March 9, 2022

Densho Content Director Brian Niiya answers a question about vaccination efforts in WWII concentration camps from a survivor who experienced them firsthand.

Junko Mizuta writes:

With the vaccine mandates being implemented in many states, I recall when we were incarcerated in 1942, we had to get typhoid fever shots. All I remember is we had to get the shots because we did not know where we would be going, and just that thought of not knowing gave me a scary feeling. I can remember getting my shot and my arm being very sore — like today’s covid-19 vaccine shots! Did everyone get these shots or was it limited to the people in the Northwest? Does anyone remember this incident of standing in line for shots? I can’t even remember where we had to go to get the shots. Anyone else remember any of this or has anyone ever made any comments in their oral histories on the shots?

Indeed, the current discourse over vaccines does in some ways recall the typhoid and smallpox vaccination efforts that mostly took place in the “assembly centers” that held forcibly removed Japanese Americans in the spring and summer of 1942. As noted in the government’s Final Report, Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942, “virtually all” Japanese Americans in the “assembly centers” were vaccinated, though interestingly, vaccination doesn’t seem to have been mandated, as the report notes several categories of people who did not get the shots, including “those individuals refusing absolutely.” But there were also community based efforts to secure vaccinations prior to the roundup, as well as vaccinations administered in the enemy alien internment camps and in the War Relocation Authority concentration camps.1

But to start with Ms. Mizuta’s last question, the typhoid shots in particular—which were administered in three courses and which seemed to have significant side effects for most—are a well remembered part of camp lore, noted in many contemporaneous and retrospective accounts of camp life. Accounts appear in many Densho oral histories. “Those shots really hurt,” remembered Hiro Heidi Inahara, who was fourteen at the time. “And when I came back through the hallway, I fainted. And when I woke up, I was still on the floor.” Chizu Omori, age twelve, remembered the shots administered at Poston as “just awful” and being “sick after each one. In that heat and everything, that was really terrible.” Seven year old Shigeo Kihara recalled being literally knocked off his feet by the vaccine and having to crawl back to his barrack. Ted Hamachi, age 15, recalled that the shots were “done by blunt needles and sterilized with … a alcohol flame.”2

But it seems that even at the time, the shots were recognized as significant milestones. The final issue of the Tanforan Totalizer includes a section that recalls the history of that camp and notes “[t]he typhoid and smallpox shots that periodically inflated Center biceps and left half the residents wistfully wishing that someone would somehow put them out of their misery.” Pacific Citizen columnist Bill Hosokawa devoted his July 9, 1942 “From the Frying Pan” column to the shots, noting that every inmate “in the not distant past has experienced the dubious pleasure of a series of anti-typhoid injections” and that while ”[s]ome come through the ordeal without so much as a swelling,… even the strongest of men may be confined to bed for a day or two with chills, fever, backache and headache. Miné Okubo’s classic 1946 graphic novel Citizen 13660 also recalls “groans in the stable” from the shots.3

Contemporaneous assembly center records indicate that the shots were pretty routine from the administration perspective, as none of the camps reported any sort of major problems or unrest, and all apparently succeeded in vaccinating the vast majority of their inmates. But as with much of the early assembly center experience, the vaccinations were also disorganized, chaotic, and unpleasant from the inmate perspective. Nisei Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) fieldworkers reported on the vaccinations at the Tanforan site. “The set-up for giving shots in mass is really lousy,” wrote Tamotsu Shibutani in his May 6, 1942 diary entry:

“It was really a sad excuse for a clinic. There are not enough doctors around here, and they had dentists, optometrists, and others substituting for the M.D.’s. One woman in our barrack had a needle broken in her arm; another woman had to shout in agony because the ‘Doctor’ bent the needle after it entered her arm.”

In a later report, Shibutani, Haruo Najima, and Tomika Shibutani reported that the vaccination lines stretched as long as 200 yards. “The conditions were atrocious,” they wrote. “After waiting for over an hour in line while the wind and the dust gush all over the waiters (sic) one finds that in the mass production many mistakes are made—needles broken, an overdose given, and several other mishaps occur.” Fred Hoshiyama called the vaccination set-up “pathetic,” citing the long lines and “volunteer helpers” who “injected [shots] amateurishly into veins.” In a similar vein, Y. Fred Fujikawa, a physician at the Santa Anita detention site, called the vaccinations “the worst experience I had at Santa Anita,” citing an ambulance that was “busy day and night bring[ing] in the people who were sick” after getting the shots and seeing “some of them faint in the line.”4

Though the vast majority of inmates had already been vaccinated by the time they arrived at the WRA camps, there still needed to be vaccination programs at some of the camps, since there were thousands of inmates who came directly to them without having gone through an “assembly center.” Many came from the “white zone”—the eastern part of California where the army had initially ruled that Nikkei didn’t need to be removed before changing its mind—and were sent to Poston, Tule Lake, and Gila River. Thus there were large-scale vaccination programs at those camps. At Poston, a “typhoid survey” was taken in Unit III, where most of the “white zone” inmates were held, starting at the end of August.5

In addition to the vaccination programs in the various confinement sites, there were also some community immunization efforts set up before the round up, in anticipation of mass removal and confinement in tight quarters. These programs were fueled by rumors—including of a typhoid epidemic at Manzanar—and fears of the unknown at the “assembly centers.”

Kikuo H. Taira, a young Nisei doctor in Fresno, set up an immunization program prior to removal. “I could think of nothing worse than to go to a strange place and get a typhoid shot and get fever and have to be laid out for a day or two,” he said in a 1980 interview. “And knowing where the assembly center was going to be, I thought that would be a hell of a place to get your shots.” Taira and other doctors got permission from the local health department and vaccinated Japanese Americans in the area.

Mitsuo Paul Suzuki, a physician, and Nobu Suzuki, a social welfare worker, set up a similar program in Seattle, administering hundreds of shots prior to the removal of Seattle Nikkei to Puyallup. In a 1998 Densho interview, Nobu recalled their vaccination requests being rejected by the city health department, but being aided by the Cannery Workers Union: “So we set up [at the] cannery workers’ office building, and bought the medicine and gave the shot.”6

Various Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) chapters also set up vaccination programs, including in the Placer and Reedly areas. But as with seemingly everything associated with the JACL during this time period, a program in Sacramento led to conflict that spilled over to the assembly center and eventually to Tule Lake. Fearful of assembly center conditions, many Nikkei in Sacramento sought out typhoid shots from private doctors, who charged substantial fees for the shots. A prominent Issei doctor closely tied to the local JACL and influential with the local medical establishment charged even higher fees than other doctors. Seeing the situation, a group of Nisei doctors sought to pool resources to purchase serum from the city health department and administer low cost vaccinations to the community. But the Issei doctor, wanting to retain his lucrative vaccination fees, reportedly opposed this plan and used his influence to implore the health department to close down the vaccine clinic. When word of his actions got out, anger rose against the doctor, and he eventually agreed to cooperate with the mass vaccination program. The vaccinations were ultimately administered at the Sacramento Buddhist Church.7

Though information is sparse, there were apparently similar vaccination efforts in the camps run by the army or INS to hold Issei arrested after the attack on Pearl Harbor. In her Ph.D. dissertation, Akiko Nomura writes about Toranosuke Fujimoto, an Issei man from Riverside, California, who was interned at Tuna Canyon and Santa Fe before being “paroled” to Poston in July 1942. His accounts of typhoid vaccinations at Santa Fe in May 1942 sound similar to accounts from assembly center inmates in terms of significant side effects: “I have pains all over my body and dizzy. I could neither eat breakfast nor talk to others.” He reports that all of the internees there were given the shots in alphabetical order starting on May 4 with the subsequent shots coming one and two weeks later.

In his internment memoir, Honolulu businessman Kumaji Furuya reports on getting the first vaccine at the INS detention station in Honolulu, then the second on the ship from Hawai`i taking him and other internees to mainland detention camps. Echoing some of the assembly center accounts, Furuya observes one man who had a needle “inserted by the apparently inexperienced corpsman” break in his arm, requiring removal of the needle and another shot. Honolulu journalist Yasutaro Soga, who was also among the Hawai`i Issei interned on the continent, describes vaccination taking place as the Issei men were being released from internment, with those leaving for Japan on the M.S. Gripsholm getting their shots starting in August 1943 and with Soga himself getting the shots in June and July 1945, as the end of the war and a potential return to Hawai`i approach.8

There are at least a couple of clear parallels between these accounts of vaccination then and now. Though I couldn’t find any detailed documentation, there is mention here and there of “immunization cards” and the like much like today that attempt to keep track of who has and has not been vaccinated. There seemed to also be some level of resistance, as the passage from the Final Report above indicates. In their study of medical care in the WRA camps, Naomi Hirahara and Gwenn M. Jensen tell a story of a group of Kibei who resisted reminders to get the shot from Dr. Yoshiye Togasaki, the Nisei doctor who headed the vaccination efforts at Manzanar. “She told them that if they didn’t show up, she was going to get the ambulance to bring them up there,” remembered her aide, Toshi Yamamoto. “‘Oh no you’re not,’ the internees retorted.” In diary passages that read almost comically today, Charles Kikuchi details delaying his shots as long as possible while at Tanforan. While his family gets the shots in May, Kikichi first cites a lack of confidence in the medical personnel as a reason to wait, then delays further when he finds long lines for the shots in July. Later that month, he writes, “Chas, you are a coward!” Finally, he is cornered in his barrack by a camp doctor in August and has no way to save face but to finally get the shot. The doctor tells him that “a lot of the residents refused to take the shots for this reason [too forceful medical staff attitudes], plus all the rumors going around about how ill people got.” His vaccination is otherwise uneventful.

Like many aspects of ordinary life in the concentration camps, the vaccination program was a microcosm of larger trends—early administrative ineptitude that led to inmate suffering, adaptations, and resistance, among them—as well a window into the past that serves as an interesting counterpoint to the pandemic that’s currently dominating our collective experience.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

References

1. John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 193.

2. Hiro Heidi Inahara Interview by Betty Jean Harry, Segment 5, Portland, Oregon, July 2, 2014, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Archive; Chizuko Omori Interview I by Martha Nakagawa, Segment 5, Emeryville, California, March 14, 2011, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Archive; Shigeo Kihara Interview by Richard Potashin, Segment 13, Sacramento, California, April 1, 2011, Manzanar National Historic Site Collection, Densho Digital Archive; Ted Hamachi Interview by Kirk Peterson, Segment 10, West Covina, California, March 4, 2010, Manzanar National Historic Site Collection, Densho Digital Archive.

3. Tanforan Totalizer, Sept. 12, 1942; Bill Hosokawa, “Reflections on Anti-Typhoid Shots,” Pacific Citizen, July 9, 1942, 4; Miné Okubo, Citizen 13660 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1946; introduction by Christine Hong, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014), 54.

4. Tamotsu Shibutani diary, May 6, 1942, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records, Bancroft Library at the University of California at Berkeley (JAERR subsequently), BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder R 21.00:1**; Tamotsu Shibutani, Haruo Najima, Tomika Shibutani, “The First Month at Tanforan: A Preliminary Report,” JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B8.31; Letters, Fred Hoshiyama to Deki and to Verlin, May 21, 1942, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B12.41; Gwenn M. Jensen, “The Experience of Injustice: Health Consequences of the Japanese American Internment” (Doctoral Dissertation, University of Colorado at Boulder, 1997), 253–54.

5. Charles Kikuchi diary, May 19 and 26, 1942, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder W 1.80:01**; Eleanor Jones Shirrell diary, May 30, 1942, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder R 25.10:1**; Poston Press Bulletin, Aug. 29, 1942, 1.

6. Tamotsu Shibutani, “The Initial Impact of the War on the Japanese Communities in the San Francisco Bay Region,” JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder A17.04; Kikuo H. Taira oral history by Yoshino Hasegawa, May 28, 1980, “Success Through Perseverance,” California State University Fresno, California State University Japanese American Digitization Project; Jensen, “The Experience of Injustice,” 253; Louis Fiset, Camp Harmony: Seattle’s Japanese Americans and the Puyallup Assembly Center (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 70–71; Nobu Suzuki Interview II by Dee Goto, Segment 19, Seattle, Washington, June 11, 1998, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Archive.

7. Pacific Citizen, July 2, 1942, 7, and July 30, 1942, 8; Shotaro Frank Miyamoto, “Chapter I: Introduction,” The Tule Lake Report, Nov. 30, 1944, pp. 49–52, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder R 20.65:1; Naomi Hirahara and Gwenn M. Jensen, Silent Scars of Healing Hands: Oral Histories of Japanese America Doctors in World War II Detention Camps (Fullerton, Calif.: Center for Oral and Public History, California State University, 2004), 32.

8. Akiko Nomura, “Fujimoto Diaries 1941–1946: Japanese American Community in Riverside, California, and Toranosuke Fujimoto’s National Loyalties to Japan and the United States during the Wartime Internment” (Ph.D dissertation, University of California, Riverside, 2010), 263–65; Suikei Furuya, An Internment Odyssey: Haisho Tenten (translated by Tatsumi Hayashi, foreword by Gary Y. Okihiro, introduction by Brian Niiya and Sheila Chun; Honolulu: Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai’i, 2017), 45; Yasutaro [Keiho] Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire: The World War II Internment Memoirs of a Hawai’i Issei (translated by Kihei Hirai; Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008), 132, 192.

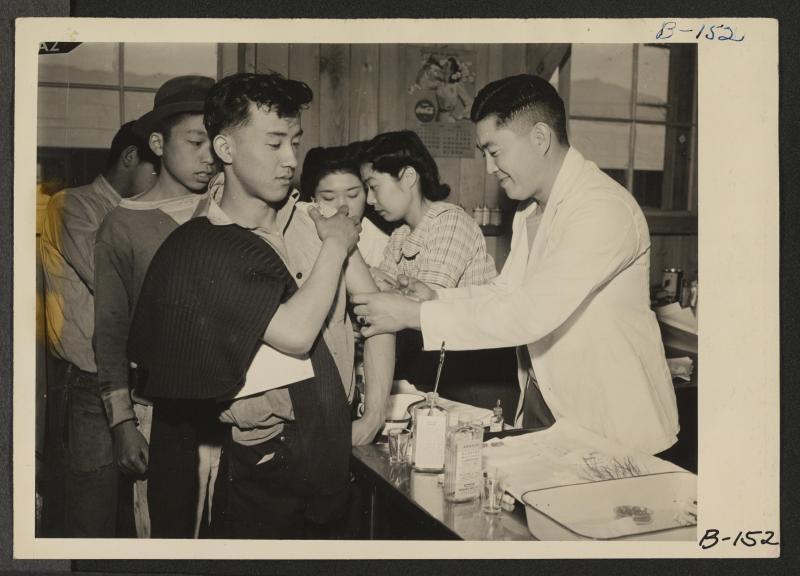

[Header: Japanese Americans receiving typhoid vaccinations while registering for forced removal in San Francisco, April 20, 1942. Photo by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]