December 6, 2024

Dr. Koji Lau-Ozawa is a postdoctoral fellow at UCLA and archaeologist studying the Japanese diaspora and intersections of Asian American and Indigenous histories. Much of his research focuses on the Gila River Incarceration Camp where his family was confined. He has spent the past two years working with a dedicated group of students to memorialize the long unacknowledged history of Japanese American incarceration at the Tulare Assembly Center. He shares the origins of that project, his own connections to Tulare, and how to join the efforts to bring the Tulare memorial to life.

In 2017, I drove down Highway 99, hoping to stop at all of the temporary detention facilities, known euphemistically as “assembly centers,” which held people who were later incarcerated at Gila River. My family was confined at Gila River, and that camp was the focus of my dissertation research. I was curious about what remnants were left of the detention centers and if they had any kinds of memorialization. Driving from San Francisco, I first stopped at Tanforan and noted the small rock garden which was the only marker there, before the more recently opened memorial. As I left the Bay Area on that hot August week, I made my way through Stockton, Turlock, Fresno, Pinedale, Merced, and Tulare, and eventually finished at Santa Anita Race Track in Arcadia. At most of these sites, there were plaques or even whole courtyards memorializing their use at detention facilities. The commemoration ranged in its comprehensiveness and style, but one could visit these fairgrounds, racetracks, and plazas and know that something had happened there.

The exception was Tulare. Of the 15 detention facilities in California, Tulare was the only one with no plaque, marker, or memorial of any kind. Still operating as the site of the county fairgrounds, a visitor to the site would be none-the wiser about its use during WWII. A class of local high school students, however, is working to change that. At Mission Oak High School in Tulare, Michaelpaul Mendoza taught a Cultural History course between 2016 and 2023. In it, he noted the local connection that Tulare had to Japanese American incarceration. His students were shocked by this knowledge, as most had grown up in Tulare, attended the county fair regularly, and had never known.

Over the eight years, the students of the class, and students from successive years, have worked to learn more about the history of the Tulare Detention Center, raise awareness of it in their local community, and create a memorial at the site. The community has embraced this project, as has the Tulare County Fairgrounds board, approving a proposal to construct a memorial at the site. With that approval, in 2022, the students pivoted to reach out to the Japanese American community to understand what community members want to see in a memorial. In 2022 they invited survivors and descendants to visit the fairgrounds and participate in a panel hosted by the Tulare Historical Museum. In 2023 they participated in a virtual panel as part of the Tadaima! A Community Virtual Pilgrimage program that year. They hosted another meeting in the summer of 2024. However, reaching out to survivors and descendants has been no easy task, in part due to the geographic distribution of the detention facilities’ prisoners.

From Far and Wide

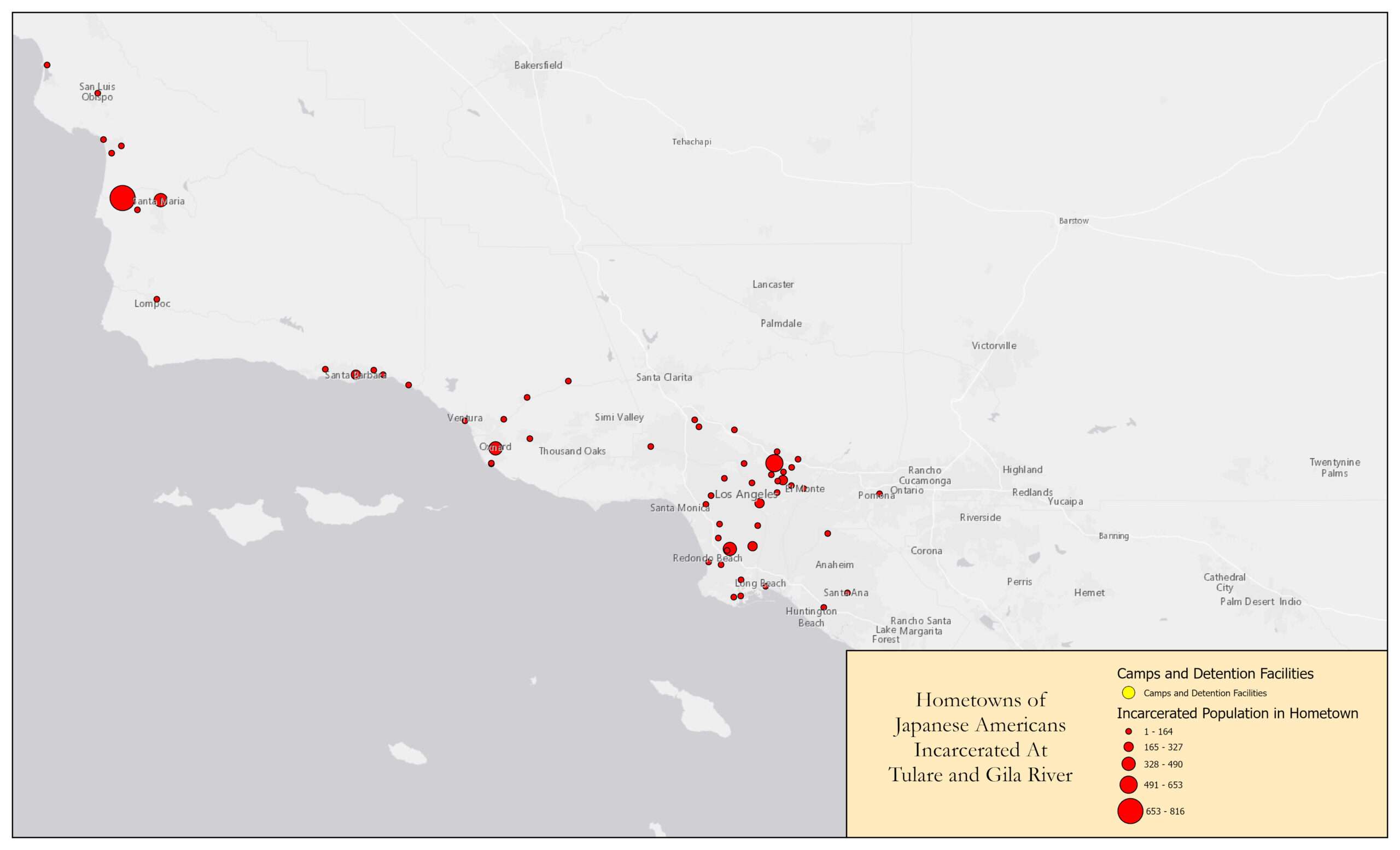

The Tulare Temporary Detention Facility opened on April 20, 1942 and operated for four and a half months, closing on September 4th of the same year. A total of just over 5,000 Japanese Americans were confined there, including my grandparents, great-grandparents, and numerous aunts and uncles. According to the Final Report issued by General DeWitt, people from “Evacuation Zones” 12 (Ventura), 13 (Santa Barbara), 14 (San Luis Obispo), 29 (Gardena), 30 (Compton), and 54 (Pasadena) were sent to Tulare. The map below shows an approximation of the hometowns of those who were confined at Tulare.

Memories of Pain

One of the people incarcerated at Tulare was Hatsuye Egami, an Issei woman and prolific writer. Egami kept a diary of her time leading up to and during her incarceration, detailing her time at the Tulare detention facility. She wrote both of the difficulties of life there as well as the resiliency of Issei in the camp in particular. Poor infrastructure, substandard food, dust and dirt covering everything. Her account of Tulare highlights the rushed nature of these detention facilities and the harsh new realities facing Japanese Americans. In one particularly striking passage, Egami writes of the latrines:

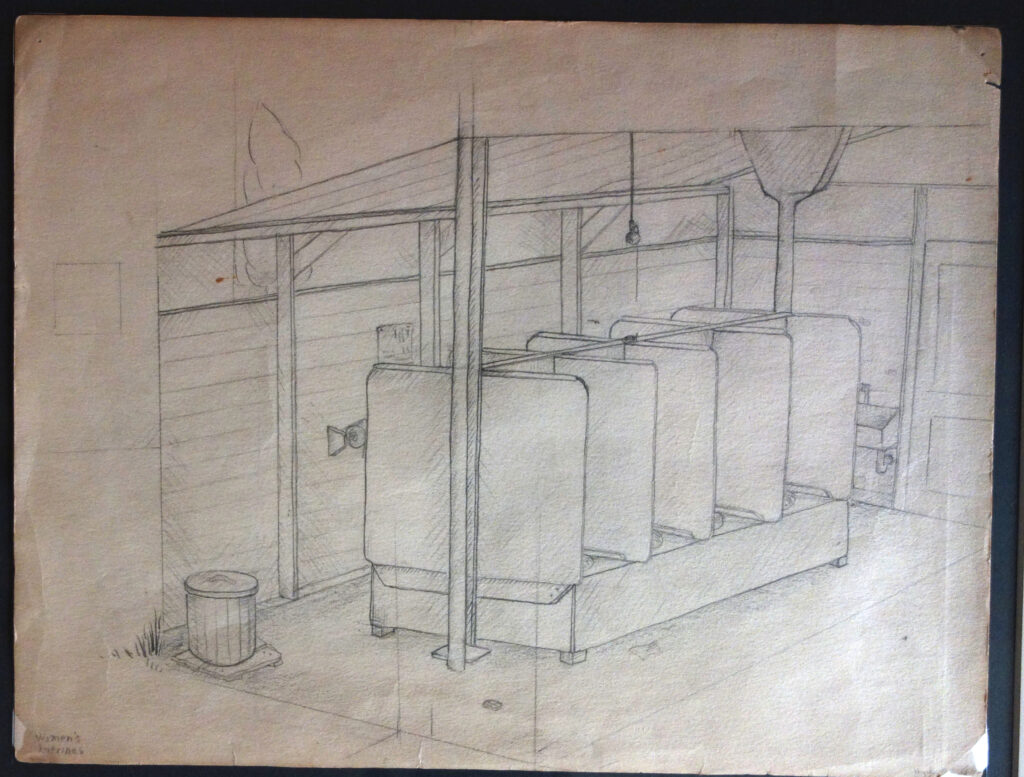

As soon as we enter, my daughters shriek. I indeed felt sorry for my daughters. In the latrine the cloak of modesty must be shed and we must return to the state of nakedness in which we were born. Polished civilized taste and fine sensitivities seem to have become worthless here.

Egami’s description of the latrines matched my grandmother’s stories when she spoke to me about Tulare. Her sketches appear in the published version of Egami’s diary, and as one can see in the image below, the latrines lacked meaningful dividers, exposing people at some of their most intimate moments. My grandmother remembered this as particularly shameful and embarrassing, stripping her of any dignity after her forced removal from Pasadena.

Seeking Guidance

The memorial project at the Tulare County Fairgrounds is working to honor the pain and trauma of the Japanese American community that was confined there. Currently, the plans for the memorial include a bronze bas-relief designed by local artist Sam Peña, who has designed hundreds of bas-relief sculptures across the country, including many in monuments in Washington, DC. The memorial plans will also include a wall of names of all Japanese Americans incarcerated at Tulare and five storyboards to describe the history of incarceration and Tualre’s role in that process.

It is with these storyboards that the memorial committee is now seeking input. Many of the memorials at detention facilities have storyboards to inform the public on the history of Japanese American incarceration. Including them at the Tulare memorial is especially important given the previous lack of awareness of the site’s history. At the same time, it is important to the students that the voices and perspectives of the Japanese American community guide what goes into those storyboards. The community must be able to lead in telling its history. In this spirit, they are collecting input into these storyboards through a google survey, available here. They will discuss this input in a public meeting in January 2025.

I have now worked with these students and their teacher for two years and am constantly in awe of their dedication to this project. To see young people dedicate their time, including giving up evenings after school and weekends to prepare for events, talk to community organizations, and meet with survivors and descendants is truly inspiring. My colleague Barre Fong and I are currently producing a documentary on these student’s efforts, supported by the California State Library’s Civil Liberties Public Education Program. We hope that not only will their story highlight the history of Japanese American incarceration and the temporary detention facilities, but inspire young people to know that they can make a difference in the world. At this current moment, when the threats of deportation camps, mass round-ups and the elimination of civil liberties are at an all time high, it is more important than ever that we confront our history as a country, and empower those who strive to make the world a better place.

—

Find more of Dr. Lau-Ozawa’s work here, or contact him at khozawa2@ucla.edu.

Complete the survey by December 15, 2024 to provide feedback on the Tulare Memorial storyboards.