July 19, 2019

The Japanese American Citizens League is considering a resolution that proponents say would help heal a decades-old wound. The conflict stems from the disastrous “loyalty questionnaire” administered by the US Government to Nikkei citizens and immigrants being held in WWII concentration camps. Based on their responses to two questions, some 12,000 incarcerees were further penalized by the US Government and ostracized by members of their community. The resolution contends that “this stigma of ‘disloyalty’ and being branded as ‘no-no’s’ persists to the present day,” and that a formal apology from the JACL would help the community heal.

As the JACL membership considers this resolution, we offer some historical context that we hope will lead to deeper understanding of this complex and sensitive topic.

So what was the so-called “Loyalty Questionnaire” anyway?

In 1943, the War Relocation Authority and the War Department joined forces to try and suss out Japanese American military recruits and loyal citizens that could be released early from concentration camps. The questionnaire required respondents to name references outside camp, list the publications they read, and share other relatively mundane details. The majority of the questions were patronizing and insulting given the circumstances, but largely benign.

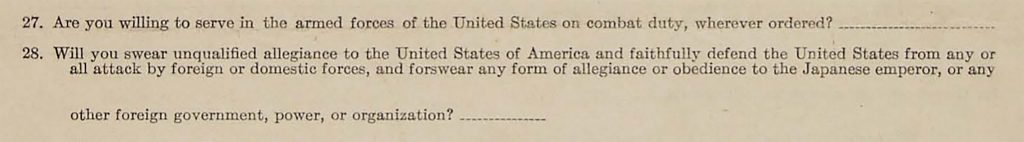

However, Questions 27 and 28 were particularly problematic:

Some respondents answered no to these questions because there was confusion and too little information about the consequences of answering “yes.” In a March 2019 interview with Densho, Ben Takeshita explained some of the confusion surrounding the two questions.

Of Question 27, Takeshita said:

“Now, if you were a young mother with kids, how could they, if they were responsible parents, how could they answer this ‘yes and serve on combat duty wherever ordered’? And also a father who had young kids yet, and was responsible for the family, how would he be willing to, or be able to answer this ‘on combat duty wherever ordered’?…So there was a lot of rumors about how to answer this question, and I remember rumors that this was one way that the United States was going to try to get rid of us by sending us all to combat duty. So there was a lot of questions as to how to answer that question.”

And of Question 28’s prompt to “forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor,” Takeshita noted:

“Many people who lived in the United States were born in the United States, had no idea who the Japanese emperor was. Of course, our parents knew because they were born in Japan and immigrated legally to the United States. But so if you answer this ‘yes,’ then that means that at one time you had sworn allegiance to the Japanese emperor, and now you’re swearing allegiance to the United States. And besides, our parents were Japanese citizens, born in Japan, they were forbidden by American alien land law in 1924 where they could not become American citizens even though they wanted to, and they could not own property. So it again became a dilemma, because like my parents, if they answered it ‘yes,’ then they would be a person without a country.”

In addition to the confusion surrounding the two questions, some opposed them on moral grounds, as Hiroshi Kashiwagi explained in his interview with Densho:

“Well, you know, the way we were treated, as non-citizens, and then to be, to asked, ‘Are you loyal?’….I mean, we certainly were loyal. Had we not been in camp, I mean, there was no question. And I remember the Nisei who were being drafted before the war, and I was in this men’s group, young men’s group, and we would have little parties, going-away parties for them. And I was picked to give a little speech. And so I would make this funny old patriotic speech, urging them to serve their country and so forth. And, yeah, so, but once we were treated like we were, then, yeah, I couldn’t register and say, ‘I will serve in the army wherever sent,’ and so forth. I really couldn’t.”

Tule Lake as Segregation Center

The people who answered “no,” refused to answer, or qualified their responses were branded “disloyal” and dubbed “no-nos.” The WRA moved to segregate them from the rest of the incarcerated population.

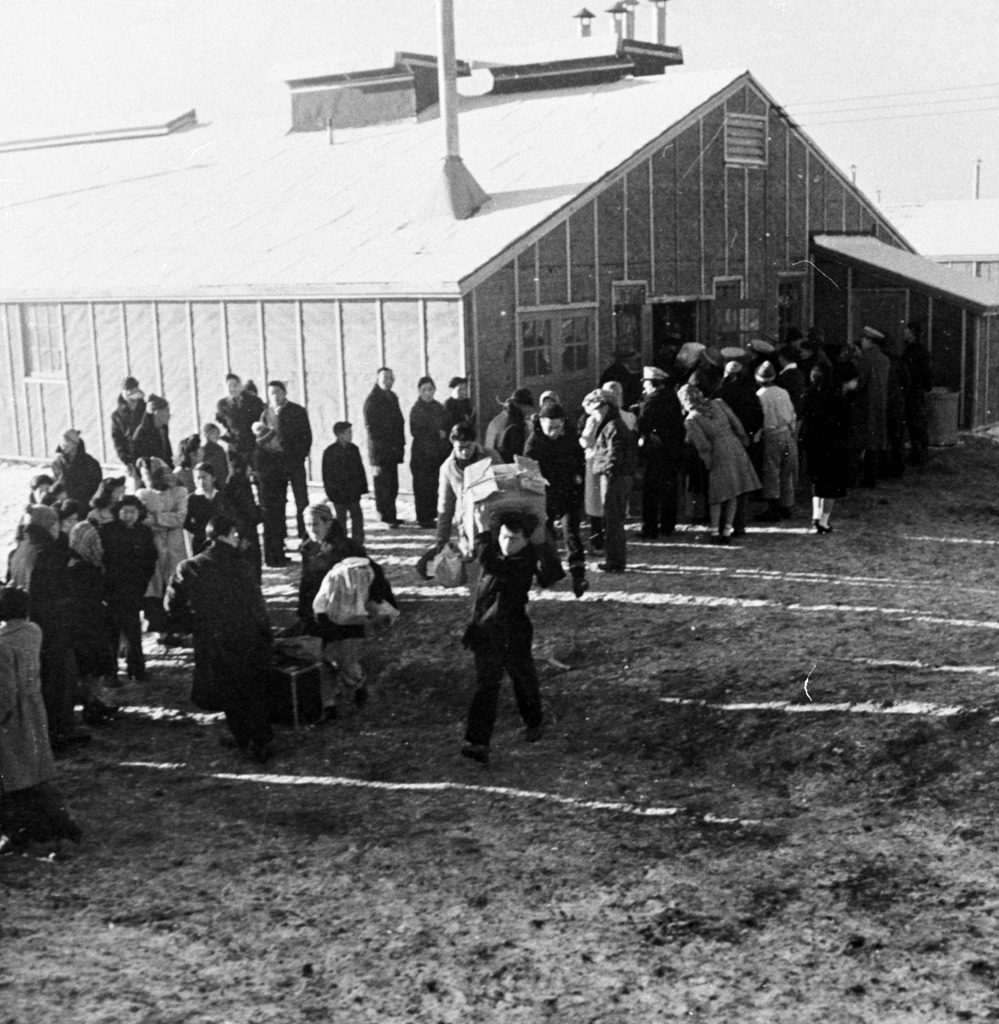

Because of Tule Lake’s capacity and its high number of incarcerees who had given the “wrong” answers to questions 27 and 28, that camp was designated as the site where “no-nos” from all 10 camps would be concentrated. Under pressure from Congress, the army, and the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), Tule Lake was officially rebranded a “segregation center” as of July 15, 1943. Twelve thousand segregees were moved to Tule Lake, while some 6,500 Japanese Americans who had supplied the desired responses were relocated to other WRA camps.

Barbara Takei writes in the Densho Encyclopedia that, “under segregation Tule Lake became a very complicated prison camp, bringing together the leaders, organizers and the disaffected from the other nine camps, making up two-thirds of the segregation center’s population. The remaining one-third of the population were the so-called ‘loyals’ who did not want to leave Tule Lake for removal to another WRA camp, a decision that contributed to much turmoil at the segregation center.”

Tule Lake incarcerees witnessed in increase in security, including more barbed wire and an additional fence being built around the camp’s perimeter; the arrival of 1,000 military police with armored tanks and cars; and an additional 22 guard towers built alongside the six that were already there. Inmates pushed back against deteriorating conditions, unsafe working conditions, and the increased security. The WRA responded with even harsher treatment, including the use of tear gas, curfews, barrack searches, and the imposition of Martial Law, which led to even greater suffering among the men, women, and children detained at Tule Lake. A separate “prison within a prison” was built to further punish those who resisted the US government’s unlawful treatment.

In addition to all the strife Tuleans endured because of the US government, they were also ostracized by other Japanese Americans. The stigma associated with Tule Lake and being branded “disloyal” created painful divisions among friends, families, and the community that linger to this day.

So what did the JACL have to do with this?

As part of its efforts to cooperate with the US government and prove that Japanese Americans were good citizens, the JACL condemned acts of dissidence during and after the war.

Deborah K. Lim’s 1990 investigation of the JACL’s wartime activities revealed that the JACL hoped to disband any “disloyal” members. She writes that “inter-office correspondence beginning May 19, 1943 from Saburo Kido to Teiko Ishida contains the following discussion:

“Regarding members who answered ‘no’, Mike [Masaoka] suggests that we send out a bulletin to all chapters that such members will be suspended. He believes this is necessary for our records; that is, we should be clear as to the loyalty of our members. Also we cannot accept anyone who has answered, ‘no.’”

Because the JACL had no way to know for certain who was a “no-no,” they created and administered their own Loyalty Oath. In order to renew membership in the organization, individuals had to supply notarized proof they had taken the oath.

Lim concludes, “What is both implied and expressed in this correspondence is the presumption that those who answered ‘no’ to both questions were disloyal, and should be dealt with accordingly.’

Cherstin M. Lyon writes that after the war, the organization doubled down on its decision to condemn “no-nos” and other resisters:

“In February 1946, the national board of the JACL met during the Ninth Biennial National Convention in Denver, Colorado, and discussed what position they would take regarding all those who had protested their wartime treatment, including those who had renounced their citizenship and requested repatriation to Japan, ‘No-No’ resisters, and draft resisters. In response, the board formally condemned all of them, contributing to decades of marginalization for Japanese Americans segregated at Tule Lake, Nisei draft resisters, and others labeled ‘disloyal’ for their wartime resistance.”

A lasting stigma

In her interview with Densho, Chizuko Norton recounted the negative response she received when people learned she had been incarcerated at Tule Lake:

Chizuko Norton: “And it was interesting to meet other Niseis, except that one of the first things that we would ask each other when we would meet a Nisei is, ‘Where were you in camp?’ And so if the word was Tule Lake, with all the, the horrible things that we had gone through—and people had associated that with us—that surely we must have been one of the ‘no-no’ people.”

Interviewer: “And so you received a negative reaction?”

CN: “Yes, of course. And not only by the returning veterans who really couldn’t stand us, but by most of the women students, too.”

The resolution currently under consideration by the JACL membership asks that, “in the spirit of reconciliation and community unity, a sincere apology is offered to all those imprisoned in the Tule Lake Segregation Center for acts of resistance and dissent, who suffered shame and stigma during and after the war due to the JACL’s attitudes and treatment towards individuals unfairly labeled ‘disloyal.’”

Given the importance of resistance then and now, Densho’s hope is that the stigma of disloyalty is lifted from those who courageously opposed the unjust actions of our country so that we can honor their actions and move towards healing.

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications and Public Engagement Director

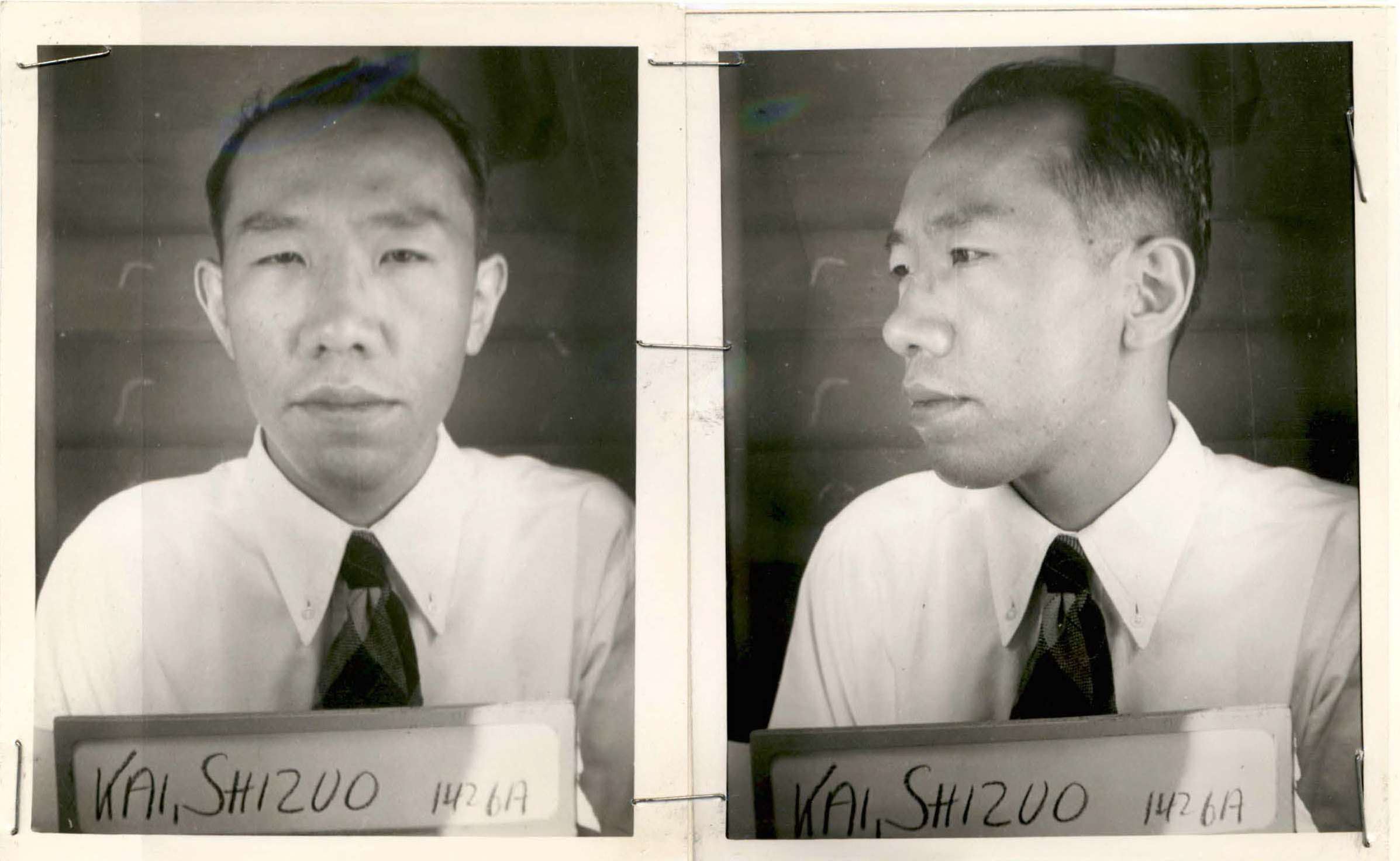

Header photo: Intake photographs of Shizuo Kai, 31, an incarceree transferred to Tule Lake from Jerome along with his wife, Kimi Kai. September 2, 1943. Willard E. Schmidt Papers, Courtesy of San Jose State University Library Special Collections and Archives.

To learn more about this complex topic, Densho recommends the following resources:

Densho Blog

10 Things You Probably Didn’t Know About the “Loyalty Questionnaire”

Memoirs

Starting From Loomis and Other Stories by Hiroshi Kashiwagi

Beyond Loyalty: The Story of a Kibei by Minoru Kiyota

Films

Rabbit in the Moon

Resistance at Tule Lake

Densho Encyclopedia Entries

Loyalty Questionnaire

Questions 27 and 28

Segregation

Tule Lake

Japanese American Citizens League

JACL Apology to Draft Resisters

Pacific Citizen

Lim Report

Non-Fiction Books

Collins, Donald E. Native American Aliens: Disloyalty and the Renunciation of Citizenship by Japanese Americans During World War II. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1985.

Hayashi, Brian Masaru. Democratizing the Enemy: The Japanese American Internment. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Lyon, Cherstin. Prisons and Patriots: Japanese American Wartime Citizenship, Civil Disobedience, and Historical Memory. Temple University Press, 2011.

Muller, Eric. American Inquisition: The Hunt for Japanese American Disloyalty in World War II. University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Takei, Barbara, and Judy Tachibana. Tule Lake Revisited, Second Edition. San Francisco: Tule Lake Committee, 2012.

Weglyn, Michi. Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps. New York: William Morrow & Co., 1976. Updated edition, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996.