March 28, 2024

In late 1943, three Japanese American sisters helped two German prisoners of war escape from a southern Colorado POW camp. The men were soon caught and sensationalized stories of “Japanazi romance” and treason, along with a photo of one prisoner locked in an amorous embrace with one of the women, captivated media attention across the country. But as scandalous as the story was then, today the Shitara sisters have been relegated to a minor footnote — perhaps in part because they complicate familiar narratives around Japanese American patriotism, loyalty, and innocence in the face of WWII incarceration.

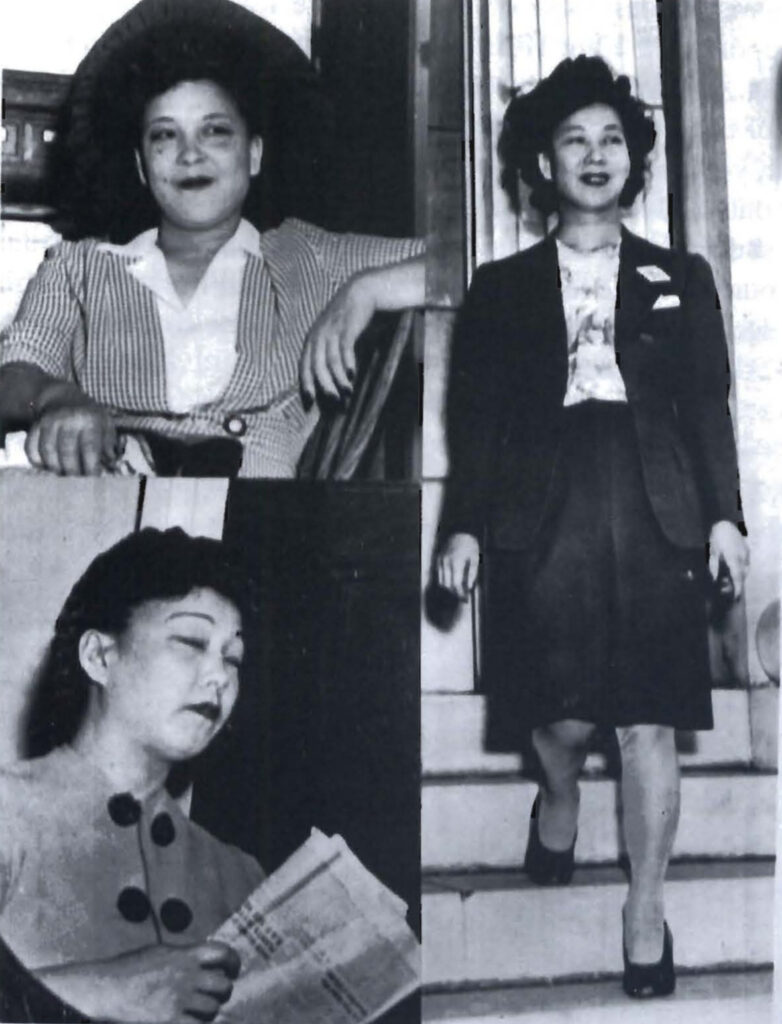

The Nisei sisters, Tsuroko “Toots” Wallace, Shizue “Flo” Otani, and Misao “Billie” Tanigoshi — née Shitara — had grown up on a farm in Inglewood, California where they were largely isolated from other Japanese Americans. The two older sisters, Toots and Flo, were living on Terminal Island with their husbands when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor drew the US into World War II. They were given just 48 hours to pack up and move inland when the small cannery town became the first Japanese American community targeted for forced removal on February 25, 1942. All three sisters were imprisoned with the rest of the Shitara family first at the Santa Anita Assembly Center and later at the Amache concentration camp in southeastern Colorado.

In the spring of 1943, Toots, Flo, and Billie received leave to work on an onion farm close to the New Mexico border. Also working on that farm were German prisoners of war brought in from nearby Camp Trinidad, a POW camp that held more than 3,000 captured German soldiers.

Though the exact chain of events that followed remains a little murky — and changed several times during the subsequent investigation — what is known is that the Shitara sisters met Heinrich Haider and Hermann Loescher while working on the onion farm. The two prisoners, eager to escape, approached the sisters and asked for their help in procuring civilian clothes. They eventually agreed — after a good deal of persuasion, according to a letter Loescher would later write to the judge presiding over their case — and offered to pick up the men on a highway at the edge of the POW camp.

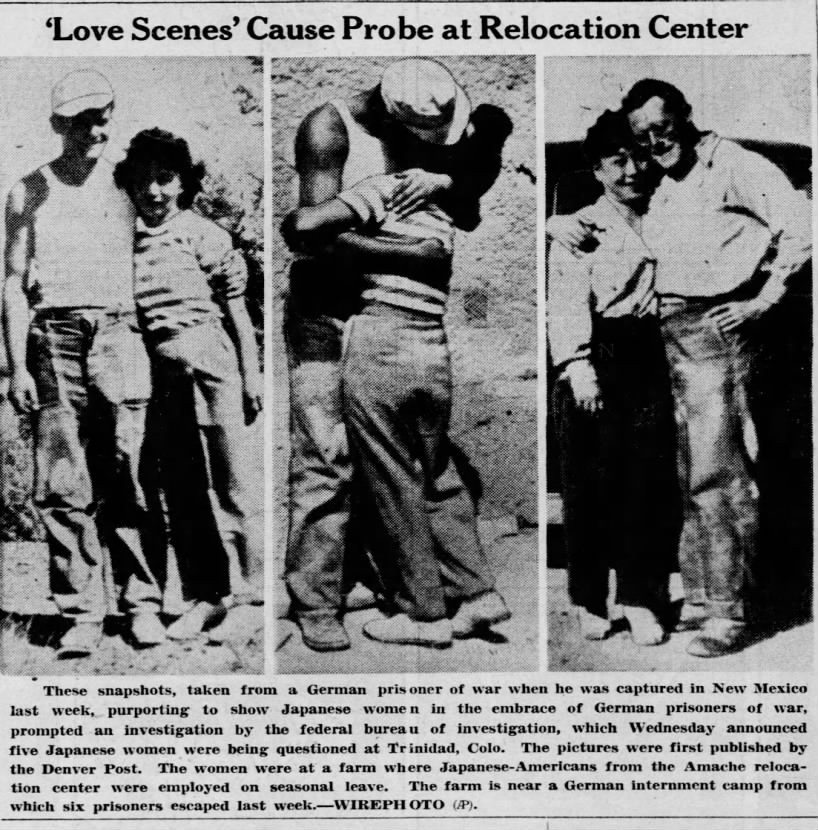

Under cover of darkness on the night of October 17, 1943, Haider and Loescher made their escape and found their way to the Shitara sisters’ waiting car. They drove the men south, reportedly with Toots at the wheel, until they developed engine trouble and had to turn around, leaving the men to continue across the desert on foot with some road maps, a little cash, and three photos of Billie and Toots with the two POWs. The men made it as far as the tiny town of Watrous, New Mexico, about 90 miles south of Camp Trinidad, but drew attention after trying to buy train tickets. They were arrested carousing in a bar with some local women barely two days after their escape.

Haider and Loescher initially claimed they had escaped on their own. But the souvenir photos — including one that showed Haider and Billie entangled in a kiss — contradicted their story and authorities quickly tracked down the Shitara sisters for questioning. The photos landed on the front page of The Denver Post a few days later, with the headline “German Prisoners Spooned with Jap Girls in Trinidad,” and was soon picked up by newspapers across the country.

Coverage in the Japanese American press, while not steeped in the racial and sexual stereotypes of the mainstream media, was also critical of the Shitara sisters. “I’ve seen and heard many a man go crazy over some stupid woman, but this beats all,” scoffed a letter printed in the Granada Pioneer. “While our buddies are fighting and dying in Italy against the Germans and to find some of our girls at home are making love to German war prisoners. That is enough to make any good man go batty.”

Over the next several months, the FBI, Justice Department, and War Relocation Authority investigated the case, going back and forth over whether the sisters’ indiscretions amounted to treason. Under the laws of the time, a charge of treason — a capital offense which carried a possible death sentence — required proof of intent to harm the United States and aid their enemies. But the evidence against the Shitara sisters, while proving they had made some questionable choices and not exactly behaved as modest young ladies, did not point to any political motive. In fact, it seems the main source of the government’s claims of treasonous intent was a comment from Loescher during his interrogation, speculating that the women “feel allegiance to Japan and to its ally Germany” because they had “not been accepted by Americans” due to their Japanese ancestry.

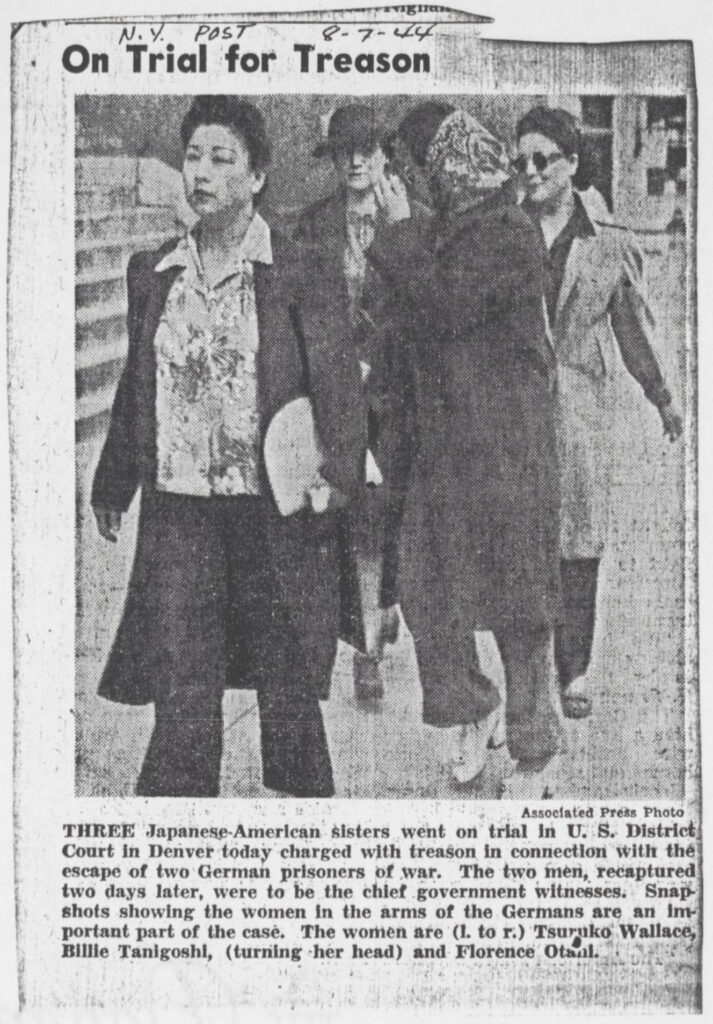

Nevertheless, the Attorney General authorized the prosecution of the sisters in March 1944, and on May 9, Toots, Flo, and Billie were indicted by a federal grand jury for treason and conspiracy to commit treason.

The trial — dubbed the “most dramatic trial that ever has been held in Denver” by the Rocky Mountain News — began on August 7 and lasted just a few days. Both Haider and Loescher gave testimony that clearly implicated the sisters in aiding their escape, but they also said nothing to support the prosecution’s claims that the women held any allegiance to Germany or Japan. All three Shitara sisters declined to testify, much to the disappointment of nearly 300 spectators “perspiring and fanning themselves in the sultry room, sat on the edge of their seats.”

In his closing arguments, the Shitara sisters’ court-appointed attorney urged the jury to see that the women were guilty not of treason but of having “foolish” and “frail” hearts too easily led astray. But, countered the prosecution, it was precisely this love — for men other than their husbands — that proved the sisters’ guilt: “These are traitors — little Benedict Arnolds in skirts,” argued US Attorney Thomas Morrissey. “They were not true to their husbands, nor, gentlemen of the jury, were they true to the United States of America.”

After eight hours of deliberation, the all-male jury found Toots, Flo, and Billie guilty of conspiracy to commit treason but not treason itself — a rather confounding verdict considering the proof of intent required to support a charge of treason was the same as the proof needed for the conspiracy charge. This point was not lost on the sisters, one of whom was heard to mutter, “How can it be conspiracy to commit treason if we’re not guilty of treason?”

Despite this apparent legal contradiction, the judge praised the verdict as “a very fair one” — a sentiment echoed in mainstream news coverage, which heralded it as a just “compromise.” Even the editors of the Pacific Citizen, the national paper of the JACL, seemed to agree, chastising the sisters even as they acknowledged the racist presumptions of collective guilt at the heart of the case: “The trial has been a dramatic reminder of the effects of such reckless disregard of the group responsibility which must be borne by all Americans of Japanese ancestry, so long as Japanese Americans continue to be treated as a racial unit.”

The Shitara sisters were sentenced and served their time at a federal women’s prison in West Virginia, with Toots, who was seen as the leader of the three, receiving a slightly longer term than her two younger sisters. Given their lack of testimony during the trial — and the quiet, out-of-the-spotlight lives they led after returning to their families in California in 1946 — there is little of their own voices and perspectives in the historical record. But we can catch glimpses here and there: In Toots’ request to serve out a “double sentence” so that Billie might go free to care for their two young daughters. In responding to the verdict with audible disappointment rather than being “limp and quiet and grateful,” as one particularly vicious news article argued they should have been.

On the surface, the Shitara sisters occupy an uneasy, even dangerous place within the larger narrative surrounding Japanese American WWII incarceration. Their conviction — along with similar, though less salacious, treason charges later brought against Iva Toguri D’Aguino and Tomoya Kawakita — seems to contradict the oft-quoted line that no Japanese Americans were ever found guilty of sabotage against the United States. That the incarceration was wrong not because of its roots in entrenched and interwoven systems of state violence, but because of Japanese Americans’ pristine innocence and unimpeachable loyalty. And it is perhaps because of that contradiction that their story has largely been left alone and untouched in the past. But, as Eric Muller argues in his detailed account of the trial, “the experience of the Shitara sisters should play a prominent and unashamed role in illustrating the civil rights tragedy we call the Japanese American incarceration.”

Toots Wallace, Flo Otani, and Billie Tanigoshi were not beacons of morality or feminist icons. But neither were they the proof of Japanese Americans’ potential for disloyalty, and of women’s inherent frailty and need for patriarchal influence, that they were painted to be. The Shitara sisters were punished in large part for being Japanese American women who pursued romantic relationships outside their marriage and their own race. That kind of disloyalty — against the same stereotypes and racialized assumptions that fueled the forced removal and incarceration of the Shitara sisters and 125,000 other Japanese Americans — is something we can all stand to learn from.

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Media & Outreach Manager

This work is based on Eric Muller’s Densho Encyclopedia article on the prosecution of the Shitara sisters, “Betrayal on Trial: Japanese-American ‘Treason’ in World War II” (also by Eric Muller), and a JERS compilation of contemporary news coverage of the Shitara trial. For further reading, see “‘Little Benedict Arnolds in Skirts’: Japanese American Women and Treason in World War II Colorado” by Robert Koehler (Heritage of the Great Plains 43: No. 2).

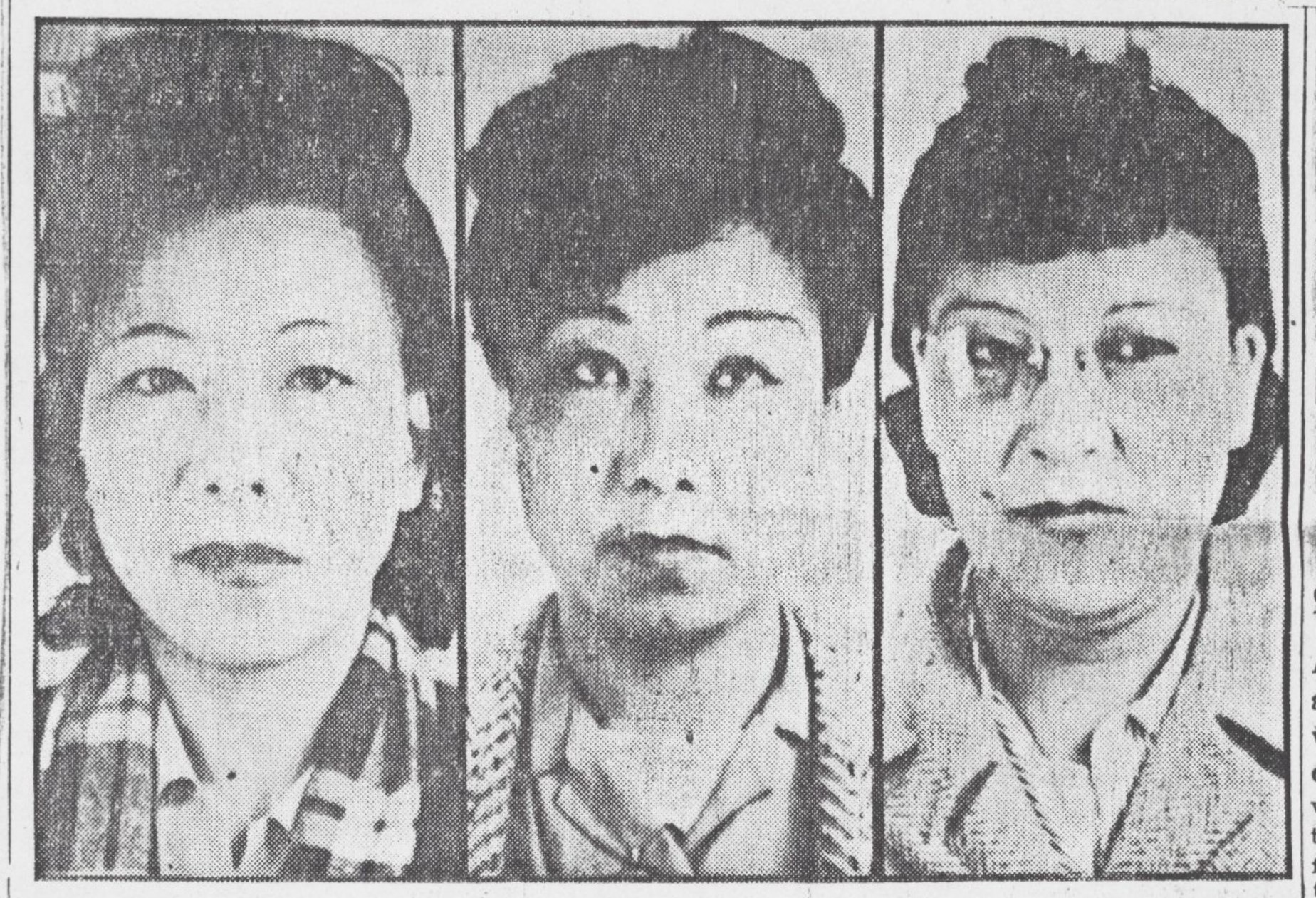

[Header: Mug shots of the Shitara sisters after their arrest, left to right: Billie, Toots, and Flo.]