Japanese American gardeners who tended to the homes of the exclusive neighborhoods surrounding it — both before and after many of them were incarcerated at Manzanar.

By the eve of World War II, there were over 1,000 Nikkei in Sawtelle, with about half of employed Japanese American men in the area working as gardeners. While some were among the early “volunteers” who went to Manzanar in late March and early April, the bulk of Sawtelle area Japanese Americans were taken to Manzanar on April 27, 1942 under Exclusion Order No. 8. Many left behind belongings at the West Los Angeles Japanese Methodist Church, “with furniture piled almost to the ceiling.” Pastor Herbert Nicholson became a legendary figure for making dozens of trips to Manzanar and other camps to bring stored furniture, pets, and other belongings to incarcerated Japanese Americans.

Relatively speaking, the many gardeners in Sawtelle faired better than other Japanese Americans, as many owned homes and were able to store their tools and equipment in their garages, while renting out their homes. Nursery owners, on the other hand, had a particularly difficult time, given their large inventories that they had to sell off at fire sale type prices. According to the Manzanar Community Analysis Section study authored by a local Kibei, some leased their land to “fellow Mexican workers on a share basis, and some sold them to the Caucasian nurserymen.”

Landscape gardening played an even larger role in the community after the war than before. By December 1946, there were 1,061 Japanese Americans once again living in Sawtelle. More than three-quarters of the employed Nikkei men among them were gardeners — influenced in large part by a postwar boom in demand for “Japanese” gardeners. As many as ten boarding houses sprang up to house new gardeners and others. The Kobayakawa Boarding House, established in the 1920s but expanded after the war to hold up to sixty tenants, helped new gardeners sharpen their skills and became known as a “gardening college” into the 1970s.

Manzanar Visual Education Museum

The Visual Education Museum (VEM) at Manzanar served as a popular natural history and art museum, a zoo and recreational site, and resource center for educators in its two-and-a-half years of existence.

The museum’s founder and director was Kiyotsugu “Bill” Tsuchiya, who had worked for eccentric millionaire George Harding Jr. as the live-in curator of Harding’s collection of arms and armor, giving regular tours that reportedly included Al Capone. After Harding’s death in 1939, Tsuchiya and his wife Chie moved to the Los Angeles area, where they ran a nursery. With the forced expulsion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast in 1942, the Tsuchiya family—which now included a toddler daughter, Kieko—ended up at Manzanar.

Given his unique background, Tsuchiya was tapped by education supervisor Genevieve Carter to organize and collect visual resources for use in the Manzanar’s schools. Tsuchiya and his staff—which included noted artist Kango Takamura and famed photographer Toyo Miyatake—quickly built a collection of thousands of photographs, illustrations, maps, and other visual aids, as well as samples of the flora and fauna of the surrounding area. In a report on the early history of the VEM, Tsuchiya noted the poor conditions in the barrack that saw the owl, sparrow and snake die of cold, while the “mouse escaped and ate up our collection of insects.” Undaunted—and with ambitions to be more than an educational resource center—Tsuchiya and staff opened what was now called the Visual Education Museum (VEM) to the public on December 5, 1942.

The VEM proved to be a popular destination for incarcerees and even some visitors from outside the camp. Exhibitions included everything from the natural and human history of the region, to arts and crafts by the incarcerees, to general interest topics such Hollywood movie studios or transportation. There was also a Visual Aids Room with resources for teachers, such as a phonograph, projector, and educational aids with pictures, slides, and maps. While animals were initially kept at the museum, a subsequent ban led to museum staff forming what became a zoo at the edge of the camp that included hawks, owls, roadrunners, rabbits, chipmunks, and a turtle.

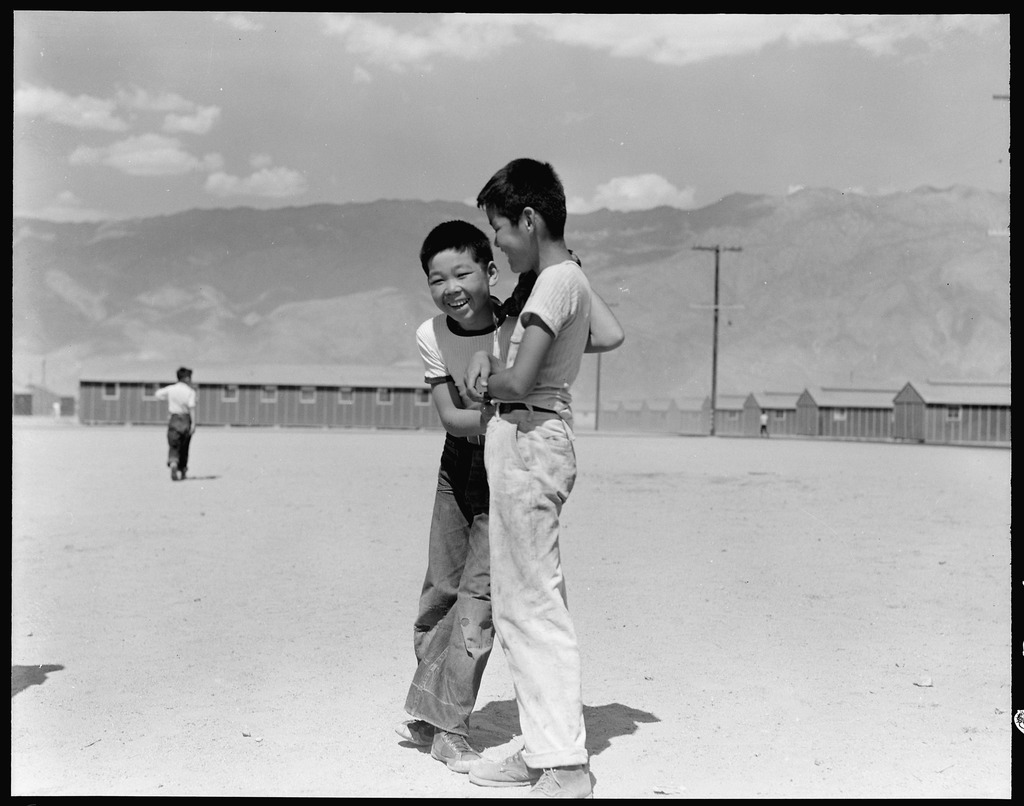

[Header: Young Japanese Americans playing in Manzanar. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]