June 14, 2018

I was reminded of this during a recent visit to the Manzanar National Historic Site. One of their newest exhibits in their recreation of a typical block is of toilets. No doubt in acknowledgement of centrality of toilets in camp narratives, they have built a replica of a women’s bathroom. In a small room are ten toilets with wooden seats, two rows of five, arranged back-to-back. There are no stalls or partitions of any kind. In addition to the lack of partitions, one is struck by how close the toilets are to each other, no doubt to minimize the cost of plumbing.

For the Sites of Shame update I’ve been working on in recent months, I’ve come across many accounts of toilets/latrines in the various confinement camps, both more or less contemporaneous accounts from diaries, journals, and letters and retrospective accounts in oral histories and memoirs. And bad as the scene at Manzanar and other War Relocation Authority (WRA) sites might have been, it is clear that things were worse elsewhere, particularly in the “assembly centers” run by the army that was the first concentration camp for most of the evicted Japanese Americans. So what follows is probably more than you ever wanted to know about this topic!

Squat Talk

While the toilets in the WRA camps lacked privacy, they were at least flush toilets for the most part. In many of the so-called “assembly centers,” the temporary camps run by the army, it was much worse.

Most of the assembly centers used existing facilities that were quickly adapted for use as short term detention camps—fairgrounds, Civilian Conservation Corps camps, horse racing tracks, and so forth. In many of the smaller rural assembly centers in Central California, the toilets were either of the pit variety or utilized primitive automated flushing systems. At the Marysville/Arboga camp, the “latrines were nothing but eight or ten foot pits and ¾ or ½ inch third grade pine with knot holes and knots dividing the men and women’s latrines. We were just back to back. God, that was awful,” Willie Ohara told Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) researcher Tamotsu Shibutani. He continued:

After the first few days all the latrines began to smell. After about four weeks they were practically overflowing. The administration began digging new latrines ten feet away from the existing latrines. They were so crudely constructed and so strategically placed that with every shift of wind the stench could be smelled at all times. I think those were the most disgusting things in the center.

Writer Hiroshi Kashiwagi, also at Marysville, described the latrine similarly in his memoir as “eight holes in a line without partitions between them.” Inmates at Sacramento and Salinas described the toilets there in similar fashion.

Perhaps one step up were the camps that had inmates sit above metal troughs that “flushed” automatically when water flowed at set intervals. Inmates at Merced, Tulare, Fresno, and Pinedale describe such systems. In her memoir that includes detailed descriptions of life at Pinedale, Mary Matsuda Gruenewald has perhaps the most vivid description of such toilets. As inmates sat over holes on raised platforms,

A faucet at one end of the row of toilets dripped water constantly into a trough. The water ran below and slightly behind the toilet holes. I quickly learned to recognize when the sound of the dripping water got to a certain pitch; this meant enough water had accumulated to make the trough tip. That would force enough water to ‘flush’ the contents down to the other end and into the sewer below. The first time I had to go to the bathroom I didn’t know this. I got an unwelcome splash of cold water all over my bottom. Never again.

Once baptized in such an unsavory fashion, inmates knew to watch for the “flush.” As Gruenewald continues, “… everyone inside paid close attention to the sound of the dripping water while they sat on the toilets. When it reached that certain pitch, everyone silently raised their rear ends in unison while the contents were flushed away. Solemnly everyone resumed their previous positions.” Finding humor in retrospect, she concludes that the “moment made me chuckle in spite of the circumstances.”

In addition to the general issues of smell and privacy, these trough systems were flawed in other ways. In his field reports from Tulare, JERS fieldworker James Sakoda found that many inmates complained that the seats were too high for children and that the “flushing” system “is not entirely satisfactory as it washes down only the center of the trough and does not catch all of the material that accumulates higher up on the edge.” As Gene Oishi wrote in his memoir In Search of Hiroshi, “Most of the time, though, the water pressure was not strong enough, so the latrines were usually filthy, smelled, and swarmed with flies.” Echoing the sentiments of other former inmates, he added, “Even today, when under stress, I dream of filthy toilets filled and covered with human feces.”

The larger (and more urban) assembly centers—Santa Anita, Tanforan, and Manzanar—had some version of flush toilets. But at Santa Anita, at least, the flush toilets were connected to cesspools that were prone to overflowing. “And can you imagine Santa Anita parking lot when the cesspool starts to overflow?” asked Osamu Mori in an interview in the Densho Digital Repository:

“I mean, gee, terrible. I don’t know what… I guess the cesspool system is supposed to go into the ground, seep into the ground. But there’s just too much activity. It used to overflow anyway.”

The move from the primitive army run “assembly centers” to longer term WRA run concentration camps generally meant a move to flush toilets. For many inmates, this was a welcome development. For some, this was a first, since they had come from farms where outhouses were used. As Hank Umemoto remarked in a Densho interview, “to me it was good because I came from a farm. We had outhouses, right? At camp they had high tech flushing toilet.” In her memoir, Mary Tsukamoto wrote that she was “pleased with the gleaming white, porcelain, flush toilets,” while Hiroshi Kashiwagi wrote that upon arriving at Tule Lake, he and his friends “made a special trip to the latrine to check them out—two rows of porcelain toilets that actually flushed.” They excitedly “tried it several times to see if they really worked; they did.”

But in the same breath, Tsukamoto and Kashiwagi added a big “but.” The former wrote, “The only thing we didn’t like was the long, open wall of toilets with no partitions”; the latter, “However, the lack of partitions between the toilets and the trough urinals for the men were a bit disconcerting.”

This lack of privacy was a core issue for many. “I stand by the corner of our barrack trying to appear nonchalant, but in truth, I am miserable,” wrote Kiyo Sato in her memoir. “How can I sit in the latrine between all those people, or have my back against a stranger? What am I going to do?”

“For the first time in my life, I was forced to relieve myself on the toilet in the presence of total strangers,” wrote Minoru Kiyota in his memoir. “Or rather, to make the attempt. I don’t believe anyone, no matter how thick-skinned, would find it easy to use a toilet that is just one long plank of plywood with holes in it—with no semblance of privacy and with maggots swimming the tank below. Adjusting to this novel way of going to the bathroom was our initiation rite into communal living, a rite that took most of us a good long time to pass.”

Yet another issue with the latrines was distance. With central latrines serving hundreds of inmates, distances to the toilet could be long, particularly in cold weather or snowy conditions. In the assembly centers, searchlights also beckoned; there are many inmate accounts of nighttime bathroom visits being turned into frightening affairs when guard tower searchlights would follow individuals to and from the facilities. And as my colleague Nina Wallace recently noted, camp latrines were also notorious sites of harassment and violence.

Making Do

As was the case with many aspects of concentration camp life, Japanese Americans found ways to adapt to the situation. In some of the assembly centers, there were areas that had flush toilets, and inmates maneuvered to get access to them. At Arboga, Kashiwagi volunteers to work at the hospital in part because he could then use the flush toilets there. At Tanforan, Ben Iijima discovers that the existing latrines that had been made for patrons of the race track were “constructed more durably than the barrack type.” He also finds that “There are partitions separating the bowls and that is the main reason why I go to this latrine.”

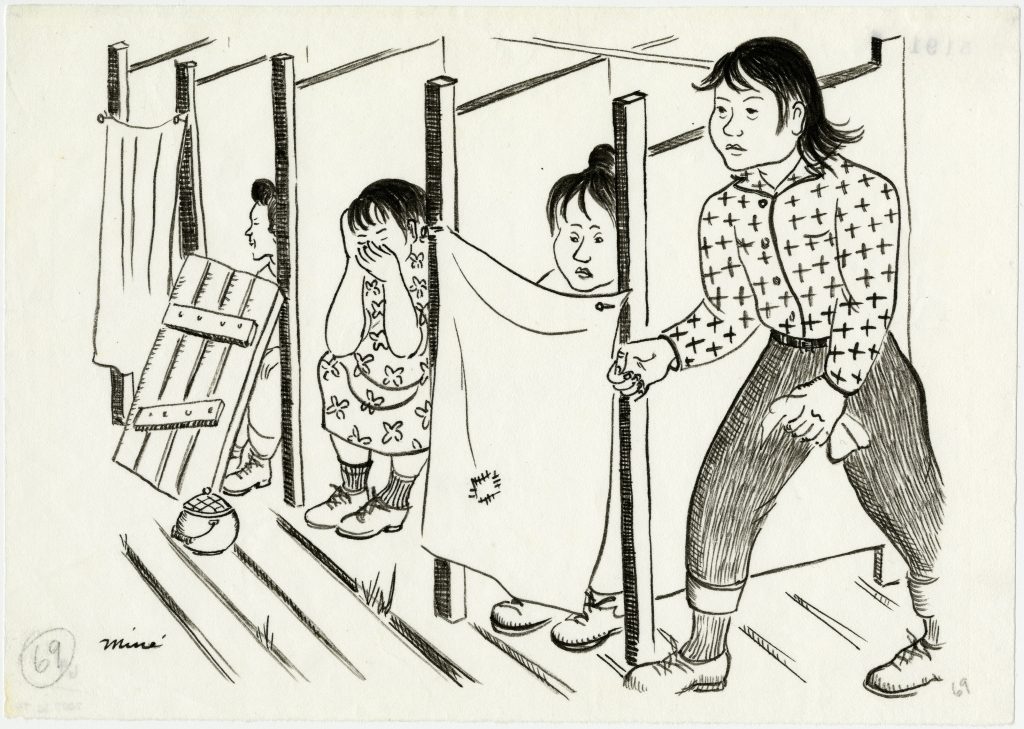

To deal with the privacy issues, there are many accounts of inmates trying to go to the bathrooms at odd hours of the night to avoid crowds or improvising partitions made of cardboard boxes or other materials. Sue Embrey recalls that inmates “brought coats and other things and took turns covering the stalls so they had some privacy.” In some cases, inmates themselves constructed at least some partitions; in other cases, camp administration added partitions over time.

To avoid late night bathroom trips in cold weather, many inmates used chamber pots. (Should we add “chamber pots” to the list of camp euphemisms?) Though convenient especially for older people, they also required cleaning out in the mornings. In his diary, JERS fieldworker Charles Kikuchi hears of inmates who used milk bottles in lieu of chamber pots. “Since there are no individual toilets in these stables, various systems have been devised,” he succinctly observed.

The chamber pots led to high comedy in at least one case.

As Yukiko Miyake related in a Densho interview, one Issei woman used to make otsukemono (pickled vegetables) in the chamber pot:

“And when I was sick, this lady was kind enough to make some otsukemono for me and bring it over, [Laughs] and my friends wouldn’t let me eat it because they said, ‘How can you? How do you know she didn’t make a boo — you know, make a mistake?’ So I never ate her otsukemono, but I always had to tell her how nice it was and thank you very much. I never knew who the lady was, but she was always bringing otsukemono over, but my friends said, ‘No don’t touch it. Don’t touch it.'”

But perhaps the ultimate adaptation was a philosophical one to a core condition that one could do little about. Kashiwagi, who would go on to become a well-known poet and playwright wrote that an “oft-heard remark in the latrine was ‘Erai toko de deaimasu, neh!’ which might be translated as ‘What a place to be meeting’ or ‘What an ungodly place to meet’ or ‘What a miserable situation we find ourselves in.'” In a similar vein, James Sakoda wrote in his diary that he was “sitting in the toilet when a man came and sat down too. The man said that at first he felt rather awkward coming in. Now, he says, he feels a congeniality, sitting and talking together. ‘You have to get used to things,’ he said.”

As evidenced by all of these accounts of bathrooms and toilets—and there are many, many more—as well as the display at Manzanar, people are interested in this topic. I hope this short account also shows how this topic is a microcosm of the incarceration experience as a whole: broadly similar experiences with many specific variations; adaptations by inmates to the conditions they faced; and gradual change over time. But I think in the end the appeal of this topic is that it is something that we can all identify with—as the title of the children’s book series bluntly puts it, Everybody Poops—and it is something we can point to as a small but vivid symbol of the dehumanization that the mass incarceration represented.

—

By Densho Content Director Brian Niiya

Header image: Latrines at the Tanforan detention facility, June 1942. Photo by Dorothea Lange, Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.

Sources

The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive

These sources come from the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS), a UC Berkeley based research project that took place as the incarceration was ongoing. Material here is listed by JERS folder number with an online link.

Willie Ohara, second interview with Tamotsu Shibutani, Oct, 25, 1943, folder T1.9931, p. 5.

James Sakoda diary, May 22, 1942, folder B12.20 (1/2), p. 68.

Ben Iijima diary, July 13, 1942, folder B12.10 (3/4), p. 117.

Charles Kikuchi diary, July 10, 1942, folder W 1.80:02**, p. 344.

James Sakoda diary, May 27, 1942, folder B12.20 (2/2), p. 17.

Densho

Osamu Mori, interview by Richard Potashin, Segment 8, Concord, CA, Apr. 14, 2010, Manzanar National Historic Site Collection, Densho Digital Archive.

Hank Shozo Umemoto interview by Tom Ikeda, Segment 17, Los Angeles, CA, July 30, 2010, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Archive.

Yukiko Miyake interview by Sara Yamasaki, Segment 29, Seattle, June 4, 1998, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Archive.

Memoirs

Hiroshi Kashiwagi, Swimming in the American: A Memoir and Selected Writings (San Mateo, Calif.: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2005), pp. 83, 86

Mary Matsuda Gruenewald, Looking Like the Enemy: My Story of Imprisonment in Japanese-American Internment Camps (Troutdale, Ore.: NewSage Press, 2005), p. 54

Gene Oishi, In Search of Hiroshi: A Japanese-American Odyssey (Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1988), p. 48.

Mary Tsukamoto, and Elizabeth Pinkerton, We the People: A Story of Internment in America (San Jose: Laguna Publishers, 1987), p. 130.

Kiyo Sato, Kiyo’s Story: A Japanese-American Family’s Quest for the American Dream (New York: Soho Press, 2007), p. 153.

Minoru Kiyota, Beyond Loyalty: The Story of a Kibei, Translated from Japanese by Linda Klepinger Keenan (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1997), p. 68.

Diana Meyers Bahr, The Unquiet Nisei: An Oral History of the Life of Sue Kunitomi Embrey (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), p. 53.