November 14, 2022

I’ve always thought of myself as a somewhat atypical Sansei in various ways, chief among them, that one of my Nisei parents—my mother in this case—was a bit more “Japanesy” because her family had spent significant time in Japan before, during, and after the war. As a result, I’ve had multiple relatives in Japan that I’ve kept in touch with, including my mother’s eldest brother, a Nisei born and raised in Hawai`i, who was involuntarily conscripted into the Japanese army during World War II, lost his US citizenship as a result, and lived out his life in Japan, where his “Sansei” children—my cousins—are Japanese.

My wife is sort of like this too, since she has two uncles who were Tule Lake dissidents who renounced their American citizenships and went to Japan after the war. She too, has “Sansei” cousins who are Japanese. Oh, and one of her mother’s cousins, a Nisei girl born and raised in Tacoma, Washington got sent back to Japan to care for a grandmother in 1937 and never came back to the US. Her Japanese “Sansei” (do we need to invent a word for this population, since I’ve already referred to it three times?) daughter has become a renowned scholar of worldwide peace museums.

Many of my Sansei Japanese American studies friends and colleagues—a disproportionately high number it seems—have parents that were classic Kibei (Nisei sent as children to be raised by relatives in Japan for a combination of economic and cultural reasons), while I know others who have parents born in Manchuria or other outposts of the Japanese empire, had gone to college in Japan prior to the war, or who were hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors).

Which raises the question: could it be that we’re not really atypical?

Two new books—Michael R. Jin’s Citizens, Immigrants, and the Stateless: A Japanese American Diaspora in the Pacific and A. Carly Buxton’s Unthinking Collaboration: American Nisei in Transwar Japan—definitively answer that question in the affirmative. (Disclosure: Jin is a contributor to the Densho Encyclopedia.) Jin writes that some 50,000 Nisei—about a quarter of the total—spent significant time in Japan or the Japanese empire before the war, and the two authors peg the number of Nisei in Japan during the war as between 20,000 and 35,000. Together, Jin and Buxton make a persuasive case that these Nisei stories—and thus my family story—are not unusual or extraordinary cases, but part and parcel of the full Nisei experience, albeit a part that has often been suppressed.

The two authors take different and complementary approaches, with their titles being indicative of their differences. Drawing on a broad range of both Japanese and English language sources, Jin takes a broad and fairly straightforward overview of the topic devoting two chapters to Nisei in prewar Japan, two on Kibei in the US during the wartime incarceration, and two on Nisei caught in Japan during the war. Buxton’s approach is narrower and more theoretical with a focus on the last group, in particular the seeming contradiction of their lives as subjects of the Japanese empire during the war and as Americans during the US occupation of Japan immediately after.

Jin’s prewar chapters encompass not only the classic Kibei group but other groups as well, including Nisei who moved to Japan or the Japanese empire with their entire families, their Issei parents having grown disillusioned with the racism they faced in the US, or Nisei young adults in the 1930s who traveled to Japan on their own for further education or to work at jobs that seemed to provide better opportunities than the sort of jobs they were limited to in the US. Jin describes the special schools and programs that targeted this Nisei group and also notes Nisei football players and jazz singers who gained some measure of fame in Japan, trading on their American identity. Jin also delves into the cases of Nisei women who married Japanese nationals—and thus lost their American citizenship due to the Cable Act—in the context of broader efforts to strip Nisei of their citizenship. One only wishes for more on the actual lived experiences of Nisei in Japan in this prewar period.

His middle two chapters look at Kibei back in the US during the wartime incarceration, with one of the chapters narrowly focused on Toyoko Yamasaki’s notorious 1983 novel Futatsu no sokoku and its Japanese television adaptation, Sanga Moyu, which features a Kibei protagonist. The more general chapter argues that Kibei have served as bogeymen of sorts for both US government investigators and camp administrators and for segments of the Japanese American community itself, noting, for instance, that even “sympathetic” investigations of the Japanese American community by Kenneth Ringle and Curtis Munson singled out the Kibei as potential problems.

But the general treatment of the role of Kibei in the concentration camps presented here is a bit superficial. Jin argues, for instance, that Kibei played large roles in the unrest in the WRA camps over registration in early 1943, but cites only a single report from one camp, Topaz. The registration story varies greatly from camp to camp, with the role of Kibei varying as well. At Heart Mountain, for instance, resistance to registration came from a Nisei-led group (the Congress of American Citizens) that called on Nisei to reject registration until their citizenship rights were fully restored. Kibei groups did lead resistance at other camps such as Jerome. Again, a sense of Kibei life in the camps is missing; Jin tells us more about how others saw them, rather than how they saw themselves.

The last two chapters deal with the war years, one focusing on the dilemma of Nisei caught in Japan during the war, the other on Nisei hibakusha. Though certainly informative and insightful, both feel a bit cursory. The former uses the story of Tamotsu Murayama, a 1930s Japanese American Citizens League leader who morphs into a vocal cheerleader for Japanese imperial expansion by 1942, to discuss the pressure of Nisei stuck in Japan to be “loyal” Japanese, even comparing views of people like Murayama to those of Mike Masaoka’s, if on the opposite side. But there is only brief treatment of Nisei dual citizens conscripted into the Japanese armed forces against their will and almost nothing on women’s experiences other than a brief mention of Iva Toguri. Curiously, there is no mention whatsoever of the most notorious of the Nisei caught in Japan, Tomoya Kawakita. The chapter on hibakusha focuses less on their wartime experiences than on their postwar difficulties in getting medical treatment as a population truly caught in between two countries. Jin calls them “essentially stateless in the postwar state regime of care and compensatory justice.”

In contrast, Buxton’s entire focus is on the experience of Nisei caught in Japan during and after the war, though her first two chapters provide background on the Nisei experience in the US and in Japan before getting to the wartime story. Those chapters—which rely largely on secondary sources and on oral histories, including many from Densho’s archive—do a good job of setting the scene though they perhaps undersell the initiative of older Nisei leaders themselves in embracing Japan as a response to racism (as opposed to having that viewpoint foisted on them by parents and others). The second chapter introduces the idea of Nisei “code switching”—which Buxton defines as “exercises of cultural performance rather than innate, authentic aspects of an individual self,” and as the tool that enables Nisei to survive in wartime Japan and quickly transition to postwar life.

Her wartime chapters look at the experiences of the Nisei trapped there in the context of broader changes in Japanese society and pressures on all Japanese subjects to embrace sacrifice for the sake of the war effort. In so doing, she fills in many of the gaps left by Jin’s account, including detailed accounts of the roughly three thousand Nisei men who served in the Japanese military during World War II as well as a more nuanced story of Nisei women’s experiences. She points out how Nisei were treated differently than other foreigners—many of whom were segregated, interned or jailed—due to their Japanese ancestry which allowed them to be viewed as imperial subjects. But along with that special status came special pressures on the Nisei due to their suspect American-ness. Many also leveraged their English language skills—as was the case with Iva Toguri—as a means of survival.

The last two chapters look at the sudden transformation that took place at war’s end as Allied occupiers took over Japan, turning expectations upside down. Nisei who had hidden their American-ness during the war were now encouraged to embrace it, which some 5,000 did in taking jobs with the occupation. As in the war years, Nisei again had a sort of in-between status as “foreign nationals” that gave them access to higher salaries and food and medicine unavailable to native Japanese, but not as many privileges as Allied nationals. She also looks at the unique case of the Nisei renunciants and others who had lost their citizenship, whom she argues still enjoyed some benefits relative to native Japanese due to their connections to other Nisei and utility to the occupation due to their English language ability.

But in addition to bringing attention to this neglected story, Buxton’s broader mission is to reframe our understanding of Nisei “loyalty” in this period, and though she doesn’t say this explicitly, perhaps to remove the stigma of “disloyalty” that has clung to this population even if it is finally starting to fade. In doing so, she argues for a rethinking of what “collaboration” means in this context. She argues that those focused on “loyalty” as an explanation for Nisei behaviors are missing the boat and that “loyalty” is best understood as “the frame we use to rationalize an individual’s behavior in a moment of decision” and that actual behavior is influenced by a host of factors—”the physical environment, by discourse, by disciplinary forces, and by economic and interpersonal circumstances”—of which “loyalty” is just one element. She argues that we should rethink collaboration as a performance and that “By paralleling the process of collaboration of American Nisei in wartime and occupied Japan, it becomes clear that collaboration is a performance embedded in its historical moment.” Though I have split loyalties myself about this issue given my own family history, I find this viewpoint to be a refreshing and much needed rethinking of the Japan Nisei experience.

To be sure, both books have their issues. In Jin’s case the flaws are largely a result of the book’s ambition and scope, and provide openings for future researchers to add to the story. Buxton’s book might be a bit too jargon-y for the general reader, and repetitive in places. But overall, both are important works that significantly broaden our understanding of the Nisei story. We are indebted to Jin and Buxton for helping to bring our not so little club of “atypical” families into the mainstream of Japanese American history.

Michael R. Jin

Citizens, Immigrants, and the Stateless: A Japanese American Diaspora in the Pacific

Stanford University Press, 2022

A. Carly Buxton

Unthinking Collaboration: American Nisei in Transwar Japan

University of Hawaii Press, 2022

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

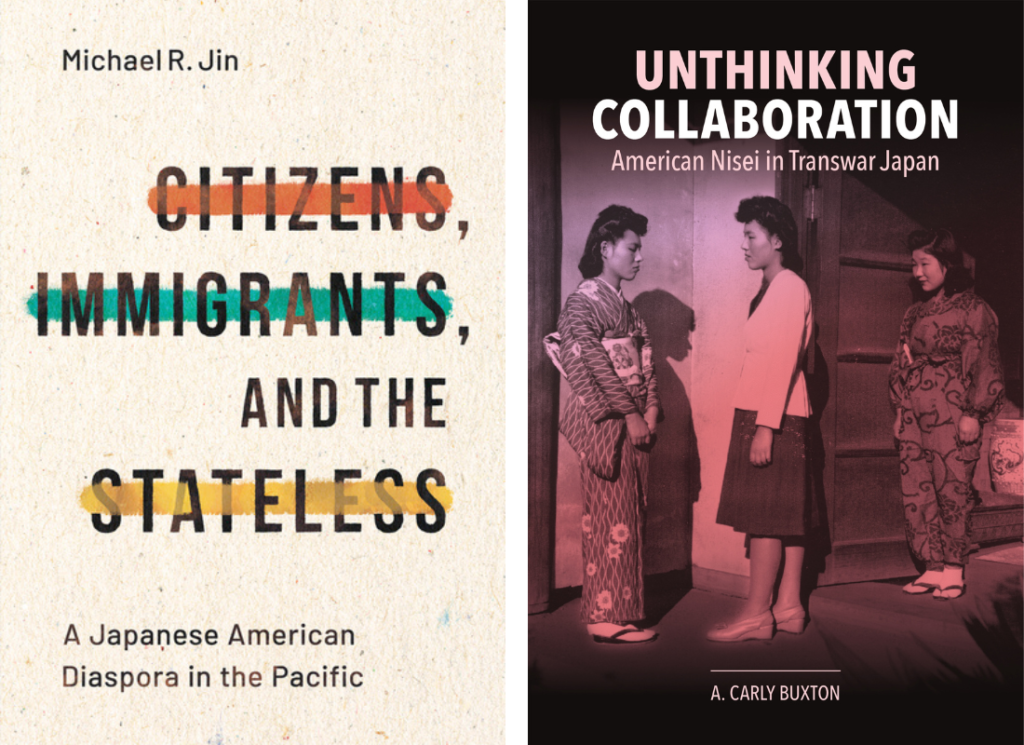

[Header: Nisei girl visiting family in Japan. Original caption: “Michi [Yasui]’s visit to Japan in the summer of 1940 Front, [left to right]: Yasuo, Michi, Kameno, Taiitsuro. Back, [left to right]: Tokiko, Norie (Yasuo’s wife), Hiroshi, Sachiko.” Courtesy of the Yasui Family Collection.]