October 4, 2022

In this latest query from Densho Content Director Brian Niiya’s “Ask a Historian” series, Shelley Lekven asks what funerals looked like for Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II:

Do you have any information about how funerals were handled in the assembly centers? Were inmates barred from attending burials of loved ones and only allowed to have a memorial or funeral in camp?

There could be a lengthy article written on funerals in the various incarceration sites that held Japanese Americans during World War II. But I’ll try to cover the highlights briefly.

Though the questioner asks about the “assembly centers,” I’m going to take a broader view of the question. According to official records, 128 people died in the WCCA “assembly centers” and another 1,862 in the War Relocation Authority (WRA) concentration camps. There were undoubtedly hundreds of others who died in the internment camps run by the army or Justice Department.1

From the administration perspective, funerals were in some ways a microcosm of other aspects of camp life in that there was initial uncertainty and a sense that policy was being made up on the fly before evolving into a policy that tried to balance practicality, compassion, and expense in a matter that satisfied no one. From the inmate perspective, funerals were yet another reminder of the travails of incarceration and a locus for unrest in some cases. But they also evolved in ways that couldn’t have happened on the outside and became symbols of status in barbed wire communities in which the normal markers of status had been stripped away.

Whether in short-term detention sites run by the army/Justice Department or WCCA, initial policies were uncertain. When Hisahiko Kokubo died at Sand Island in March of 1942, administrators initially denied permission for a funeral before allowing a memorial service on site and later allowing Kokubo’s remains to be sent back home to Kauai, where a funeral was held. A Buddhist priest interned at Kalaheo Stockade was given special permission to leave so as to officiate the funeral.2

In assembly centers—which were also typically close to the places where their inmates had lived prior to the war—permission was also sometimes granted for cremations and funerals to be held back home. Natsuye Furusho, who died soon after giving birth at Tanforan, was buried in Centerville, where she had lived before the war, and the family was able to get a permit to go there for services. Inmates were also sometimes allowed to leave to attend funerals of relatives who had died in institutions such as hospitals or sanitariums. But as Doris Hayashi noted in her diary from Tanforan, this process involved “a lot of red tape” that resulted in delays in leaving the camp, something that “was really terrible considering it was a funeral.” And the numbers allowed to leave were limited: just five people in the case Hayashi described. There were also substantial costs involved, as inmates had to not only pay for their own transportation, but that of white escorts who had to accompany them.3

According to Tamie Tsuchiyama, in her report from Santa Anita, memorial services in the assembly centers were not allowed initially “for fear of lowering the morale of the population,” but later were allowed. Eventually, a system for funerals evolved that saw the WCCA agree to pay for inmate funerals with certain limitations. According to a June 10, 1942 memo from R. L. Nicholson in the WCCA main office to individual camp managers, The WCCA would pay costs for a hearse, minister, grave site and grave service up to $50, with total burial expenses limited to $85. A local undertaker was contracted by each assembly center manager, and cremations were done by local crematoria. Given the proximity to home, remains were often buried in local cemeteries.4

This basic structure continued in the WRA camps, as the WRA paid for funerals up to a limit, with a local undertaker and crematorium contracted by each camp to handle all deaths. Perhaps because of its size, Poston actually had its own crematorium on site, and the contract mortician lived in the camp. In other camps, the remains had to be taken out of the camp to one of the local towns for cremation.

Since the camps were considered temporary, there were initially no burial grounds. While some well-heeled inmates were able to pay for remains to be buried in cemeteries near their prewar homes, most kept the ashes of loved ones in urns for future interment. Eventually, most camps did have cemeteries, though relatively few were buried in them, given the uncertainty of who would care for the grave sites after the camp closed.5

Writing about funeral practices in Gila River, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) fieldworker Robert Spencer noted that funerals became relatively elaborate compared to the prewar period, especially among rural populations that predominated at that camp and among Issei. While the WRA’s willingness to pay for funerals up to an $87 limit allowed some poorer inmates to have “a somewhat more elaborate funeral display” then they might otherwise have been able to afford, it covered only a fraction of the cost for most services and Spencer writes that many families “went heavily into debt” to pay for more elaborate funerals. Adding to the expense was the fact that koden (monetary gifts to help defray funeral costs) was discouraged by both inmate leaders and the administration, given the paltry wages the inmates received. But in some cases, funeral practices might have been simpler as well. In a 1945 Community Analysis Section report from Poston, Paul Higashi noted “a lesser degree of elaborateness” in funerals there, especially in the early months, and the more casual dress and less elaborate decorations leading to a more casual atmosphere relative to prewar times.6

Other adaptations to funeral customs stemmed from the shortages brought about by the concentration camp environment. With fresh flowers in short supply, most flowers were paper fabrications. Church groups as well as craft classes and women’s clubs made flowers out of crepe paper to supply the steady stream of funerals. The Reports Office was charged with taking funeral pictures until inmate-run photo studios were started by the co-ops in some camps. Particularly in the early months of the WRA camps, the lack of Buddhist priests also created a problem, and in some cases, funerals were performed by trainees or even by Protestant clergymen, as in the case of Reverend Daisuke Kitagawa, who once conducted a funeral for a Buddhist girl in camp. This issue presumably subsided as more Buddhist priests were paroled from Justice Department camps to WRA camps.7

The opposite situation—a surfeit of Buddhist priests—led to unusual funerals in the army/DOJ internment camps. In his internment memoir, Kumaji Furuya cited the splendor of the “voices of dozens of Buddhist priests reciting sutras,” creating a situation at Camp Livingston where “none of us in our normal life would have been given a funeral with more than eighty priests and ministers in attendance.” Yasutaro Soga wrote of a grand funeral at Lordsburg that featured dozens of ministers that would never take place in normal life. “Upon seeing this spectacle, someone joked, ‘If you have to die, now is the time,'” wrote Soga. But as Furuya noted, the spectacle of such funerals was also leavened by the fact that there were “no loved ones present at the funeral,” a sad fact of internment in such distant places.8

Finally, funerals sometimes took on great symbolic value, in particular in key episodes of protest and unrest in the concentration camps. After the infamous shooting of James Hatsuaki Wakasa by a guard at Topaz in April 1943, inmate unrest led to work stoppages and culminated in a large funeral held over the objections of the administration. At Tule Lake, a truck accident that injured many farm laborers and killed Tatsuto Kashima led to demands for a public funeral that was also denied. As at Topaz, inmates held a large funeral as a means of protest regardless. Internees at Lordsburg were also refused permission for a funeral for two men shot to death by guards on their way to the camp. In protest, internees refused to assemble the following day as ordered, observing the deaths in private. After lodging a complaint with the Spanish consul, they were allowed a small funeral limited to forty people three weeks later.9

Later in the war, large public memorial services were held in WRA camps for Nisei soldiers from that camp (or whose families were incarcerated at that camp). Some credit these ceremonies for changing views of Nisei military service among the Issei, many of whom had previously disapproved of such service.10

There is much more to be written about funerals in the concentration camps, but it should suffice to say that the various adaptations and purposes they serve have much to tell us about inmate and administration views of the incarceration.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

References

1. John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 375; The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, [1946]), 8.

2. Duncan Ryuken Williams, American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2019), 51.

3. gayle k. yamada and Diane Fukami, Building a Community: The Story of Japanese Americans in San Mateo County, edited by Diane Yen-Mei Wong (San Mateo, Calif.: AACP, Inc., 2003), 88; Doris Hayashi diary, May 16, 1942, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records (JAERR), Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B12.00 (1/5); Charles Kikuchi Diary, June 27, 1942, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder W 1.80:02**; Robert F. Spencer, Case History I (Harry Osaka), BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder T1.9939. Spencer, a Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) fieldworker at Gila River, was assigned by WRA administrators to accompany Osaka, an inmate from Fresno, to attend his mother’s funeral; stricken with cancer, she had remained behind at the Fresno County Hospital where she had passed away. Osaka had to pay for both his and Spencer’s expenses. Ever the anthropologist, Spencer used the trip to quiz Osaka on his reactions to the incarceration.

4. Tamie Tsuchiyama, “A Preliminary Report on Japanese Evacuees at Santa Anita Assembly Center” July 31, 1942, p. 37, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B8.05; Memo, R. L. Nicholson to assembly center managers, June 10, 1942, Deaths and Burials—Correspondence, Instructions and Teletypes, Portland Center Manager, Portland Assembly Center General Correspondence File, Reel 239, National Archives, San Bruno branch; E. A. Dunn [FAC assistant manager] to R. L. Nicholson, June 25, 1942, Deaths and Burials, Fresno Center Manager, General Correspondence File, Fresno Assembly Center, Reel 313, National Archives, San Bruno branch; E. R. Gallagher to John J. McGovern, July 10, 1942 , Deaths and Burials, Puyallup Center Manager, General Correspondence File, Fresno Assembly Center, Reel 103, National Archives, San Bruno branch.

5. Robert F. Spencer, “Japanese Buddhism in the United States, 1940-1946: A Study in Acculturation,” pp. 168–71, Ph.D dissertation, July 1946, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder W 1.93; Paul Higashi, “Funerals in Poston,” Poston Community Analysis Section Report No. 79, May 23, 1945, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder J3.21:3; Verlin Y. Yamamoto and Tetsuo Sugiyama, “Report on Poston Hospital,” June 3, 1943, 1–2, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder J2.73.

6. Spencer, “Japanese Buddhism in the United States,” 168–71; Higashi, “Funerals in Poston.”

7. D. A Conlin, Adult Education [Poston] Final Report, pp. 5–6, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder J5.50:28; Constance B. Kimmerling. Report of the Welfare Section, Minidoka Relocation Center, p. 42, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder P6.00:23; Poston Press-Bulletin, Sept. 22, 1942; Charles Kikuchi diary, Oct. 28, 1942, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder W 1.80:07**; Joe McClelland, Final Report, Reports Division, Amache, p. 47, December 14, 1945, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder L7.00:24; Final Report: Reports Division, Rohwer, p. 3, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder N5.00:2; Diary, Mrs. Elmer Shirrell [Eleanor Jones Shirrell], June 6, 1942, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder R 25.10:1**; Williams, American Sutra, 341–42n17.

8. Suikei Furuya, An Internment Odyssey: Haisho Tenten, translated by Tatsumi Hayashi, foreword by Gary Y. Okihiro, introduction by Brian Niiya and Sheila Chun (Honolulu: Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai’i, 2017), 103–04; Yasutaro [Keiho] Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire: The World War II Internment Memoirs of a Hawai’i Issei, translated by Kihei Hirai (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008), 91.

9. Sandra C. Taylor, Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment at Topaz (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 139–42; Brian Masaru Hayashi, Democratizing the Enemy: The Japanese American Internment (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 151–52; Donald E. Collins, Native American Aliens: Disloyalty and the Renunciation of Citizenship by Japanese Americans During World War II (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1985), 40–41; Michi Weglyn, Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps (New York: William Morrow & Co., 1976. Updated ed. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996), 160–61; Williams, American Sutra, 94.

10. To cite one example, Topaz’s Community Council put on a memorial service in November 1944 for nine Nisei from Topaz who had been killed in action in Europe six months after having refused to sanction such an event. Similarly, Rohwer’s Community Council—which was by this time almost entirely comprised of Issei—put on a memorial service on September 30, 1944 for five Nisei servicemen from Rohwer who had been killed in Italy. Similar services took place in almost every other camp. See E. W. Conrad, “First Community-Wide War Memorial Service at the WRA’s Central Utah Relocation Center, Topaz, Utah,” JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder H2.02:61; Summary of Monthly Reports [Rohwer], Month Ending September 30, 1944, p. 1, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder Q1.12:2; Rohwer Outpost, Sept. 30, 1944, 1.

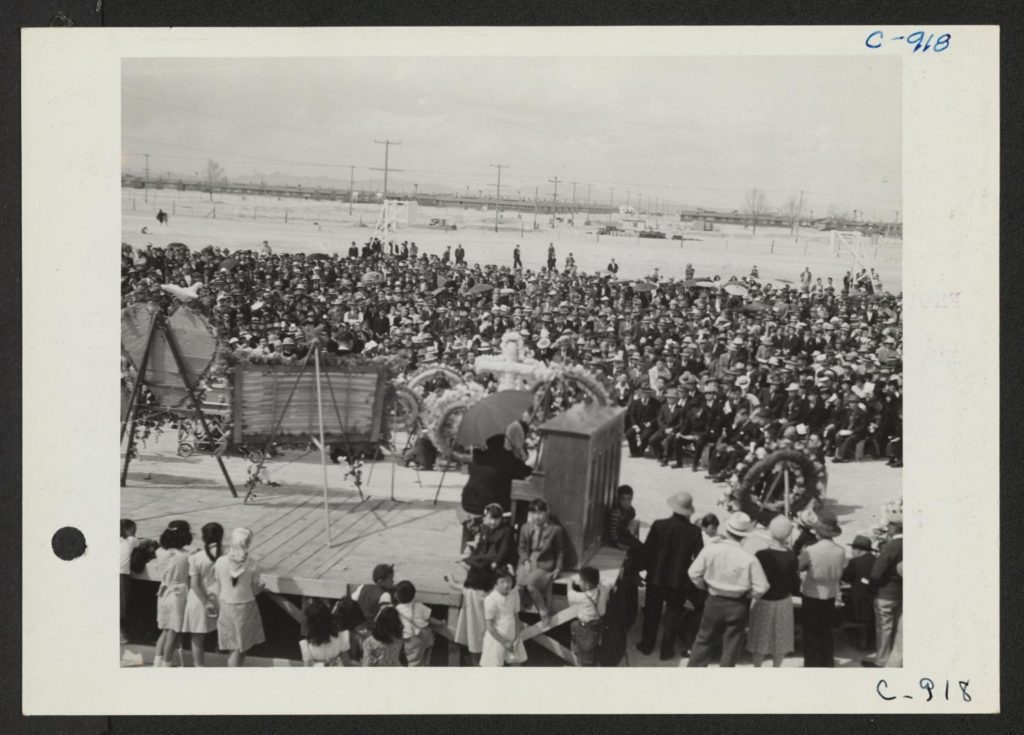

[Header: Mourners at a funeral service in Amache concentration camp. Courtesy of the Wada and Homma Family Collection.]