November 23, 2021

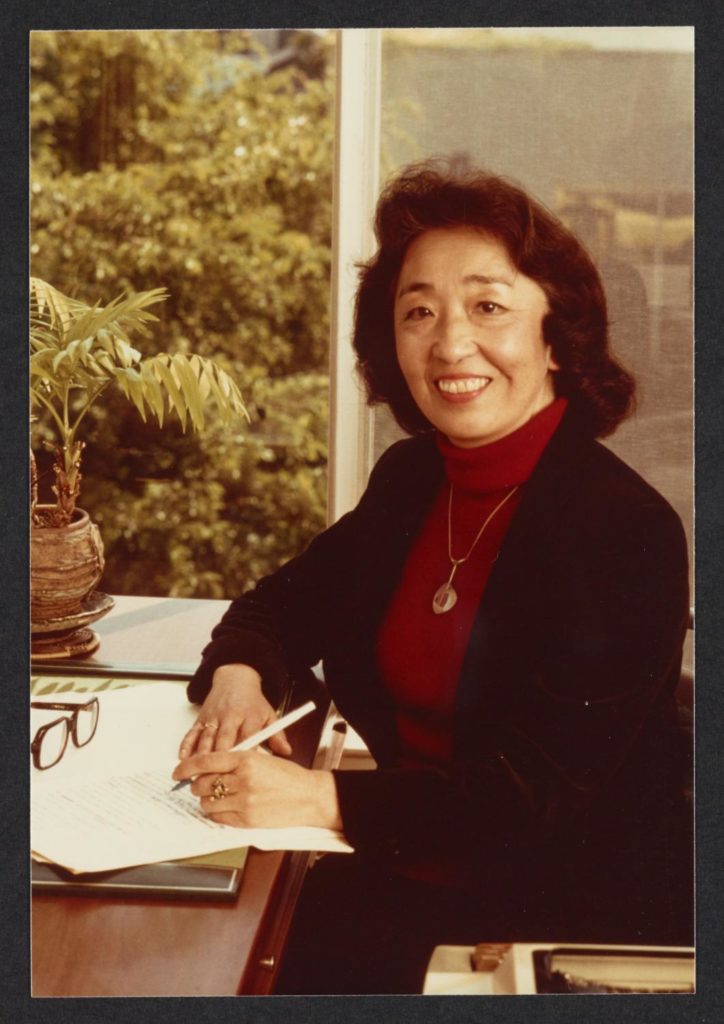

I have long been a fan of Yoshiko Uchida, a Berkeley-based writer best known for her children’s and young adult books about the World War II forced removal and incarceration. But her long writing career included much more: pioneering children’s books set in Japan or in Japanese American communities published just a few years after the end of the war, a widely-cited memoir and adult novel, and many more articles and short stories. What would have been Uchida’s 100th birthday is this week, which provides an opportunity to revisit her life and career.

Yoshiko Uchida was born on November 24, 1921, to Issei parents Dwight Takashi Uchida (1884–1971) and Iku Umegaki Uchida (1893–1966). Both were Christian and graduates of Doshisha University. By the time Yoshiko and her older sister Keiko (1918–2008) were born, her parents were well established, with Dwight working for the San Francisco branch of Mitsui and Company, and the girls enjoyed a relatively privileged upbringing. The family lived in a rented home in an area of Berkeley that had been previously restricted to whites. The girls took piano lessons and the family went to concerts and museums, while also taking memorable vacations to the East Coast and to Japan.

Though sickly as a child, Yoshiko graduated from high school in two and a half years and enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, at age 16. She majored in English, history, and philosophy. Excluded from many university institutions on account of her race, her friends and dates were almost exclusively other Nisei students there. Meanwhile, Keiko went to Mills College, graduating in 1940 with a degree in child development. But like many other accomplished Nisei, she was not able to find a commensurate job until years later.

As with other Nikkei families, the outbreak of World War II brought dramatic changes. As a community leader with ties to Japan, Dwight was arrested on December 7, held first at the Immigration Detention Station in San Francisco, then sent to the Missoula, Montana internment camp. As with the rest of the Bay Area Nikkei, the Uchidas were sent to Tanforan, where they were among the unlucky ones to be held in a converted horse stall. After a few months, Dwight was “paroled,” which allowed him to rejoin the family when at Tanforan before they were sent to the Topaz, Utah, concentration camp.

The Uchidas did what they could to contribute their talents and educational backgrounds to camp life. At Tanforan, the sisters started a nursery school, and Yoshiko later became a second-grade teacher, while also attending adult classes in art and first aid. Seeming to recognize the historic nature of her confinement, Yoshiko also documented her experience through drawings and paintings, and through a journal and letters.

At the same time, the difficult living conditions and accumulated indignities began to pile up: a beloved dog left behind in the care of a stranger that died soon after; getting a prized diploma from the University of California in the mail at a concentration camp; the miserable facilities of the camp schools she taught at.

As she wrote in Desert Exile, her first camp memoir:

“I worked hard to be a good teacher; I went to meetings, wrote long letters to my friends, knitted sweaters and socks, devoured any books I could find, listened to the radio, went to art school and to church and to lectures by outside visitors. I spent time socializing with friends and I saw an occasional movie at the Coop. I also had a wisdom tooth removed at the hospital and suffered a swollen face for three days. I caught one cold after another; I fell on the unpaved roads; I lost my voice from the dust; I got homesick and angry and despondent. And sometimes I cried.”

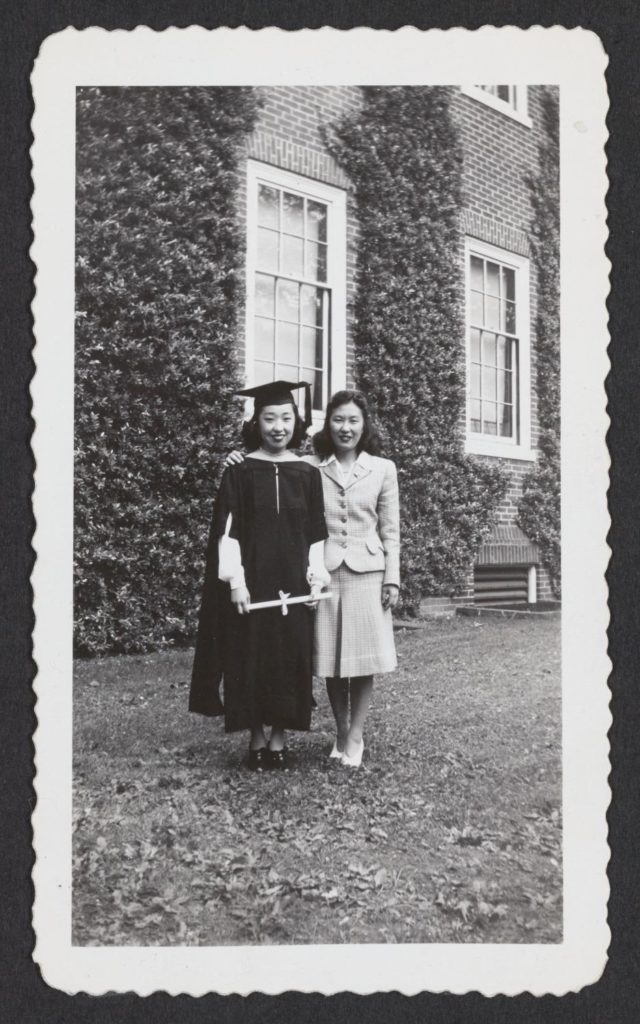

Yoshiko was able to leave Topaz in May 1943, having received a full scholarship to pursue a master’s degree at Smith College. Since Keiko had received a job offer at nearly Mt. Holyoke College, the sisters left Topaz together in June. After finishing her M.Ed at Smith, Yoshiko took a teaching job in Philadelphia, while also pursuing an interest in writing. She later moved to New York and worked as a secretary, which gave her more time to write. She submitted short stories to mainstream magazines and journals, resulting in a pile of rejection slips. Her breakthrough came with the 1949 publication of The Dancing Kettle and Other Japanese Folk Tales, which was met with great acclaim.

Many other successful children’s books followed, a mixture of stories set in Japan, stories set in the U.S. featuring Japanese American and Japanese characters, and another book of folk tales. These were notable works for their time, when portrayals of non-white characters in children’s books were rare, and when most of those writing about non-white communities were themselves white. Uchida told a later interviewer, “I wanted to write stories about human beings, not the stereotypic Asian. There weren’t any books like that in the early ’50s when I started writing for children.”

Read today, these early books come off as enjoyable but a bit naïve, especially given her own life experiences. New Friends for Susan (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1951), for instance, is set in prewar Berkeley and features a presumably Sansei protagonist enjoying a completely idyllic childhood, where there is no conflict and no racial discrimination and where mothers all seem to be of the stay-at-home variety with the time and means to aid their daughters with whatever they need. Mik and the Prowler (1960) is more complex, but even here, everyone—even the villains—turn out to have good hearts, and racism is again non-existent.

The Japanese American books present the Nikkei families as nearly indistinguishable from any other suburban American family save for some elements of Japanese culture in the home. Even the ones set after the war notably avoid any mention of the incarceration. But in noting these elements of her early work, we should not overlook the fact that Uchida was putting a human face on Japanese and Japanese American characters just a few years after the mass incarceration. As with the contemporaneous work of Taro Yashima and Gyo Fujikawa, this was no small thing at that time.

In his recent book From Confinement to Containment: Japanese/American Arts during the Early Cold War (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2019), Edward Tang sheds new light on her 50s and early 60s work. He makes the case that Uchida was in fact writing and talking about her incarceration experience in this time period—and trying unsuccessfully to publish such accounts—despite the absence in her books. Tang notes a ten-page camp memoir that she wrote in 1952, as well as a contemporaneous short story based on the notorious shooting of an Issei inmate at Topaz, both of which were repeatedly rejected by magazines. Core elements of both of these pieces found their way into her later works. He also notes that she used the platform that the children’s books gave her to talk openly about her incarceration and about racism in interviews and other publicity for the early books. He calls these early stories and words—along with The Full Circle, a 1957 book set in Japan about the toll of the war on a liberal Japanese family—”literary experiments” that led to her later camp-centered work.

Citing rising consciousness bv Sansei about their family’s incarceration experience and a gradual change in mainstream attitudes, Uchida eventually turned to these stories in her books. I’ve written a fair amount about those post-1970 camp centered books—the young adult novels Journey to Topaz (1971) and Journey Home (1978); the children’s picture book, The Bracelet (1976); her novel, Picture Bride (1987); and her two memoirs, Desert Exile (1982) and The Invisible Thread (1991)—so I won’t add too much here. All are important works that still hold up today. I do have a particular affection for the last, her “young adult” memoir that I prefer to her earlier “adult” one. Lyrical, evocative, and moving, it is both deeply personal and universal. If I had to choose one book about camp to give to a child of appropriate age, I would choose this one.

I’ve long felt that Uchida has been underappreciated. Part of that has to do with the general treatment of literature for children as being less important than literature for adults, despite the often larger audience books like Uchida’s reach and the more impressionable nature of that audience. I think part of it has to do with Uchida’s relatively early passing—in 1992 at age seventy—and that she never married and didn’t have children to carry on her legacy. She also died before Densho could interview her, before she could be featured in the many films and videos that have come in the era of state and federal funding of incarceration related projects, and before she could be honored by one of the many organizations devoted to Japanese American history that were just getting started at that time.

As it turns out, Heyday Books is publishing a 50th anniversary edition of Journey to Topaz with a new foreword by Traci Chee (whose recent book, We Are Not Free, is sort of a contemporary version of Journey to Topaz) as well as a beautiful new cover art by friend-of-Densho Patricia Wakida. I hope this is a harbinger of things to come.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

For more information, see the Densho Encyclopedia article on Uchida (which this piece draws from) and her papers and photo collection at UC Berkeley.

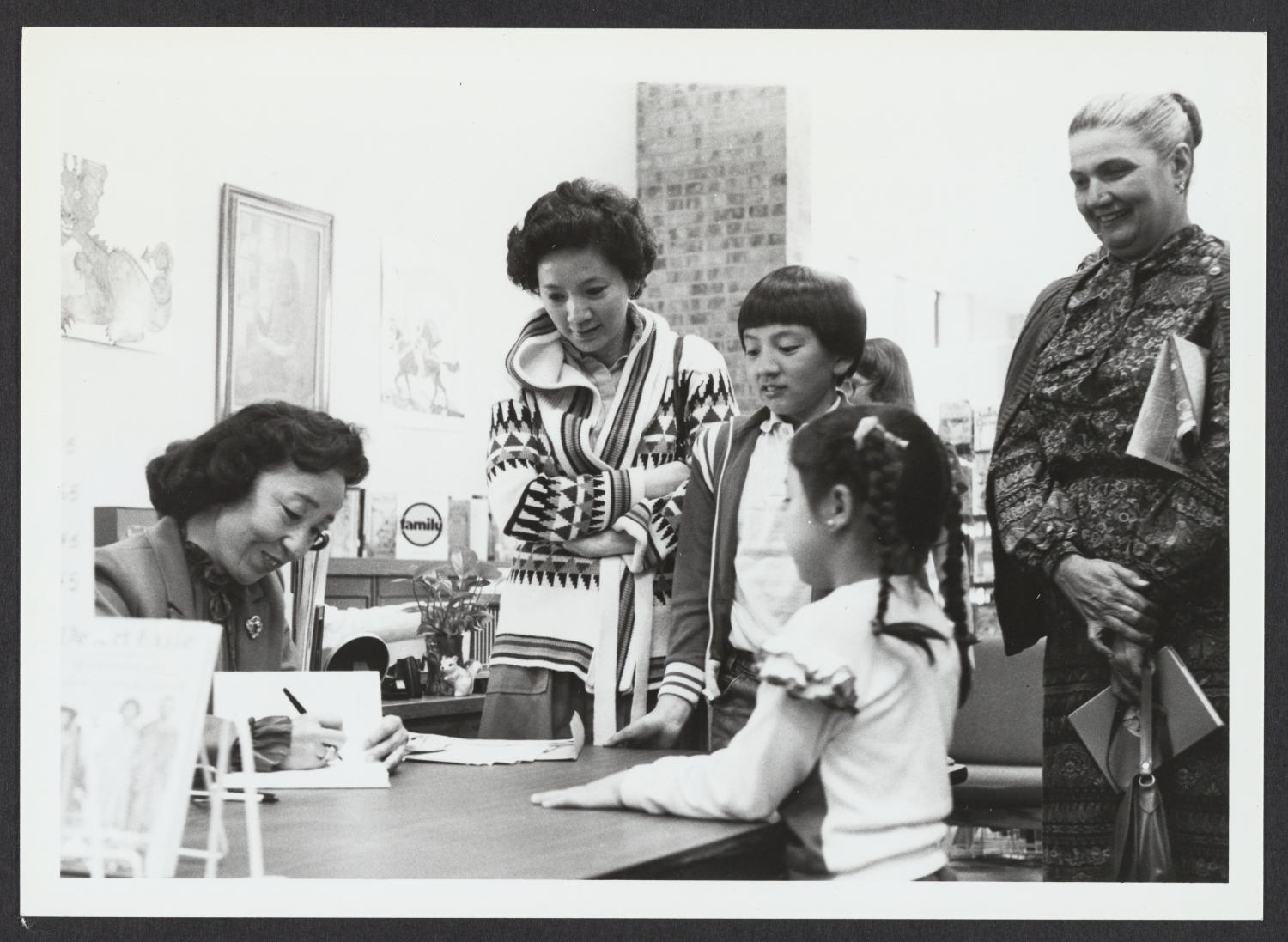

[Header: Uchida signing a book for a young reader in Sherman, Texas. March 29, 1984. Courtesy of the Yoshiko Uchida photograph collection, UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library.]