July 11, 2019

Two new documentaries break the mold of traditional cinematic takes on the World War II incarceration story. Densho Content Director Brian Niiya reviews the films—The Ito Sisters and Masters of Modern Design—and explains why you really ought to make time to watch them while they’re still available for free online viewing.

Though I can’t claim to have seen all of them, I suspect I may have seen more of the two hundred plus documentary films/videos that cover some aspect of the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans than anyone else. Generally, I find that the best of these were made years ago: titles like Emi, Who’s Going to Pay for These Donuts Anyway, Days of Waiting, and probably my single favorite, Family Gathering. Even the most recent of the “classic” titles, Conscience and the Constitution and Rabbit in the Moon, are around twenty years old now.

While there are certainly some more recent ones I can recommend, I find that many of the more recent productions share two major flaws: (1) So many are slight variations of what has already been done and use the same talking-heads-augmented-with-archival-images style (and often reuse the same limited number of archival video clips) that have been used so often before. So many also tackle the same narrow range of topics, or even if they do tackle a novel topic, don’t tell us anything new about it; and (2) As we get further removed from the wartime events, there are fewer and fewer people alive to interview about it. Thus, more recent videos have fewer and poorer quality interviews, often with people who can talk about camp only from the perspective of a child.

Two recent documentaries on the camp story that largely avoid these pitfalls recently aired nationally on PBS. Both are among the better recent documentaries, and they are also available online for a limited time.

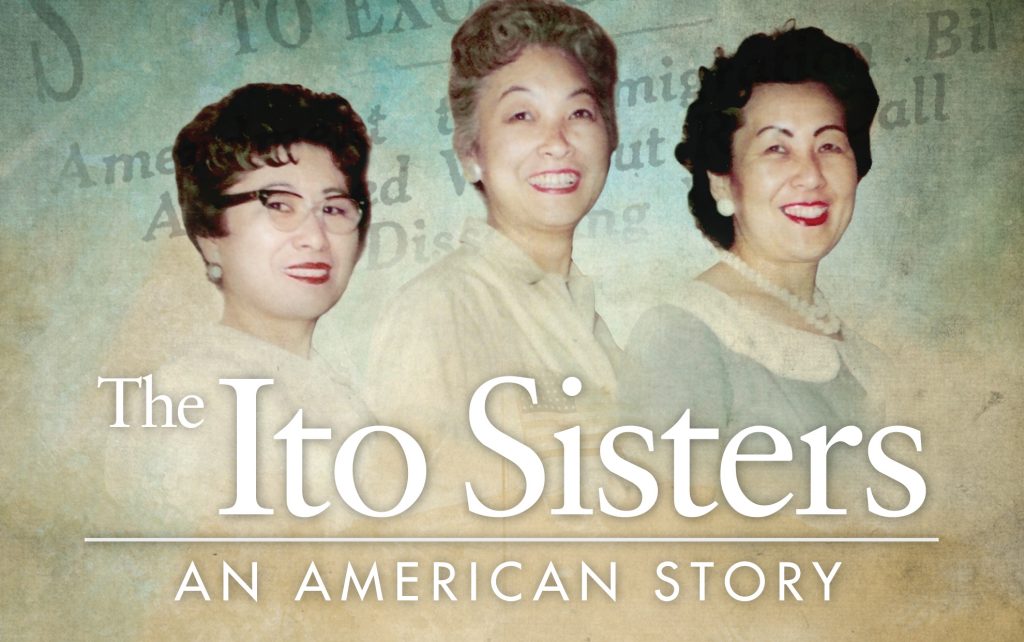

The Ito Sisters (2017) is on the surface a standard family saga focusing on three Nisei sisters whose lives span most of the 20th century. Family members—presumably including granddaughter and the film’s director, Antonia Grace Glenn—interview the three sisters, Nancy Ito Takahashi (b. 1914), Lillian Ito Nakano (b. 1916), and Hedy Ito Kadoi (b. 1922) over the course of many years, mostly in informal and group settings. So it is the rare recent film that includes previously unseen footage of interviews with older Nisei who recall the incarceration from an adult perspective.

Glenn uses illustrations by Manny Falcon Padua and animations by Carlos Bonilla and Kenny Navarro to augment the stories the sisters tell about their parents’ immigration, growing up on a farm outside of Sacramento, attending segregated schools, and the travails of the World War II years. Several Bay Area scholars—including Evelyn Nakano Glenn, the daughter of Lillian and mother of the filmmaker—provide additional historical context.

The Ito Sisters is also unusual in its woman-centered view of the story, with the interviewers teasing out stories of the Nisei women’s experience before and during the war that are often overlooked in other familial accounts. Thus, there are sensitive accounts of the two older sisters’ arranged marriages (and the unhappy nature of Nancy’s); childbirth, including the death of Nancy’s baby shortly after its birth as she arrived at Heart Mountain; sexual harassment; and Hedy’s romance with a soldier that her family forced her to break off. It is a much needed counterpoint to the generally male-centered themes of military service and resistance that are the focus of so many of the other camp narratives.

One flaw in The Ito Sisters is the relative neglect of the post-camp period. While telling the broader story of Japanese Americans after the war—the general difficulties of the return, the shift in public image, and the demise of alien land laws and the lifting of immigration and naturalization restrictions—there is little on the specific experiences of the sisters, and a lot of storylines are left hanging. The film ends with footage from Nancy’s 88th birthday party and with brief updates on the women’s postwar lives.

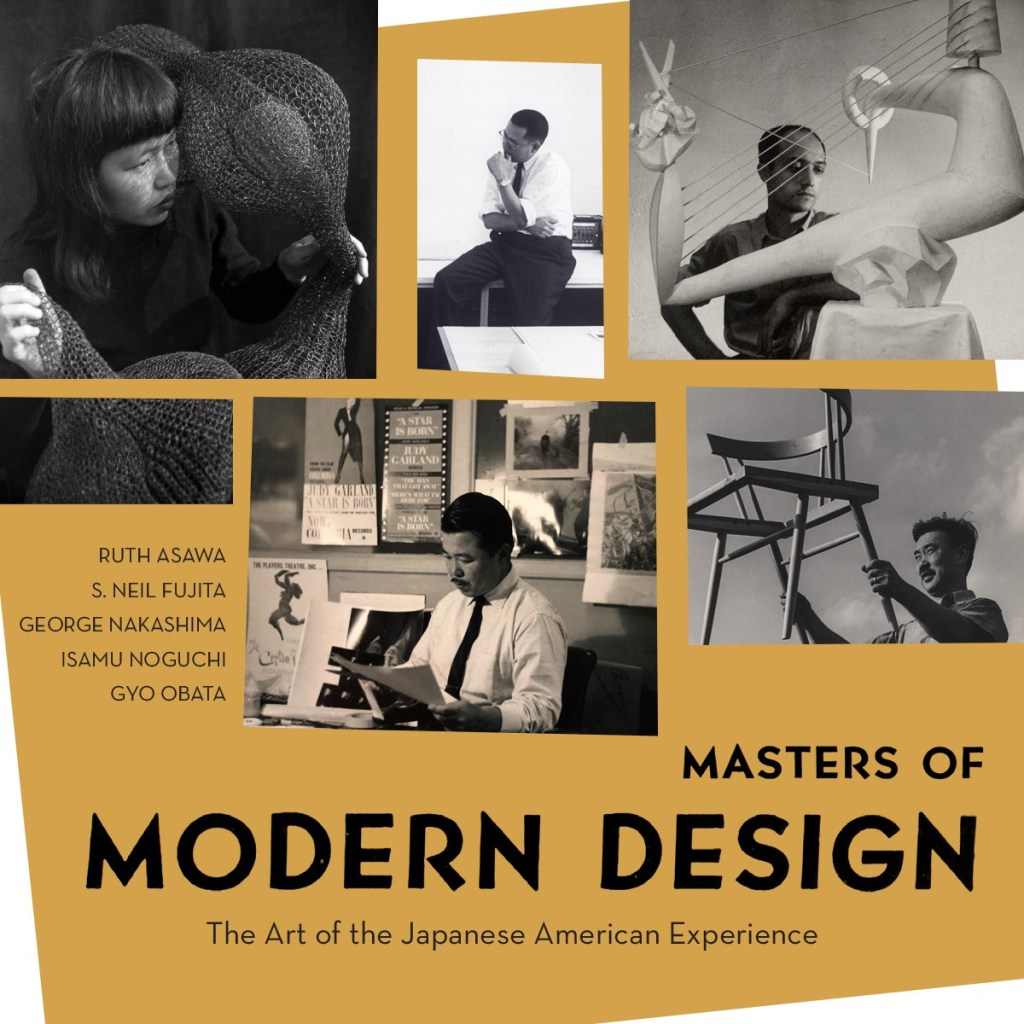

Masters of Modern Design: The Art of the Japanese American Experience (2019) tells the story of five artists whose work was influenced by their wartime incarceration. (Disclosure: Two of the film’s producers also serve as videographers on some of the Densho’s life history interviews; I am also briefly interviewed in the film.) The five—Ruth Asawa, S. Neil Fujita, George Nakashima, Isamu Noguchi, and Gyo Obata—all became well known figures in mid-century art and design, and the film does a good job of outlining their influence and highlighting their often striking work.

Though all but Obata have passed away, each was well known enough to leave behind a wealth of material used by the filmmakers in lieu of contemporary interviews, including earlier filmed interviews, archival footage of them working, and interviews with the many who can talk knowledgably about their lives and work.

A particular revelation are the children of the artists, many of whom carry on their parents’ legacies. Each is engaging and photogenic. And being visual artists, the works themselves are worth revisiting, ranging from the abstract designs of Fujita’s 1950s jazz album covers to Obata’s large scale architectural projects. The film does a good job of incorporating the wartime incarceration story and highlighting the impact of those years on the postwar directions their art ends up taking them. Also worth mentioning is the original cool jazz soundtrack by Dave Iwataki (who also did the music for The Ito Sisters) that adds greatly to the sense of time and place the film captures.

My one complaint about the film is the inclusion of Noguchi. He just doesn’t belong. While undoubtedly the most famous of the group in the mainstream world, he is fundamentally different from the others. He was a generation older than the others and already a well-known artist before camp, and though he was in camp, the circumstances under which he came to be in Poston were unusual and perhaps unique. While the others had lives that span the range of typical Nisei experiences, Noguchi’s was very different, and he did not in the main consider himself to be Japanese American. I couldn’t help but think of how much better the life and work of someone like George Tsutakawa or Kay Sekimachi—or perhaps even one of the Nisei artists from Hawaii who didn’t go to camp—would have fit into this story.

Masters of Modern Design is a co-production of the Frank Watase Media Arts Center of the Japanese American National Museum and KCET and was directed by Akira Boch.

Nonetheless, both The Ito Sisters and Masters of Modern Design tell stories about camp that depart from the standard narratives and are well made and visually interesting. Catch them online while you can!

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director