July 13, 2023

Erin Shigaki, Seattle-based artist and Densho’s inaugural Community Curator, caught up with photographer Dean Terasaki to learn how he’s turned his lens toward an 80 year old family mystery.

In May of this year, I traveled to the Jerome/Rohwer Pilgrimage. As a fellow pilgrimage organizer, I was there to support my friends at Japanese American Memorial Pilgrimages, and to gain a deeper understanding of this pair of concentration camps in rural Arkansas. I fortunately crossed paths with photographer Dean Terasaki, whose family ran the T.K. Pharmacy and sent medicine and other supplies to Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII. He had come on the pilgrimage seeking guidance to tell their tales, and carried with him a beautiful and simply bound book containing selections of his photo montage work examining letters sent to T.K. Pharmacy from the camps.

The following is an excerpt of our conversation about Dean’s work, personal memory, and how we—eight decades later—figure into the mysteries of these rediscovered letters.

Erin Shigaki: Dean, tell me a little about yourself as a Japanese American—what generation you are, any camp affiliation or connection, and anything else you might want to share about your relationship to Nikkei identity.

Dean Terasaki: I am Sansei. My father was a Denver native. My mom was born on the farm near North Platte, Nebraska. Because their families lived outside of the Western Military Region, they were not incarcerated. Reverend Hiram Kano, the rector of Mom’s church, was arrested on Sunday, December 7, 1945, and subsequently incarcerated. Dad was initially registered for the draft as an enemy alien, even though he didn’t speak Japanese. He was eventually drafted, and served in combat in the 100th Battalion / 442nd RCT. My parents’ social circle was mostly JA families that they had grown up with as well as lots of aunts, uncles and cousins. The JA community was centered at a Buddhist temple and at Simpson Methodist church. Mom insisted on going to Denver’s largest Episcopal church—I believe because one of the gentry there had suggested she go to one closer to our home. Difference, ethnicity and race all pop up— sometimes at the oddest moments. The counterculture scene in the early 70’s and later my love of punk were manifestations of the sort of general anger I felt toward mainstream culture and the outsider status I had always felt. I have often said that my childhood discovery of a box of my father’s WWII photographs and military medals sparked my interest in photography and its connection to memory.

ES: Your uncles ran T.K. Pharmacy in Denver, CO. Can you tell us about its history?

DT: I believe this story starts with my grandpa, Masaemon Terasaki, who managed an import business—the S. Ban Company. Although that business failed during the Great Depression, it seems apparent that the family had a belief that a family-owned business could survive with enough hard work. I don’t know where T.K. Pharmacy’s initial financing came from. Dr. Thomas Kobayashi, who was married to Dad’s oldest sister, seems to have been the financial leader, but there wasn’t agreement in the family about that. In any case, Dr. Kobayashi’s medical practice was upstairs and my Uncle Yutaka “Tak” Terasaki ran the pharmacy on the first floor.

The pharmacy and medical practice were located at the edge of the historical JA neighborhood on the northern edge of downtown Denver. After the war, Dad worked for his brother, Tak. Mom worked for Uncle Tommy upstairs as a nursing assistant. That’s how Mom and Dad met. I remember visiting Dad at T.K.’s before he opened his own drug store. Uncle Tak ran that pharmacy until he moved to a new location in the middle of the Black community northeast of downtown Denver. The original T.K. Pharmacy building is still standing and now is a clothing store.

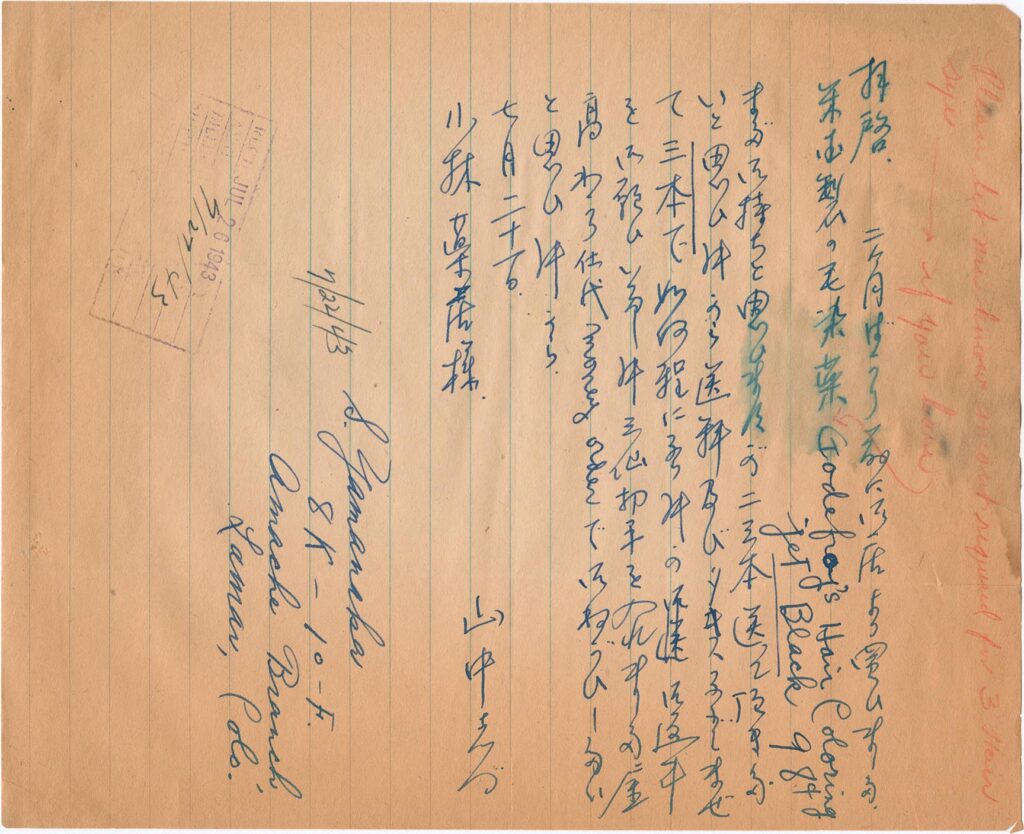

ES: An incredible stash of documents was found hidden within the walls of your family’s former building in 2012. These pieces of paper were from the 1940s and included letters and orders from Japanese Americans incarcerated in WRA concentration camps including Topaz, Tule Lake, Amache, Gila River, and Heart Mountain. Requests range from sake to art supplies to medicine, all of which were hard to come by in the camps. What are some of the discoveries that have come from this finding?

DT: I did learn a few things, but the letters are also a source of mystery. The requests for black hair dye and sake give a sense that life goes on. In my mind, the hair dye requests are stories of horrible stress over losing everything and not knowing when or if the incarceration would end. But I believe those requests are also powerful signifiers of the community’s desire to “save face” by keeping one’s dignity and the human desire to bring forth beauty, particularly in the face of adversity. Some letters asking for sake mention upcoming weddings or celebrations—again, I believe a sign of strength and solidarity among the incarcerated. Asking for art supplies—shikata ga nai, right?

I find myself really intrigued by the mystery surrounding the letters. Why were they hidden? Why hadn’t either uncle ever said anything about the letters? I have heard anecdotally that the usual mail orders from Wards and Sears to the incarcerated JA community were unreliable. Was that racism? My father was always looking to do business with other Japanese Americans. Was there a fundamental mistrust that he never spoke about?

ES: Let’s talk about your work as a photographer. How have you incorporated the T.K. Pharmacy archives into your work?

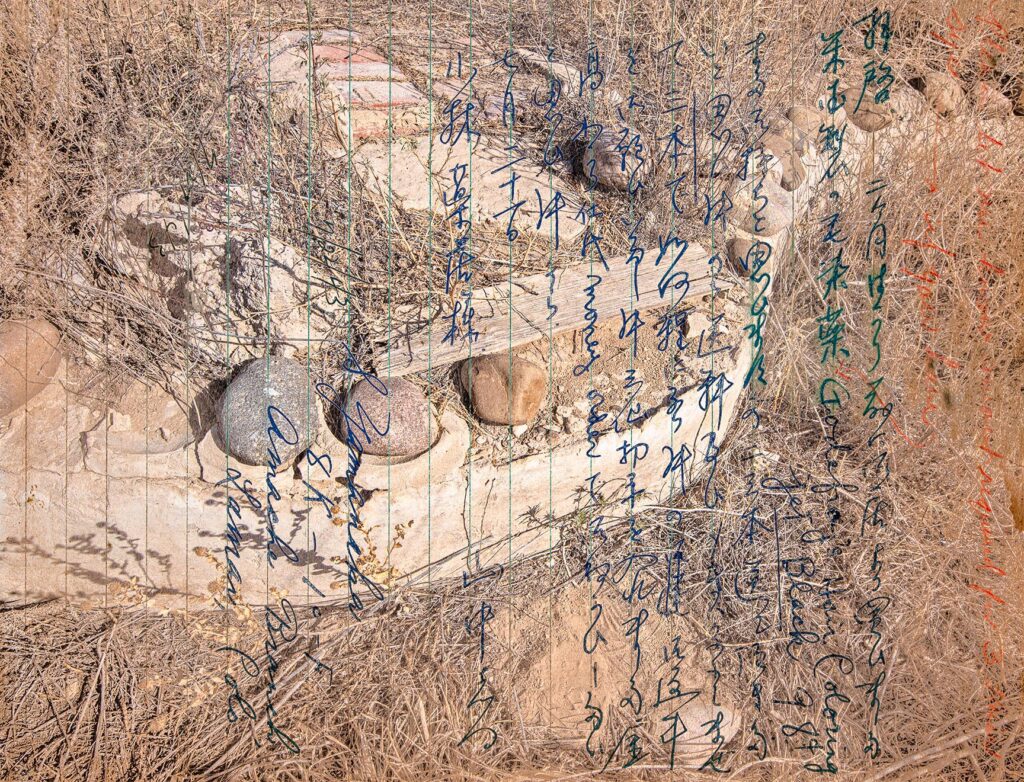

DT: I’ve made montages since graduate school—which was before Photoshop, I might add. I believe it’s my responsibility as a storyteller to bring some clarity to the stuff I see. A photograph always holds more than simply its subjects and the spaces around them. The way that we see any photograph is always imbued with our own sensibilities, memories and emotions. Montage gives me a way to direct an audience to those half-remembered experiences that color the way I see a particular subject.

The T.K. Pharmacy letters are precious to me because they represent my family’s connection to the JA community’s trauma. Those letters hold the mystery, confusion, fear and powerful strength that I experience when I visit a site of incarceration. I believe it’s important to share that experience by bringing the letters back to the sites where they were written. I hope to make that experience compelling so that the trauma never happens again. In this current moment, where large numbers of people want to erase uncomfortable racial truths, I believe this is more important than ever.

—

Erin Shigaki (she/they) is a yonsei (fourth-generation) Japanese American born and raised in Seattle, WA. She creates murals and installations that are community-based and focused on BIPOC experiences, often the WWII incarceration of her family and Japanese American community. She is passionate about highlighting similarities between that history and systemic injustices communities of color continue to face. She is keen to understand intergenerational trauma and to explore the emergence of beauty and intimacy despite unspeakably harsh circumstances. And she believes that wielding art and activism to tell these stories can educate, redress, and incrementally heal.

Erin is also a community activist and helps run an annual pilgrimage to Minidoka, the American concentration camp where her family was incarcerated. She is active with Tsuru for Solidarity, a nonviolent, direct action abolitionist project of Japanese American social justice advocates. She also serves on the board of Look Listen + Learn, a public access television show that inspires radical Black joy and advances early learning in young children of color. All of this work is fundamental to her artistic practice.

Dean K. Terasaki is a sansei. As a child, he found a box filled with photographs from his father’s service in the 442nd. That box was the seed of his interest in the relationship between photography and memory. As a young man, Dean hopped freight trains, drove taxicabs, and realized that he carried a camera everywhere. He earned a BFA from the University of Colorado in 1978 and a MFA in photography from Arizona State University in 1985. After a brief move to New York City, Dean returned to Phoenix where, for 33 years, he taught photography at Arizona’s Glendale Community College. Now retired, he lives in Phoenix with his wife, Teri, and their dog, and continues to make images.

[Header: A photomontage created by Dean K. Terasaki from two images. One is a detail of the Poston Concentration Camp Monument near Parker, Arizona. The other is a request for inkstone, ink and brushes in a letter sent to T.K. Pharmacy by S. Masukane. Courtesy of Dean K. Terasaki.]