December 16, 2021

In this latest edition of “Ask a Historian,” Densho Content Director Brian Niiya digs into the history behind a photo taken in a mess hall at Topaz concentration camp —and what it tells us about the incarcerees who worked there.

Photographer Brad Shirakawa is part of a group working to document the history of Japanese Americans in Alameda, California in partnership with Densho. He writes:

I have a question about a photo of waitresses from Mess Hall 23 in Topaz. I found items at Densho about them, but not much of a description of what they did for their job. It seemed odd to me — why would you need waitresses in the mess hall? There were no ‘orders’ to take, so maybe they cleaned up?

In both the so-called “assembly centers” and War Relocation Authority (WRA) concentration camps, the communal mess halls were a central part of inmate life and the largest employer of inmate workers. Though there were white stewards who controlled the food supply and ostensibly managed the workforce, inmate workers had a fair amount of autonomy at the individual block mess hall level. At a typical WRA block mess hall—there was generally one per block, with each block having a population of around 250 people—a chief cook was in charge and oversaw the hiring of 32 to 36 staff members, around 10 of whom were waiters or waitresses. Most of the cooks were Issei, while most of the servers and dishwashers were Nisei, with the former being mostly female and the latter mostly male.

Camp mess halls employed two distinct systems in serving the inmates, varying by camp, time, and even from block to block. In the cafeteria style, inmates would line up and be served their food by mess hall workers, after which they would seat themselves. “You got one plate with everything on it—meat, vegetables, everything,” recalled Nellie Mae Nakamura, a former waitress at Heart Mountain. In a mess hall serving family style, food would be placed on the tables in large platters before the inmates were allowed in.

According to Frank Muramatsu, who was a busboy at the Portland Assembly Center, “we would bring… the dishes out from the kitchen, and they [the waitresses] would set it up, and then we would bring the food out. And the food was placed on the plates before a bugle was blown to call the people in to eat.” The inmates would then sit at the tables and serve themselves from the communal platters.

There were pros and cons to each system from both the inmate and administration perspectives. The family style system required more food but was more conducive to having multiple shifts in cases where the block population was larger than the seating capacity of the mess hall, which mostly took place in the assembly centers and the early weeks of the WRA camps. But while cafeteria style systems seemed to allow for greater portion control, there were sometimes problems in the serving of small children as well as longer lines and resulting line cutting issues.

It’s not clear which systems most inmates preferred, though a report from Jerome indicates that inmates disliked the family style system due to the “delay in getting dishes washed,” presumably because all of the inmates ate—and finished eating—at the same time.

The duties of the waitresses varied depending on the system. In a family style system, they played a more traditional role, bringing out the food and setting the tables before the inmates were allowed in. They then served drinks and replenished the food supply as necessary. After the inmates had finished eating, the waitresses would bus the tables. They had perhaps less to do in the cafeteria system, since inmates carried their filled plates to the table and also bussed their own dishes afterwards. They did still set the tables beforehand—”I set out pitchers of water and milk, teapots, butter, salt and pepper, and cups,” recalled Nakamura—and refilled drinks subsequently. Afterwards, Mika Hiuga, a waitress at Tule Lake, remembered that “we have to clear the table, mop the floor, sweep the floor.” Sometimes, they would also help the dishwasher dry dishes, and periodically clean windows and other parts of the mess hall.

The ever observant James Sakoda, a Kibei field worker for the University of California’s Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study whom I’ve written about before, noted the pros and cons of being a mess hall server. On the one hand, the hours were fairly short. Though one had to be there for all three meals in most cases, the servers worked only around six hours a day, since they had to be there an hour before and an hour after each meal was served. This left ample time for other pursuits, such as adult education classes or sports. He also noted a kind of camaraderie among the mostly young Nisei workers who would “usually talk a great deal and claim that they have a great deal of fun working in the mess hall.” On the other hand, being a server was seen as an unskilled, relatively low-status job vs. “white collar” office work, and, according to Sakoda, drew “country” people with less work experience. Most servers also received the lowest WRA wage of $12 per month.

Regardless, the servers and other mess hall workers made up a large part of the inmate workforce, and many Nikkei women held such jobs, including Esther Takei Nishio, Yuri Kochiyama, and Hisaye Yamamoto. No doubt drawing on her experiences, Yamamoto makes the narrator of her classic camp-set short story “The Legend of Miss Sasagawara” a waitress. Another writer, Yachiyo Uehara (technically an Issei born in 1916, she came to the U.S. at age eight and so has more in common with older Nisei), sets her short story of friendship and small pleasures in camp, “A Piece of Cake,” among a community of waitresses in a Heart Mountain mess hall, also based on her own stint as a waitress there.

While mess halls appear frequently in both academic or popular literature on the incarceration, the focus has mostly been either on (a) their role in the erosion of Japanese American family life or (b) their roles as sites of resistance or unrest. But the experiences of servers and other inmate staff in camp mess halls is another aspect of camp life that remains largely untold.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

Each month, Brian answers questions from Densho readers about Japanese American WWII incarceration. Catch up with his previous responses to questions about how mothers fed their babies in camp and where to find records on family members interned by the Department of Justice. Have a question of your own? Send it to info@densho.org!

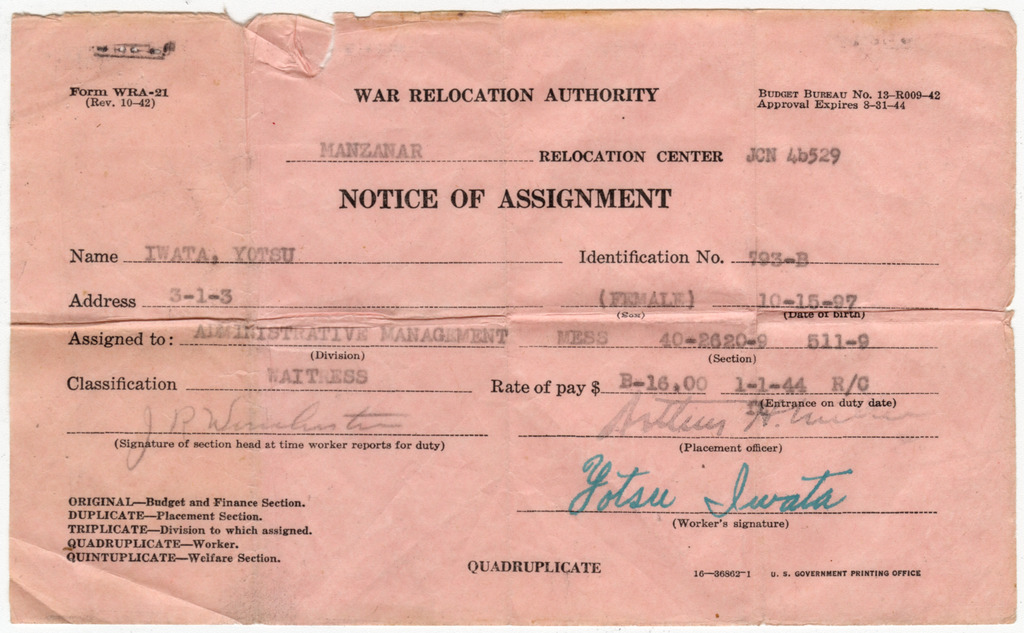

[Header: Servers and other staff at a mess hall in Manzanar. Courtesy of Manzanar National Historic Site and the Shinjo Nagatomi Collection.]