March 11, 2019

Yeiko Mizobe So was born in Fukuoka on December 4, 1867 to samurai Nobuhara Mizobe and his wife Ino. She and her three siblings grew up in a fairly privileged household and received private tutoring in the Japanese language and cultural arts. She was married to Isojiro So in March 1888, but became a widow just six months later when her husband died of a brief illness. Despite her rather prim and proper origins, she’d spend the rest of her life upending traditional gender norms and fighting for the independence and empowerment of women.

Following Isojiro’s death, So met American missionaries Orramel and Anna Gulick, and made a decision to convert to Christianity. She sold her belongings and enrolled in Kobe Women’s Seminary in March 1891—joining other Meiji-era daughters and wives sent to Christian seminary schools in order to learn Western habits and culture. Ironically, although these women were often sent to seminary at the behest of their husbands and fathers, the education and increased independence they experienced in the all-women environment turned them into more vocal and active members of Japanese society. In the words of scholar Noriko Kawamura Ishii, they were “no longer innocently passive to male decision-making in both the home and in the public sphere.” [1]

So graduated as a qualified evangelist in April 1893 and worked as a missionary in the Kobe area until she was invited by the Hawaiian Board of Missions, at the Gulicks’ request, to assist with the “acculturation” of Japanese immigrants in the then-territory of Hawai`i. A 27-year-old So arrived on Ō`ahu on May 20, 1895 and, after a tour of the islands, immediately recognized the need for a shelter that would provide housing and protection to Japanese immigrant women, primarily picture brides, experiencing abuse.

Yeiko Mizobe So, seated center, with some of the women and girls she worked with in the shelter for abused picture brides that she started and ran from 1895 to 1905, and the Home for Neglected Children, which opened in 1905.

Courtesy Hawai`i Council for the Humanities.

Picture brides were especially vulnerable to domestic violence and sexual abuse. Most spoke little or no English, were reliant on their husbands financially, had no family members in their new community, and lived on isolated sugar plantations far from legal or social services. The limited network of social service agencies that did exist was dominated by white missionary women who, however well-intentioned they might have been, lacked the nuanced cultural and linguistic knowledge to offer these women meaningful assistance.

So, on the other hand, was able to both relate to these women’s experience as immigrants far from home and provide culturally relevant services in their native language. In 1895, not long after arriving in Hawai`i, she established the Japanese Women’s Home for Abused Picture Brides on Alapai Street in Honolulu, with financial support from the Japanese Christian Church.

Rather than treat the women who came to her as helpless victims, So encouraged them to take on responsibilities to help run the home—cooking, cleaning, managing the nursery, and helping to put on recreational and cultural activities like plays—in addition to offering educational programs that would help them become self-sufficient. So even organized classes in gynecology and reproductive health to ensure that women had the knowledge and autonomy to make informed decisions about their own bodies.

So’s efforts were not warmly received within the larger Japanese immigrant community. Angry husbands would show up outside the home to demand their wives come back to them, often threatening So and her staff when they intervened. Male community members—already upset over the (somewhat) more independent status Issei women were achieving as wage earners outside the home, as well as rising rates of divorce—decried So and the Japanese Women’s Home as yet another example of Issei women usurping patriarchal authority. But in spite of consistent threats and scorn from abusers and those who enabled them, So persevered.

Over the next ten years, from 1895 to 1905, So provided shelter, safety, and education to more than 700 women. In addition to her work at the Japanese Women’s Home, she also supervised the reception of picture brides at the Hawai`i Territorial Immigration Center, providing much-needed oversight to ensure that the women were treated fairly and humanely by immigration officials. Eventually, the immigration center took over the care of picture brides in need of assistance, and in 1905 So founded the Home for Neglected Children. Under her leadership, the home took in 421 children over the years, from both rural plantations and urban areas like Honolulu.

Photograph courtesy of Nu’uanu Congregational Church archives.

So retired in 1931, after nearly forty years of active social work in the Hawai`i Japanese community. She died at Queen’s Hospital the following year, and was survived by her daughter Esther, whom she’d adopted from the children’s home and raised as a single parent. The legacy she left behind is a powerful antidote to the common depiction of Issei women as silent, passive background players—and a reminder that our history is full of brave, resourceful, visionary women, if we take the time to look for them.

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Communications Coordinator

[1] For a more extensive picture of So’s life, read Kelli Yoshie Nakamura’s illuminating essay, “Yeiko Mizobe So and the Japanese Women’s Home for Abused Picture Brides (1895-1905),” in Amerasia Journal 36:1 (January 2010).

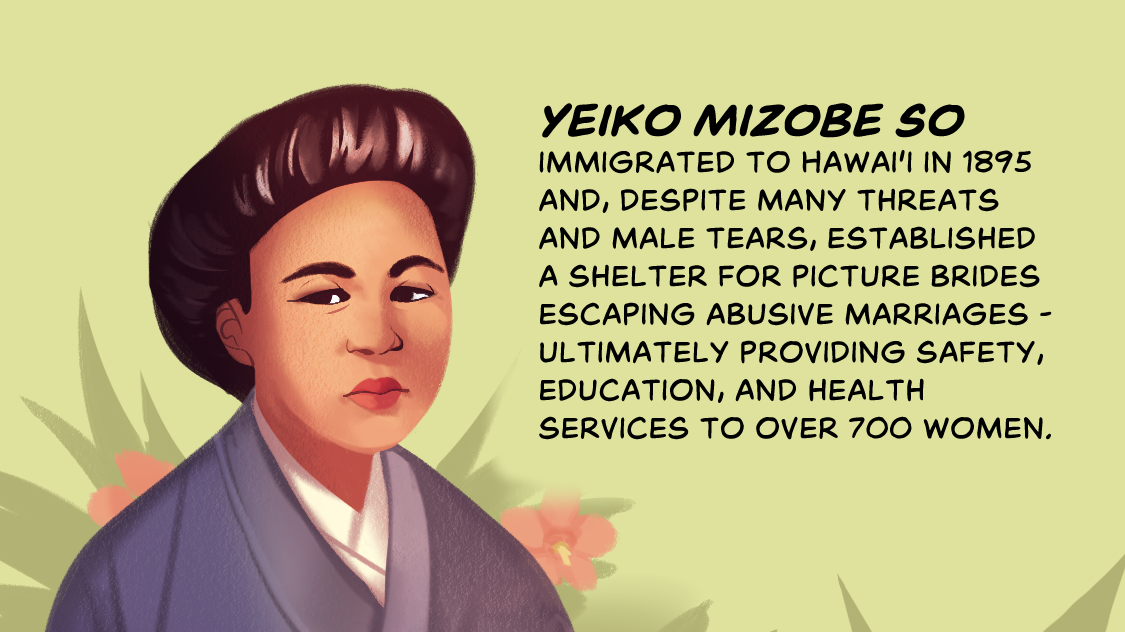

Header image: original artwork by Kiku Hughes. Kiku is a comics artist living and working in the Seattle area. Her work has been featured in “Beyond: A Queer Sci-Fi and Fantasy Comic Anthology”, “Elements: Comic Anthology by Creators of Color” and Short Box Comics Collection. She is currently working with First Second Books to publish her first graphic novel, about Japanese American incarceration. Funding for Kiku’s work was generously provided by a grant from the Seattle Office of Arts & Culture.