October 12, 2018

Before the war, Japanese immigrants to the United States were known to be successful farmers. Though racist land laws prevented them from owning property, many were able to purchase land by putting deeds in the names of their citizen children.

After FDR signed Executive Order 9066, many were forced to sell or lease their land far below market value. Some scholars argue that seizing this lucrative property was a major motivation behind Japanese American incarceration.

For example, Yoshimi Matsuura’s family had to sell their vineyards for a total of $23 per acre, instead of the $200 per acre they would have netted if they had been allowed to stay and harvest the grapes themselves.

In 1942, the managing secretary of the Western Growers Protective Association “reported that considerable profits were realized by the growers and the shippers because of the Japanese removal.”

Some had friends and neighbors who cared for their property, like Bob Fletcher who quit his job in order to maintain Japanese American farms and accounts, then handed a large portion of the profits back to the families after the war.

Others entrusted their land to people who took advantage of their misfortune. Harvey Watanabe recalled coming home to find stolen and vandalized property on his family’s farm:

“The farm was leased,” he told Densho, “but the lessee just stole everything.”

In the War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps, incarcerees had to grow their own food if they wanted to have fresh vegetables. People of all ages were made to work long hours in the field or in processing centers.

The work was rigorous and inmates were not provided with adequate equipment to meet the demand. Their diets were insufficient for the physical demands they were expected to meet. Worker strikes and stoppages erupted across the camps.

At Heart Mountain, farm workers went on strike after camp administrators refused their requests for better farm equipment. According to Karl Lillquist, “administrators responded by bringing in ‘strike breakers’ from the center’s high school.”

“Tule Lake had to bring in evacuees from other centers to complete the 1943 harvest during a major strike.” Causing further tensions, strike breakers were paid prevailing ‘outside’ wages of $1.00 to $1.45 per hour rather than concentration camp wages of $12 to $16 per month for manual labor.

Some incarcerated Japanese Americans were able to get temporary farm work releases. Uprooted Exhibit estimates that between 1942 and 1944, some 33,000 individual contracts were issued for seasonal farm labor, with many working in the sugar beet industry.

Densho Content Director Brian Niiya notes:

“Japanese Americans removed from their own farms were now being practically begged—with blatant appeals to patriotism—to do farm labor on other people’s farms to ‘save’ crops from a labor shortage due in part to their incarceration.”

And while work releases came with the benefit of getting out of camp and earning higher wages, laborers who participated faced challenges ranging from wage theft to blatant discrimination at area businesses. In some camps, the numbers of inmates who left to do agricultural work created major labor shortages in the camps to the detriment of the inmates who stayed behind.

At the end of the war, land at Tule Lake, Heart Mountain, and other camps was sold to homesteaders. Forced Japanese American farm labor had helped transition stolen Native American lands into lucrative farmlands for white settlers.

So, yes, we should celebrate the hard work of farmers today but we can’t do so without acknowledging the role of farming in some of our country’s ugliest histories — from appropriation of Native lands and slavery to ongoing exploitation of immigrants and incarcerees.

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications and Public Engagement Director

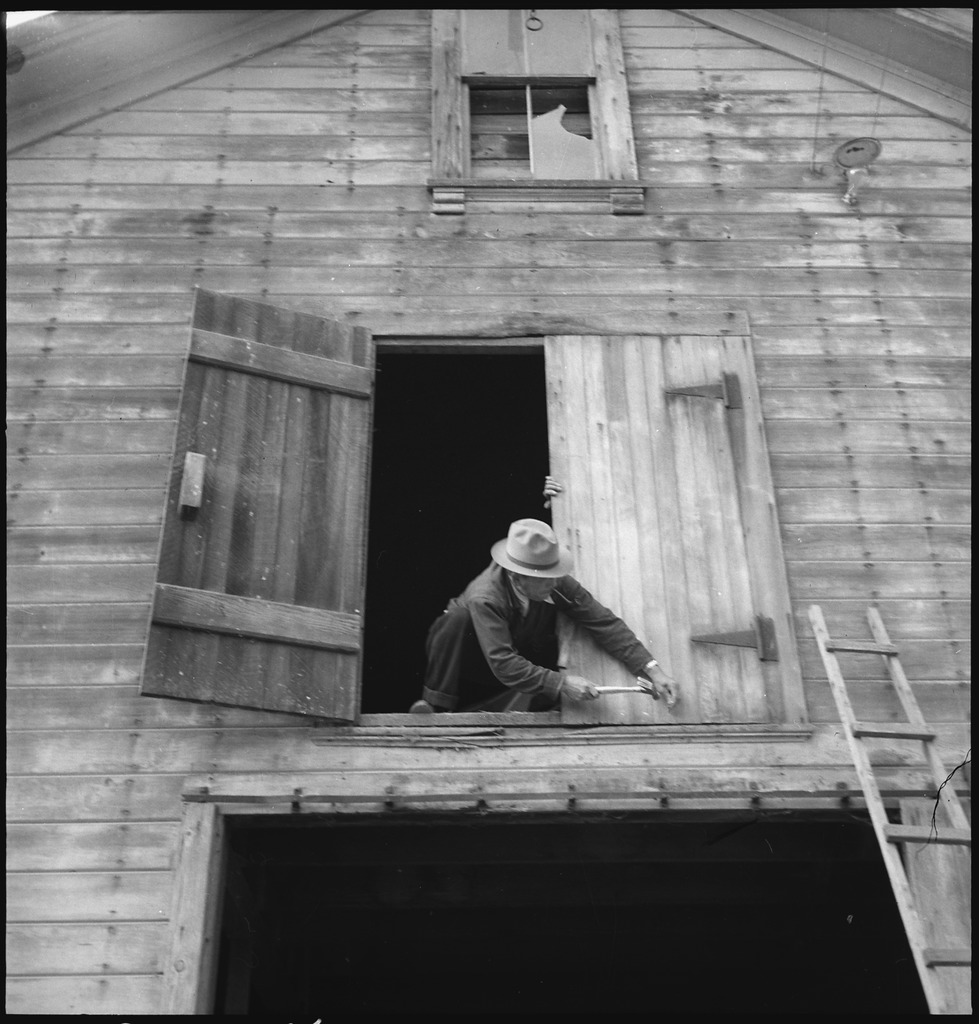

Header photo: In Centerville, California, a man nails shut the hayloft door on the morning of evacuation. May 9, 1942. Photo by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.