January 18, 2023

In an excerpt from her foreword to a new re-release of Yoshiko Uchida’s Picture Bride, Elena Tajma Creef shines a light on the unsung history of the women who inspired the classic novel and its long-lasting impact on Asian American literature.

Yoshiko Uchida’s legacy as one of the most prolific Japanese American writers of the twentieth century remains unmatched. The daughter of first generation Issei immigrant parents, Uchida was born in 1921 in Alameda, California, and together with her family was caught up in the tragic World War II removal and relocation of Japanese Americans to Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, California, and later to the Topaz concentration camp in Utah—the same destinations that form the backdrop for the final act of her 1987 novel Picture Bride.

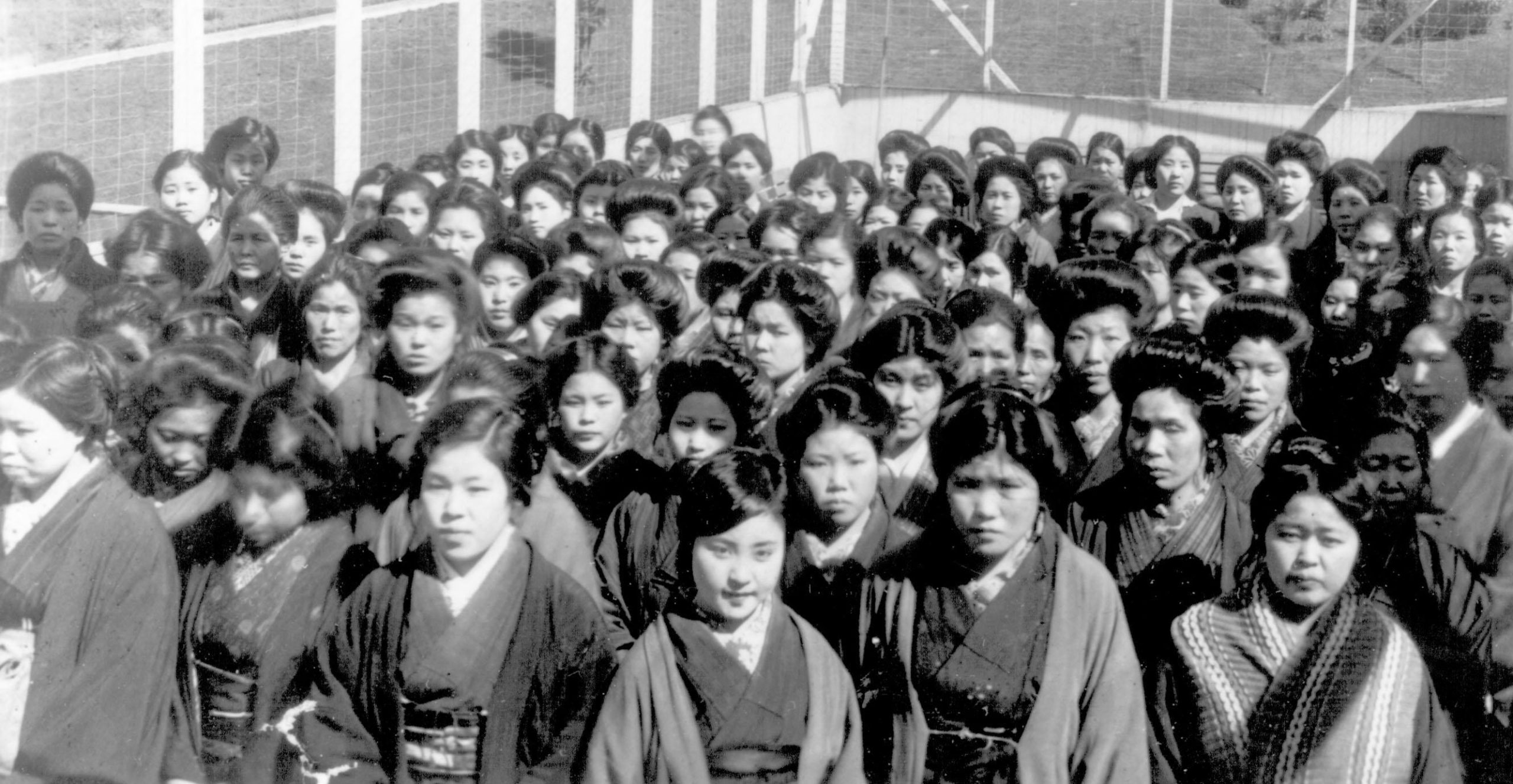

In Picture Bride, Uchida turns her spotlight onto the group of immigrant women known as the picture brides. The term “picture bride” (shashin hanayome) denotes that first generation of early twentieth-century Japanese women who came to the United States in waves between 1908 and 1920 when the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907 placed severe restrictions on Japanese immigration. One strategy for working around such restrictions for Japanese men in America looking for a wife in Japan was to get married by proxy. Facilitated through matchmakers and the circulation of exchange photographs between prospective brides and grooms, Japanese men and women were legally wed when the latter’s name was entered in the family registry (koseki tōhon) in Japan. Thus, men and women became legally wed no matter where they physically resided.

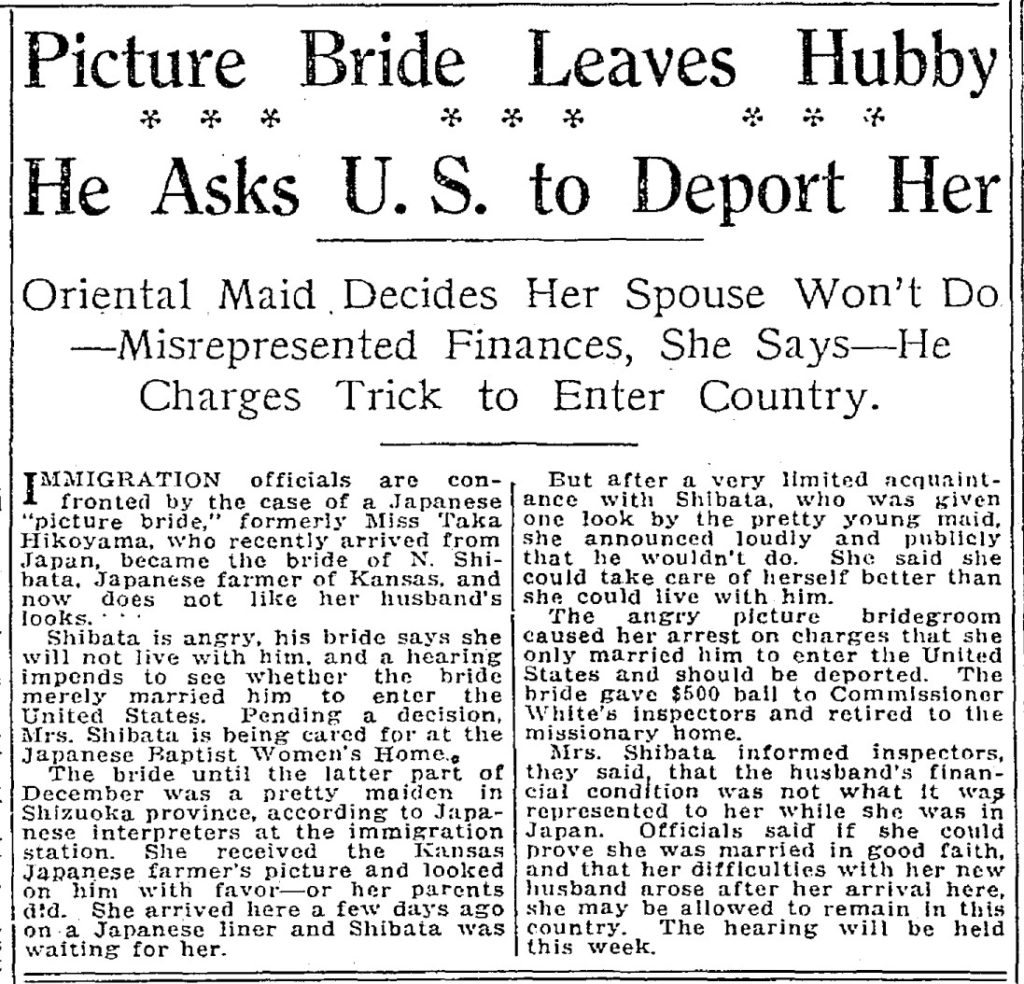

The representation of picture brides became fodder for early twentieth-century US newspaper coverage during a period of growing anti-Japanese agitation particularly on the West Coast. Indeed, sensationalized stories of Japanese brides arriving on American shores “to love, honor, and obey a photograph” not only inflamed the press but resulted in waves of dramatic headlines crafted to entertain a white American readership for well over a decade. Such headlines emphasized stories of mutual disappointment, abandoned brides, failed marriages, and even rebellious women who sought to escape their dire domestic situations by running away from husbands (sometimes leaving behind their small children).

The vast majority of Japanese picture brides and grooms met each other for the first time upon the women’s arrival in ports of entry in Honolulu, San Francisco, the Pacific Northwest, and even Canada. As a historical group, one could say that picture brides took a leap of faith by marrying a photograph before bravely crossing the Pacific into the unknown. Japanese picture bride Asano Terao vividly recalled the experiences of arriving women waiting to meet their husband—many for the first time:

“[They] took out the pictures from their sleeves, and they looked at them really hard to compare the faces. There were many people who said, ‘That person, his face looks very alike, but he is a lot older.’ They sent the pictures from their youth . . . [Some] lied about their age, those who lived here told lies . . . Even though they were in their fifties, they still told them that they were in their thirties or twenties because it was the picture marriage, right?”

According to the terms of the Gentlemen’s Agreement, Japanese women were allowed to enter the US to join their husbands provided they could prove that they would not seek work or become a public charge. Brides were pressured to identify themselves strictly as wives and not laborers when undergoing mandatory screening interviews upon their arrival by a Board of Special Inquiry. When asked when and why she came to America, picture bride Akiko Suda replied, “I came in February 1916 as my husband’s yobiyose wife, as a himin and not as an imin . . . Imin were people who came as laborers. I came as a housewife. There was a difference in our passports. I had a pink permit as a yobiyose and did not need a photograph, while the laborers had green ones.”

While marriage by proxy in Japan formed a legal union, the backlash in the US against the perceived “immorality” of arranged marriages necessitated that some couples marry again once on American soil. Picture bride Harumi Hoshiko recalled that when she arrived in 1915, “We were all married in San Francisco. There was a priest there, and all the picture brides that arrived were married together there. There were many there, and we all lined up to get married.”

The growing political criticism surrounding proxy marriages and the incoming waves of Japanese women—dubbed the “Oriental Menace” by the press—resulted in Japan’s capitulation to US pressure to cease the practice. As of February 25, 1920, the Japanese government announced that the practice of picture marriages would end. The arrival of this historical group of Japanese women onto US shores occurred during a particularly virulent anti-Japanese political moment in US history that reached its crescendo with the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924—which would effectively stop all Asian immigration to the US.

Given the highly visible backdrop of social, cultural, and political anti-Japanese drama that frames the history of this generation of Japanese immigrants in the US, it is hardly surprising that Uchida creatively makes these women the heroic subject of her novel. They are, after all, inspired by the collective stories of her mother’s generation.

Picture Bride follows the story of twenty-one-year-old Hana Omiya who travels by steamship from Oka Village in Japan to San Francisco in 1918 to join Taro Takeda, who is ten years her senior. Hana is fortunate that Taro is a kind man who is intent on being a good husband. Hana and Taro are swept away by a tsunami of historical events that include the outbreak of the 1918 Spanish flu, the rising backlash against the Japanese community in California, and the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor that will catapult the US headlong into World War II, resulting in the subsequent removal and relocation under Executive Order 9066 of all persons of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast.

This narrative arc, mirroring much of Uchida’s own family history—right down to the same family number (13453) assigned to them in camp—devastates the lives of the novel’s Japanese characters and makes for compelling storytelling.

Not long after Hana arrives on American shores, she is warned by Kiku Toda, the boarding house proprietor and fellow picture bride who will become her best friend, “Don’t forget, we are aliens here. We don’t really belong.” This struggle over national belonging has long been part of an American immigrant story. Uchida dares to explore the emotional dimensions of the “forever foreign syndrome” by giving us a window into Hana’s interior life: “She could never be completely herself. It was as though she were going through life pressed down, apologetic, making herself small and inconspicuous, never able to reach out or to feel completely fulfilled. What kind of woman would she have been in her native land, she wondered. Would she have been different? More the self she really was?”

Later, while trying to comprehend the sheer “vastness of the United States,” Hana cannot understand the “hatred and fear of such a giant land” toward the Japanese. “Peril?” she asks incredulously. “We Japanese are a peril to this enormous country? It was beyond belief.”

Picture Bride humanizes the first generation of Japanese immigrant men and women with its intimate look at their dreams, desires, and disappointments over the course of three decades. Uchida’s fictional world is woman-centered with its lens centrally focused on the private and public lives of the Issei women who must deal with the loneliness of Japanese men, juggle the demands of home and work, and raise the next generation of American-born children who will smash the racist myth of the unassimilable Asian.

Hana’s American-born daughter, Mary (born in the same year as Uchida herself in 1921), is a literal study in second generation Japanese self-erasure. Mary is raised by her parents to be “good, obedient and docile,” to study hard and “become a law-abiding citizen, who would one day be accepted and integrated into the fabric of white American society.” Mary fulfills her parents’ immigrant dreams of success, but the cost of her Americanization is steep: She submerges her sense of Japaneseness, elopes with the son of Italian immigrants, and moves so far away from the Japanese American community that she literally watches the drama of incarceration unfold as a kind of “dazed” and detached outsider reduced to observing her family’s ordeal from an emotional and physical distance.

In the world of Asian American arts and letters, Japanese picture brides have received scant attention as worthy subjects of representation. Yoshiko Uchida makes it very clear that stories chronicling the dreams and struggles of the “brave women from Japan who travelled far, who endured, and who prevailed” belong to American literature. The women in Picture Bride never once waver as they hold down the center of the narrative. Confined as prisoners in wartime concentration camps, Hana and Kiku walk arm in arm as they face down another incoming dust storm that threatens to envelop “all of Topaz in its white fury.” “They each crossed an ocean alone to come to this country, and they’re going to survive the future with the same strength and spirit.” Uchida’s picture brides not only bear the unbearable but they stand firm and unafraid.

—

Elena Tajima Creef is professor of women’s and gender studies at Wellesley College and author of Shadow Traces: Seeing Japanese/American and Ainu Women in Photographic Archives.

This is an excerpt of Creef’s foreword to the 2022 re-release of Picture Bride from the University of Washington Press.

[Header: Picture brides arriving at Angel Island, California, c. 1910. Courtesy of California State Parks, Number 090-706.]