February 24, 2017

Rothstein earned the ire of Japanese Americans and scholars of WWII incarceration in 2011, when he criticized the newly-opened Heart Mountain Interpretive Center for its lack of “context”: other countries also interned enemy aliens during WWII, many Issei were “financially and ideologically devoted to the mother country and its policies,” the MAGIC cables, the Niihau Incident, Japanese submarines.

This latest piece largely recycles the same tired arguments Rothstein used back then. Once again, “loyalty to the emperor” and espionage and Niihau and submarines are cited as proof of “good reasons for West Coast wariness.” “Britain interned Jewish refugees from Germany as enemy aliens; Japanese Canadians were interned for longer than their American counterparts and lost all property rights.” As if not stooping to the level of imprisoning people fleeing the Nazis somehow absolves the United States of its own misconduct.

Much of his evidence is questionable and his phrasing deliberately provocative. (More on this in a moment.) But Rothstein’s larger point is largely true: that popular accounts of the incarceration downplay pro-Japan sentiments among Japanese Americans. While Rothstein is not entirely wrong in, a bit melodramatically, observing popular culture’s “tendency to see internment as a morality play in which the wholly innocent are wholly wronged,” he is very much mistaken when he claims that extensive accounts of Japanese nationalism among incarcerated Japanese Americans do not exist. In addition to the work of such historians as Yuji Ichioka and Brian Masaru Hayashi, Issei memoirs by Yasutaro Soga, Kumaji Furuya, and others reveal the pro-Japan sentiment among many internees (complicated by the fact that many of these same men had sons in the U.S. Army).

But the great leap of logic is to suggest that the presence of such sentiment justifies the mass imprisonment of the entire population. His comparison with German immigrants is instructive: thousands of German immigrants held pro-Nazi views, but these foreign nationals were treated as individuals, with only a tiny fraction of the 1.2 million people of German birth interned. Japanese Americans—whether immigrant or American citizen—were not afforded that same leniency.

Now let’s get back to that “evidence.”

“Noguchi alludes to Isei [sic, because apparently Rothstein can’t be bothered to learn how to spell the terms he writes about] as ‘potentially’ being ‘the most dangerous,’ with a ‘large subversive element among them’ that must be counteracted by encouraging ‘loyalty to America.'”

While there is certainly a grain of truth to what Noguchi says—Ichioka and other historians have documented a rise in Japanese nationalism among Issei and even some Nisei through the 1930s, much of it driven by the racism they faced in the U.S.—it’s disingenuous to present Noguchi as an expert on the subject. His observations were that of one man who was largely unfamiliar with the Japanese American community prior to his voluntary incarceration at Poston.

While there was undoubtedly some pro-Japan sentiment among Japanese Americans, having such sentiment and taking action are two very different things: despite being under surveillance by multiple investigative agencies for a solid decade prior to the war, little evidence of any actual danger posed by Japanese Americans turned up. Among those vouching for Japanese Americans were reports based on years of surveillance from the Office of Naval Intelligence and from a White House investigation led by FDR aide John Franklin Carter (the latter better known as the “Munson Report“). The Justice Department, Attorney General Francis Biddle, and FBI head J. Edgar Hoover also opposed mass removal and incarceration based on their own investigations.

“Japanese language schools taught loyalty to the emperor.”

It’s hard to prove a negative, but generally, no. Criticized and targeted with legislative action for decades by anti-Japanese agitators, Japanese language schools in California and Hawai’i were, by the 1920s, regulated by the state and required to emphasize American citizenship and loyalty. Their hours, textbooks, and curricula were all monitored by the state.

“In Hawaii, a Japanese couple tried to help a downed Japanese pilot escape just after the Pearl Harbor attack.”

This is a reference to the so-called Niihau Incident, which is a long and complicated story that could do with its own blog post, but even this brief sentence is off. It was one Nisei man—his wife played no role—and given that this took place on the isolated island of Niihau, there was no “escape” involved, although the man certainly helped the pilot. It is instructive to point out that the military leaders who ran Hawai’i under martial law—where the incident after all took place—opposed calls from Washington, D.C. to round up all Japanese Americans and thus no such mass incarceration took place there.

“Japanese submarines patrolled the West Coast; one shelled an oil field near Santa Barbara, Calif., on Feb. 23, 1942.”

There was such a shelling—and it did certainly feed into the fear felt by many at the time—but Rothstein fails to note that the attack did little actual damage and took place after Executive Order 9066. It played no role in the decision to force 120,000 Japanese Americans out of their homes.

“Decoded intercepts of Japanese cables suggested the presence of Japanese agents.”

A reference to the “MAGIC cables,” a set of intercepted and decoded Japanese diplomatic cables that have often been cited as evidence of Japanese American duplicity or sabotage since the redress movement. (Michele Malkin’s infamous “In Defense of Internment” relied heavily on this theory.) A few of these messages dealt with Japanese efforts to gather intelligence within the U.S. and the potential recruitment of Japanese Americans. Japanese consulates were authorized to enlist Nisei on the one hand, but advised against it and encouraged to pursue non-Japanese recruits at the same time.

The cables are at best ambiguous and at worst completely unreliable—but since they have some juicy passages, like the one quoted in Rothstein’s article, they are frequently dragged out by incarceration apologists. It’s also worth pointing out that of the 120,000 incarcerated, only a handful of Japanese Americans were ever found to have acted against the United States during World War II. And there is simply no justice in thousands of innocent people being stripped of their rights and liberties because of the actions of a few.

The work of Isamu Noguchi, Dorothea Lange, and others featured in these exhibits stand the test of time precisely because they give voice to the individuals affected by WWII incarceration. By moving beyond textbooks and government reports, we learn the human impacts of guilt by association.

As Densho Executive Director Tom Ikeda notes, “When determining guilt or innocence, judgement needs to be based on individuals, not on the race, religion, or country with which they identify. We did that with Japanese Americans during WWII and it was a mistake. At a moment when Muslims and immigrants are being vilified because of presumed association with criminals, it is essential that we remember the perils of that logic.”

Edward Rothstein is unable, or unwilling, to see the lessons offered by these artists—but we see, and we do not forget.

—

By Densho Special Projects Coordinator Nina Wallace and Densho Content Director Brian Niiya

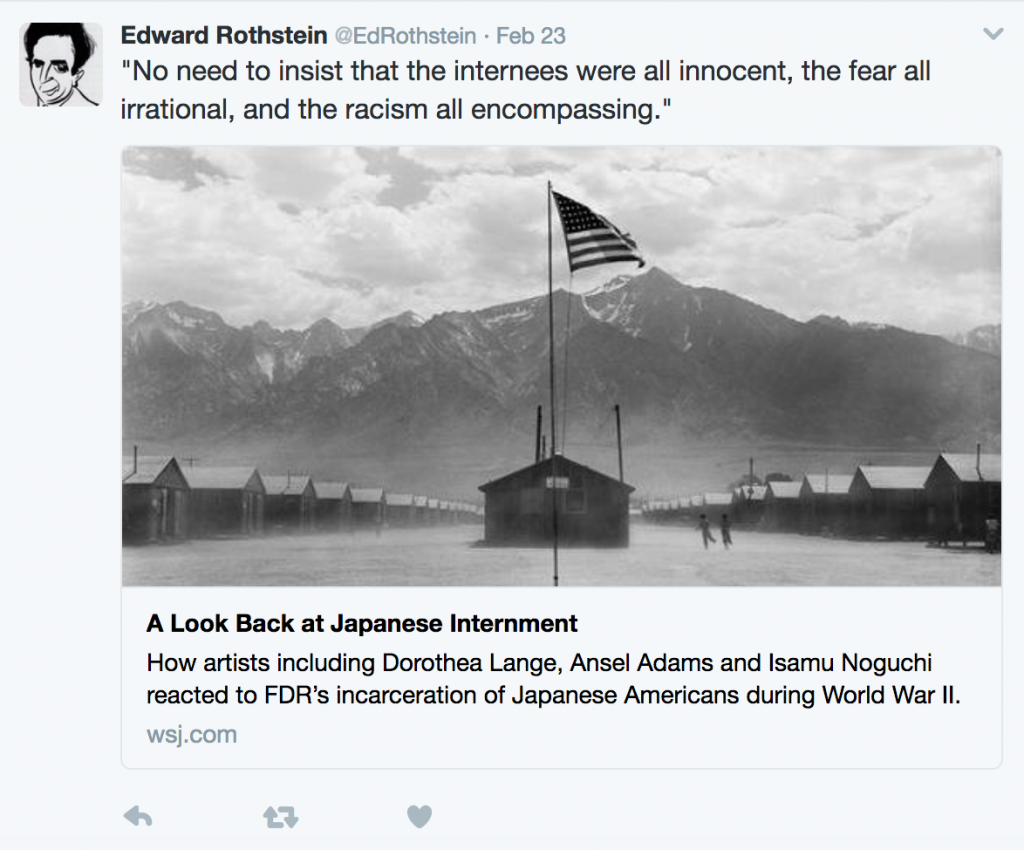

[Header photo, original Ansel Adams caption: Manzanar from Guard Tower, view west, (Sierra Nevada in Background) Manzanar Relocation Center, California. 1943. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.]