October 28, 2015

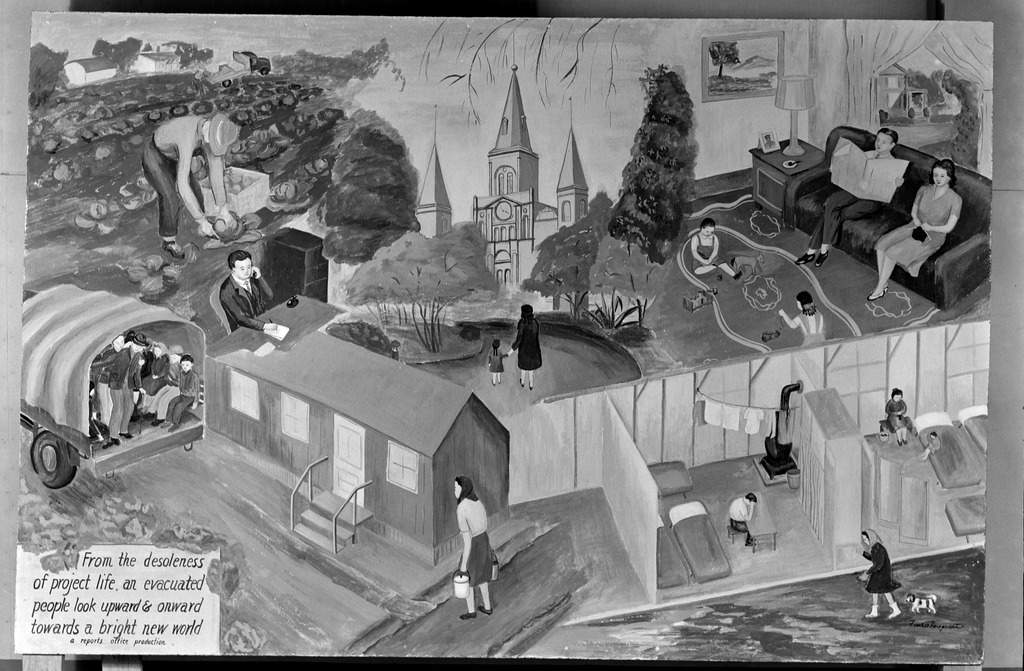

“The stage on which the Irrigator introduces itself is 68,000 acres of untamed desert. Minidoka, as we know it now, is a vast stretch of sagebrush stubble and shifting, swirling sand–a dreary, flat expanse of arid wilderness. Minidoka, in September of 1942, is the sort of place people would normally traverse only to get through to another destination. But we, ten thousand, from the climatically temperate cities and the lush, verdant valleys of coastal Washington and Oregon, are not passing through to a ready-made civilization.”

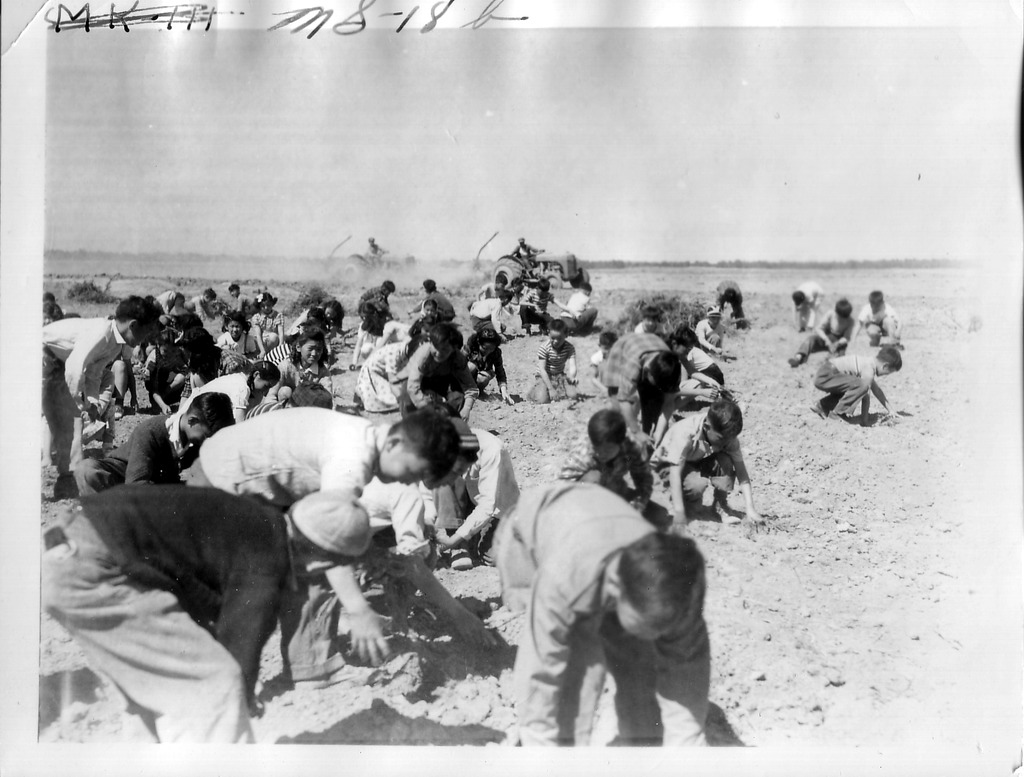

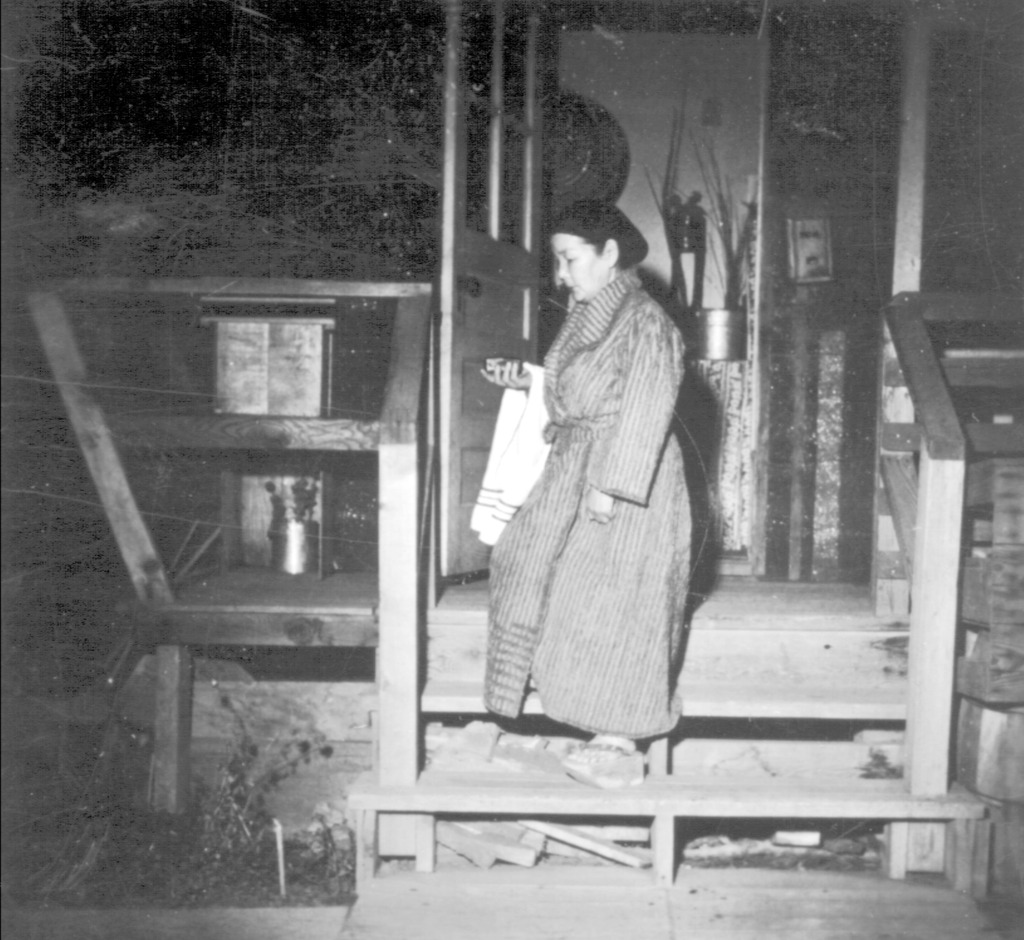

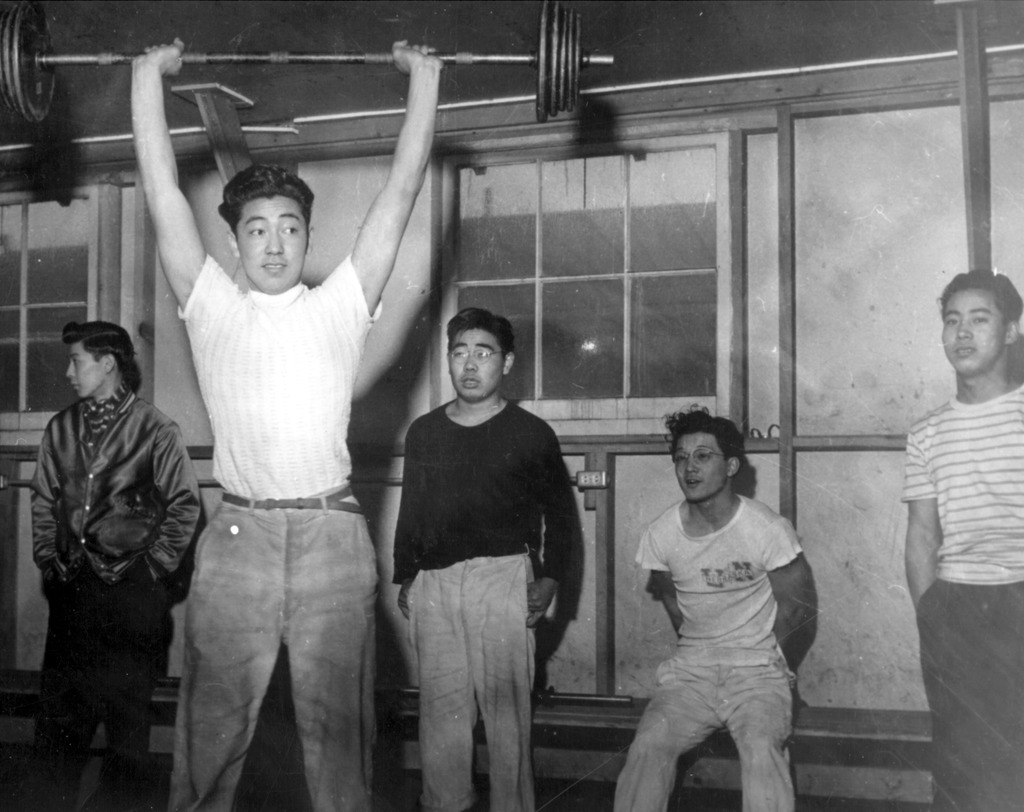

Despite the oppressive summertime heat and dust storms, coupled with freezing cold, flooding, and snow in the winter, residents worked hard to carve out a life for themselves at Minidoka. On top of the degradation of being classed as enemy aliens and having to give up their homes and lives, the prisoners maintained peaceful relations with camp administrators at first. However, a more turbulent relationship developed after the barbed wire fence surrounding the camp was completed. When the first incarcerees arrived, the barbed wire fence was unfinished, which allowed them to venture out into the nearby sagebrush plains to find much-needed fuel to burn. The completion of the fence prevented this and, to many, came to stand for yet another intolerable and humiliating symbol of their oppression. Some rebelled and tried to dismantle the fence, but the contractor electrified it without the knowledge of the administration, causing further tension.

In 1943, the loyalty questionnaire issued by federal officials exacerbated tensions.[19] While twenty-five percent of those Nisei who volunteered for the Army came from Minidoka,[21] others resisted the military draft making a statement by defying it. In 1944, thirty-eight men were apprehended for draft evasion.

Finally, in December 1944, the War Relocation Authority announced the closures of all camps. At that time, seventy-three percent of those removed from the West Coast were still at the ten WRA centers across the United States.[23] By September 1, 1945, W.E. Rawlings became the project director, and he stated in his Project Director’s Narrative that there were still 3,000 Nikkei at Minidoka. Rawlings said those who were left were old, sick, or incompetent. Many were given a three-day notice to vacate the premises, so the site could be closed on time. Only one person was evicted due to refusing to move. Rawlings mentioned that it only took one eviction to cut this behavior.[24]

On January 17, 2001, the Minidoka National Historic Site was designated as the 385th unit of the National Park System by President Bill Clinton as the Minidoka National Historic Monument, including 73 acres along the North Side Canal. In 2008, the site was designated as a National Historic Site by President Bush. Now, former incarcerees and their families return to the Monument annually as part of a four-day pilgrimage and Civil Liberties Symposium.

Scroll through the photos below for a glimpse into life at Minidoka. Visit this HistoryPin collection for additional photos and oral histories; visit the Densho Encyclopedia for footnote source material, as well as additional information and resources.

View oral history interviews and more photos from Minidoka in this HistoryPin Collection:

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications Manager

Portions of the introduction were excerpted from the Densho Encyclopedia article by Hanako Wakatsuki.