March 5, 2024

Growing up I was always fascinated by the blue trunk in our sunroom. When opened, it reeked of mothballs but contained all the treasures my grandmother saved over the course of her life. There were photographs, Japanese dolls, kimono of different colors, and a tiny silk dress my aunt wore as a toddler. But the most beautiful item was my grandmother’s wedding obi. This obi traveled across the Pacific Ocean from Japan to Washington State. It survived the purge of Japanese cultural objects when my grandparents were forcibly removed to the incarceration camps in World War II. And it stayed with them through all their life events in Seattle after the war. It remains a cherished heirloom in our family even today.

Shizuko Kikuchi

My grandmother, Shizuko (Kikuchi) Oiye, was kibei, an American citizen by birth who received her education in Japan. She was born on November 14, 1922 in Brighton, Colorado to Chokichi and Torae (Seike) Kikuchi.1 The Kikuchi family established themselves as successful farmers and Shizuko grew up like any American farmer’s daughter, playing near the fields, tending vegetable gardens, and going to the local school. Despite their success in Colorado, Chokichi felt the pull of familial responsibility and moved his entire family to back Japan in 1932.2

Growing up as an American in Colorado, Shizuko still experienced the traditions and values of Japan through her parents, other immigrant Japanese families, and the Japanese language school. But it must have been a shock to leave everyone and everything she knew in the United States and resettle in Japan. Over the next 8 years, Shizuko adapted to life in Japan, graduated from high school, and worked for a short stint at a bank. And as expected in a culture deeply based in the family unit, she married Shigenori Oiye when she was only 18 years old.3

An Arranged Marriage

Shizuko and Shigenori married at a time when the ie or household system dominated in Japan. According to this system, the eldest son was responsible for the social and economic well-being of everyone living under his household, including parents, spouses, children, and siblings.4 This was considered particularly important in the years leading up and during to World War II when “the government re-emphasized the virtue of the ie system by claiming strong family unions to be the basis of a nation ruled by the emperor, the head of all families.”5 During this time, almost all marriages were either arranged or approved of by the head of household.6

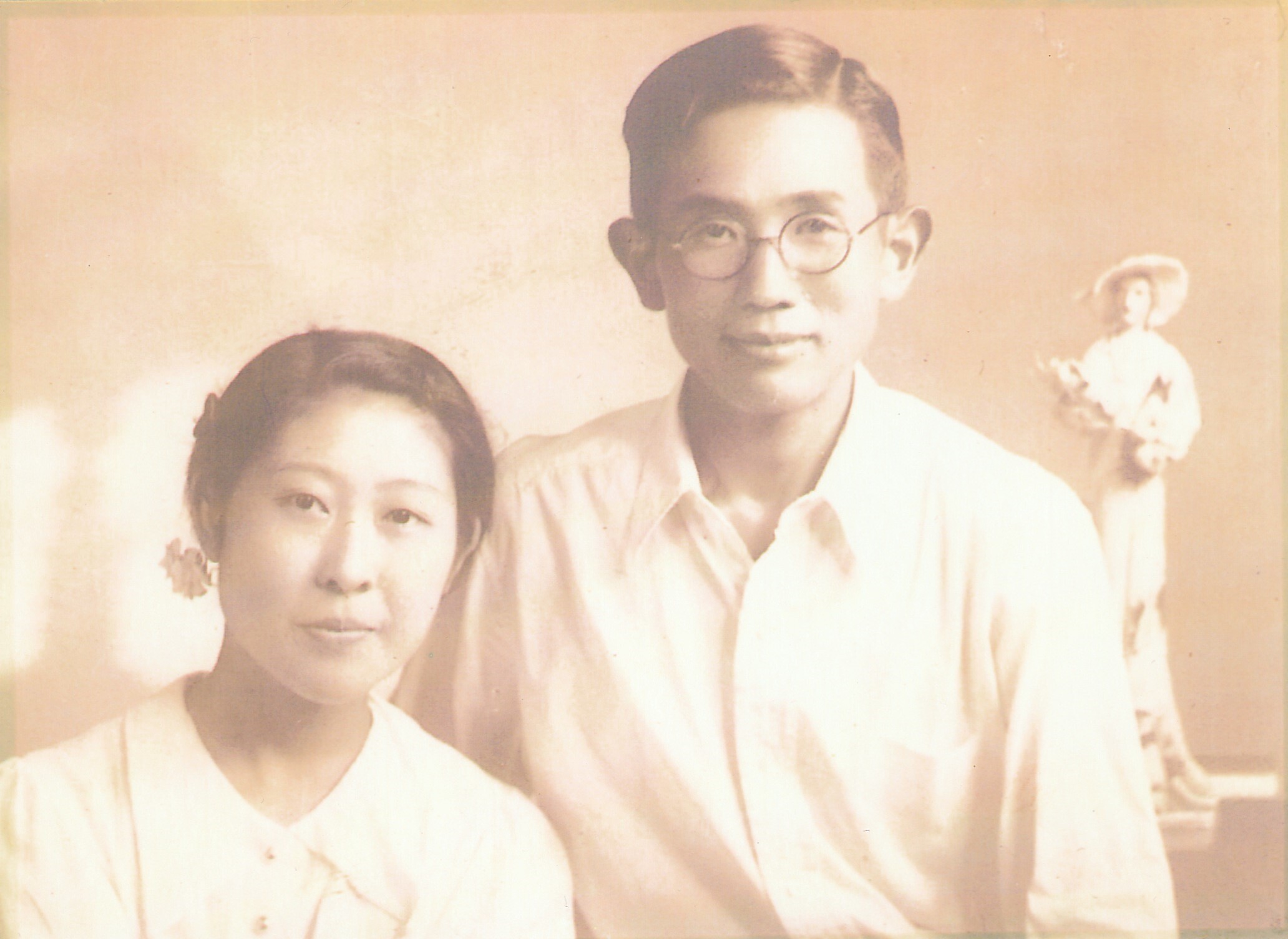

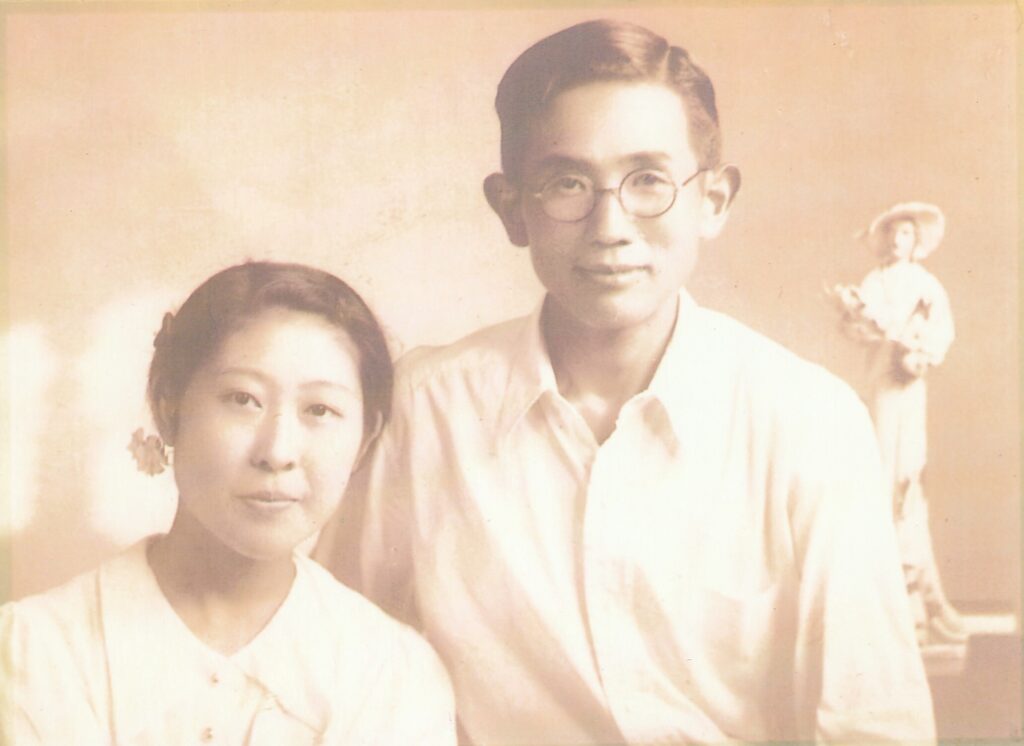

With this emphasis on arranged marriages, it does not seem that Shizuko and Shigenori’s union was a love match. In her autobiography she glosses over her wedding with just one brief sentence noting: “in [sic] June 8th [1940] got married to Shigenori Oiye, lived with his parents until we left in September and came to US.”7 No mention of how she felt about it or the ceremony that must have taken place. We do know Shizuko wore a traditional wedding kimono and the obi that became a family heirloom.

Traditional Japanese Wedding Dress

Kimono are traditional Japanese garments that have been worn in Japan for centuries. They can be casual or formal, worn by men and women, and are made in a multitude of colors, designs, and fabrics. The obi is a belt which is wrapped around the waist, originally to keep the kimono closed but more recently as a decorative accessory. As with kimono they are made from a wide variety of fabrics, colors, and designs. The types of kimono and obi and how they are worn convey different types of symbolism.

Shizuko’s wedding obi is over 160 inches long and weighs almost 5 lbs. Just picking it up today it is hard to imagine wearing something that heavy. It is a maru obi, “the most formal and regal of obi” which are rarely worn except by geisha and brides.8 And the fabric is called kinran, a high-quality gold brocade with a decorative design that includes colorful cranes and oshidori (mandarin ducks), both symbols of a couple’s union and love.

Unfortunately, Shizuko’s wedding kimono did not survive and there are no known photos of her and Shigenori on that day. But looking at the obi I can imagine what it was like, the formality of the occasion, the ceremonial dress, and her nerves as an 18-year-old girl marrying an almost stranger, knowing she was leaving her family to start her newlywed life in the United States.

Returning to the United States

Like Shizuko, Shigenori Oiye was kibei, an American citizen born in Tacoma, Washington who returned to Japan for his primary and secondary education. The Oiye family had owned and operated cafes in Tacoma since the late 1890s and in the 1930s and 1940s Shigenori helped his half-brother, Tsunetaro Oiye, run the Owl Café at 1336 Pacific Ave.9 It was expected that Shizuko would follow her husband back to Tacoma and help with the business, So, once again she had to leave what she knew behind and travel to an unknown place where she had few connections other than her new husband’s family.

Although they had been married in Japan on June 8, 1940, Shizuko and Shigenori sailed on the Yawata Maru as though they were unmarried: both single, a student and a waiter.10 Shizuko stayed in a cabin with two other women, a Japanese Canadian and a Russian, while Shigenori was in a different, likely all male, cabin.11 The wedding obi could have been among the items she packed for this trip across the Pacific Ocean, a valuable heirloom and reminder of the family she left behind.

The reason for their unmarried status upon arriving in Seattle, Washington remains unclear. Perhaps, as American citizens, their marriage in Japan was only ceremonial and they had to legally marry in the United States, which they did on April 14, 1941. Their official marriage happened at the Justice of the Peace in Tacoma with two witnesses they likely didn’t know, L.A. Parshall and Ethel Y. Carlson.12 Shizuko and Shigenori had friends and family in the area, so these two non-Japanese witnesses seem to imply the marriage ceremony was transactional, not an event to be celebrated. In fact, they had been back in Tacoma for almost 7 months before visiting the Justice of the Peace, arriving in Seattle in September 1940 but not legally marrying until April 1941. Their first child, Misa would be born in November 1941, perhaps providing the impetus to finally make the marriage legal in the United States.13

World War II Incarceration at Tule Lake

The December 7, 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor, followed closely by Executive Order 9066, upended Shizuko’s and Shigenori’s life in Tacoma.14 On May 17, 1942 they and all other Japanese Americans living in Tacoma were forcibly removed to Pinedale Assembly Center near Fresno, California. They would quickly be moved to a more permanent incarceration camp at Tule Lake where they remained until the end of the war.15

In the months between Pearl Harbor and forced removal, Japanese American families lived in a limbo of fear and uncertainty. They struggled with what to keep and what to destroy and there was a fear that anything too Japanese would make people targets of the FBI.16 When exclusion orders were finally released, Japanese Americans were informed they would need to pack bedding, toiletries, extra clothes, dining utensils, and person effects but that “the size and number of packages is limited to that which can be carried by the individual or family group.”17 This essentially amounted to two suitcases per person. Everything else had to be sold or stored with friends and neighbors, not all of whom turned out to be trustworthy. How did Shizuko and Shigenori decide what to take when they had almost no information about where they were going or how long they would be gone?

It is truly a miracle that the wedding obi survived the incarceration period. It could easily have fallen under the umbrella something too foreign, too non-American or been stolen while in storage. Ultimately, we do not know how the obi made it through the war. Perhaps Shizuko decided its value was so high that it deserved a place in a suitcase. Or perhaps they have a trustworthy friend who protected in until Shizuko could retrieve it during or after the war. When Shizuko and Shigenori left Tule Lake on February 27, 1946 they left with 15 cases, making it possible they retrieved the obi while in camp.18 However it happened, the obi made it through the war safely.

Post-War Resettlement

Shizuko and Shigenori were among the last Japanese Americans to leave camp. Early on they had both signed no to questions 27 and 28 on the so-called “loyalty questionnaire” which resulted in their continued segregation at Tule Lake for being Japan sympathizers.19 So they stayed in Tule Lake until February 1946, leaving just one month before the entire camp closed.20

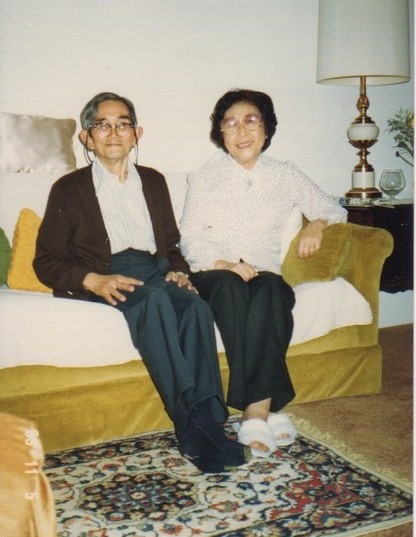

Instead of returning to Tacoma, Shizuko and Shigenori settled in Seattle. They would live the rest of their lives there, raising three children, working in laundries and restaurants, and trying to forget the incarceration.

Today, four generations of Oiyes have grown up in Seattle and Shizuko’s obi is still with us. It is a reminder of her and the many trials and joys she experienced in her life, from Colorado to Japan, Tacoma to Tule Lake, and finally to Seattle. The obi links us to our Japanese ancestors even when our ties to them have stretched thin.

—

By Caitlin Oiye Coon, Densho Archives Director

This article was originally published in The Journal of the Seattle Genealogical Society, Vol. 72, No. 2, Fall 2023.

Make a gift to Densho to support the Catalyst!

References

- All websites consulted on 28 June 2023.

. Yawatahama City, Ehime Prefecture, koseki [family register], Chokichi Kikuchi [長吉 菊池] household, registered domicile 682 Yano machi Oaza, translated by Naoko Tanabe; Yawatahama City Hall, Ehime Prefecture, Japan, no. 630754; certified copy held by Caitlin Oiye Coon, 11204 127th Ave NE, Kirkland, WA 98033. ↩︎ - Shizuko (Kikuchi) Oiye, autobiography, abt. 1990; certified copy held by Caitlin Oiye Coon. ↩︎

- Oiye, autobiography, abt. 1990. ↩︎

- Satoshi Sakata, “Historical Origin of the Japanese Ie System,” (n.d.), Chuo Online (https://yab.yomiuri.co.jp/adv/chuo/dy/opinion/20130128.html), “What Is Ie?, para. 3.. ↩︎

- Junko Takahashi, “Century of Change: Marriage sheds its traditional shackles,” Japan Times (Tokyo), 13 December 1999, (https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/1999/12/13/national/century-of-change-marriage-sheds-its-traditional-shackles/). ↩︎

- Anne E. Imamura, “Marriage in Japan: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow,” Education about Asia 13:1, Spring 2008 (https://www.asianstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/marriage-in-japan-yesterday-today-and-tomorrow.pdf), p. 25. ↩︎

- Oiye, autobiography, abt. 1990. ↩︎

- “Kimono and Obi,” Rinne Kimono, n.d. (https://www.rinnekimonos.com/kimono-and-obi). ↩︎

- “Washington, U.S., County Birth Records, 1870-1935,” Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1209 : accessed 22 Feb. 2023) > Washington State Department of Health > Washington State Department of Health Birth Index: Reel 4 1939 > image 1106; Department of Health, birth index, Shigenori Oiye, 8 Mar. 1911. And United States, Department of the Interior, War Relocation Authority, evacuee case file for Shigenori Oiye, individual no. 19446A, p. 22; National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the War Relocation Authority, Record Group 210, 18W3, box 4806, 8/23/4; held privately by Caitlin Oiye Coon. ↩︎

- “Washington, Seattle, Passenger Lists, 1890–1957,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-G5NS-J6J : downloaded 7 Mar 2023), digital film 4878221, images 363–4, entry for Shigenori Oiye and Shizuko Kikuchi, arriving Seattle, Washington, aboard S.S. Yawata Maru, 11 Sept 1940. ↩︎

- Oiye, autobiography, abt. 1990. ↩︎

- “Washington, County Marriages, 1855–2008,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89NB-VH2B : viewed 13 July 2022), digital film 4233774, image 195, Pierce Co., Marriage Certificates vol. 46, no. 70105, Oiye-Kikuchi, 17 April 1941. ↩︎

- And U.S., Dept. of the Interior, WRA, evacuee case file for Shigenori Oiye, individual no. 19446A. ↩︎

- Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on 19 February 1942 which allowed the secretary of war and military commanders to prescribe military zones from which people could be excluded. Although it did not explicitly name Japanese Americans it resulted in the forced removal of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. Brian Niiya, “Executive Order 9066,” Densho Encyclopedia, 24 February 2020 (https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Executive_Order_9066/). ↩︎

- U.S., Dept. of the Interior, WRA, evacuee case file for Shigenori Oiye, individual no. 19446A. ↩︎

- Alice Ito, interviewer, Betty Morita Shibayama Interview Segment 11, Seattle, Washington, 27 October 2003, Densho (https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-densho-1000-152-11). ↩︎

- United States, Wartime Civil Control Administration, Instructions to All Persons of Japanese Ancestry, C.E. Order 20, 24 April 1942; Densho (https://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-352-163), p. 2. ↩︎

- “United States, War Relocation Authority centers, final accountability rosters, 1942–1946,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9RF-59SQ-Y : downloaded 7 Mar 2023), digital film 101044949, image 366, War Relocation Authority, Final Accountability Roster of the Tule Lake Relocation Center, vol. I, 1946, entry for Oiye, family no. 19446. And U.S., Dept. of the Interior, WRA, evacuee case file for Shigenori Oiye, individual no. 19446A. ↩︎

- To learn more about the “loyalty questionnaire” and questions 27 and 28 visit the Densho Encyclopedia (https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Questions_27_and_28/). ↩︎

- U.S., Dept. of the Interior, WRA, evacuee case file for Shigenori Oiye, individual no. 19446A. ↩︎